Women in the Spanish Civil War

| Part of a series on |

| Women in the Spanish Civil War |

|---|

|

|

|

Women in the Spanish Civil War saw the conflict start on 17 July 1936. The war would impact women's everyday lives. Feminist solutions to problems of women in this period often took an individualistic approach. For women of the Second Republic, by close of the Civil War their efforts for liberation would fail.

While various parties were working to encourage women to their ranks, it was often about reinforcing their own membership numbers and women would be locked out of opportunities for advancement and women's concerns would continue to be ignored on both the Nationalist and Republican sides.

Unlike previous wars including World War I, women for the first time would be involved in large numbers in combat and in support roles on the front. Republican women had the choice to be actively involved in fighting fascism. The first Spanish Republican woman to die on the battlefield was Lina Odena on 13 September 1936. The May Days of 1937 would see leftist women turn on each other, with a number of women being imprisoned, killed or forced into exile, not at the hand of fascists, but by Stalinist Communists on their own side.

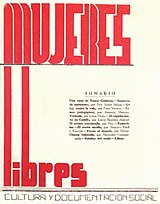

The war ended in 1939, with thirteen women executed as part of a larger group of fifty-six prisoners in Madrid on 5 August 1939 because of their membership of United Socialist Youth. The war also saw the folding of Mujeres Libres, the anarchist women's organisation (1936-1939), and women facing horrible conditions in prison.

Start of the Civil War

On 17 July 1936, the Unión Militar Española launched a coup d'état in North Africa and Spain. They believed they would have an easy victory. They failed to predict the people's attachment to the Second Republic. With the Republic largely maintaining control over its Navy, Franco and others in the military successfully convinced Adolf Hitler to provide transport for Spanish troops from North Africa to the Iberian peninsula. These actions led to a divided Spain, and the protracted events of the Spanish Civil War.[1][2][3][4][5][6] It would not officially end until 1 April 1939.[5][6] Franco's initial coalition included monarchists, conservative Republicans, Falange Española members, Carlist traditionalist, Roman Catholic clergy and the Spanish army.[7][1][8] They had support from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.[7][5] The Republican side included Socialists, Communists, and various other left wing actors.[7][3][5]

The military revolt was announced on the radio across the country, and people took to the streets immediately as they tried to determine the extent of the situation, and if it was a military or political conflict. Dolores Ibárruri would coin the phrase "¡No pasarán!" a few days later, on 18 July 1936 in Madrid while broadcasting on the Ministry of the Interior's radio station, saying, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. ¡No pasarán!"[9]

At the start of the Civil War, there were two primary anarchist organizations: Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Representing working-class people, they set out to prevent the Nationalists from seizing control while also serving as reforming influences inside Spain.[4]

Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union signed the Non-Intervention Treaty in August 1936, promising not to provide material support for the war to any of the parties, even as Germany and Italy were already and continued to provide support to Spain's fascists.[10][9]

Overview

During the Civil War, the problems of everyday life for women changed at times. In major cities like Madrid and Barcelona, women were subjected to much less street harassment.[11] When serving out near the front, men and women could share the same men bed without women having to fear being molested. Women had gone from being objects of men's attention to being viewed as fellow human beings.[11] By the final stretch of the war, women were having to do the jobs of men in many cases as there were not enough men around to do them.[12][13][5] Their presence and the need of their presence often induced anxiety among men, who felt threatened by their presence in factories.[13] As a result of the start of the Civil War, many women's organizations on both the right and the left were shutting down.[14]

In the Civil War period, mainstream leftist feminism often took on an individualistic approach to addressing inequalities.[15] There were also often battles over this issue, whether the personal should be political and vice versa.[15] A few groups challenged the mainstream feminism of the period, including Mujeres Libres.[15] While deliberately rejecting the label of feminism, the group's version of feminism was about creating leadership structures that incorporated everyone, instead of having a feminist leadership model that paralleled patriarchal ones.[15] Many feminists disliked the organization though, as it was affiliated with CNT, where women were often locked out of leadership positions and instead encouraged into their women's auxiliary organization.[15] Others disliked Mujeres Libres decision to downplay the role of specific female leaders, and instead make all feminist actions appear the sole result of collectivist action.[15]

Women's liberation failed on the Republican side by the close of the Civil War. The lack of implementing full liberation during the peaceful period of the Second Republic was a leading cause, as sexist thinking that existed on that side had continued to exist and only found itself being further reinforced as the war progressed.[1]

The Spanish Civil War served to break traditional gender roles on the Republican side. It allowed women to fight openly on the battlefield, a rare occurrence in twentieth century European warfare.[1][16] The war also served to remove the influence of the Catholic Church in defining gender roles on the Republican side.[1] While the war broke down gender norms, it did not create an equitable employment change or remove the domestic tasks as the primary role of women. Behind the scenes, away from the front, women serving in personal family and Republican opposition support roles were still expected to cook for soldiers, launder their uniforms, look after children and tend to dwellings.[11] Women supporting CNT militants found themselves at once liberated from these gender roles, but still expected to serve male fighters in traditional roles.[11]

Role in the family

Mothers had a variety of different experiences during the Civil War depending on their personal situations. Many mothers in rural areas were apolitical, no matter what side of the front they lived on. They had little access to resources that would have allowed them to be politically engaged, and were often short on resources required for basic living.[17]

During the war, mothers worked hard to try to maintain a sense of normalcy. This included continuing domestic education, both among Republican and Nationalist women. Topics of focus included understanding water, agriculture and religious education. Spanish sayings used by mothers at this time included, "After you eat, do not read a single letter." Reading was not viewed as good for digestion. Children were also encouraged by their mothers in rural areas to take a siesta after a meal.[17] During the war, many mothers went to great lengths to try to feed their children during periods of food shortages. They might sneak into other towns to try to get food rations when the ration in their town was too small. They might forgo eating themselves so their children could have bigger portions.[17]

For many mothers in rural areas, the idea of being politically engaged was not possible. They had too many things they had to do at home to have time for that. They had to make soap. They had to work in the fields because of national rationing. Most Spanish homes during the war lacked running water at home. Mothers had to acquire water from local wells, lakes or rivers. They had to wash clothing for the whole family, making a journey to a body of water to do that. They also had to be home to prepare food when it was available. Most homes at this time did not have modern kitchens, and mothers had to cook over open flames using hay and wood for heat.[17]

The war upset the social structure inside the family. Because of survival issues related to food and fear of political persecution, the skills of mother in acquiring and preparing food while also remaining politically invisible meant they began to take on the role of head of household. Silence became a virtue, because doing or saying the wrong thing could lead to death at the hands of Nationalist forces. Women were less likely to be harassed than men, which meant they were often more out of the home. This could create tensions behind closed doors, as it attacked traditional Spanish definitions of masculinity as it made the home the domain of the mother. This change of women being the boss of the home would continue after the Civil War for both Republican and Nationalist families.[17]

The repressive nature of the Civil War and women needing to take charge of the family in rural Spain led to feelings of solidarity among women, and specifically mothers, in pueblos. It led to mothers creating a form of female specific identity that had largely not existed in rural Spain prior to the war.[17]

Political parties and political activity

During the Spanish Civil War, various political and government forces on the Republican side tried to encourage women's participation on their side.[1] Only one group though would be overtly about feminist goals. That group was Mujeres Libres.[19] For the rest of the political parties, labor groups and government organizations, women's rights and feminists goals were not one of their top concerns.[19]

Working-class girls involved with both anarchists and socialists often found themselves ostracizing women from other villages who came from different left wing political parties. There was a lack of solidarity. Pilar Vivancos claimed this was a result of a lack of education among women, with patriarchy within parties being used to set women against each other instead of collectively workings towards emancipation of women. They did not understand what it truly meant, and it made them vulnerable to political puritanism that would later sweep through the left.[11]

Women continued to be locked out of political activity on the Republican side. Meetings for women's rights among union members might be only be attended by men, as the idea of allowing women to attend political events was often alien.[20]

Anarchists

During the Civil War, there were often tensions between the Mujeres Libres and other anarchist groups. The Economic Council of the Socialized Woodwork Industry and Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista both had women in high level leadership positions, and in leadership spots further down. In contrast, Mujeres Libres was a CNT auxiliary, and the women were often denied a specific spot at the table as there was a view among anarchist leaders that the adults, not women, should be the ones making decisions.[21] Anarchists often were unwilling to give solidarity to women combating gender based problems at this time.[21] There were always questions of if women should be fully integrated or should work in women's only groups to achieve specific aims. This resulted in making the movement less effective in accomplishing goals related to women.[21]

Most of the militias that were created during the immediate outbreak of the Civil War came from civil society groups like trade unions and political parties. CNT, UGT and other unions stepped in to provide logistical support for many of these militias.[14] The number of women mobilized was never high. Most joined in order to further support political ideologies they supported. Most came from militant libertarian organizations like CNT, FAI and FIJL. These militias often lacked the typical military structure in order to better represent their ideologies and better mobilize local populations.[14]

Anti-fascists

Anti-fascist organizations often attracted a heterogeneous membership. This at times could lead to major differences, discrepancies and priorities when it came to implementing anti-fascist programs.[16] Different groups including socialists, communists and anarchists would sometimes work to take advantage of this inside these organizations.[16]

Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas

While the Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas (AMA) represented women from a wide variety of political backgrounds, it ended up serving as a vehicle of communist orthodoxy designed to mobilise women to support the Communist cause on the Republican side of the civil war.[16]

Communists

The varying political parties during this period on the left would all work with each other and, in the latter stages of the war, against each other. The PCE would often be at the center of much of this, trying to attract support for their Stalinist Communism ideology from various left-wing factions. When they were not trying to directly collaborate, crossover in membership would see many communist women involved in other organizations.[22][23][16][24]

Female Stalinists actively participated in POUM and Trotskyite purges in Barcelona. Women like Teresa Pàmies were intentionally excluded by POUM affiliated women even as they tried to build bridges with PSOE.[25][26] Pàmies wrote for a number of Communist publications during the war while she was only a teenager. These publications included Juliol, Treball, and La Rambla.[25] During the Civil War, Pàmies founded the Catalan branch of JSU. Near the end of the war, she was a delegate at the Second World Youth Peace Conference at Vassar College in the United States. While there, she was surrounded by all the Spanish leftist factions, except POUM.[25] Pàmies would also be responsible for isolating POUM's youth organization, Juventudes Comunistas Ibéricas, in such a way that it would leave blood on her hands.[25] Teresa Pàmies exclusion of POUM is notable as her cousins were part of the organization, and her opinion of them was that they were committed anti-Fascists.[25]

Partido Comunista de España

While other communist organizations existed, Partido Comunista de España remained the dominant one.[27][3] In the first year of the Civil War, the PCE rapidly increased their membership by nearly three-fold. Among the peasantry, women represented nearly a third of PCE's membership.[28]

During the Civil War, Dolores Ibárruri continued to travel the country to speak in opposition to Francoist forces. She also used radio to spread her message, becoming famous for calling men and women to arms. The Communist Party did not approve of her private life though, asking her to end her relationship with a male party member who was seventeen years younger than her, which she did.[29]

Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM)

Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) was the dissident communist party during this period. Their engagement for women involved trying to create specific female sub-organizations for them to join.[16] POUM women served on the front, but were also engaged in many other important roles including in POUM governance, writing and publishing POUM affiliated publications, and serving as teachers among the civilian population.[23]

Republican women supporters abroad

Much of the aid work on the Republican side by women supporters abroad was done by working-class women. In Scotland, they often utilized strollers and prams to collect donations. Working-class women were also heavily involved in organizing fundraisers in Scotland on behalf of Republicans. These were some of the few positions easily available to them, as they were and continued to be locked out of more overt political and union activity during the war.[30]

Nationalists and Catholics

Falangist women activists were often divided into groups, which were largely based on age. Younger activists were often outside the home, working on Nationalist goals in Nationalist women's organizations. Older women Nationalist activists believed they should be outside the public eye, serving Nationalist interests by working in the home.[31] Nationalist women in more rural, less cosmopolitan cities, often had more privileges than their urban counterparts. They were able to leave the house, regardless of their marital status, and engage in the everyday tasks required for living. Few people noticed and cared.[13] While Nationalist forces believed women should be at home, the realities of war meant that women were required to work outside the home, in factories and other businesses.[31] During the war, Nationalist publications encouraged women to stay at home in service of the family. They were discouraged from shopping, going to the movies and engaging in other behavior viewed as frivolous by Nationalist male leaders.[32]

Nationalist supporting women behind Nationalist lines also sometimes were involved in auxiliary roles. This included working as nurses, provisioners and support personnel.[33][32] They were encouraged to do so by men as a means of supporting the traditional Spanish family structure.[32]

Many Spanish women during the war sided with the Nationalists, embracing the strict gender roles put forth by the Catholic Church. The sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera worked to mobilize these women in Sección Femenina, an umbrella organization of Falange, during the pre-Civil War period and later during the war. From 300 members in 1934, its membership swelled to 400,000 in 1938. Women involved with the organization often went on to work for Auxilio Social, which acted as a social assistance organization for widows, orphans and the destitute by providing them with food and clothing. In all these roles, Spanish Nationalist women never did so with the intention of challenging male authority; they wanted to see the continuance of Republican gender roles and to strengthen the Spanish family.[29][2][19]

Starting in October 1937, Sección Femenina de la Falange Española started actively recruiting single women between the ages of 17 and 35 to do social work as a volunteer for six months.[31][32][19] In some cases, service was mandatory. It represented the first mass mobilization of women by Nationalist forces.[32][19]

Auxilio Social became the largest Nationalist social aid organization during the civil war. It was modeled after Nazi Germany's Winter Aid program. Staffed by women wearing blue uniforms with white aprons, they worked in taking care of children and other displaced people, and in distributing aid. The purpose of women in this organization was to serve others in maintaining traditional Spanish families within a patriarchal state.[31][34]

Nationalist women had another organization for which they could volunteer, the Margaritas, and came from traditionalist Carlist philosophies. Their purpose was to support Spanish families, with a husband in charge of a pious and religious wife and obedient children.[31][34]

Pilar Jaraiz Franco, the niece of Francisco Franco, sympathized with her uncle's politics and, during the Civil War, spent some time in a Republican prison. Despite this, she gradually moved towards more socialist leanings as a result of the rigid gender norms forced on her during her childhood.[35]

Salamanca and Burgos became home to large numbers of women who were wives of military officers on the Nationalist side. They could largely live comfortable, as their part of Spain was not in a state of total war. Both cities had zones for homes, and military zones. The military zones were home to medical services and to prostitutes. Nationalist nurses working in these zones were viewed as essential but transgressive, as they were occupying male spaces. As such, their behavior was always highly watched.[13] Poverty and economic need often pushed many women into prostitution, where it flourished behind Nationalist lines. That Nationalist forces were fighting for a Spain that supported traditional family structures and opposed to prostitution did nothing to stop Nationalist officers from using prostitutes.[32]

Despite nationalist ideals about the role of women, the Nationalist attracted single women from abroad to their cause. These women, by their mere existence, transgressed Nationalist teachings about women as they were traveling alone, accompanied by male guardians, and acting on their own behalf. Many were literate and well traveled. Many came from European aristocratic and were upper class. Full of self-confidence, they made Nationalists uncomfortable, especially in contrast to the typically poor, illiterate Spanish woman who had not traveled. Their advocacy on behalf of Franco was viewed by many as counter-productive as it suggested women could find success outside the home, when Francoists and Nationalists believed women belonged in the home.[13]

Nationalist forces did attract foreign women writers and photographers to their cause. These included Helen Nicholson, the Baroness de Zglinitzki, Aileen O'Brien, Jane Anderson, Pip Scott-Ellis, and Florence Farmborough.[13][36] These women were all advocates of right wing-ideology, and militantly opposed to Communism. They came from a wide variety of right wing ideologies, including monarchists and fascism.[13]

Civilian women on the home front

Many poor, illiterate and unemployed women often found themselves immersed in the ideological battle of the Civil War and its connected violence as a result of forces beyond their control. Some of these women chose to try to reassert control by becoming active participants in the violent struggle going on around them.[7][12] When it came to deciding who was right and wrong, many women had to use their own moral judgement formed by a lifetime to do so. They were not guided by political radicalization leading to ideological based morality.[12]

Women and children behind the lines were used by all sides, as a way of trying to garner support for their sides in the Civil War both internally and internationally.[36][37] Nationalists often appealed to Catholics overseas, condemning Republican bombings on women in civil populations, claiming over 300,000 women and children had been killed. This met with limited success in the United States, where Catholics were uneasy with bombings against women and children that were being committed by both sides.[36]

One tactic employed by Nationalist troops was to use women to try to lure out Republican forces from concealed positions. They would use women's voices or get women to say they were civilians under siege. As a consequence, some Republican troops were hesitant when confronting women under apparent siege on the front as they did not always trust claims of needs for assistance.[38]

Spanish women supported the Republican war efforts behind the front lines. They made uniforms, worked in munitions factors, and served in women's corps similar to those organized by the US and British during World War I.[39] In Madrid, women would go in pairs to cafes around the city, collecting money to support in the war effort.[39] Many women on the Republican side joined JSU, serving in civilian roles near the front.[40]

Behind Nationalist lines, all women were forbidden from wearing trousers. Instead, women were to wear skirts, which had to be long. Shirts were required to be long sleeved.[20] Rape was so common that many pregnant women did not know who the fathers of their children were.[41] Rape, along with murder and torture, were frequent tools used by Nationalist forces to instill terror in women and keep them in line.[37]

Women in combat and on the front

Because of changes in society, women who wanted to be involved in the fight against fascist forces had two options: they could fight on the front lines or they could serve in auxiliary roles away from the front. Their options were not limited, like that of many women near the battlefields of World War I, where the only available role was that of auxiliary role to support men on the front.[1][16]

While women had been sporadically involved in combat in Spain, no large organized force of female fighters (Template:Lang-es) had been mobilized prior to the Civil War.[1][24][10] Notable women who had participated in the past included Napoleon resistance fighter Agustina de Aragón, Manuela Malasaña and Clara del Rey during the Peninsular War and Aida Lafuente, who took part in militant labor action in October 1934 in Asturias.[1] During the Peninsular War, a writer for the La Gaceta de Madrid would ask why the city's women fighters exceeded their men in courage.[42] Despite their status as national icons, these women were the exception to the rule about women's roles in war.[1][42]

Nationalist women behind Republican lines

Many Nationalist sympathizing women were killed behind Republican lines. Around 8,000 priests and nuns were tortured or murdered behind Republican lines.[43] These deaths were part of the over 89,000 executions historians believed were conducted by Republican forces in the lead up to and during the Spanish Civil War.[43]

Death sentences and life in prison

Republican women in prisons often faced situations their male counterparts did not have to deal with.[44] Unlike their male counterparts, many women given death sentences for military rebellion were given the status of common criminals.[44] Some women in Nationalist zones found their husbands arrested and executed because a Nationalist soldier coveted her.[44][41] Children were removed from their mothers, left in the care of family or to live on the streets. Some women with sons who fought for the Republic were forced to watch them be tortured or executed.[44][41] Prior to going to prison, some women were raped by male police officers. Some women were removed from prison at night by Falangists who would then rape them. During these nights away from prison by Falangist forces, some women were also branded with a yoke and arrows.[44] Borrowing from a practice being used by Mussolini's forces in Italy, women in prison were often forced to drink castor oil with the intention of giving them diarrhea. The purpose was to humiliate these women when they soiled themselves.[37] Women in prison often had a toilet ratio of one toilet for every 200 women.[44] By the end of the Civil War, the Las Ventas Model Prison had swelled from 500 female prisoners to over 11,000.[45]

1936

The Moorish troops of General Gonzalo Queipo de Llana were promised the opportunity by the General to rape Republican women. It was not unusual, and turned into a standard practice for captured women to be turned over to these men for abuse as a way of terrifying local populations.[20][41] 20 women believed to be Republican sympathizers were removed from a maternity ward in Toledo and executed. The Nationalist soldiers then threw their bodies down a nearby well, and proceeded to parade through a local village with the dead women's underwear draped on their rifles.[20]

Women were often highly involved with their local agricultural collectives during the war. When the local government tried to confiscate milk from Peñalba, Huesca, women farmers were some of the most vocal in protesting the action.[46]

July 1936

In the fight against fascism, the militia woman (Template:Lang-es) served as an important figure for Republican forces in the period between July and December 1936.[5][1][7][2]

August 1936

Asociación de Mujeres contra la Guerra y el Fascismo underwent a second name change in 1936, shortly after the start of the Civil War. Their new name was Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas. From there, the group would play a prominent role in sending and supporting women on the front lines in the war.[14]

In August 1936, the Commission of Women's Aid in Madrid was created following a decree by the Republican Prime Minister.[16]

Lina Odena, Casilda Méndez, Aída Lafuente, Rosario Sánchez Mora, Concha Lozano, and Maruja Tomicoson were all milicianas who would be immortalized by the Republic during this period of active women's involvement in combat.[47] POUM initially required both men and women in combat to also engage in support roles as needed. Women were in the trenches and stood guard. Captain Fernando Saavedra of the Sargento Vázquez Battalion said these women fought just like men.[24]

Fidela Fernández de Velasco Pérez had been trained in the use of arms before the start of the war, and served on the front lines right away outside Madrid. She captured a cannon from Fascist forces, before being transferred to the Toledo front. Her new unit was the same one which Rosario Sánchez de la Mora was serving. There, Fernández de Velasco Pérez fought on the front and sought action by going behind enemy lines to sabotage them alongside other shock troops. She learned how to construct bombs.[24]

When the war broke out, Margarita Ribalta was initially assigned by JSU to a position at headquarters. Unhappy with not being more involved, a few days later she enrolled with a Partido Comunista de España column and was transferred to the front, where she volunteered to be part of an advance group trying to take a hill. She led her group, running between two Nationalist positions while carrying a machine gun. A Republican support plane mistook her group for fascists, bombing them and wounding Ribalta.[24]

In the first days of the war, Trinidad Revolto Cervello was involved in front line combat at the Military Headquarters and at the Atarazanas Barracks in Barcelona. Following that action, she joined Popular Militias and went to the Balaeric Islands, where she again saw front line action at Battle of Mallorca.[24]

Teófila Madroñal was another Spanish woman who served on the front lines. She enlisted in Leningrad Battalion during the first days of the war, underwent weapons training and then was deployed to the Estremadura highway during the Siege of Madrid.[24]

When Constantina was taken by Nationalist forces on 7 August 1936, those forces sought revenge for anarchist shooting of Nationalist prisoners. Women who had found themselves widowed recently or who had husbands serving with the Republican side were raped in a mass orgy event fueled by alcohol provided by local wineries. On 10 August, show trials were held and many women were given death sentences for things like displaying Republican flags, expressing admiration for President Roosevelt or criticizing their employers. Among the women executed were two pregnant girls.[44]

In Lora, where Nationalist forces killed between six hundred and one thousand people in the summer of 1936, women who survived often had their heads shaved to where just a tuft remained, and that tuft then had a ribbon with monarchist colors tied to it. These women were also often subject to abuse and further humiliation.[44]

The start of the Civil War saw women in Barcelona change their behavior, notably in the way they dressed. For the first time, they were able to appear in public wearing pants without people perceiving them as violating societal norms about decency.[39] Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia began to dominate on the socialist side in Catalonia late 1936, and finally consolidated power in 1937 on the Republican side.[16]

While other communist organizations existed, Partido Comunista de España remained the dominant one.[12][3] In the first year of the Civil War, the Partido Comunista de España rapidly increased their membership by nearly three-fold. Among the peasantry, women represented nearly a third of PCE's membership.[28] During the Civil War, Ibárruri earned herself the nickname La Pasionaria as she traveled the country to speak in opposition to Francoist forces. She also used radio to spread her message, becoming famous for calling men and women to arms, saying, "¡No pasarán!". One of the most famous phrases she uttered in the civil war was "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees". The Communist Party did not approve of her private life though, asking her to end her relationship with a male party member who was seventeen years younger than her, which she did.[29] Female Stalinists actively participated in POUM and Trotskyite purges in Barcelona. Women like Teresa Pàmies intentionally excluded POUM affiliated women even as they tried to build bridges with PCE.[25]

September 1936

The first Spanish Republican women to die on the battlefield was Lina Odena on 13 September 1936. With Nationalist forces overrunning her position, the unit commander chose to commit suicide rather than to surrender.[7][24][29] Her death would be widely shared by both Republican and Falangist propagandists. With Nationalist forces threatening her with the potential of being raped by Moorish soldiers if she does not surrender, Republicans were able to cast her as an innocent who chose death rather than to be debased and lose her honor. Falangist propaganda said there was never there and there was never a threat of rape. This made Odena's death meaningless. Beyond that, Falangist propaganda implied Odena had been guilty of murdering a Catholic priest a few weeks prior, with her suicide was a way of escaping punishment.[7]

In September 1936, the Largo Caballero Battalion which included about ten women, fought on the Sierra front. Those in combat included Josefina Vara.[24]

There are conflicting accounts by historians as to when the decision was made to remove women from the front on the Republican side. One side dates the decision to late fall of 1936 as the date when Prime Minister Francisco Largo Caballero gave the order. Others date the order to March 1937. What is most likely is that various political and military leaders made their own decisions based on their own beliefs that led to different groups of female combatants gradually being withdrawn from the front.[21][1][33][11][48][10] But whatever date ascribed, women were being encouraged to leave the front by September 1936.[10]

October 1936

The International Group of the Durruti Column had many women serving in it. Involved in fighting in October 1936 at Perdiguera, a group of these women died. The dead included Suzanna Girbe, Augusta Marx, Juliette Baudard, Eugenie Casteu and Georgette Kokoczinski. The next month, Suzanna Hans of the same group died at the battle of Farlete.[24]

Women militants and civilians were part of the group that found themselves trapped for four days at the Sigüenza Cathedral as a result of a Nationalist siege in October 1936. After running out of food and ammo, with the walls of the Cathedral beginning to fall from incessant cannon fire, many in the group decided to make a run for it at night. POUM Captain Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère was among those at the cathedral. She was one of the approximately one third of people who fled who survived. Her bravery during the Siege of Sigüenza earned her a promotion to POUM's Lenin Battalion Second Company Captain. After recovering from the siege in Barcelona, she was ordered to Moncloa, where she was in charge of a special shock troop brigade.[24]

Pregnancy and nursing babies could not save women from death. In Zamora, death by firing squad was common for these women. Amparo Barayón, who was still nursing, had her eight-month-old daughter removed from her arms and put into a Catholic orphanage on 11 October 1936. The following day, she was executed.[44] Pregnant women with death sentences sometimes had their executions stayed long enough so that they could give birth, with their babies then being stolen by Nationalist sympathizers.[41][44]

November 1936

Many Spaniards headed to Gibraltar to try to seek refuge from the war. The British were largely unwilling to deal with this as most did not want to return to Spain. Still, the British evacuated most Spaniards in Gibraltar to Málaga. On 22 November 1936, they evacuated 157 on HMS Griffin of which 54 were women and 82 were children. On 27 December 1936, 185 were evacuated on HMS Gipsy including 16 women and 26 children. On 3 January 1937, 252 people were evacuated on HMS Gallant including 67 women and 49 children. On 13 January 1937, 212 were evacuated by HMS Achates of which were 36 were women and 22 were children. Another 536 people were on three other ships where total numbers of women were not recorded.[49]

Women in rearguard battalions often met daily to practice weapons training, marching and drilling. Many also received specialized training in the use of machine guns.[24] Union de Muchachas was a communist organized rearguard women's only battalion in Madrid that fought on the front line starting on 8 November 1936. The battalion included two thousand women aged fourteen to twenty-five who had been training since July 1936, when the Civil War began. Positioned at Segovia Bridge and near Getafe on the Carabanchel front and representing the bulk of the Republican forces in those positions, Union de Muchachas fighters were among the last to retreat.[24]

Women's only battalions existed behind the front lines as rearguard support in defense of their cities. Barcelona had such a battalion organized by PSUC. In Mallorca, there was the Rosa Luxemburg Battalion that saw action on the front in defense of the city. Madrid had the Union de Muchachas which served on the front in November 1936 in the Battle for Madrid.[24]

Art continued during the Civil War. María Zambrano was one of several editors, the only woman, of the art magazine, Hora de España. They moved their base to Valencia in 1936, following the Republican government from Madrid there as they believed it was important to continue Spain's intellectual period even during the war. When Valencia fell, Zambrano moved with the group to Barcelona in the fall of 1938 where she helped published the magazine's final edition in 1939. Its final edition that year was limited as the printing press was destroyed mid-run.[33]

December 1936

In the last half of 1936, milicianas were not considered exceptional; they served as comrades alongside men in separate or mixed gender battalions.[1][16] This was in large part because many of the milicianas were motivated to fight because their own revolutionary beliefs: they believed their involvement could change the course of the war, and bring about a new revolution in thinking in society.[1][21] A few women fought because they were following husbands, fathers or sons into battle. This group though represented a very small minority, with the majority fighting for ideological reasons.[1] While the national branches of Communist Party supported sending foreign fighters to Spain to fight in the Civil War in the International Brigades, they often opposed their female members from going. When they sometimes agreed to send determined women to Spain, it was often in support roles as reporters or propagandists. The party apparatus in Spain then actively worked to keep women away from the front.[29]

On 25 December 1936, the Generalitat de Cataluña made abortion legal for the first time in the history of Spain following a decree from the Health Department. The anarchist-dominated Health Department then followed this up in March 1937 with regulations for hospitals and clinics about how to conduct abortions. The same government also for the first time provided government sponsored information and access to birth control, coupling it with information and treatment for venereal disease.[11][1]

During the Civil War, broader problems that pre-dated it continued for PSOE, with socialist groups tending to lack female participation in the early months of the war. When socialist women wanted to get involved, they either had to do so through socialist youth organizations or they had to switch allegiances to the communist, who were more accepting of women and more likely to put them into leadership positions.[24]

During the winter of 1936, the Republican government tried to formally convert militias into units in their armed forces. Until this point, women had joined militias affiliated with various political parties and unions.[47]

1937

Women also came from abroad to fight as part of the International Brigades, with their total numbers documented at between 400 and 700 women. Many women first traveled to Paris, before going by boat or train to fight. A 1937 agreement designed to stop foreign intervention eventually largely put a stop to recruitment to the International Brigades for both men and women.[14]

The Women's Aid Committee was formed during the Civil War at the direction of the Minister of Defense. It was largely staffed by members of the Women Against War. Their activities included mobilizing women into large protest. One such protest demanded that men deemed non-essential by the government were sent to the front, with women taking their places in the workforce. The organization held its first national conference in 1937 in Valencia, drawing women from across Spain who represented all classes and leftist ideologies.[9]

The Nationalists using rape by Berber forces as a way of bringing women and children into compliance was so problematic, that the British who were scared of allowing Republican refugees in lest they spread the contagion of Communism in the country, finally allowed 3,889 Basque children and 219 female Basque teaches in 1937 to board Habana and Goizeko Izarra and head to Britain. The British Government feared being made complicit in rape.[37]

January 1937

In January 1937 at the Battle of Jarama, Republican forces were near the point of retreating until three Spanish milicianas inspired the men they were serving with to hold fast. The women, manning a machine gun post, refused to retreat.[24]

March 1937

Socialist women were more active abroad than at home in their opposition to the Spanish Civil War. Belgian women socialists were opposed to their socialist party's neutrality during the Spanish Civil War. To counter this, these women socialist were active in trying to evacuate refugees. Among their accomplishments were evacuating 450 Basque children to Belgium in March 1937. With the assistance of the Belgian Red Cross and Communist's Red Aid, socialist women organized the placement of 4,000 Spanish refugees.[50]

Both foreign and domestic media printed images of these female fighters on Spain's front lines as boldly breaking gender norms. Initially, they presented problems for some people in Spain, as the country had very traditional ideas about gender roles. While Republicans became more accepting of them, this started to change yet again by December 1936 when the Government of the Second Republic started using the slogan, "Men to the Front, Women to the Home Front." By March 1937, this attitude had spread to the front lines, where militia women, over their own objections, were withdrawn or placed into secondary roles.[2][1]

Women were told to leave the front in Guadalajara in March 1937.[11] Following the battle, many were loaded into cars and taken to support positions further behind the lines. A few refused to leave, and their fate is uncertain though friends suspected most died in combat.[11] Expelled soldiers included Leopoldine Kokes of the International Group of the Durruti Column.[24] Some demobilized women left the front, and joined women's columns on the home front, in defense of cities like Madrid and Barcelona.[10] When Juan Negrín became the head of the Republican armed forces in May 1937, women's time in combat ended as he continued efforts to regularize Republican forces.[47]

Following their removal from the front, milicianas and women in general stopped featuring in Republican propaganda. Visually, they returned to their lives before the war, where their primary role was behind the scenes at home.[13][24] Communists and anarchists columns attracted the most women among all the political groups on the Republican front. Stories about POUM militants became more well known as they were more likely to have published their memories or had better contacts with international media.[24]

May 1937

During the Second Republic and during the initial stages of the Civil War, there was a social and economic revolution in women's rights, especially in areas like Catalonia. Because of the nature of war, many reforms were sporadically and inconsistently implemented, and advances made during the latter half of 1936 were largely erased by May 1937.[1]

From February to May 1937, there were many protests led by women over the subsistence living created as a result of high food prices and bread shortages that came into great effect following the sixth anniversary of the Republic.[40]

Working-class women in Barcelona would often queue for hours for bread in 1937, only to find none was available. This sometimes would lead to rioting, which CNT leadership then worked hard to fault each other over in an attempt to avoid responsibility for the bread shortage. The problem was compounded by the fact that middle and upper-class people in Barcelona were readily buying bread on the black market.[21][46]

One riot occurred on 6 May 1937, when women looted vans full of oranges at the Barcelona port.[46] When this aspect was brought to attention, CNT offered sexist excuses as to why working-class women were unable to buy bread. The result was that ordinary working-class women in the city often turned on anarchist women, and blaming them despite the anarchist women not being involved in CNT leadership.[21] Mujeres Libres, CNT's women's arm, addressed this problem by taking action into their own hands, and staging assaults on markets to provide food for other women. Food riots would become a common feature in Barcelona during the Civil War.[21]

One of the few publicly socialist identified women in this period was María Elisa García, who served as a miliciana with the Popular Militias as a member Asturias Battalion Somoza company. She fought with the Battalion at the Lugones front, and later in the Basque mountains. She was killed in combat in the mountains of Múgica on 9 May 1937.[24]

May Days of 1937

In the lead up to the May Days events, Communists aligned with the Soviet Union had largely taken control of the ports, where most of the support materials and relief aid coming in for distribution around the country were from the Soviet Union. They soon became a de facto police force, and were already working to undermine anarchists.[51][52][53] 1 May 1937 saw thousands of armed anarchists take to the streets, daring the government and police to disarm them. Open conflict started on 3 May 1937 in front of the Telefónica building. On 4 May 1937, the city had come to a complete work stoppage, with machine guns appearing in placements along the major streets in the city.[54][55][56] By the conclusion of major fighting on 8 May 1937, over 1,000 people would be dead and another 1,5000 were wounded.[57] POUM leadership would see this all come to a tragic head on 16 June 1937 when Andrés Nin and the POUM executive were arrested. The next day, foreign POUM members and supporters were arrested en masse at the Hotel Falcon and taken to prison.[54][55][56] Eventually, many foreign supporters of POUM in the group would be rescued in part because of the actions of the journalist George Tioli. The US Consulate, informed of the imprisonment thanks to Tioli, worked to secure the release of a number of them.[54][55][56]

The remnants of the POUM leadership were put on trial in Barcelona on 11 October 1938.[58][59] Ibárruri was quoted as saying of their arraignment, "If there is an adage which says that in normal times it is preferable to acquit a hundred guilty ones than to punish a single innocent one, when the life of a people is in danger it is better to convict a hundred innocent ones than to acquit a single guilty one."[60]

June 1937

Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) was the dissident communist party during this period. Their engagement with women involved trying to create specific female sub-organizations for them to join.[16] In June 1937, the Franco regime and the Communists in control of Republican areas both declared POUM illegal, leading to the dissolution of the group.[23]

Unión Democrática de Cataluña (UDC) saw a communist hegemony emerge by late 1937. They moved more away from their center right policies of their founding, and more towards positions supported by PSUC.[16]

In the Republican offensive against Nationalist held Teruel from December 1937 to February 1938, brigades on the ground tried to honor Indalecio Prieto's call to protect civilians, and particularly women in children. They sometimes stopped shelling buildings when people inside made clear they were non-combatant women and children. The reality of the offensive and life on the front lines meant many of those civilians had nothing. Women would often risk their lives to loot recently shelled buildings. They needed furniture to burn to melt snow for water, to cook and to provide some heat. Many women, on both sides in the city, died of starvation during the month long battle.[61]

August 1937

Martín Veloz led a column of Bloque Agrario, Acción Popular and Falange members on a purge of Republican forces in 1937 in villages in the Salamanca area like El Pedroso, La Orbada, Cantalpino and Villoria. Republican men were shot, while Republican women were raped, and then had their heads shaved before being paraded through their villages. The area had not had any major uprising prior to this by Republican forces.[44]

Martín Veloz was part of a group that on 24 August 1937 that murdered twenty-two men and one woman in Cantalpino. Following this, the group then raped many women, and shaved the heads of around one hundred women before making them parade through the streets.[44]

September 1937

Foreign observers covering the war often wrote about women's bravery on the front, including saying they took enemy fire better than many of the men they fought alongside. One example of such bravery happened in Cerro Muriano in September 1937, where Republican army forces from Jaén and Valencia fled the front while the small militia force from Alcoy, which included two women, withstood a Nationalist bombardment.[24]

October 1937

Argentina García was on the front in October 1937 in San Esteban de las Cruces. The communist's bravery in battle was recognized with a promotion to captain in her Astruias Battalion.[24]

1938

Mujeres Libres became one of the most important women's anarchist organizations during the Civil War.[1][20] Their Civil War ranks were aided by women moving over from CNT to participation in their organization.[15] The organization's importance was a result of the activities they were carrying out which included running educational programming, and trying to increase the literacy rate among women. They were also organizing collective kitchens, parent controlled daycare centers, and providing prenatal and infant health information to expecting parents.[1][20] Mujeres Libres had over 20,000 members by 1938.[1][15][4] Mujeres Libres was also publishing a journal of the same name in 1938. Writings found in it focused on personal autonomy, the creation of female identities, and self-esteem.[33][41] It also often addressed the conflicts in identity between being a woman and being a mother, and how women should navigate their identities as maternal figures.[41]

The October 1938 CNT congress in Barcelona saw Mujeres Libres locked out, with the fifteen women strong delegation barred from entering. Women had previously been allowed to attend, but only as representatives of other, mixed gendered anarchist organizations. A women's only organization was not tolerated. The women protested this, and would not get an answer until an extraordinary meeting of CNT on 11 February 1939. When their answer came, it was that "an independent women's organization would undermine the overall strength of the libertarian movement and inject and element of disunity that would have negative consequences for the development of working-class interests and the liberarian movement on the whole."[10]

During the bombing raid of Republican airforce, known also as La Gloriosa, which targeted a small Andalusian town of Cabra, most of some 100-110 fatal casualties were women. It was the most deadly Republican bombing recorded during the war; it proved fatal as most bombs were dropped during a weekly fair. It was later claimed that Republican pilots have mistakenly taken provisional merchandise tents for makeshift premises of the Italian CTV.

Throughout 1938 American anti-communist activist Aileen O'Brien returned to the United States after 17 months in Spain to give a lecture series advocating for the nationalist faction.[62] Nationalist memoirist Luis Bolín recounted that while in the United States, O’Brien spoke on the telephone to every Catholic bishop in the country and begged them to request that their parish priests ask all members of their congregations to telegraph in protest to President Roosevelt.[63] As a result, Bolín claimed, more than a million telegrams were received by the White House and a shipment of arms to the Republicans was stopped.[63]

1939

Pregnant women could be subject to beatings and torture. Some were given electric shocks to their nipples, lower genitalia and ears. For those who survived this, they were often plagued with mental illness and headaches that lasted years.[44] Nursing mothers in prison often had to deal with unsanitary conditions and the presence of rats. In some prisons, like Ventas, water for toilets and sinks was turned off. Ten to fifteen infant corpses a day were often found in the Ventas prison, with children dying from meningitis.[44] Julia Manzanal was arrested in Madrid in early 1939, right after she had given birth. As a result, she was allowed to take her infant daughter with her. The baby lived only ten months before succumbing to meningitis.[44]

Mujeres Libres folded by the end of the Civil War.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Lines, Lisa Margaret (2012). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164921.

- ^ a b c d Jackson, Angela (2003-09-02). British Women and the Spanish Civil War. Routledge. ISBN 9781134471065.

- ^ a b c d Petrou, Michael (2008-03-01). Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774858281.

- ^ a b c d Hastings, Alex (18 March 2016). "Mujeres Libres: Lessons on Anarchism and Feminism from Spain's Free Women". Scholars Week. 1. Western Washington University.

- ^ a b c d e f Martin Moruno, Dolorès (2010). "Becoming visible and real: Images of Republican Women during the Spanish Civil War". Visual Culture & Gender. 5: 5–15.

- ^ a b Bunk, Brian D. (2007-03-28). Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822339434.

- ^ a b c d e f g Linhard, Tabea Alexa (2005). Fearless Women in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826264985.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b c Ibárruri, Dolores (1966). Autobiography of La Pasionaria. International Publishers Co. ISBN 9780717804689.

- ^ a b c d e f de Ayguavives, Mònica (2014). Mujeres Libres: Reclaiming their predecessors, their feminisms and the voice of women in the Spanish Civil War history (Masters Thesis). Budapest, Hungary: Central European University, Department of Gender Studies.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fraser, Ronald (2012-06-30). Blood Of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War. Random House. ISBN 9781448138180.

- ^ a b c d Cuevas, Tomasa (1998). Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791438572.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Basilio, MiriamM (2017-07-05). Visual Propaganda, Exhibitions, and the Spanish Civil War. Routledge. ISBN 9781351537438.

- ^ a b c d e Ávila Espada, Mar (2017). La miliciana en la guerra civil: Realidad e imagen (PDF) (Masters thesis thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad de Sevilla.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. AK Press. ISBN 9781902593968.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nash, Mary (1995). Defying male civilization: women in the Spanish Civil War. Arden Press. ISBN 9780912869155.

- ^ a b c d e f Schmoll, Brett (2014). "Solidarity and silence: motherhood in the Spanish Civil War" (PDF). Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. 15 (4): 475–489. doi:10.1080/14636204.2014.991491. S2CID 143025176.

- ^ published in Gracia y Justicia, conservative magazine of political humor published in Spain during the Second Republic. It shows a woman with her boyfriend, both humble, planning her marriage to a wealthy man (Don Gregorio) only to get his fortune after the divorce. The vignette is part of the campaign organized by Catholic right media and parties in order to avoid the legalization of divorce. The text that accompanies the cartoon reads: "I thought that first I will marry Don Gregorio, and with the money that I will take from him in the divorce, I will marry you and live happily."

- ^ a b c d e Ryan, Lorraine (January 2006). Pelan, Rebecca (ed.). A Case Apart: The Evolution of Spanish Feminism. Galway: National Women Studies Centre.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Hochschild, Adam (2016-03-29). Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547974538.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Evans, Danny (2018-05-08). Revolution and the State: Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Routledge. ISBN 9781351664738.

- ^ Rees, Tim; Thorpe, Andrew (1998). International Communism and the Communist International, 1919-43. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719055461.

- ^ a b c Coignard, Cindy; Simó-Nin i Espinosa, Cristina; Giráldez Puvill, Marta (2017). Las militantes del Poum (in Spanish). Barcelona: Laertes. ISBN 9788416783229. OCLC 1011625404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Lines, Lisa Margaret (May 2009). "Female Combatants in the Spanish Civil War: Milicianas on the Front Lines and in the Rearguard". Journal of International Women's Studies. 11 (4).

- ^ a b c d e f Herrmann, Gina (2010). Written in Red: The Communist Memoir in Spain. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252034695.

- ^ Rees, Tim; Thorpe, Andrew (1998). International Communism and the Communist International, 1919-43. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719055461.

- ^ Cuevas, Tomasa (1998). Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791438572.

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley G. (2008-10-01). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300130782.

- ^ a b c d e Cook, Bernard A. (2006). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097708.

- ^ Gray, Daniel (2013-07-22). Homage to Caledonia: Scotland and the Spanish Civil War. Luath Press Limited. ISBN 9781909912120.

- ^ a b c d e Keene, Judith (2007-04-10). Fighting For Franco: International Volunteers in Nationalist Spain During the Spanish Civil War. A&C Black. ISBN 9781852855932.

- ^ a b c d e f Esenwein, George R. (2005-11-16). The Spanish Civil War: A Modern Tragedy. Routledge. ISBN 9781134629688.

- ^ a b c d Bieder, Maryellen; Johnson, Roberta (2016-12-01). Spanish Women Writers and Spain's Civil War. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134777167.

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ Mangini, Shirley; González, Shirley Mangini (1995). Memories of Resistance: Women's Voices from the Spanish Civil War. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300058161.

- ^ a b c Tierney, Dominic (2007-06-11). FDR and the Spanish Civil War. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822390626.

- ^ a b c d Rhodes, Richard (2015-02-03). Hell and Good Company: The Spanish Civil War and the World it Made. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451696233.

- ^ Nelson, Jubilee Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences Cary; Nelson, Cary; Hendricks, Jefferson (1996). Madrid 1937: Letters of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the Spanish Civil War. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415914086.

- ^ a b c Alpert, Michael (2013-02-28). The Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107328570.

- ^ a b Graham, Helen (2002). The Spanish Republic at War, 1936–1939. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521459327.

- ^ a b c d e f g Memory and Cultural History of the Spanish Civil War: Realms of Oblivion. BRILL. 2013-10-04. ISBN 9789004259966.

- ^ a b "Manuela Malasaña, la doncella que representó la España ultrajada". ABC (in Spanish). 2 December 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b Cuevas, Tomasa (1998). Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791438572.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Preston, Paul (2012-04-16). The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393239669.

- ^ Browne, Sebastian (2018-08-06). Medicine and Conflict: The Spanish Civil War and its Traumatic Legacy. Routledge. ISBN 9781351186490.

- ^ a b c Seidman, Michael (2002-11-23). Republic of Egos: A Social History of the Spanish Civil War. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299178635.

- ^ a b c González Naranjo, Rocío (1 March 2017). "Usar y tirar: las mujeres republicanas en la propaganda de guerra". Los ojos de Hipatia (in European Spanish). Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ Alberca, Julio Ponce (2014-11-20). Gibraltar and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39: Local, National and International Perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472525284.

- ^ Gruber, Helmut; Graves†, Pamela; ontributors (1998-01-01). Women and Socialism - Socialism and Women: Europe Between the World Wars. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781785330063.

- ^ Bolloten, Burnett (1984). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. University of North Carolina Press. p. 1107. ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7.

- ^ "Rescuing Memory: the Humanist Interview with Noam Chomsky" The Humanist TheHumanist.com N. p., 2016. Web. 30 June 2016.

- ^ Dolgoff, S. (1974). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution. ISBN 978-0-914156-03-1.

- ^ a b c Víctor Alba and Stephen Schwartz, Spanish Marxism versus Soviet communism: a history of the P.O.U.M., ISBN 0-88738-198-7, 1988

- ^ a b c Cusick, Lois (1900). The anarchist millenium: memories of the Spanish revolution, 1936-37. OCLC 38776081.

- ^ a b c Horn, G. (2009-02-12). Letters from Barcelona: An American Woman in Revolution and Civil War. Springer. ISBN 9780230234499.

- ^ How the NKVD framed the POUM Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine. What Next? Marxist Discussion Journal.

- ^ Wilebaldo Solano, 1999: "El proceso al POUM: En Barcelona no fué como en Moscú". Archived 2009-09-30 at the Wayback Machine." Fundación Andreu Nin.

- ^ David in Atlanta, 2007: "International Volunteers in the POUM Militias." LibCom.org.

- ^ Biografía: La Pasionaria. Personajes famosos. ABC.es.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ "Newsfeeds". Catholic News Service. 2 April 1937. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b Beever, Antony (2007). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War, 1936 - 1939 (Paperback ed.). London: Phoenix. p. 270.