User:Sria-72/Southeastern Pacific tropical cyclone

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (January 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Tropical cyclogenesis is extremely rare in the far southeastern Pacific Ocean, due to the cold sea-surface temperatures generated by the Humboldt Current, lack of tropical disturbance formation, and also due to unfavorable wind shear; as such, there are no records of a tropical cyclone impacting western South America, though at least six storms have formed since 1983 in the area. Tropical cyclones do however often form in the areas closer to the vicinity of Melanesia and western Polynesia.

Reasons for infrequency of tropical development in the Southeastern Pacific

[edit]

Tropical cyclones generally need multiple ingredients for their formation, such as abundant moisture, low vertical wind shear, and a large difference between sea surface temperature and high-altitude temperatures. In general, tropical cyclones tend to form over warm waters, usually closer to the tropical regions. Although it has been observed that, on some occasions, tropical cyclones can exist in lower temperatures. An example of this is Hurricane Alex of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season.

El Niño events often contribute to the formation of these storms, and have also allowed fairly active cyclone seasons to be recorded in the western South Pacific, such as the 1982-83 and 1997-98 seasons. This phenomenon has allowed the ideal sea surface temperature and humidity conditions to be recorded for the generation of two cyclones, a tropical cyclone in 1983, and a subtropical cyclone in 2015. The cyclone in 1983 occurred at the end of one of the most intense El Niño phenomena recorded, that of 1982-83, which coincided with a very active tropical cyclone season in the South Pacific.

Storms

[edit]

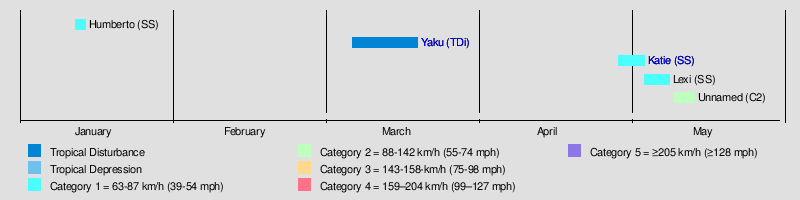

This timeline represents the dates in which the five known systems have formed. This does not take into account the year, they are clearly represented by the month of formation and dissipation.

Pre-2015

[edit]Unnumbered Tropical Cyclone

[edit]| Category 2 tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 10, 1983 – May 14, 1983 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 km/h (65 mph) (10-min); |

On May 10, 1983, the easternmost tropical cyclone developed in the South Pacific, being the closest to South America in the satellite era at the time.[1] Initially, it was named Tropical Depression Two by researchers at the University of Hawaii, because it was the second tropical depression to develop during the 1982-83 South Pacific cyclone season.[2] According to estimates made using the Dvorak technique, the highest sustained wind intensity was close to 65 knots (120 km/h), recorded during the night of May 13, with an estimated minimum pressure between 981 hPa and a Dvorak classification of T4.0, being classified as a category 2 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian and South Pacific cyclone scale. During the early hours of May 14, it began to weaken until it disintegrated on the same day around 12.9°S 115.8°W.[3]

The closest places to this cyclone were Isla de Pascua in Chile, and the island of Fatu-Hiva in French Polynesia.

2015-present

[edit]Subtropical Cyclone Katie

[edit]| Subtropical storm | |

| Duration | April 29, 2015 – May 4, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (1-min); 993 hPa (mbar) |

On April 29, 2015, close to the end of the 2014–15 South Pacific cyclone season, an extratropical cyclone developed in the far Southeastern Pacific, before transitioning into a subtropical depression relatively soon afterward.[4] The storm transitioned into a subtropical depression at 102.9°W, out of the South Pacific basin's eastern boundary of 120°W.[4][5] Around this time, the Chilean Navy Weather Service included the storm in their High Seas Warnings, which kept it there until May 4.[6] During the next couple days, the system moved southwestwards, before turning to the southeast. On May 1, the storm intensified into to subtropical storm intensity, and executed a small westward loop.[4] During this time, the system had encountered sea surface temperatures about 1 °C (1.8 °F) above average and low wind shear, due to an extremely strong El Niño event, allowing the storm to further intensify and organize.[7] On May 2, the storm reached its likely peak intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 72 km/h (45 mph; 39 kn),[4][nb 1] and a minimum low pressure of 993 hPa (29.32 inHg).[6] Around this time, the storm was unofficially named Katie.[7] Katie then tracked westwards, slowly weakening. On May 4, Katie weakened into a subtropical depression and began moving quicker to the northwest, passing to the east of Easter Island, before degenerating into a remnant low.[4][6] On May 6, Katie's remnant low dissipated.[6] During Katie's entire existence, the storm remained east of 120°W, which is not within the official recognized boundary of the basin.[4][6]

Subtropical Cyclone Katie is unofficially the second-easternmost tropical or subtropical cyclone ever observed to form in the South Pacific Ocean, transitioning into a subtropical system near 102.9°W.[7][4] This broke the previous record of around 110°W, set by a tropical depression in May 1983.[8] "Katie" was also the first tropical or subtropical system to form east of the South Pacific basin's official eastern boundary of 120°W[5] since another tropical depression in May 1983.[8] However, in May 2018, Katie's record was broken by Subtropical Cyclone Lexi, which formed just a few hundred miles off the coast of Chile, near 80°W.[9][10] Tropical cyclogenesis is extremely rare in the far southeastern Pacific Ocean, due to the cold sea-surface temperatures generated by the Humboldt Current, lack of tropical disturbance formation, and also due to unfavorable wind shear; as such, there are no records of a tropical cyclone impacting western South America.[11][12][13] Tropical cyclone formation in this extreme part of the Southeast Pacific is so rare that no warning agencies have yet been assigned to the region east of 120°W.[7] Subtropical Cyclone Katie formed during an extremely strong El Niño event; the abnormally-warm waters 1 °C (1.8 °F) above average and low wind shear across the region may have contributed to the system's rare formation.[7] Although Katie's observed characteristics were consistent with that of a subtropical cyclone, detailed analysis revealed that the storm may have briefly transitioned into a tropical cyclone, around the time of its peak intensity.[6]

Subtropical Cyclone Lexi

[edit]| Subtropical storm | |

| Duration | May 4 2018 – May 9, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 992 hPa (mbar) |

On May 4, 2018, a system identified as a subtropical cyclone formed east of 120°W, near 80°W, just a few hundred miles off the coast of Chile, with researchers unofficially naming the storm Lexi.[14] The cyclone formed in an area without a Regional Specialized Meteorological Center, so it was not officially classified.[15] On May 9, the satellite services division of the NOAA classified the system as a weak subtropical storm, despite occurring in cooler (below 20 °C) sea surface temperatures.[16]

Subtropical Cyclone Humberto

[edit]| Subtropical storm | |

| Duration | January 12, 2022 – January 14, 2022 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

On January 13, 2022, the Weather Prediction Center (WPC) noted a subtropical storm approximately 440 nmi (810 km; 510 mi) to the west-southwest of the Juan Fernández Islands.[17] The small storm dissipated the next day.[18] Similar to previous storms that formed in this region, it was unofficially named Humberto by researchers, in honor of Humberto Fuenzalida.[19]

Cyclone Yaku

[edit]

On 7 March, SENAMHI reported an "unorganized tropical cyclone", though no other agencies took note of the storm as a tropical cyclone.[20] SENAMHI researchers were able to identify the formation of the cyclone at the end of February, and also stated that the unusual phenomenon would remain in the Peruvian sea but would not affect any cities on the Peruvian and Ecuadorian coasts. They also reported that moderate to heavy rainfall would develop on the northern coast and highlands of Peru from 9 to 11 March[21] and that the cyclone would not become a hurricane.[22] The system was named "Cyclone Yaku", with the word "Yaku" coming from the Quechuan translation of "water".[23]

Cyclone Yaku brought extreme rainfall conditions to the departments of Tumbes, Piura, and Lambayeque. On 8 March, rainfall was reported in the departments of Tumbes, Piura, Lambayeque, La Libertad, Ancash, and Lima. On 10 March, La Leche River overflows in the Lambayeque Province, affecting the district of Illimo, leaving 3,000 homeless and leaving over 1,000 homes uninhabitable..[24][25] In the department of La Libertad, there was flooding in the provinces of Chepén and Pacasmayo after torrential rains.[25] SENAMHI reports indicated that the departments of Lambayeque and La Libertad exceeded the historical record of rainfall accumulation in 24 hours, reporting values not recorded since the 1997–98 and 2017 El Niño events.[26]

See also

[edit]- Unusual areas of tropical cyclone formation

- South Atlantic tropical cyclones

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclones (medicanes)

- 2006 Central Pacific cyclone

- Tropical Storm Vamei

References

[edit]- ^ https://josevicenciov.wordpress.com/2022/02/15/the-closest-to-south-america-tropical-cyclone-ever-recorded/

- ^ http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/MET/Enso/peu/update.dir/Update-1stQtr98.html

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KlAMs7b3xrA>

- ^ a b c d e f g Steve Young (27 July 2015). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks April 2015". Australia Severe Weather. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

SPAC TCOPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f Blunden, J.; D. S. Arndt (October 2016). "State of the Climate in 2015". State of the Climate. 97 (8). American Meteorological Society: 149–150. Bibcode:2016BAMS...97.....B. doi:10.1175/2016BAMSStateoftheClimate.1. hdl:1874/353366.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Katiewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Pacific ENSO Update — Quarter 1, 1998. Pacific ENSO Update (Report). Vol. 4. The Pacific ENSO Applications Climate Centre. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Levi Cowan (May 7, 2018). "Subtropical Cyclone". Twitter. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ John Leslie (May 9, 2018). "Rare Subtropical Storm off the Coast of Chile". NOAA. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ John Leslie (May 9, 2018). "Rare Subtropical Storm off the Coast of Chile". NOAA. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Jonathan Belles (May 9, 2018). "Extremely Rare Southeast Pacific Subtropical Cyclone Forms Off the Chilean Coast". weather.com. The Weather Company. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Marshall Shepherd (May 10, 2018). "Subtropical Cyclones Don't Normally Form Near Chile - But One Just Did". Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Steve Young (5 July 2018). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks - May 2018". Australia Severe Weather. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Levi Cowan [@TropicalTidbits] (May 7, 2018). "A subtropical cyclone just west of Chile would definitely be among the weirder things I've seen. Water is usually cold there. Colder than 20C in this case, but the thermodynamic profile does support convection" (Tweet). Retrieved February 22, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ John Leslie (May 9, 2018). "Rare Subtropical Storm off the Coast of Chile". NOAA. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ "South American Forecast Discussion". Weather Prediction Center. 2022-01-13. Archived from the original on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ "South American Forecast Discussion". Weather Prediction Center. 2022-01-14. Archived from the original on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ Steve Young (2022). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Tracks, January 2022". Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ "Ciclón Yaku se presenta frente al mar peruano". www.gob.pe (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ^ Sourtech. "Yaku: ¿En qué regiones del Perú se está presentando este inusual ciclón? - Exitosa Noticias". www.exitosanoticias.pe (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ^ "Ciclón Yaku no se convertirá en huracán: Expertos lo descartan, pero se mantienen alerta". infobae (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ Vega, Renzo Gómez (2023-03-11). "Siete fallecidos y miles de damnificados por Yaku, el ciclón que azota la costa y la sierra peruana". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2023-03-15.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Lluvias en Perú | Ciclón Yaku | Lambayeque y La Libertad superaron récord histórico de lluvias desde El Niño de 1998 y El Niño costero del 2017 | Senamhi | PERU". Gestión (in Spanish). 10 March 2023. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Lambayeque en alerta: lluvias torrenciales, desbordes de ríos e inundaciones por el ciclón Yacu". infobae (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).