Mount Elbrus

| Mount Elbrus | |

|---|---|

Mount Elbrus, seen from the north | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,642 m (18,510 ft)[1][2][3] |

| Prominence | 4,741 m (15,554 ft) Ranked 10th |

| Listing | Seven Summits Volcanic Seven Summits Country high point Ultra |

| Coordinates | 43°21′18″N 42°26′21″E / 43.35500°N 42.43917°E |

| Naming | |

| Native name |

|

| Geography | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia |

| Parent range | Lateral Range Caucasus Mountains |

| Topo map(s) | Elbrus and Upper Baksan Valley by EWP[4][5] |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Unknown |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano (dormant) |

| Last eruption | 50 AD ± 50 years[6] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | (West summit) 1874, by Florence Crauford Grove, Frederick Gardner, Horace Walker and the guides Peter Knubel and 22 July 1829 by Killar Khashirov |

| Easiest route | Basic snow/ice climb |

Mount Elbrus[a] is the highest mountain in Russia and Europe. It is situated in the western part of the Caucasus and is the highest peak of the Caucasus Mountains. The dormant volcano rises 5,642 m (18,510 ft) above sea level; it is the highest stratovolcano in Eurasia and the 10th-most prominent peak in the world.[7] The mountain stands in Southern Russia, in the Russian republic of Kabardino-Balkaria.

Elbrus has two summits, both of which are dormant volcanic domes. The taller, western summit is 5,642 metres (18,510 ft);[2] the eastern summit is 5,621 metres (18,442 ft). The eastern summit was first ascended on 10 July 1829 by a Circassian man named Khillar Khashirov, and the western summit in 1874 by a British expedition led by F. Crauford Grove and including Frederick Gardner, Horace Walker and the Swiss guide Peter Knubel.

Etymology

The name Elbrus /ˈɛlbrəs/ seems to have a connection with Alborz[8][9] (also called Elburz), which is also the name of a long mountain range in northern Iran. The name is derived from Avestan Harā Bərəzaitī, a legendary mountain in Iranian mythology. Harā Bərəzaitī reflects Proto-Iranian *Harā Bṛzatī, which was reformed into Middle Persian as Harborz, and into Modern Persian as Alborz.[8] Bṛzatī is the feminine form of the adjective *bṛzant ("high"), the reconstructed ancestor of Modern Ossetian bærzond ("high", "peak"), Modern Persian barz ("high"), berāzande ("elegant"), and boland ("high", "tall"),[8] and Modern Kurdish barz ("high"). Harā may be interpreted as "watch" or "guard", from Indo-European *ser ("protect").[8] Circassians use the name "Uash-ha Makhua" which means "The mountain of happiness", The name "Mingi Taw" used by Karachays and Balkars means "Eternal Mountain" in Turkic languages.[10]

Geography

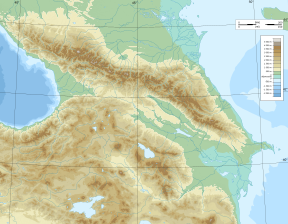

Situation

Elbrus is situated in the northwest of the Caucasus, 100 kilometres from the Black Sea and 370 kilometres from the Caspian Sea, which is visible from Elbrus on exceptionally clear days.[11] It rises 5,642 metres above the sea level. Located eleven kilometres north of the Greater Caucasus Watershed, marking the border with Georgia, it is on the border of the Russian republics of Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia. It is the highest peak in both Russia and Europe.[12]

Elbrus is located 65 kilometres southwest of the city of Kislovodsk and 80 kilometers west-southwest of Nalchik. By road it is accessible from European route E50, known to Russians as either the M29 highway or the R217 highway. Nationalpark Elbrus, which is accessed by the A158 road out of Baksan, lies on its southeastern flank. Access permits are required south of Baksan because of border controls.[citation needed]

Topography

Elbrus is an almost symmetrical dormant volcano, in a vertical plane, with two main peaks, on either side of a pass located at 5,416 metres above sea level: the western summit is the highest point at 5,642 metres above sea level. while the eastern summit rises to 5,621 meters. The crater, 300 to 400 metres in diameter, located at the top of the eastern peak, was gradually filled with snow and ice. The snowfields of the volcano, covering an area of 138 km2, feed 22 (or 23 depending on the source) main glaciers and 77 secondary glaciers that give rise to the Baksan rivers: Kuban and Malka. Some of these glaciers can reach 400 metres in thickness but all are receding, having lost between 80 and 500 meters in length. The two main ones are called Bolshoi Azaou ("the great Azaou"), with an area of 23 km2 and a length of 9.28 km, and Irik, with an area of 10.2 km2 and a length of 9.31 km. This glacial activity has formed numerous small but deep lakes.[citation needed]

Geology

The Caucasus is formed by the northward collision of the Arabian Plate against the Eurasian Plate that causes numerous earthquakes in the region. The fault zone is complex and the large lateral displacement at the level of Anatolia and Iran prevents the creation of a subduction phenomenon and explains the rarity of volcanoes in the mountain range.[citation needed]

Elbrus started to form there 10 million years ago. The ejecta from the volcano covers an area of 260 km². Fragments of rhyolite and rhyodacite as well as tuff and ignimbrite formations have been found and have been allowed by uranium-lead dating to situate the formation of the main caldera around −700,000 years, probably corresponding to the end of a major eruptive cycle. Geochronological dating has revealed subsequent synchronous eruptive cycles in different focimagmatic deposits of the Greater Caucasus, demonstrating the common geological origin of this volcanic activity. It happens that modest fumaroles still sometimes escape from the eastern flank of Elbrus, at the level of the ancient lava flow of 24 kilometers long oriented from the crater to the north-northeast, and hot springs originate on the slopes of the mountain.[citation needed]

Climate

As Elbrus is located in the Northern Hemisphere, the summer period takes place from June to mid-September, with an average of 50% of sunny days favorable to the ascent of the summit. However, the winds, dominated by westerly air masses, can turn violent and temperatures drop very quickly. Above 4000 meters above sea level, even in summer, blizzard conditions with near zero visibility can develop. It is not uncommon for the wind to exceed 100 km/h. In winter, the temperature can drop below −50° at the top. Precipitation increases with altitude.[citation needed]

Mount Elbrus as a whole is warm/hot-summer humid continental (or at the border of oceanic and humid subtropical if the -3 C [27 F] isotherm is used) with hot, moderately wet summers and cold, somewhat dry winters. It is on the border between a Dfa and Dfb climate, at average temperature 72 F (22 C) in July and August. Snow is fairly common, at 45 days a year on average, and winter and late fall are driest.[13] Winters are somewhat moderate for the latitude (~45 N, similar to places like Augusta, Maine, St. Paul, Minnesota, or Boise, Idaho, all of which are colder in winter).

Eruptive history

Mount Elbrus was formed more than 2.5 million years ago. The volcano is currently considered dormant. Elbrus was active in the Holocene, and according to the Global Volcanism Program, the last eruption took place about AD 50.[6] Evidence of recent volcanism includes several lava flows on the mountain, which look fresh, and roughly 260 square kilometres (100 sq mi) of volcanic debris. The longest flow extends 24 kilometres (15 mi) down the northeast summit, indicative of a large eruption. There are other signs of activity on the volcano, including solfataric activity and hot springs. The western summit has a well-preserved volcanic crater about 250 metres (820 ft) in diameter.[6]

History

Greek mythology

In the Periplus of the Euxine Sea, written in Greek in ca. 130, Arrian mentioned a summit in the Caucasus named Strobilos: "… as we turned from Astelphos toward Dioscurias, we saw the Caucasus range […] One peak of the Caucasus was pointed out—the name of the peak was Strobilos—where according to the story Prometheus was hanged by Hephaistos on Zeus' order".[14] (In Greek mythology, the Titan Prometheus was chained in the Caucasus as a punishment for stealing fire from the gods and giving it to mankind.) Arrian's Strobilos, or Latinized Strobilus,[15] was later identified as Elbrus by some writers such as Douglas Freshfield in The Exploration of the Caucasus (1896). Freshfield called Elbrus "pinecone-shaped"[16] for the sake of etymology. The ancient Greek word strobilos denotes rotating or twisted objects such as a spinning top or a pinecone.[17]

Early ascents (1829–1930s)

The lower of the two summits was first ascended on 22 July [O.S. 10 July] 1829 by Khillar Khachirov, a guide for an Imperial Russian army scientific expedition led by General Georgi Emmanuel, and the higher (by about 40 m; 130 ft) in 1874 by an English expedition led by F. Crauford Grove and including Frederick Gardner, Horace Walker, and the Swiss guide Peter Knubel from the Valais canton and guide Ahiya Sottaiev. During the early years of the Soviet Union, mountaineering became a popular sport of the populace, and there was tremendous traffic on the mountain. On 17 March 1936, a group of 33 inexperienced Komsomol members attempted the mountain and ended up suffering four fatalities when they slipped on the ice and fell to their deaths.[18]

Second World War

During the Battle of the Caucasus in World War II, the Wehrmacht occupied the area, surrounding the mountain from August 1942 to February 1943 with Gebirgsjäger from the 1st Mountain Division.[19] The Nazi swastika was placed on the summit of Mount Elbrus on 21 August 1942.[20] A possibly apocryphal story tells of a Soviet pilot being given a medal for bombing the main mountaineering hut, Priyut 11 (Приют одиннадцати, "Refuge of the 11"), while it was occupied. He was later nominated for a medal for not hitting the hut, but instead, the German fuel supply, leaving the hut standing for future generations. When news reached Adolf Hitler that a detachment of mountaineers was sent by Hubert Lanz, the general officer commanding the German division, to climb to the summit of Elbrus and plant the swastika flag at its top, he reportedly flew into a rage, called the achievement a "stunt" and threatened to court martial the general.[21][22] Nazi swastikas were removed by USSR army mountaineers on 13 and 17 February 1943.[23] Mt. Elbrus was briefly incorporated into the Georgian SSR from 1944 - 1957.

Post-WWII

The Soviet Union encouraged ascents of Elbrus, and in 1956 it was climbed en masse by 400 mountaineers to mark the 400th anniversary of the incorporation of Kabardino-Balkaria, the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic where Elbrus was located.

Between 1959 and 1976, a cable car system was built in stages that can take visitors as high as 3,800 metres (12,500 ft).[24]

National park

Since 1986, Elbrus has been incorporated into Prielbrusye National Park, one of the Protected areas of Russia.

Special ascents

In October 2021, Kazakh scientist Aida Tabelinova climbed Mount Elbrus as part of an international expedition led by Youth Club of the Russian Geographical Society and Rossotrudnichestvo to promote humanitarian cooperation.[25] A year earlier, a charity climb for the Global Relief Trust by British Muslim climber Akke Rahman was completed in one day, without acclimatisation or using oxygen, and only days after Rahman recovered from COVID-19 infection.[26]

By vehicle

In 1997 a team led by the Russian mountaineer Alexander Abramov took a Land Rover Defender to the summit of the East Peak, entering the Guinness Book of Records.[27] The project took 45 days in total. They were able to drive the vehicle as high as the mountain huts at The Barrels (3,800 metres (12,500 ft)), but above this they used a pulley system to raise it most of the way. On the way down, a driver lost control of the vehicle and had to jump out. Although he survived the accident, the vehicle crashed onto the rocks and remains below the summit to this day.[28]

In 2016, the Russian climbers Artyom Kuimov and Sergey Baranov entered the Guinness Book of World Records by reaching the summit of Elbrus on ATVs.[29]

With horses

In August 1998 a group of climbers from the Karachai-Cherkess Republic were the first in history to climb Mount Elbrus with horses. The horses were Imbir, Daur and Khurzuk, of the Karachai breed, fitted with special horseshoes with removable steel spikes. The organiser of the climb was Klych-Gery Urusov. Six people reached the eastern summit: three Karachai horsemen (Dahir Kappushev, Mohammed Bidzhiev, Murat Dzhatdoev) and three mountaineers (Boris Begeulov, Umar Bairamukov, Leila Albogachieva (Ingush nationality)), with two of the three horses (Daur and Khurzuk).

A second equestrian climb was made in August 1999 by the same Karachai riders, with a Karachai horse (Igilik), reaching the higher western summit.[30]

A third equestrian ascent took place in 2019, by the Karachai horseman Aslan Khubiev with the Karachai horses Boz and Damly, helped by the Balkar guides Aslan Altuev and Askhat Guzoev.

A fourth equestrian ascent took place on 4 September 2020 (see photo below). Two Karachai horsemen, Ramazan Alchakov and Abrek Ediev, and their Russian friend Ivan Kulaga, together with the two Karachai horses Almaz and Dzhigit, reached the western summit.

A fifth equestrian ascent took place on 23 September 2020 by the Karachai horseman Taulan Achabaev and his cousin Rustam Achabaev, together with the stallion Bahr, reaching the higher western summit accompanied by the Balkar guide Aslan Altuev.

Travel safety

After the collapse of the USSR and until the early 2010s, travel to Mount Elbrus became increasingly dangerous due to economic problems, armed conflicts in various republics of Caucasus, and later due to the North Caucasus insurgency. Currently, Mount Elbrus is steadily becoming an important destination of domestic Russian tourism, with 424,000 visitors to the area in 2020.[31]

As of 2019, the United States Department of State has issued a travel advisory against climbing the mountain, as well as travel to the North Caucasian Federal District in general, due to the risk of terrorism and political instability.[32]

In June 2022, the US State Department advised citizens not to travel to Mount Elbrus, due to terrorism, kidnapping, and risk of civil unrest.[32]

Infrastructure

Refuges

In 1929, eleven scientists erected a small hut at 4,160 metres and called it "Priyut 11" ("Refuge of the 11"). At the same site, a larger hut for 40 people was built in 1932.

A wilderness hut was built in 1933 in the saddle between the two summits but collapsed after only a few years. Its remains can still be seen.

In 1939, the Soviet Intourist travel agency built yet another structure a little above the "Priyut 11" site at 4,200 metres, covered in aluminium siding. It was meant to accommodate western tourists, who were encouraged to climb Mount Elbrus in commercial, guided tours to bring in foreign currency.

Not much later, this hut was converted into a mountain barracks, serving as a base, first for Soviet and later German troops in the Battle of the Caucasus of World War II.

On 16 August 1998, this hut burned down after a cooking stove fell over. After that, the new "Diesel hut" was built in the summer of 2001 a few metres below its ruins, so called because it is located at the site of the former diesel generator station.

In addition, there is accommodation for six people each at the end of the short chairlift above the second cableway section. Painted red and white, these horizontal steel cylinders (called barrels, Russian bochki), are used as a base and for acclimatization by many mountaineers on their way to the summit. Besides the "barrels", there are several container-bases accommodation between about 3,800 and 4,200 metres.

Priyut Hut outhouse

Mount Elbrus is said to be home to the 'world's nastiest' outhouse which is close to being the highest toilet in Europe, at 4,200 m (13,800 ft), next to the old, burnt-out Priyut Hut. The title was conferred by Outside magazine following a 1993 search and article.[33] The "outhouse" is surrounded by and covered in ice, perched on the end of a rock.[11]

Observatory

The Terskol Observatory, an astronomical observatory with the IAU code B18, is located 2.5 km north-west of Terskol village at an altitude of 3,090 metres (10,140 ft).[34][35]

Activities

Ski lifts

Three ski lifts take visitors up to an altitude of 3,847 metres.

Until the mid-2000s, the first section was provided by the Elbrouz-1 cable car, construction of which began in 1959. Starting from the Azaou road at 2,180 metres above sea level in the valley, it leads to the old viewpoint (Stari Krougozor) at an altitude of 2,970 metres; at the foot of the terminal tongue of the Mali glacier Azaou, which has retreated since the construction of the facility. Its length is 1,740 metres, with a drop of 650 meters. The second section, built in 1976, leads to the Mir station at an altitude of 3,470 metres. Its length is 1,800 metres, with a drop of 500 metres. Finally, the last stretch is a chairlift single-seater which then makes it possible to avoid an hour's walk for hikers to the Garabachi huts, at an altitude of 3,847 metres. Built in the late 1970s, it is 1,000 metres long, with a drop of 250 metres.

In December 2006, the first section of the cable car was modernized to meet safety requirements, thanks to the construction of a new cable car in parallel with the existing one. In August 2009, a new cable car was built to reach the second section. On 27 December 2015, the gondola to go up the third section was put into service, thus becoming the second-highest gondola in Europe after that of Zermatt in Switzerland; which is 3,883 m high. Its capacity is 750 people per hour.

The ski resort is busiest in April and May.

Mountaineering

There are a wide variety of routes up the mountain, but the normal route, which is free of crevasses, continues more or less straight up the slope from the end of the cable car system, which takes passengers up to 3,800 metres (12,500 ft). During the summer, it is not uncommon for 100 people to attempt the summit via this route each day. Winter ascents are rare, and are usually undertaken only by very experienced climbers. Elbrus is notorious for its brutal winter weather, and summit attempts are few and far between. The climb is not technically difficult, but it is physically arduous because of the altitude and the frequent strong winds. The average annual death toll on Elbrus is 15–30, primarily due to "many unorganized and poorly equipped" attempts to reach the mountain's summit.[24]

The normal route, on the southern slope, is the easiest, the safest and the fastest, by using the ski lifts to the Garabachi 36 refuges offering 11 cylindrical cabins (the "barrels") of 6 beds each and a total of 80 berths, with water from the melting glacier in summer, and electric heating. At an hour and a half walk, at an altitude of 4,157 metres, is the Diesel refuge, offering 50 places and built in 2001 on the site of the former refuge of the 11 accidentally burned down on Aug 16, 1998. After an additional two hours of walking, the normal route passes close to the Pastoukhov rocks, which can be reached by a snowmobile. The rest of the ascent to the two main peaks can only be done on foot in about six hours. The route is well signposted; but it can be risky to go more than fifty meters from it because of the few crevasses or in the event of being ill equipped. A variant allows you to reach the Diesel refuge from the Ice camp, at an altitude of 3,680 metres.

Another route leads to the summit from Kioukiourtliou-Kolbachi (4,639 m) via the Dome of Koupol at 4,912 meters, on the western side of the mountain. This route, much longer, is accessible either from the first section of the cable car by crossing the moraines in a north-west direction via the Khoti Outaou pass then obliquely towards the summit, or from the Khourzouk valley. There is no refuge but the terrain is more suitable for camping.

Other routes by the east from the valley, the glacier and the Iryk pass (3,667 m), or by the north are possible but are more hazardous due to the absence or obsolescence of the installations.

During Soviet times, Mount Elbrus was home to climbing speed competitions and was training for national Himalayan expeditions (1982 and 1989). The best mountaineers tested their endurance during this prestigious event. In September 1987, Vladimir Balyberdine organized the first official race between the refuge and the pass. In 1990, Anatoli Boukreev set a record by climbing from the refuge to the eastern summit in a time of 1 hour and 47 minutes. In 2005, with the growing enthusiasm for extreme sports and the increase in the number of mountaineers in Russia, this tradition was relaunched and a new race was organized between Bochki and the western summit. In 2006, the best mountaineers from the former Soviet republics participated in the competition: Denis Urubko from Kazakhstan, Sergei Seliverstov and Alexander Kerimov from Kyrgyzstan, and Sergei Sourmonin from Russia. For the first time, one of the routes offers a height difference of over 3,000 metres, starting at the Azaou glades at an altitude of 2,400 metres and arriving at the western summit. Denis Ouroubko sets a time of 3 hours 55 minutes and 58 seconds on this course. On the route starting from the Garabachi huts, Svetlana Sharipova is the best female with a time of 3 hours 21 minutes and 29 seconds.

It is possible to go around Mount Elbrus. The easiest route takes between eight and ten days of hiking, with the crossing of several glaciers and the crossing of many passes. It starts from the village of Baksan in the Kirtyk valley, then passes through the Kirtykaouch pass (3,242 m), descends to the Malka river where it is possible to discover the Sultan Falls from a height of forty metres near the sources. the Jilasu, then connects Khourzouk after the Bourountach pass (3,072 m), and finally crosses the Oullou-Kam river, the Khoti Outaou pass (3,456 m), the Azaou glacier to descend to Terskol and finally return to the point of departure.

In September 2012, an emergency shelter is installed on the "saddle" of Elbrus, between the eastern summit and the western summit, station EG 5300. It was then the highest mountain refuge in Europe. However, the shelter was destroyed by winds in December of the same year. In 2013, a new, more modest emergency shelter, capable of accommodating four to six people, was built 300 metres from the EG 5300 station, by the Russian Mountaineering Federation.

Elbrus Race

The first race on Elbrus took place in 1990, with Soviet and American climbers competing. The race was won by Anatoli Boukreev, with Kevin Cooney in second, followed by Patrick Healy. Route Priut 11 (4,050 m (13,287 ft)) – East (lower) was summited in 1 hour and 47 minutes.[36]

Regular competitions began to take place in 2005, with a choice of two routes: the "classic" climb from "Barrels" at 3,708 m (12,165 ft) to the western summit (5,642 m (18,510 ft)) and a long climb, from the Azau Meadow at 2,350 m (7,710 ft) to the same summit. In 2006, Denis Urubko won the long ascent in 3 hours, 55 minutes, 59 seconds.[36]

On 24 September 2010, under the Artur Hajzer program "Polish Winter Himalayism 2010–2015", the Polish Mountaineering Association sent a 13-person team for training purposes. Andrzej Bargiel set a new long course record of 3 hours, 23 minutes, 37 seconds.[37]

The record time for the full race, ascent and descent, of the long route is 4:20:45, set on 7 May 2017 by the Swiss-Ecuadorian mountain guide Karl Egloff. Egloff broke the previous record set in September 2014 by Vitaliy Shkel by more than 18 minutes. He reached the summit in 3:24:14, missing Bergiel's record ascent-only time by 37 seconds; the race organisation and the International Skyrunning Federation nevertheless consider Egloff's ascent a record as well.[38][39][40]

The fastest times by a woman on the long route were set by Diana Zelenova (4:30:12 for the ascent in 2017) and Oksana Stefanishina (6:25:23 for the full race in 2015).[40]

See also

- List of highest points of Russian federal subjects

- List of elevation extremes by country

- List of volcanoes in Russia

- Seven Summits

- Volcanic Seven Summits

Notes

- ^ Russian: Эльбрус, romanized: Elbrus, IPA: [elʲˈbrus]; Template:Lang-kbd; Template:Lang-krc

References

- ^ "Mount Elbrus". The World Book Encyclopedia. World Book, Inc. p. 317.

- ^ a b "Image of the Day: Mt. Elbrus". NASA Earth Observatory. 7 July 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Topographic map of Mount Elbrus". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Mount Elbrus Map Sample". EWP. 16 June 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Mount Elbrus and Upper Baksan Valley Map and Guide" (Map). EWP. 1:50,000 with mountaineering information. EWP Map Guides. Cartography by EWP. 2007. ISBN 978-0-906227-95-4.

- ^ a b c "Elbrus: Summary". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Russia". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Alborz". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (24 October 2019). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780191882913.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-188291-3.

- ^ Alexander, Eric (2010). The Summit: Faith Beyond Everest's Death Zone. Green Forest: New Leaf Publishing Group, Inc. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-614580232.

- ^ a b Tomb, Howard (27 August 1989). "Getting to the Top In the Caucasus". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "7 (or 8) Summits: The World's Highest Mountains by Continent". Britannica.com.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Stadter, Philip A. (2017). Arrian of Nicomedia. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1364-5. Cf. Arrian, Periplus, Greek text, § 16, and French translation.

- ^ Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Strobilus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- ^ Freshfield, Douglas (1902). The Exploration of the Caucasus, Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. p. 5.

Strobilus—Elbruz we now call it—is still there, lifting its great pinecone-shaped mass over the crest of the central chain.

- ^ "στρόβιλος (ancient Greek)". Wiktionary.

- ^ Kudinov, V.F. "Трагедия на Эльбрусе" [Tragedy on Elbrus]. Poxod.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Landser took photos of them on the summit from August 1942 to February 1943 and the Abwehr and Caucasian Germans were active in that area, until November 1943. "Mount Elbrus: The end of an era". EWP. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Russian Army Repels Hitler's Forces: August 1942-January 1943". Howstuffworks.com. 11 September 2007.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: Nemesis 1936–1945.

- ^ Speer, Albert (1995). Inside the Third Reich. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-842127353.

- ^ Makunin, Yuri (14 February 2002). "Война на Эльбрусе" [War on Elbrus]. Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ^ a b Trubachof, Alex (19 November 2005). "Interview with Boris Tilov - the Chief of the rescue service of Elbrus region". SummitPost. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ Bulatkulova, Saniya (21 October 2021). "Kazakh Scientist Climbs Elbrus With International Expedition to Make Geomaps, Promote Humanitarian Cooperation". The Astana Times. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Chadderton mountaineer sets UK record for mountain climb - days after getting over COVID-19". Oldham Chronicle. 16 October 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Land Rover Defender climbs Mount Elbrus". ExplorersWeb. 18 January 2004. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008.

- ^ Horrell, Mark (9 August 2013). "Chapter 7: The wild side of Elbrus". Elbrus By Any Means. Smashwords. ISBN 978-1-301665822.

- ^ "Квадроцикл на вершине Эльбруса: новый мировой рекорд!" [ATV on top of Elbrus: a new world record!]. Mountain Guide.ru (in Russian). 4 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Traces of Elbrus". The Golden Plaza. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "За 2020 год Приэльбрусье в Кабардино-Балкарии посетили 424 тыс. человек" [In 2020, 424 thousand people visited the Elbrus region in Kabardino-Balkaria]. TASS (in Russian). 21 January 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia Travel Advisory". United States Department of State. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Flinn, John (9 April 2006). "The pinnacle of success—and—disgust—for climbers". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Terskol Observatory". Wikimapia.org.

- ^ "International Center for Astronomical, Medical and Ecological Research". Terskol.com.

- ^ a b "Elbrus Records". Russianclimb.com.

- ^ Karnecki, Marek (24 September 2010). "Polacy najszybsi na Elbrusie" [Poles are the fastest on Elbrus]. Polski Himalaizm Zimowy (in Polish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2013.

- ^ "New records on SkyMarathon® - Mt. Elbrus, 2350-5642 m!". Redfox Elbrus Race. 7 May 2017.

- ^ "Vitaliy Shkel's new great achievement". Elbrusrace.com. 24 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Best performances" (PDF). International Skyrunning Federation. 29 July 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2017.

Further reading

- Huxley, Anthony (1962). Standard Encyclopedia of the World's Mountains. New York City: Putnam.

External links

- "Mount Elbrus". SummitPost.

- Mount Elbrus.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Computer generated summit panoramas North South. There are a few discontinuities due to incomplete data.

- NASA Earth Observatory pages on Mount Elbrus: Mt. Elbrus (July 2003), Mt. Elbrus, Caucasus Range (November 2002)

- "Mt. Elbrus Expedition Dispatches". Berg Adventures International.

- "Elbrus Region". Geographic Bureau.

- KKCTebouTV (3 November 2012). "Horses on Elbrus (5642 m) Лошади карачаевской породы на Эльбрусе". YouTube (in Russian).

- Mountains of Kabardino-Balkaria

- Dormant volcanoes

- Stratovolcanoes of the Caucasus

- Seven Summits

- Volcanic Seven Summits

- Extreme points of Russia

- Stratovolcanoes of Russia

- Mountains of Karachay-Cherkessia

- Volcanoes of Russia

- Five-thousanders of the Caucasus

- Highest points of countries

- Climbing areas of Russia

- Highest points of Russian federal subjects

- Pleistocene stratovolcanoes

- Holocene stratovolcanoes