Nisin

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.370 |

| E number | E234 (preservatives) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C143H230N42O37S7 | |

| Molar mass | 3354.07 g/mol |

| Appearance | powder |

| Density | 1.402 g/mL |

| Boiling point | 2,966 °C (5,371 °F; 3,239 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

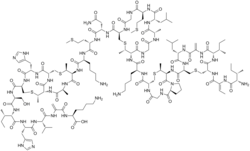

Nisin is a polycyclic antibacterial peptide produced by the bacterium Lactococcus lactis that is used as a food preservative. It has 34 amino acid residues, including the uncommon amino acids lanthionine (Lan), methyllanthionine (MeLan), didehydroalanine (Dha), and didehydroaminobutyric acid (Dhb). These unusual amino acids are introduced by posttranslational modification of the precursor peptide. In these reactions a ribosomally synthesized 57-mer is converted to the final peptide. The unsaturated amino acids originate from serine and threonine, and the enzyme-catalysed addition of cysteine residues to the didehydro amino acids result in the multiple (5) thioether bridges.

Subtilin and epidermin are related to nisin. All are members of a class of molecules known as lantibiotics.

In the food industry, nisin is obtained from the culturing of L. lactis on natural substrates, such as dextrose, and it is not chemically synthesized.

It was originally isolated in the late 1930s, and produced since the 1950s as Nisaplin from naturally occurring sources by Aplin and Barrett in laboratories in Beaminster in Dorset (now owned by International Flavors & Fragrances), and approved as an additive for food use in the US in the late 1960s.[1]

Properties

While most bacteriocins generally inhibit only closely related species, nisin is a rare example of a "broad-spectrum" bacteriocin effective against many Gram-positive organisms, including lactic acid bacteria (commonly associated with avoiding food spoilage), Listeria monocytogenes (a known pathogen), Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium botulinum, etc.[2] It is also particularly effective against spores. Gram-negative bacteria are protected by their outer membrane but may become susceptible to nisin action after a heat shock or when this is coupled with the chelator EDTA. When used in combination with EDTA, nisin can inhibit E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica.[2] Nisin, as a class I bacteriocin, is very stable at acidic pHs and is more heat stable at lower pHs.[2] The mode of action of Nisin against pathogens such as L. monocytogenes is to dissipate the membrane potential and pH gradient.[2]

Nisin is soluble in water and effective at levels nearing the parts-per-billion range. Nisin concentration can be measured using various techniques such as chromatography or by a simple agar diffusion bioassay.[3] Differences between the chromatographic profiles of expired and non-expired nisin samples have been identified. The results of the study indicate the possibility using RP-HPLC for checking the quality and shelf life of commercial nisin samples without the need for additional purification.[4]

Applications

Food production

Nisin is used in processed cheese, meats, beverages, etc. during production to extend shelf life by suppressing Gram-positive spoilage and pathogenic bacteria.[citation needed] In foods, it is common to use nisin at levels ranging from ~1-25 ppm, depending on the food type and regulatory approval. As a food additive, nisin has an E number of E234.

Other

Due to its naturally selective spectrum of activity, it is also employed as a selective agent in microbiological media to isolate gram-negative bacteria, yeast, and moulds.

Nisin has also been used in food packaging applications and can serve as a preservative by controlled release onto the food surface from the polymer packaging.[5]

In combination with miconazole it has been studied as a possible treatment for infections of Clostridium difficile.[citation needed]

Further reading

- Fukase, Koichi; Kitazawa, Manabu; Sano, Akihiko; Shimbo, Kuniaki; Fujita, Hiroshi; Horimoto, Shingo; Wakamiya, Tateaki; Shiba, Tetsuo (1988). "Total synthesis of peptide antibiotic nisin". Tetrahedron Letters. 29 (7): 795–798. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80212-9. (Total synthesis)

- Buchman, GW; Banerjee, S; Hansen, JN (1988). "Structure, expression, and evolution of a gene encoding the precursor of nisin, a small protein antibiotic". J Biol Chem. 263 (31): 16260–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)37587-2. PMID 3141403. (Biosynthesis)

- http://medicalxpress.com/news/2012-10-common-food-tumor-growth.html

- https://phys.org/news/2024-02-common-food-unexpected-effects-gut.amp

- Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology - Page 187 books.google.ae/books?ISBN 0123847338

References

- ^ ageconsearch

.umn .edu /bitstream /90779 /2 /CP%2001%2005%20Nisin%20Report .pdf - ^ a b c d And, H. Chen; Hoover, D. G. (2003). "Bacteriocins and their Food Applications". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2 (3): 82–100. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00016.x. ISSN 1541-4337. PMID 33451234.

- ^ Chandrasekar, Vaishnavi (2015). "Modeling development of inhibition zones in an agar diffusion bioassay". Food Science and Nutrition. 3 (5): 394–403. doi:10.1002/fsn3.232. PMC 4576963. PMID 26405525.

- ^ Artur Martynov, Oksana Knysh (August 2023). "HPLC-pharmaceutical Analysis of Lantibiotic Nisin in the Industrial Samples Including Expired Sample" (PDF). Methods and objects of chemical analysis. 18 (2): 87–91. doi:10.17721/moca.2023.87-91.

- ^ Chandrasekar, Vaishnavi (2017). "Release Kinetics of Nisin from Chitosan–Alginate Complex Films". Journal of Food Science. 81 (10): E2503 – E2510. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.13443. PMID 27635864.