Close-Up (1990 film)

| Close-Up | |

|---|---|

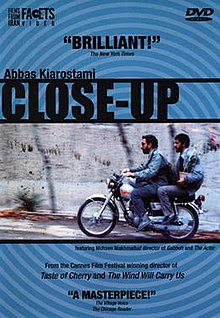

DVD cover | |

| کلوزآپ ، نمای نزدیک | |

| Directed by | Abbas Kiarostami |

| Written by | Abbas Kiarostami |

| Produced by | Ali Reza Zarrin |

| Starring | Hossain Sabzian Mohsen Makhmalbaf |

| Cinematography | Ali Reza Zarrindast |

| Edited by | Abbas Kiarostami |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Celluloid Dreams |

Release date | 1990 |

Running time | 98 min. |

| Country | Iran |

| Language | Persian |

Close-Up (Template:Lang-fa, Klūzāp, nemā-ye nazdīk) is a 1990 Iranian docufiction written, directed and edited by Abbas Kiarostami. The film tells the story of the real-life trial of a man who impersonated film-maker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, conning a family into believing they would star in his new film.[1] It features the people involved, acting as themselves. A film about human identity, it helped to increase recognition of Kiarostami internationally.

Close-Up is considered to be one of the greatest films of all time; in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, it was voted by critics one of "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time" list.[2] In the 2022 Sight and Sound critics' poll it was rated the 17th greatest film of all time.

Story

Hossain Sabzian is a cinephile, and in particular a big fan of popular Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. One day, Sabzian is riding a bus with a copy of a published screenplay of The Cyclist; Mrs. Ahankhah sits next to him, revealing she is a fan of the film. Sabzian tells her that he himself is Makhmalbaf, the creator and learns that her sons are interested in film. Posing as Makhmalbaf, Sabzian visits the Ahankhah family several times over the next two weeks. He flatters them by saying he wants to use their house in his next film and their sons as actors. He also borrows 1,900 tomans from one of the sons for cab fare. Mr. Ahankhah starts to suspect him as an imposter trying to rob them, especially when a magazine photograph shows a younger Makhmalbaf with darker hair. He invites a journalist, Hossain Farazmand, who confirms that Sabzian is indeed an impostor. The police come to arrest Sabzian, while Farazmand takes several pictures for his upcoming article titled "Bogus Makhmalbaf Arrested".[3]

Kiarostami visits Sabzian in prison and helps to move his trial up, and receives permission from the judge to record the trial. At the trial, Sabzian is tried for fraud and attempted fraud. He reveals his motivations for the imitation as love for Makhmalbaf's film and cinema, while the Ahankhah's son recounts his visits as they started to suspect him. Due to his circumstances as a young father with no prior record and his remorse, the judge asks the family if they would be willing to pardon Sabzian. They agree in exchange for him becoming a productive member of society. After the trial, the real Makhmalbaf meets Sabzian and gives him a ride back to the Ahankhah's house, with Kiarostami's crew following. When they meet Mr. Ahankhah, he says of Sabzian: "I hope he'll be good now and make us proud of him."

Cast

- Hossain Sabzian as himself

- Mohsen Makhmalbaf as himself

- Abbas Kiarostami as himself

- Abolfazl Ahankhah as himself

- Mehrdad Ahankhah as himself

- Monoochehr Ahankhah as himself

- Mahrokh Ahankhah as herself

- Haj Ali Reza Ahmadi as himself, the Judge

- Nayer Mohseni Zonoozi as herself

- Ahmad Reza Moayed Mohseni as himself, a family friend

- Hossain Farazmand as himself, a reporter

- Hooshang Shamaei as himself, a Taxi Driver

- Mohammad Ali Barrati as himself, a Soldier

- Davood Goodarzi as himself, a Sergeant

- Hassan Komaili as himself, a Court Recorder

- Davood Mohabbat as himself, a Court Recorder

Notes

The film references one of Kiarostami's previous films, the 1974 football drama The Traveler (considered by the director to be his first 'authentic' feature).[5]

It also mentions The Cyclist, a 1987 sports drama film made by the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf three years prior to Close-Up.[6]

Production

Close-Up is based on real events that occurred in Northern Tehran in the late 1980s. Kiarostami first heard about Sabzian in 1989 after reading about the incident in an article in the Iranian magazine Sorush by journalist Hassan Farazmand. Kiarostami immediately suspended work on the film project that he was in pre-production of and began making a documentary on Sabzian. Kiarostami was allowed to film Sabzian's trial and also got Sabzian, the Ahankhahs and Farazmand to agree to participate in the film and to re-enact incidents from the past. Kiarostami also arranged for Mohsen Makhmalbaf to meet Sabzian and help facilitate forgiveness between Sabzian and the Ahankhahs.[7]

Critical reception

When the film opened in Iran, reviews were almost uniformly negative, and the film only began to be appreciated after it was shown abroad.[8] The New York Times film critic Stephen Holden called the film "brilliant," noting its "radically drab cinema-verite style that helps blur any difference between what is real and what is reconstructed."[9]

In 2010 Los Angeles Times critic Dennis Lim called the film eloquent and direct and that it provided "a window into the psyche of a complicated man and into the social and cultural reality of Iran."[10] In 2022, it ranked #17 in the British Film Institute's critics' poll of BFI The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time

Influence

Five years after Close-Up, Moslem Mansouri and Mahmoud Chokrollahi wrote and directed the documentary Close-Up Long Shot (Template:Lang-fa, Klūzāp nemā-ye dūr) in which Sabzian talks about his infatuation with cinema, his impersonation of Makhmalbaf and how his life has changed after working with Kiarostami. The film premiered at Turin's 14° Festival internazionale cinema giovani in November 1996 where it won the FIPRESCI Prize – Special Mention.[11][12]

Nanni Moretti's 1996 Italian short film Opening Day of Close-Up follows a theater owner as he prepares to show Kiarostami's film at his independent cinema.

Marcus Söderlund's 2007 music video for Swedish duo The Tough Alliance's "A New Chance" pays homage to Kiarostami's film with an almost shot-for-shot reproduction of a scene following two characters on a motorcycle.[13]

Martin Scorsese in an interview for the Criterion edition of the 2019 film Rolling Thunder Revue cites Kiarostami as his main influence.

In 2012, filmmaker Ashim Ahluwalia included the film in his personal top ten (for The Sight & Sound Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time poll), writing: "A re-enactment of a re-enactment of a re-enactment, Close Up essentially destroys the very conception of a 'documentary' and yet is one of the best ever made."[14]

Aftermath

In 2006, Hossain Sabzian died at age 52 after suffering a heart attack. He suffered respiratory failure on the Tehran metro in August, slipped into a coma, and died on September 29.[15][16]

Trivia

- In the first scene, Hossain Farazmand tells the taxi driver Hooshang Shamaei while driving to Ahankhah's place about the "Oriana story" citing Oriana Fallaci's tendencies to dig up stories about the most exclusive topics. He also mentions other internationally reputed reporters Peter Bogdanovich and John Edisson.

Awards

- 1990: Montreal International Festival of New Cinema and Video: Quebec Film Critics Award[17]

- 1992: International Istanbul Film Festival: FIPRESCI Prize[18]

See also

- F for Fake (1973) – the last major film completed by Orson Welles, who directed, co-wrote, and starred in the film, which is loosely a documentary that operates in several different genres and has been described as a kind of film essay.

- Hello Cinema (1995) – an Iranian docufiction film directed by Mohsen Makhmalbaf that shows various everyday people being auditioned and explaining their reason for wanting to act in a film.

- Colour Me Kubrick (2005) – a British film directed by Brian W. Cook about the true story of a man who pretended to be director Stanley Kubrick, a similar premise to this film.

- List of docufiction films

- Metafilm

References

- ^ "DVD of the Week: Close-Up". The New Yorker.

- ^ "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ These scenes are shown in flashback throughout the film and were re-enacted.

- ^ TCM.com

- ^ "The Traveler - Close-up". The Criterion Channel.

- ^ "Bicycleran (1989)". IMDb.

- ^ "Close-up: Prison and Escape". www.criterion.com. June 22, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ Cheshire, Godfrey. "Close-up: Prison and Escape". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Holden, Stephen, "Close Up (1990) FILM REVIEW; The Pathos Of Deceit By a Victim Of Longing." The New York Times, December 31, 1999, Accessed on November 17, 2012.

- ^ Lim, Dennis, "A Second Look: Abbas Kiarostami's 'Close-Up'." Los Angeles Times, June 9, 2010, Accessed on November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Close-Up Long Shot (Forum, Film Festival Berlin 1997)". arsenal-berlin.de. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Torino Film Festival". torinofilmfest.org. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ The Tough Alliance - A New Chance. 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 14 March 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ "BFI". www.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016.

- ^ Cheshire, Godfrey. "Close-up: Prison and Escape". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ Bidoun. "The Most Fatal Attraction: Kiarostami's 'Close-Up' revisited". Bidoun. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ "Montréal Festival of New Cinema (1990)". IMDb.

- ^ "Istanbul International Film Festival (1992)". IMDb.

Bibliography

- Godfrey Cheshire, Confessions of a Sin-ephile: Close Up, Cinema Scope, no. 2 (Winter 2000), pp. 3–8

- Cristina Vatulescu, "The Face to Face Encounter of Art and Law": Abbas Kiarostami's Close-Up, Law and Literature, vol. 23, no. 2 (Summer 2011), pp. 173–194

External links

- Close-Up at IMDb

- Template:AllMovie title

- An 'Islamic' reading of Kiarostami's Close-Up

- Close-Up at the Arts & Faith Top100 Spiritually Significant Films list

- Slant magazine article

- Combustible Celluloid review

- Interview to The Guardian, Thursday 28 April 2005

- Close-up: Prison and Escape an essay by Godfrey Cheshire at the Criterion Collection