History of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

The indigenous inhabitants of the islands of St. Vincent and the Grenadines were various Amerindian groups. The arrivals of Europeans in the early 16th century did not lead to long term settlement, only in 1717 did the French occupy the island in Barrouallie, though the English laid claim on St. Vincent in 1627. The Treaty of Paris (1763) saw St. Vincent ceded to Britain. Frictions with the British led to the First and Second Carib War in the mid- to late-18th century but the British held on to the islands. A Crown Colony government was installed in 1877, a Legislative Council created in 1925, and universal adult suffrage granted in 1951. Following a referendum in 1979, St. Vincent and the Grenadines became the last of the Windward Islands to gain independence on 27 October 1979.

Pre-colonial history

[edit]Before the arrival of Europeans and Africans in the 16th century, various Amerindian groups passed through or settled on St. Vincent and the Grenadines, including the Ciboney, Arawak, and Carib people.[1] These groups likely originated in the Orinoco Valley of South America and migrated north through Trinidad and the Lesser Antilles.

By the time Christopher Columbus passed near St. Vincent on his third voyage in 1498, the Caribs occupied the island after displacing the Arawaks a few centuries earlier.

Early European contacts

[edit]

Columbus and the Spanish conquistadors largely ignored St. Vincent and the smaller Grenadine islands nearby, but focused instead on the pursuit of gold and silver in Central and South America. They did embark on slaving expeditions in and around St. Vincent following royal sanction in 1511, driving the Carib inhabitants to the rugged interior, but the Spanish made no attempt to settle the island.[2]

Carib Indians aggressively prevented European settlement on St. Vincent until the 18th century. African slaves, whether shipwrecked or escaped from St. Lucia or Grenada and seeking refuge in St. Vincent, intermarried with the Caribs and became known as "black Caribs". Now those of mixed African-Carib ancestry are known as Garifuna.

French and British colonisation and the Carib Wars

[edit]

The first Europeans to occupy St. Vincent were the French. However, following a series of wars and peace treaties, the islands were eventually ceded to the British. While the English were the first to lay claim to St. Vincent in 1627, the French (centred on the island of Martinique) would be the first European settlers on the island when they established their first colony at Barrouallie on the Leeward side of St. Vincent in 1719.[3] The French settlers cultivated coffee, tobacco, indigo, corn, and sugar on plantations worked by African slaves.

St. Vincent was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Paris (1763). From 1763 until independence, St. Vincent passed through various stages of colonial status under the British.

Friction between the British and the Caribs led to the First Carib War. The First Carib War (1769–1773) was fought over British attempts to extend colonial settlements into Black Carib territories, and resulted in a stalemate and an unsatisfactory peace agreement. Led primarily by Black Carib chieftain Joseph Chatoyer, the Caribs successfully defended the windward side of the island against a military survey expedition in 1769, and rebuffed repeated demands that they sell their land to representatives of the British colonial government. Frustrated by what they saw as intransigence, the British commissioners launched a full-scale military assault on the Caribs in 1772 with the objective of subjugating and deporting them from the island. British unfamiliarity with the windward lands of the island and effective Carib defence of the island's difficult mountain terrain blunted the British advance, and political opposition to the expedition in London prompted an enquiry and calls for it to be ended. With military matters at a stalemate, a peace agreement was signed in 1773 that delineated boundaries between British and Carib areas of the island.

A representative assembly was authorized by the British in 1776. France captured Saint Vincent in 1779 during the American War of Independence, but it was restored to Britain by the Treaty of Versailles (1783).

The Second Carib War begun in March 1795 by the Caribs, who harboured long-standing grievances against the British colonial administration, and were supported by French Revolutionary advisors including the radical Victor Hugues. The Caribs successfully gained control of most of the island except for the immediate area around Kingstown, which was saved from direct assault on several occasions by the timely arrival of British reinforcements. British efforts to penetrate and control the interior and windward areas of the island were repeatedly frustrated by incompetence, disease, and effective Carib defences, which were eventually supplemented by the arrival of some French troops from Martinique. A major military expedition by General Ralph Abercromby was eventually successful in crushing the Carib opposition in 1797. More than 5,000 black Caribs were deported from Saint Vincent first to the island of Baliceaux, off Bequia, where half of them died in concentration camps, and then to the island of Roatán off the coast of present-day Honduras, where they later became known as the Garifuna people.

Like the French before them, the British also used African slaves to work plantations of sugar, coffee, indigo, tobacco, cotton and cocoa. Decades after the success of the Haitian Revolution, the British abolished slavery in 1834; full emancipation was achieved in 1838. The economy then went into a period of decline with many landowners abandoning their estates and leaving the land to be cultivated by liberated slaves. The resulting labour shortages on the plantations attracted Portuguese immigrants in the 1840s and East Indians in the 1860s as laborers. Conditions remained harsh for both former slaves and immigrant agricultural workers, as depressed world sugar prices kept the economy stagnant until the turn of the 20th century.

A Crown Colony government was installed in 1877, a Legislative Council created in 1925, and universal adult suffrage granted in 1951. During this period, the British made several unsuccessful attempts to affiliate St. Vincent with other Windward Islands in order to govern the region through a unified administration. The most notable was the West Indies Federation, which collapsed in 1962.

The La Soufriere volcano erupted in 1812 and 1902 when much of the island was destroyed and many people were killed. In 1979 it erupted again, this time with no fatalities. In the same year, St Vincent and The Grenadines gained full independence from Britain, while remaining a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

-

Depiction of treaty negotiations between Black Caribs and British authorities on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent in 1773 (1910)

-

Joseph Chatoyer, the chief of the Black Caribs in St.Vincent, in an 1801 engraving

-

Engraving 'after Agostino Brunias' (ca 1801) entitled A Negro Festival drawn from Nature in the Island of St Vincent. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

-

"View of the botanic garden in St Vincent", from "An account of the botanic garden in the island of St Vincent, from its first establishment to the present time" by Lansdown Guilding. Glasgow: Richard Griffin & Company, 1825

-

Bunkers Hill, Richmond Estate, Saint Vincent. May 30, 1902 This ridge, near the Wallibou river, shows the dendritic drainage system gradually creeping to crest of the ridge. Material along crest is fine dust, which rains formed into a cement-like coat.

-

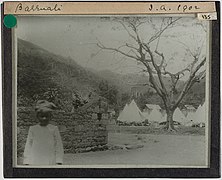

Barrouallie, tent camp for people displaced by the 1902 eruption of the Soufrière

Self-rule and independence

[edit]

St. Vincent was granted associate statehood status on 27 October 1969, giving it complete control over its internal affairs. Following a referendum in 1979, St. Vincent and the Grenadines became the last of the Windward Islands to gain independence on 27 October 1979.

In November 2020, Ralph Gonsalves, Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines since 2001, made history by securing the fifth consecutive victory of his Unity Labour Party (ULP) in general election.[4]

Natural disasters

[edit]Natural disasters have plagued the country throughout the 20th century. In 1902, Soufrière volcano erupted, killing 2,000 people. Much farmland was damaged, and the economy deteriorated. In April 1979, La Soufrière erupted again. Although no one was killed, thousands had to be evacuated, and there was extensive agricultural damage.

The island also suffers from hurricanes. On 11 September 1898, six hours of a terrible hurricane devastated Barrouallie, which was almost completely destroyed. More recently, in 1980 and 1987, hurricanes devastated banana and coconut plantations; 1998 and 1999 also saw very active hurricane seasons, with Hurricane Lenny in 1999 causing extensive damage to the west coast of the island.

In 2021, on 9 April, the La Soufrière volcano erupted, sending ash several miles into the atmosphere. Approximately 16,000 people were evacuated in the days leading up to the eruption.[5]

See also

[edit]- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of North America

- History of the Caribbean

- List of prime ministers of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Politics of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

References

[edit]- ^ Forte, Maximilan (June 2014). "Yurumein (Homeland): A Documentary on Caribs in St. Vincent". Review of the Indigenous Caribbean.

- ^ Rogozinski (January 2000), A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present. Plume, New York, New York.

- ^ "St. Vincent Timeline". St. Vincent Genealogy Resources. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Ralph romps to fifth straight election win in St Vincent and the Grenadines". jamaica-gleaner.com. 5 November 2020.

- ^ Wilson Wong, The Associated Press (9 April 2021). "Explosive eruption rocks volcano on Caribbean's St. Vincent". NBC News.

Further reading

[edit]- Gonsalves, Ralph E. 2007. History and the Future: A Caribbean Perspective. Kingstown, St. Vincent: Quik-Print.

- Morse, J. (1797). "St. Vincent". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews. OL 23272543M.

- Rogozinski, January 2000. A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present. New York, New York: Plume.

- Williams, Eric. 1964. British Historians and the West Indies, Port-of-Spain: P.N.M. Publishing.