Educational attainment in the United States

The educational attainment of the U.S. population refers to the highest level of education completed.[2] The educational attainment of the U.S. population is similar to that of many other industrialized countries with the vast majority of the population having completed secondary education and a rising number of college graduates that outnumber high school dropouts. As a whole, the population of the United States is spending more years in formal educational programs. As with income, levels differ by race, age, household configuration, and geography.[3]

Information on educational attainment of the U.S. population has been collected in every decennial census since 1940.[4] At a national level, reports show rates of educational attainment by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. Differing at the regional and state levels, educational attainment data are shown by sex, race, and Hispanic origin (not age).[4]

Overall, the demographics with the highest educational attainment in the United States are also those with the highest household income and wealth.[3] Indian-Americans are the highest-earning and the highest-educated ethnic group in the United States, as of the 2020 U.S. Census.[5]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

| Summary |

| Curriculum topics |

| Education policy issues |

| Levels of education |

|

|

General attainment of degrees/diplomas

| Education | Age 25 and over | Age 25-30 |

|---|---|---|

| High school diploma or GED | 89.80% | 92.95% |

| Some college | 61.28% | 66.34% |

| Associate degree | 45.16% | 46.72% |

| Bachelor's degree | 34.98% | 36.98% |

| Master's degree | 13.04% | 9.01% |

| Professional degree | 3.47% | 2.02% |

| Doctorate | 2.03% | 1.12% |

In 2018, nearly 9/10 (90 percent) of all adults 25 years or older reported they had completed at least high school, or obtained a GED/high school equivalency certificate. Over one in three adults (35 percent) had attained at least a bachelor's degree. Both of these measures are all time highs. In 2003, the percentage of the adult population who had completed high school or had not completed high school but obtained a GED increased for the first time since 2000, when it was 84 percent. This increase follows a general trend that the Current Population Survey has shown since educational attainment was first measured in 1947.[3]

Since 1983, the percentage of people either graduating from high school or failing to complete high school but getting a GED certification has increased from 85% to 90%. The greatest increases in educational attainment were documented in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. In the 1950s and much of the 1960s high school graduates constituted about 50% of those considered adults (25 and above). For adults aged between 25 and 30, the percentage of either high school graduates or GED obtainers was roughly 50% in 1950 versus 90% today.[3]

According to The United States Census Bureau,[4] from 1940 to 1980, respondents were asked to what their highest grade or year of school completed was. Here are two examples of the questions asked:

- What is the highest grade (or year) of school this person has ever attended?

- Did he finish the highest grade (or year) he attended?

The answers consisted mostly of the following:

- No school completed or never attended school

- Nursery school (added as a choice in 1960)

- Elementary school, grades 1, 2, 3, etc. to 8

- High school 1st to 4th year…1, 2, 3, 4

- College, 1st year, 2nd year, etc.

However, in 1990, the Census Bureau changed educational attainment question as society became more educated as a whole. Now, respondents are asked to report what their highest level of school/highest degree received is. Responses may include; "High school graduate" and "Bachelor's degree."[4]

Gender

For the past fifty years, there has been a gap in the educational achievement of males and females in the United States, but which gender has been underperforming has fluctuated over the years. In the 1970s and 1980s, data showed girls trailing behind boys in a variety of academic performance measures, specifically in test scores in math and science.[7]

Data in the last twenty years[when?] shows the general trend of girls outperforming boys in academic achievement in terms of class grades across all subjects and college graduation rates, but boys score higher on standardized tests and are better represented in higher-paying and more prestigious STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math).[7]

Employment Rates Linked to Gender and Educational Attainment

While the correlation between educational achievement and employment rates applies to both men and women, it's notably stronger for women. In 2021, among individuals aged 25–34, only 43% of women with education below the upper secondary level were employed, compared to 82% of those with tertiary education. For men, these figures were 69% and 88%, respectively.[8] The significant gender gap observed among younger adults with education below the upper secondary level is unlikely solely due to differences in employability; rather, it's more likely tied to the persistence of traditional gender roles. Women who anticipate fulfilling caregiving responsibilities at home instead of pursuing careers may have less motivation to pursue formal education, leading to lower educational attainment. This is evidenced by the fact that inactivity rates among younger women with education below the upper secondary level are, on average, more than twice as high as those for men, resulting in lower employment rates across OECD countries.

Gender gap in literacy

Traditionally, girls have outperformed boys in reading and writing. Although this gap may be minimal in kindergarten, it grows as students continue their education. According to the 2004 National Reading Assessment measured by the US Department of Education, the gap between boys and girls, only slightly noticeable in 4th grade, left boys 14 points behind girls during their 12th grade year.[9] On the 2008 test, female students continued to have higher average reading scores than male students at all three ages. The gap between male and female 4th graders was 7 points in 2008. By 12th grade, there was an 11-point gap between males and females.[9]

On the 2002 National Writing Assessment, boys scored on average 17 points lower than girls in 4th grade. The average gap increased to 21 points by 8th grade and widened to 24 points by senior year in high school.[10] In the more recent 2007 National Assessment of Writing Skills, female students continued to score higher than male students, though margins closed slightly from previous assessments. The average score for female eighth-graders was 20 points higher than males, down 1 point from the 2002 score. For twelfth-graders, females outscored males by 18 points as opposed to 24 points in 2002.[11]

All of these assessments were conducted on a 100-point scale.[9][10][11]

A recent study has since discovered that many schools are not heavily focused in the performance of how young males grow in their educational development as they are with girls. [45].

Women have different issues in educational attainment. New studies have shown that, when it comes to completing their education, women are pushed to go after a bachelor degree but that financial issues affect them. [46]

Graduation rates

Overall, women have surpassed men in terms of completion of secondary and post-secondary education. In 2015/2016, women earned 61% of associate degrees, 57% of bachelor's degrees, 59% of master's degrees, and 53% of doctorates.[12] A similar pattern is also seen in high school education, where, in 2016, 7.1% of males, but only 5.1% of females dropped out of high school.[13]

In 2015/2016, 56 percent of college students were female and 44 percent were male. From 1990 until 2015, the number of males enrolled in college increased by 41 percent, and the number of female students rose by 53 percent.[12] In 2015/2016, 51% of degrees earned by males were bachelor's, which is slightly higher than that of females for whom 48% of degrees earned were bachelor's degrees.[12] As of 2006, the numbers of both men and women receiving a bachelor's degree has increased significantly, but the increasing rate of female college graduates exceeds the increasing rate for males.[14]

In 2007, the United States Census Bureau estimated that 18,423,000 males over the age of 18 held a bachelor's degree, while 20,501,000 females over the age 18 held one. In addition, fewer males held master's degrees: 6,472,000 males compared to 7,283,000 females. However, more men held professional and doctoral degrees than women. 2,033,000 males held professional degrees compared to 1,079,000, and 1,678,000 males had received a doctoral degree compared to 817,000 females.[15]

Women were projected to earn 64.2% of associate degrees, 59.9% of bachelor's degrees, 62.9% of master's degrees, and 55.5% of Doctorates by 2016/2017.[16]

Gender Gaps and communities

The increase in educational attainment has slightly increased in certain communities. In the stat below you can see that there is not a huge shift in Asian communities from 2010 to 2022 in comparison to African-American and white communities there has been an increase in those communities achieving their degrees. [47].

There have been reports as of last year stating that there have not been much improvements of marginalized communities going to college because that increase is ever so slight.

- African- American enrollments are down 22%

- Caucasian enrollments are down 7%

Other communities reports are not as open to the public as we mainly focus on the two main communities when it comes to educational status and that itself is an issue because education is a topic that affects every person because that is the system we are born into and that we either have the choice to continue or not given certain circumstances.

Ethnicity and race

While the educational attainment of all races increased during the 1990s, with the gap between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites decreasing, differences between the races remain, especially among those with a bachelor's degree or higher. Asian Americans had the highest educational attainment of any race, followed by whites who had a higher percentage of high school graduates but a lower percentage of college graduates. Persons identifying as Hispanic or Latino, without regard to race, had the lowest educational attainment. The gap was the largest between foreign-born Asian Americans, over half (50.1%) of whom had a bachelor's degree or higher and foreign-born Hispanics, 9.8% of whom had a four-year college degree.[3]

Hispanics and Latinos also trailed far behind in terms of graduating from high school; it was the only major group for which high school graduates constituted less than 80% of the population. This large inequality might partially be explained by the influx of uneducated foreign-born Hispanic Americans who had not been offered the chance to complete secondary education in their home country and who had not completed secondary education in the United States.

Overall, nearly half (49.8%) of Asian Americans, nearly a third (30%) of non-Hispanic whites, 17.3% of non-Hispanic blacks, and just over a tenth (11.4%) of Hispanics or Latinos had a four-year college degree. The same differences decrease significantly at the high school level with 89.4% of non-Hispanic whites, 87.6% of Asian Americans, 80.0% of African Americans, and 57% of Hispanics or Latinos having graduated from high school.[3]

In 2015, the average SAT scores on the math section were 598 for Asian-Americans, 534 for whites, 457 for Hispanic Latinos and 428 for blacks.[17] Additionally, 10% of Asian-Americans, 8% of whites, 3% of Mexican Americans, 3% of Native Americans and 2% of blacks scored above 600 on the SAT verbal section in 1990.[18] Race gaps on the SATs are especially pronounced at the tails of the distribution. In a perfectly equal distribution, the racial breakdown of scores at every point in the distribution should ideally mirror the demographic composition of test-takers as whole i.e. 51% whites, 21% Hispanic Latinos, 14% blacks, and 14% Asian-Americans. But among the highest top scorers, those scoring between a 750 and 800 (perfect scores) over 60% are East Asians of Taiwanese, Japanese, Korean and Han Chinese descent, while only 33% are white, compared to 5% Hispanic Latinos and 2% blacks.[17] In August 2020, the US Justice Department argued that Yale University discriminated against Asian candidates on the basis of their race, a charge the university denied.[19]

The Racial achievement gap in the United States refers to these educational disparities between differing ethnic groups. Several racial achievement gaps remain present today because not all groups of students are advancing at the same rates. These racial achievement gaps have many individual and economic implications and there have been many efforts in education reform to narrow the gaps.

Immigrants

Among some broad ethnic groups, notably Asians, Europeans, and Africans, foreign-born immigrants show a higher educational attainment than native-born Americans in the same group. According to the U.S census, African immigrants achieved the most college degrees at about 43.8 percent, compared to 42.5 percent of Asian-Americans, 28.9 percent for immigrants from Europe, Russia and Canada and 23.1 percent of the U.S. population as a whole.[20][21][22]

The opposite is true among Hispanics, where the dramatically lower educational attainment of the foreign-born population decreased the overall educational attainment of the general Hispanophone population.[3] The rate of immigrants

with a high school diploma (67 percent) was dramatically lower than that of the native population (88 percent), but paradoxically, the percentage with a bachelor's degree was the same (27 percent)... At the bachelor's level, foreign born blacks and non-Hispanic whites fared better than their native counterparts. Foreign-born Hispanics, in contrast, had a smaller proportion with a bachelor's degree than the native population... The low educational attainment of foreign-born Hispanics, who compose more than 50 percent of the Hispanic population, contributes to the low attainment levels of the entire Hispanic population.

— US Census Bureau, 2003

Only among Hispanics and Latinos was the proportion of college graduates larger among the native born population. In the general population the proportion of persons with a bachelor's degree or higher was the same among the foreign-born and native-born population (27.2%). As stated above fewer foreign born Americans completed high school than native born Americans. Overall, 87.5% of the native born population had graduated from high school, versus 67.2%. Among whites the difference was three percentage points, the same as for African Americans. Among Asian Americans the difference was five percentage points. It was thirty percentage points among Hispanics or Latinos.[3]

African immigrants have been among the more highly educated group in the United States since the 1990s.[23][24] This phenomenon is related to the large "brain drain" in Africa.[25]

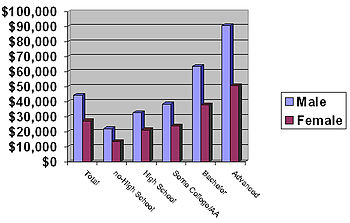

Income

Educational attainment is strongly correlated with income in the United States. Although the incomes of both men and women are associated with higher educational attainment (higher incomes for higher educational attainment), large income gaps linked to race and gender remained at each educational level. In 2003, average incomes ranged from $13,459 for a male high-school dropout to $90,761 for a male with an advanced degree. The most significant average income difference was between those who had some college education or an associate degree and those who had a bachelor's degree. While those with some college averaged $31,046, those with a bachelor's degree averaged $51,194, over $20,000 (64.9%) a year more.[3]

The second most dramatic difference in average income was between those with a bachelor's degree with $51,940 and those with an advanced degree who made $72,824, roughly $21,000 (42.2%) more. The least significant difference was between those who had graduated from high school and those who had either some college or an associate degree. Here the difference was a mere $3,766 or 13.8%. The difference between those with a high school diploma ($30,000) and those who did not complete high school ($18,826) was $8,454 or 45%. Overall, the income in the United States for all sexes, races and levels of educational attainment was $36,308 annually.[3]

Even though African immigrants are claimed to have higher educational attainment rates than any other group, they were the hardest hit during the recession beginning in 2007.[26][21][27][28] This shows that race and/or ethnicity may play a role in income levels and job selection.[27]

| Criteria | Overall | Less than 9th grade | High school drop-out | High school graduate | Some college | Associate degree | Bachelor's degree | Master's degree | Professional degree | Doctorate degree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median individual income | Male, age 25+ | $51,297 | $30,018 | $30,065 | $40,901 | $46,851 | $51,734 | $67,399 | $90,011 | $122,239 | $101,126 |

| Female, age 25+ | $37,137 | $19,802 | $19,612 | $27,203 | $31,136 | $34,951 | $49,011 | $60,370 | $82,174 | $81,598 | |

| Median household income | $45,016 | $18,787 | $22,718 | $36,835 | $45,854 | $51,970 | $68,728 | $78,541 | $100,000 | $96,830 | |

SOURCE: US Census Bureau, 2018[29][30]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

The change in median personal and household income since 1991 also varied greatly with educational attainment. While both the overall median personal and household income increased since 1991, this increase did not take place on all levels of educational attainment. The overall income increased over the course of the 1990s, reaching its high in 1999, but has been decreasing ever since. In 1991 the median household income in the US was $40,873 in 2003 dollars, while the median household income in 2003 was $45,016. In 1999, however, the median household income was $46,236, 2.7% higher than today. While this trend held true for all levels of educational attainment the extent of chronicle fluctuations in income were greatly influenced by educational attainment.[29][30]

Overall, the median household and personal income decreased for those with more than a 9th grade education but less than a four-year college degree since 1991. In other words, the median household income decreased for households and individuals at the high school drop-outs and graduate, some-college, and an associate degree level. Income did, however, increase for those with a bachelor's degree or more. The following table shows the median household income according to the educational attainment of the householder. All incomes are adjusted for inflation and are in 2019 dollars. These data only apply to households whose householder is aged twenty-five or older. The highest and lowest points of the median household income are presented in bold face.[29][30]

| Year | Overall Median | Less than 9th grade | High school drop-out | High school graduate | Some college | Associate degree | Bachelor's degree | Bachelor's degree or more | Master's degree | Professional degree | Doctorate degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | $56,965 | $24,270 | $32,189 | $52,293 | $64,525 | $72,877 | $89,407 | $95,952 | $101,281 | $143,090 | $129,078 |

| 1993 | $56,197 | $24,320 | $31,388 | $50,142 | $61,533 | $69,155 | $89,941 | $98,040 | $105,422 | $153,161 | $130,601 |

| 1995 | $58,881 | $25,138 | $30,578 | $52,433 | $62,092 | $70,385 | $88,330 | $97,011 | $108,555 | $137,047 | $133,697 |

| 1997 | $60,849 | $24,762 | $31,629 | $53,821 | $63,756 | $72,110 | $94,082 | $100,844 | $108,529 | $146,948 | $138,988 |

| 1999 | $64,474 | $26,506 | $33,436 | $54,833 | $67,755 | $75,694 | $98,901 | $107,315 | $114,482 | (Not avail.) | $149,510 |

| 2001 | $63,100 | $26,229 | $33,656 | $52,190 | $66,311 | $74,058 | $97,223 | $104,633 | $114,212 | (Not avail.) | $134,339 |

| 2003 | $62,726 | $26,178 | $31,656 | $51,326 | $63,894 | $72,416 | $95,766 | $102,341 | $109,440 | (Not avail.) | $134,924 |

| 2005 | $62,618 | $26,540 | $32,381 | $50,118 | $63,363 | $71,795 | $95,042 | $101,282 | $106,327 | (Not avail.) | (Not avail.) |

| 2007 | $63,566 | $25,716 | $30,273 | $50,006 | $62,320 | $74,326 | $95,923 | $104,456 | $112,060 | (Not avail.) | (Not avail.) |

| 2009 | $60,884 | $25,843 | $30,583 | $47,358 | $57,828 | $67,833 | $90,205 | $98,810 | $109,486 | $147,857 | $144,380 |

| 2011 | $58,376 | $24,860 | $28,132 | $44,907 | $54,093 | $63,712 | $89,142 | $95,674 | $103,605 | $137,363 | $121,945 |

| 2013 | $58,515 | $26,596 | $28,220 | $44,741 | $54,615 | $61,762 | $87,416 | $94,989 | $105,473 | $143,612 | $133,324 |

| 2015 | $62,636 | $28,329 | $28,441 | $45,373 | $56,012 | $67,428 | $94,952 | $102,444 | $109,338 | $147,449 | $130,835 |

| 2017 | $65,314 | $27,729 | $31,392 | $46,901 | $57,949 | $67,022 | $95,712 | $104,316 | $112,878 | $145,040 | $146,126 |

| 2019 | $70,308 | $30,355 | $31,326 | $48,708 | $61,911 | $69,573 | $100,164 | $108,646 | $117,439 | $162,127 | $142,347 |

| Average | $61,694 | $26,225 | $31,019 | $49,677 | $61,197 | $70,010 | $93,480 | $101,117 | $109,235 | $146,369 | $136,161 |

SOURCE: US Census Bureau, 2020[32] Yellow indicates the year with the lowest median income while green indicates the year with the highest reported median income.

Among the races, educational attainment retains its dramatic effect on average income which varies significantly at each educational level. European Americans (White Americans) had the highest average income at every level of educational attainment. However, the proportion of those having college degrees is greater among Asian Americans than among non-Hispanic whites, and the overall highest average income is found among Asians. All races except Whites ranked last on at least one level with African Americans ranking last on the non-high school, high school and advanced degree level.[3]

Asians were second highest on the college graduate level and had the highest overall income among the general population. They also had the lowest average annual income for those with some college education or an associate degree. Racial income difference were also significant at every level of educational attainment with the largest racial inequality being between European and African Americans who did not complete high school and those with advanced college degrees.[3]

Overall, European Americans with an advanced degree had the highest average annual income with $74,122. Asian Americans had the second highest with $72,852. Hispanics and African Americans had the lowest annual incomes among those with advanced degrees averaging $67,679 and $59,944 annually. The largest racial inequity was between European Americans with a bachelor's degree who made $53,185 and Hispanics who made $12,263 or 29.9% less with an average annual income of $40,949.[3] However, Asian Americans as a whole earn more than any other race due to a greater percentage of them being educated overall, an example of Simpson's paradox.

Occupation

The rising demand for skilled workers indicates that job markets are able to accommodate an increasing number of highly qualified individuals, offering them improved employment opportunities. Conversely, adults with lower educational backgrounds face more daunting prospects in the labor market. They tend to earn lower wages and are at a higher risk of experiencing unemployment.[33] In the foreseeable future, their unemployment risk is expected to escalate further due to the likelihood of automation affecting many jobs that require lower qualifications.[34] Studies suggest that around 14% of current jobs could vanish due to automation within the next 15–20 years, while another 32% are anticipated to undergo significant changes as specific tasks become automated [35]

The educational attainment varied significantly among the different types of occupations. The professional/managerial fields were the only two occupational fields where college graduates with a bachelor's degree or higher represented the majority. Among professional occupations, 99.1% of the population graduated from high school, 90.2% had some college education or an associate degree and over two thirds, 68.2% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[3]

Business and managerial occupations were second with 97.8% having graduated from high school, 79.5% having some college or an associate degree and just over half, 53.4% having a bachelor's degree or higher. While nearly all employment fields feature a population where over 80% had graduated from high school with over a third having some college education or an associate degree, the fields relating to agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and transportation did not. These, often described as blue collar, fields featured a labor force where less than a tenth of the population had a bachelor's degree or higher, less than half had some college or an associate degree, and less than 80% had graduated from high school.[3]

Overall, the least educated occupational field was agriculture, ranking last on all educational levels. Here 55.4% had graduated from high school, roughly one fifth (20.8%) had some college education or an associate degree and 6.8% had a bachelor's degree or higher. While the largest occupational field, that consisting of professionals and relating occupations was also the largest field, the fields with lower educational attainment combined were larger than the professional and managerial fields combined. Overall, 38.02% were employed in the professional and managerial fields while 61.89% were employed in the other white and blue collar fields were those with a bachelor's degree or higher constituted less than a third of the work force.[3]

Religion

The Pew Research Center's 2014 Religious Landscape Study found educational attainment varied considerably across religious groups.[36] Hindu-Americans are the highest educated religious group in the United States.[37]

Membership in these religious groups can be highly correlated with demographic groups and geographic areas, so membership in a particular religion is not the only explanation for these differences, and vice versa.

Conservative Protestant Christian women who are more involved in their churches complete around one year more of schooling than those who are less involved. However, fundamentalist Christian students will likely have a harder time receiving higher education. This is due to the fact that fundamentalist Christians discourage college preparatory high school courses due to their emphasis on humanism, evolution, and tolerance. This in turn lowers their chances of getting into university, along with higher educational institutions sometimes discriminating against these fundamentalist groups.[38]

Using data from the 1987–88 National Survey of Families and Households,[39] Evelyn L. Lehrer found that the religion with the highest level of educational attainment was Jews, that Catholics and mainline protestants fell in the middle, and fundamentalists had the lowest levels of educational attainment.[40]

Michael A Kortt and Joseph Drew found that educational attainment in regards to religion can change with time. Specifically they found that:

- Christian Men in the Silent Generation had less educational attainment, but that their attainment increased for most denominations in future generations.

- However, Christian groups that are not part of the National Council of Churches (NCC) retained low educational attainment because of their more tightly held conservative beliefs.

- Additionally, educational attainment increased for Jewish males from Generation Y onward and from Generation X onward for non-Christian males of other religions.

- Anglican and non-NCC Women mirrored the educational attainment levels of non-NCC men.

- Jewish women had more educational attainment than non-religious women earlier than Jewish men did.

- Other non-Christian religious women also achieved higher educational attainment in proportion to non-religious women earlier than their male counterparts, but this did not continue in Generation Y.[41]

Geography

Educational attainment among the population aged 25 and above varied rather slightly with geography region. The population of the Northeastern United States, which had the smallest population of any region with thirty-six million residents, had the highest percentage of high-school and college graduates. The western United States had the highest percentage of those with some college or an associate degree and ranked second for college graduates. The South which had by far the largest population with roughly sixty-six million people had the lowest educational attainment at every level.[3]

The proportion of high school graduates was the largest in the Midwest while the proportion of those with some college or an associate degree was the second and that of those with a bachelor's degree or higher was the third largest of any region.

Social class and education

Educational attainment is one of the primary indicators of social class in the United States.[42] While the American social class system is a vaguely defined concept with many contradicting theories,[43][44] educational attainment emerges as one of the top assessments of social class. Not only is a high educational attainment a status symbol by itself, but it is also very closely related to the other two main indicators of social class: occupation and income. A graduate degree and the roughly seven to eight years of post-secondary education serve as the main requirement for entering the "professions" and becoming part of the professional middle class.[42]

Education is a major key in becoming a more privileged member of the American middle class.[42][44] Overall, educational attainment is the main entrance barrier into more privileged parts of the middle class as it is not only of high value but is also the requirement for becoming a professional and earning the corresponding income.[42] This corresponding income is typically significantly higher than that of someone without this higher level of educational attainment in the United States. Exceptions include some entrepreneurs who can rank anywhere in the class system but are usually not referred to as professional middle class unless they are of the professions.

In the United States, it is also important to differentiate between the statistical middle class, often defined as consisting of those who are neither rich nor poor, and the professional middle class. Recent research has shown that not only is the statistical middle of society (those with income roughly 80% to 120% of the national median or members of the mid-quintile) no longer able to afford the lifestyle indicative of the middle class,[45] but there also seems to be a widening income gap in between those who may be described as being middle class.

Education is not only the main requirement for becoming a member of the professional middle class, it is also key to a comfortable lifestyle and economic security.[42] Those in the statistical middle may have to fear lay-offs and cost-cutting downsizing as well as out-sourcing, while some of those in the professional middle class are less subject to economic fluctuations and are more likely to enjoy upper-middle range incomes even in the face of recessions. Increasingly however even the professional middle class is facing lay-offs and job elimination due to downsizing and replacement of full-time workers with part-time workers—this is particularly evident in colleges and universities where, by 2009, half of the faculty were part-time; another 25% were full-time but with short-term contracts, thus showing that advanced education is not necessarily associated with high salaries and economic stability.[46]

Educational attainment in social theory

Bourdieu and cultural capital

Many scholars have studied educational attainment in the US as a form of social reproduction and stratification. In 1977, Pierre Bourdieu presented the idea that education leads to social reproduction and a stratified society by honoring the cultural capital of elite classes. Students who possess the valued cultural capital, according to Bourdieu, are rewarded with high academic achievement.[47]

When elite class members enter the workforce, they are channeled into high paying jobs and powerful positions within society, while those who did not achieve the same level of academic success fall into subordinate occupations and status levels. By rewarding the desired cultural capital with high academic achievement, upper classes are able and prepared to reach higher levels of educational attainment. Members of the working class, on the other hand, are not rewarded for their cultural capital in schools, and are instead socialized for working class jobs.

Lareau and concerted cultivation

Annette Lareau also addresses the factors that lead to social stratification in educational attainment. Lareau's idea of concerted cultivation refers to an active involvement of parents in a child's learning and development experiences by creating and controlling organized activities for their children. According to Lareau, middle-class parents engage in concerted cultivation to teach their children, while lower- and working-class parents do not. Laureau further explains that schools firmly encourage and expect parents to use concerted cultivation as a child-rearing strategy.[48]

The child-rearing practices of lower- and working-class families thus do not comply with the standards of educational institutions. As a result, lower- and working-class students develop a sense of "distance, distrust, and constraint" in educational institutions, while children of middle-class families gain a sense of entitlement. These differences in child-rearing practices lead to children of lower- and working-class families to lack the necessary life skills that the children of the middle class possess, further isolating them from educational opportunities. In the United States, education attainment typically is viewed as a sign of social status.

Collins and credentialism

Randall Collins contributed the idea of credentialism to the study of class-based differences in educational attainment. Collins maintains that public schools are socializing institutions that teach and reward middle-class values of competition and achievement. In this view, elites are selectively separated from other students and placed into prestigious schools and colleges, where they are trained to hold positions of power.[49]

See also

- American middle class

- Education in the United States

- Household income in the United States

- Literacy in the United States

- Poverty in the United States

- List of U.S. States by Education attainment

- Racial achievement gap in the United States

General:

References

- ^ Ryan, Camille; Siebens, Julie (March 2016). "Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Educational attainment". National Center for Education Statistics. Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "US Census Bureau report on educational attainment in the United States, 2003" (PDF). Retrieved July 31, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "A Half-Century Of Learning: Historical Census Statistics On Educational Attainment in the United States, 1940 to 2000". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. April 2006.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Phillips, Matt (October 23, 2014). "Indians in the US make the most because they studied the most". Quartz. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Note that these add up to more than 100% because they are cumulative; e.g. it is assumed that all people with doctorates also have undergraduate and high school degrees, and are thus counted twice in the "lower" categories. Age 25 is used rather than age 18 because there are few people aged 18 or over with advanced degrees. "Educational Attainment in the United States: 2018". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 23, 2018. Percentages are calculated based on census data by counting people that had attained that level or higher.

- ^ a b Kafir, Krista (April 2007). "Taking the Boy Crisis in Education Seriously: How School Choice can Boost Achievement Among Boys and Girls." Independent Women's Forum.

- ^ "Education and earnings".

- ^ a b c Perie, M. (2005). NAEP 2004 Trends in Academic Progress. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

- ^ a b Persky, H. (2003). The Nation's Report Card: Writing 2002. US Department of Education.

- ^ a b Salahu-Din, Debra (2008). The Nation's Report Card: Writing 2007. US Department of Education.

- ^ a b c "Historical summary of faculty, students, degrees, and finances in degree-granting institutions: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2015–16". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "Percentage of high school dropouts among persons 16 through 24 years old (status dropout rate), by sex and race/ethnicity: Selected years, 1960 through 2016". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ Mead, Sara. (2006). The Evidence Suggests Otherwise: The Truth About Boys and Girls. Washington: Education Sector.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement 2007.

- ^ "Degrees conferred by degree-granting institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2016–17". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b "Race gaps in SAT scores highlight inequality and hinder upward mobility". February 2017.

- ^ Miller LS. 1995. An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ David Shortell and Taylor Romine (August 13, 2020). "Justice Department accuses Yale of discriminating against Asian American and white applicants". CNN. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "African Immigrants are the Most Educated". Africaresource.com. April 28, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b "Migration Information Source - African Immigrants in the United States". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "AAME". Inmotionaame.org. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Affirmative Action Minorities - Affirmative Action College Admissions". Racerelations.about.com. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ (Logan & Deane, 2003; Williams, 2005; The Economist, 1996; Arthur, 2000; Selassie, 1998).

- ^ "AAME : image". Inmotionaame.org. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Sub-Saharan African immigrants arrive with the most education but struggle with underemployment". FSRN Radio News. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Bradford, Harry (August 3, 2011). "Foreign-Born Blacks Hit Hardest Of All Immigrant Groups By Jobs Crisis". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Migration Information Source - Characteristics of the African Born in the United States". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c Hannula, Alec. "Educational attainment and median household income 2018 Data Men". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 3, 2006. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hannula, Alec. "Personal income and educational attainment, US Census Bureau Women". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 7, 2006. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "US Census table H-14". Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "Table H-13. Educational Attainment of Householder--Households with Householder 25 Years Old and Over by Median and Mean Income: 1991 to 2019". Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Home".

- ^ Arntz, Melanie; Gregory, Terry; Zierahn, Ulrich (2016). "The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries". OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en.

- ^ OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. February 25, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Caryle. "The most and least educated U.S. religious groups".

- ^ "Hindus Most Educated Religious Community in US: Report". The Quint. January 9, 2019. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Lehrer, Evelyn. "Religiosity as a Determinant of Educational Attainment: The Case of Conservative Protestant Women in the United States". ebscohost. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Bumpass, Larry L.; Sweet, James A.; Call, Vaughn R.A. "National Survey of Families and Households, Wave 1: 1987-1988, [United States] (ICPSR 6041)". ICPSR. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Lehrer, Evelyn L. "Religion as a Determinant of Educational Attainment: An Economic Perspective" (PDF). Science direct assets. Academic press. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Kortt, Michael A; Drew, Joseph. "Does religion influence educational attainment?". Taylor and Francis online. Religion and Education. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Ehrenreich, Barbara (1989). Fear of Falling, The Inner Life of the Middle Class. New York, NY: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-097333-1.

- ^ "Middle class according to The Drum Major Institute for public policy". PBS. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ a b Fussel, Paul (1983). Class, A Guide through the American status system. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN 0-671-79225-3.

- ^ "Middle income can't buy Middle class lifestyle". Archived from the original on December 30, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ James Monks. "Who are the Part-time Faculty?" Academe, July–August 2009. http://www.aaup.org/article/who-are-part-time-faculty#.UsU90fQW0oo

- ^ Bourdieu, P. (1977) Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In: Karabel, J., & Halsey, A. H. (eds.) Power and Ideology in Education. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 487-511.

- ^ Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal Childhoods; Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23950-4.

- ^ Collins, R (1979). The Credential Society; An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification. New York, NY: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-181360-6.

Further reading

- Sunny Decker (1969), An Empty Spoon, New York: Harper & Row.

- James Herndon (1968/1969), The Way It Spozed to Be, reprint, New York: Bantam.

- James Herndon (1971/1997), How to Survive in Your Native Land, reprint, Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

- James Herndon (1985), Notes from a Schoolteacher, New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Holly Yettick and Sterling C. Lloyd (2015), "Graduation Rate Hits High, But Some Groups Lag," Education Week.

External links

- Educational Attainment in the United States: 2003, U.S. Census Bureau

- The Big Payoff: Educational Attainment and Synthetic Estimates of Work-Life Earnings, U.S. Census Bureau

- Map: Graduation Rate by State, Student Group, Education Week