Tibicos

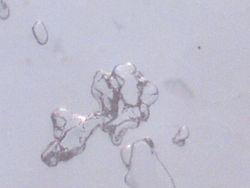

Tibicos, or water kefir, is a traditional fermented drink made with water and a water kefir grains held in a polysaccharide biofilm matrix created by the bacteria. It is sometimes consumed as an alternative to milk-based probiotic drinks or tea-cultured products such as kombucha. Water kefir is typically made as a probiotic homebrew beverage. The finished product, if bottled, will produce a carbonated beverage.

Cultures

Tibicos cultures are found around the world, with no two being exactly the same; but typical tibicos have a mix of Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Pediococcus and Leuconostoc bacteria, with yeasts from Saccharomyces, Candida, Kloeckera and possibly others. Lactobacillus brevis bacteria has been identified as the species responsible for the production of the dextran polysaccharide that forms the "grains".[1][2]

As with milk kefir "grains", the microbes present in tibicos act in symbiosis to maintain a stable culture. Tibicos can do this in many different sugary liquids like coconut water or straight fruit juice yet the most common one is definitely sugar and water,(it's important to use organic cane sugar or unrefined sugar, which will benefit the fermentation)[citation needed] feeding off the sugar to produce lactic acid, alcohol (ethanol), and carbon dioxide gas, which carbonates the drink.

Origin

The origin of tibicos grains is not known exactly.[3] The grains called ginger beer plant, which according to Martinus Beijerinck[4] were brought by the British soldiers while returning to their country from the Crimean War in 1855 (although this was dismissed as an unsubstantiated myth by Harry Marshall Ward as early as 1892 [5] and its real origins remain a mystery), were defined by Harry Marshall Ward as "beverage containing a symbiotic mixture of yeast and bacteria, and containing sufficient amounts of nitrogenous organic matter and beet sugar or cane sugar in its aqueous solution".[5] This description is probably the first published account of the water kefir culture.[6] As a different theory, Lutz (1899) reported "Tibi grains" which were plucked from the leaves of a Mexican cactus (Opuntia).[7][2] These granules then could be reconstituted in a sugar-water solution for propagating the tibicos grains.[3] Another study found a similar tibicos culture made from bacteria cultured from known stocks with similar properties.[8]

Tibicos are also known as tibi, water kefir grains, sugar kefir grains, Japanese water crystals and California bees, and in older literature as bébées, African bees, Australian bees, ginger bees, vinegar bees, bees, Japanese beer seeds, beer seeds, beer plant, ale nuts, eternity grains,[9] and Balm of Gilead.[3][10] Pidoux in 1898 also identified the sugary kefir grains with the ginger beer plant.[2] Different ingredients or hygienic conditions might also change the bacteriological composition possibly leading to the different names found in scientific literature.

Tibicos are used to brew a variety of tepache known as tepache de tibicos.[11] The ginger beer plant is also a form of tibicos. Kebler attests that they were used in Kentucky circa 1859 to brew a "home drink" and were referred to as "Japanese beer seeds."[10]

Preparation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

The basic preparation method is for tibicos to be added to a sugary liquid and fermented 24 to 48 hours. The water is kept at a room temperature range of 20–30 °C (70–85 °F). If the temperature is towards the upper end of this range, the fermentation period is shortened.[12] A typical recipe might contain the tibicos culture, a citrus fruit, dried fruit, and water.[13] Some ingredients will inhibit fermentation, such as chlorine in tap water or preservatives in dried fruit (sulfites). The fruits used are changed and mixed to create different flavors.[14]

Additional precautions are taken to keep the cultures healthy. The use of reactive metals such as aluminium, copper, or zinc are minimised. The acidity of the solution will react with the metals forming metal ions, which could be potentially damaging to the culture. Instead, plastic, lead-free ceramic, or glass containers are commonly used. It is recommended to culture grains in a glass jar and use clean plastic or silicone utensils when handling the grains.

Researchers demonstrated antimicrobial activity during tibicos fermentation, using tibicos grains to ferment different sugar sources, namely, molasses, demerara sugar, and brown sugar. Brown sugar promoted the greatest antimicrobial activities, against the microorganisms Candida albicans, Salmonella typhi, Shigella sonnei, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.[15]

For tibicos grains to grow, a certain water buffer capacity and/or calcium concentration are required.[16] If necessary, buffer capacity can be improved by adding some hydrogen carbonate-rich mineral water.[17]

See also

External links

- An alternative source of probiotics: Water kefir

- Water Kefir: A Review of its Microbiological Profile, Antioxidant Potential and Sensory Quality

- An update on water kefir: Microbiology, composition and production

- Development of new non-dairy beverages from Mediterranean fruit juices fermented with water kefir microorganisms

- Characterization of kefir-like beverages produced from vegetable juice

- Functional Exploitation of Carob, Oat Flour, and Whey Permeate as Substrates for a Novel Kefir-Like Fermented Beverage: An Optimized Formulation

- Development, Characterization, and Bioactivity of Non-Dairy Kefir-Like Fermented Beverage Based on Flaxseed Oil Cake

- Antioxidant potency of water kefir

- Water Kefir and Derived Pasteurized Beverages Modulate Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Permeability and Cytokine Production In Vitro

- Study of anti-inflammatory activity of Tibetan mushroom, a symbiotic culture of bacteria and fungi encapsulated into a polysaccharide matrix

- Probiotic Potential of Lactobacillus paracasei CT12 Isolated from Water Kefir Grains (Tibicos)

- Evaluation of Anti-Hyperglycemic and Anti-Hyperlipidemic Activities of Water Kefir as Probiotic on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Wistar Rats

- Water kefir: Factors affecting grain growth and health-promoting properties of the fermented beverage

- Anti-Inflammatory and Cicatrizing Activities of a Carbohydrate Fraction Isolated from Sugary Kefir

- Antimicrobial Activity of Broth Fermented with Kefir Grains

- Microbial Species Diversity, Community Dynamics, and Metabolite Kinetics of Water Kefir Fermentation

- The Buffer Capacity and Calcium Concentration of Water Influence the Microbial Species Diversity, Grain Growth, and Metabolite Production During Water Kefir Fermentation

- Pollution Abatement of Heavy Metals in Different Conditions by Water Kefir Grains as a Protective Tool against Toxicity

- Quantitative insights on the interaction between metal ions and water kefir grains: kinetics studies and EPR investigations

References

- ^ Horisberger, M.; Bauer, H.; Bauer, Heinz (December 1980). "The structural organization of the Tibi grain as revealed by light, scanning and transmission microscopy". Archives of Microbiology. 128 (2): 157–161. Bibcode:1980ArMic.128..157M. doi:10.1007/BF00406153. S2CID 30407268.

- ^ a b c Pidoux, M. (June 1989). "The microbial flora of sugary kefir grain (the gingerbeer plant): biosynthesis of the grain from Lactobacillus hilgardii producing a polysaccharide gel". World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 5 (2): 223–38. doi:10.1007/BF01741847. S2CID 83381986.

- ^ a b c Laureys, David; De Vuyst, Luc (April 2014). "Microbial Species Diversity, Community Dynamics, and Metabolite Kinetics of Water Kefir Fermentation". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 80 (8): 2564–2572. Bibcode:2014ApEnM..80.2564L. doi:10.1128/AEM.03978-13. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 3993195. PMID 24532061.

- ^ Fiorda, Fernanda Assumpção; de Melo Pereira, Gilberto Vinicius; Thomaz-Soccol, Vanete; Rakshit, Sudip Kumar; Pagnoncelli, Maria Giovana Binder; de Souza Vandenberghe, Luciana Porto; Soccol, Carlos Ricardo (September 2017). "Microbiological, biochemical, and functional aspects of sugary kefir fermentation - A review". Food Microbiology. 66: 86–95. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2017.04.004. PMID 28576377.

- ^ a b Ward, Harry Marshall (1 January 1892). "The ginger-beer plant, and the organisms composing it: A contribution to the study of fermentation-yeasts and bacteria". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 183: 125–197. doi:10.1098/rstb.1892.0006.

- ^ Cufaoglu, Gizem; Erdinc, Ayse Nur (8 January 2023). "An alternative source of probiotics: Water kefir". Food Frontiers. 4: 21–31. doi:10.1002/fft2.200. S2CID 255676470.

- ^ Lutz, L. (1899). "Recherches biologiques sur la constitution du Tibi". Bull. Soc. Mycol. France. 15: 68–72.

- ^ Stacey, M.; Youd, F. R. (November 1938). "A note on the dextran produced from sucrose by Betacoccus arabinosaceous haemolyticus". Biochem. J. 32 (11): 1943–1945. doi:10.1042/bj0321943. PMC 1264277. PMID 16746830.

- ^ Sopp, J.O. (1917). Hjemmelagning av øl og vin. Kristiania, Norway: Norli. p. 83.

- ^ a b Kebler, L. F. (June 1921). "California bees". J. Pharm. Sci. 10 (12): 939–943. doi:10.1002/jps.3080101206.

- ^ Romero-Luna, Haydee Eliza; Hernández-Sánchez, Humberto; Dávila-Ortiz, Gloria (3 August 2017). "Traditional fermented beverages from Mexico as a potential probiotic source". Annals of Microbiology. 67 (9): 577–586. doi:10.1007/s13213-017-1290-2. S2CID 256073930.

- ^ "Encouraging Water Kefir Grains to Multiply: 7 Tips for Happy & Healthy Grains". 23 June 2022.

- ^ Gross, Ivo (11 July 2023). "The ultimate guide to water kefir". Letsgotomato.com. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "How to Brew Water Kefir: Your #1 Guide to DIY Water Kefir". 8 February 2021.

- ^ Silva, Karoline; Rodrigues, Sheila; Filho, Lauro Xavier; Lima, Alvaro S. (29 July 2008). "Antimicrobial Activity of Broth Fermented with Kefir Grains". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 152 (2): 316–325. doi:10.1007/s12010-008-8303-3. PMID 18663417. S2CID 19989453.

- ^ Laureys, David; Aerts, Maarten; Vandamme, Peter; De Vuyst, Luc (13 December 2019). "The Buffer Capacity and Calcium Concentration of Water Influence the Microbial Species Diversity, Grain Growth, and Metabolite Production During Water Kefir Fermentation". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 2876. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02876. PMC 6923659. PMID 31921054.

- ^ Beer, Andre-Michael; Uebelhack, Ralf; Pohl, Ute (15 February 2016). "Efficacy and tolerability of hydrogen carbonate-rich water for heartburn". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 7 (1): 171–180. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v7.i1.171. PMC 4753184. PMID 26909240.