Queenstown Massacre

On 17 November 1985, 2000 residents from Mlungisi township in Queenstown, Eastern Cape, gathered in Nonzwakazi Methodist Church to hear back from the Local Residents Association, who, in early November, had met with the Department of Education and Training, the Queenstown municipality, the Eastern Cape Development Board, and the Queenstown Chamber of Commerce to discuss the end of the consumer boycott. The meeting was short-lived as members of the Queenstown branch of the South African Police stormed into the meeting and opened fire on the residents. In the ensuing conflict between police and residents, 14 people were shot dead and 22 were injured. This incident is known as the 1985 Queenstown Massacre.[1][2]

Background

There had been no major political conflicts in Queenstown and the surrounding areas from the 1960s until the mid-1970s except for the forced removals and the incorporation of areas into the neighbouring Ciskei and Transkei homelands.[1]

In the 1980s, the South African apartheid government led by PW Botha implemented system reforms aimed at creating divisions, and thus weakening the resistance of the people. One of these was by building a buffer middle class. Buffer middle class areas meant that infrastructural development was introduced in selective black townships. Some residents had better facilities than others, which created resentment between them. Botha's reform saw the creation of local black councils which fell under the national, white-run state administration (the "Bantu Administration Board"), which would continue to control the power and resources available to the township authorities.[2]

The homes of people who supported and benefited from Botha's reforms, government buildings and beer halls, which were sponsored by the government, were attacked. At the same time organisations such as the newly formed United Democratic Front were applying pressure on the government through civic associations.[3] Events such as the Langa Massacre in Uitenhage, the consumer boycott in Port Elizabeth, the killing of The Cradock Four and the shootings in Aliwal North created an atmosphere of unrest in the Eastern Cape townships.[1]

In Mlungisi township, Queenstown, the major grievances of the people were household evictions and the lack of a basic service infrastructure. In an article in the Daily Maverick of 19 November 2015 titled "Your bullets will not stop us: A recollection of the 1985 Queenstown massacre" Mlungisi community resident Ntombizodwa Martha Kamati: "The main matters were absence of toilets, the sharing of public toilets. This was a major issue which made people to be annoyed. And there was this lodger's permit that people disliked, because you would be arrested [at] five-o-clock in the morning by the police, and then they would move with you in their van up and down, taking people from all over the location until it was at eight when they opened their office."[2]

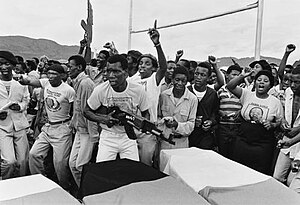

To voice out their grievances, the community of Mlungisi and surrounding areas, such as Ezibeleni and Whittlesea, under the influence of the United Democratic Front, organised a consumer boycott, which began in August 1985, wherein they placed pressure on the local business community. As part of the consumer boycott, black communities around Queenstown stopped buying from most white businesses in the area. Only white businesses that were seen as progressive received support.[2]

Tension between the coloured and African communities followed the enforcement of the consumer boycott and at least one coloured man was necklaced (burnt with a tyre around his neck). This led to the formation of a coloured vigilante group, supported by the local SAP and SADF, which attacked the black people in Mlungisi. Black schools were also out on boycott since the assassination of The Cradock Four in June.[citation needed]

In September, the brother of a suspected apartheid informer was necklaced in Queenstown's Mlungisi township.[1]

In early November 1985, the Local Residents Association, the Department of Education and Training, the Queenstown municipality, the East Cape Development Board, and the Queenstown Chamber of Commerce held a meeting with the aim of ending the boycott.[2]

The Massacre

2000 people gathered at Nonzwakazi Methodist Church in Mlungisi to get feedback on the negotiations from Local Residence Association on 17 November 1985.

Narrating the events of the day in the article titled "Your bullets will not stop us: A recollection of the 1985 Queenstown massacre" in "The Daily Maverick" of 19 November 2015, Daniel Lolwana, Chairperson of the Residents Association who was addressing the meeting, said: "I noticed an old man, Lizo Ngcana, being dragged inside, bleeding. And then he fell just where we were standing, it was right in front of the pulpit. Then, as I said there was pandemonium, the hall was filled with teargas and there was shooting all over. You could hear the shots. Now, because I worried about this man, when the casspirs from this side shifted over to the side of the Moravian Church, I ran quickly to the second house there to utilise a telephone."[2]

14 people lost their lives and 22 were wounded as a result of being shot with live ammunition by the police. On 13 December, all the victims of the massacre were buried at a mass funeral in Mlungisi township.[citation needed]

Aftermath

In response to questions in parliament over a year later, the then Minister of Justice, Mr Kobie Coetsee, said that an inquest into nine deaths from that incident had found that nobody was criminally liable. In 1996, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found the SADF and SAP guilty and accountable for the death of 14 people at Nonzwakazi Methodist Church in Mlungisi township.[1]

See also

- List of massacres in South Africa

- Marikana massacre

- Sharpeville massacre

- Bisho massacre

- Langa Massacre

References

- ^ a b c d e "Queenstown massacre: November 1985". South African History Online. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Cawe, Ayabonga. "Your bullets will not stop us: A recollection of the 1985 Queenstown massacre". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Against Botha's Deal". South African History Online. Retrieved 9 November 2017.