Military of the Warring States

The military of the Warring States refers primarily to the military apparatuses of the Seven Warring States which fought from around 475 BC to 221 BC when the state of Qin conquered the other six states, forming China's first imperial dynasty, the Qin dynasty.

Wu Qi (440–381 BC)

Wu Qi was a general born in the state of Wei who went on to serve in the state of Chu. He is traditionally credited with the authorship of the Wuzi, one of the Seven Military Classics, in which he described the military merits of six of the Warring States.

The nature of Qin's troops is to disperse so that each unit fights their own respective battles... The people of Qin are ferocious by nature and their terrain is treacherous. The government's decrees are strict and impartial. The rewards and punishments are clear. Qin soldiers are brave and high in morale so that they are able to scatter and engage in individual combat. To strike at Qin's army, we must entice various groups with small benefits; the greedy will abandon their general to give chase. We can then capitalize on this opportunity by hunting each group down individually and then capturing the generals that have been isolated. Finally, we must array our army to ambush their commander.[1][2]

— Wuzi, Master Wu

- Soldiers sometimes discarded armour in favor of fast charges.

- According to Xun Qing (c. 314 – c. 217 BC), the people of Qin were "simple and unsophisticated", and their officials performed their tasks conscientiously without displaying partiality or forming cliques.

- Almost complete absence of literati.

Although Qi's troops are numerous, their organization is unstable...The people of Qi are by nature unyielding and their country prosperous, but the ruler and officials are arrogant and care nothing for the people. The state's policies are not uniform and not strictly enforced. Salaries and wages are unfair and unevenly distributed, causing disharmony and disunity. Qi's army is arrayed with their heaviest hitters at the front while the rest follow behind, so that even when their forces appear mighty, they are in reality fragile. To defeat them, we should divide our army into three columns and have two attack the left and right flanks of Qi's army. Once their battle formations are thrown into disarray, the central column should be in position to attack and victory will follow.[3][4]

— Wuzi, Master Wu

Chu's military formations are complete but cannot be maintained for long... The Chu people are soft and weak. Their lands stretch far and wide, and the government cannot effectively administer the expanse. Their troops are weary and although their formations are well-ordered, they do not have the resources to maintain their positions for long. To defeat them, we must strike swiftly, unexpectedly and retreat quickly before they can counter attack. This will create unease in their weary soldiers and reduce their fighting spirit. Thus, with persistence, their army can be defeated.[5][6]

— Wuzi, Master Wu

- Invented the repeating crossbow.

- Early adopter of iron and steel weapons.

- Wore shark skin and rhinoceros hide armour even until its demise

- Elite armoured crossbowmen capable of marching 160 km "without resting".

Yan's defensive formations are solid but lack flexibility... The Yan are a sincere and straightforward people. They act prudently, love courage and esteem righteousness while rarely employing deception. Thus they excel in defensive positions, but are immobile and inflexible. To defeat them, immediately apply pressure with small attacks and retreat rapidly. When they turn to face our attacks, we should keep a distance. Attack the rear as well where and when they least expect it. When they withdraw to face another threat, chase them. This will confuse their generals and create anxiety in their ranks. If we avoid conflict against their strong points and use our armored chariots to set ambushes, we can capture their generals and insure victory.[7][8]

— Wuzi, Master Wu

- Early adopter of iron and steel weapons.

The two states of Han and Zhao train their troops rigorously but have difficulty in applying their skills to the battlefield... Han and Zhao are states of the Central Plain. Theirs are a gentle people, weary from war and experienced in arms, but have little regard for their generals. The soldiers' salaries are meager and their officers have no strong commitment to their countries. Although their troops are experienced, they cannot be expected to fight to the death. To defeat them, we must concentrate large numbers of troops in our attacks to present them with certain peril. When they counterattack, we must be prepared to defend our positions vigorously and make them pay dearly. When they retreat, we must pursue and give them no rest. This will grind them down.[9][10]

— Wuzi, Master Wu

- Han made the best weapons.

- Han was an early adopter of iron and steel weapons.

- Han soldiers made use of face masks.

- Zhao was an early adopter of mounted archers and crossbowmen.

Wu Qi did not mention the military merits of Wei.

- Elite armoured soldiers capable of marching 40–50 km in one day while equipped with heavy armour, a helmet, a halberd or pike, swords, a crossbow with 50 bolts, and three days of rations.[11]

-

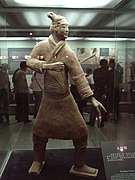

Qin general, front

-

Qin general, back

-

Qin charioteer, front

-

Qin charioteer, back

-

Qin cavalryman, front

-

Qin cavalryman, back

Other states

- Earliest archaeological evidence of crossbows.[citation needed]

History

Technically speaking, the Warring States period overlaps with the Eastern Zhou dynasty, but by this point, the Zhou kings had become politically irrelevant. Their feudal vassals had adopted the title of king and were functionally independent of any other power.[12]

Periodization

There is no agreed upon starting point for the Warring States period. According to one definition, it began in 481 BC when the House of Tian eliminated the House of Jiang and usurped the throne of Qi. Another defines the start as the Battle of Jinyang in 453 BC when the viscounts of Han (state), Zhao (state), and Wei (state) eliminated the Lord of Zhi, thereby becoming the most powerful families in the state of Jin. Other starting points for the Warring States period include 403 BC, when King Weilie of Zhou bestowed upon the viscounts of Han, Zhao, and Wei the title of marquis, or the Partition of Jin in 376 BC, when the Three Jin divided the territory of Jin among themselves, forming their own states.[13]

Partition of Jin (453–376 BC)

In the beginning of the 5th century BC, the state of Jin was dominated by five noble houses. In 453 BC, the three houses of Han, Zhao, and Wei defeated their rivals at the Battle of Jinyang and began the tripartite division of the old state of Jin. In 424 BC, they mutually recognized each other's independence; however, it was not until 403 BC when King Weilie of Zhou recognized this political reality and bestowed upon them the title of marquis. In 376 BC, they formally divided the territory of Jin between themselves.[14]

Partition of Zhou (441 BC)

In 441, King Ai of Zhou was killed by his brother Shuxi, who became King Si of Zhou. King Si was killed five months later by his brother Wei, who became King Kao of Zhou. Fearing another usurpation, King Kao decided to split the territory of Zhou in half, with his brother, Prince Jie, ruling as the Duke Huan of Henan in Wangcheng, while he himself resided in Gong or Chengzhou. During the reign of King Xian of Zhou (r. 369-320 BC), Duke Hui declared independence for West Zhou, formally dividing Zhou into two territories. This bipartite situation persisted until 314, when King Nan of Zhou moved back to Wangcheng in West Zhou. In 256, the state of Qin annexed West Zhou and demoted King Nan to a duke. The remnants of West Zhou fled to East Zhou where they proclaimed Duke Wen as king. East Zhou's army was defeated by the Qin in 251 and was annexed two years later, ending the Zhou dynasty.[15][16]

Rise and decline of Wei (424–341 BC)

Under the reign of Marquess Wen of Wei and Marquess Wu of Wei, the state of Wei expanded in all directions. In 408, Wei conquered Zhongshan and its generals Li Kui and Wu Qi dealt several defeats to the forces of Qin. In 405, Zhao, Wei, and Han defeated the army of Qi, capturing thousands of chariots and soldiers. In 402, the Three Jins defeated a Chu army at Shengqiu and again in 391 destroyed a Chu army at Daliang. Although a succession struggle in Wei allowed Zhongshan to regain its independence in 380, Wei had become the strongest power in China, attacking the states of Song, Wey, Han, and Zhao. The Qin returned in 366 and defeated Wei and Han at the Battle of Luoyin. Han and Zhao had a falling out, resulting in their defeat by Wei forces under Gongshu Cuo at the Battle of River Kuai. In 353, Wei sacked the capital of Zhao, Handan, but was then defeated in battle at Guiling by the state of Qi.[17]

In 344, Marquis Hui of Wei invited other rulers to Mengjin under the pretense of paying tribute to the Zhou king. At the same time he proclaimed himself king. Wei's power did not last much longer. In 342, its army was ambushed at the Battle of Maling (Fanxian) by the army of Qi led by Tian Ji and Sun Bin. Soon after, Wei also lost its advantage in the west against a resurgent Qin under Shang Yang, who saw the return of previously lost territories and even forced Wei to shift its capital further east to Daliang.[18]

Qin ascendant (356–257 BC)

Under the reign of Duke Xiao of Qin (r. 361–338 BC) and the implementation of Shang Yang's reforms, Qin became a major military power in China. Shang Yang's reforms emphasized agriculture and war over all other occupations. In Shang Yang's eyes, only tillers and soldiers were deserving of ranks and offices, while merchants, artisans, and intellectuals should be barred from official careers.

The means whereby a ruler of men encourages the people are office and rank; the means whereby a country is made prosperous are agriculture and war. Now those who seek office and rank, never do so by means of agriculture and war, but by artful words and empty doctrines. That is called "wearying the people". The country of those who weary their people will certainly have no strength, and the country of those who have no strength will certainly be dismembered.[19]

After Wei's disastrous defeat at the Battle of Maling in 342, Shang Yang invited the Wei general Gongzi Ang for a meeting, during which he arrested Gongzi Ang and destroyed his army. Qin went on to defeat Wei again in 339 at the Battle of Anmen and in 333 at the Battle of Diaoyin.[20]

In 325, Duke Huiwen (r. 338–311 BC) declared himself king. Supreme commander Gongsun Yan defected to Wei and opposed Qin's rise by forging an alliance with Zhao, Han, Yan, and Chu. Together they attacked Qin in 318, but were defeated at the Battle of Xiuyu. Qin came to be known as the "wolf" from the west, carrying out annual attacks on neighboring peoples. In 316, Qin took advantage of a quarrel between the states of Ba, Shu, and Ju to their southwest, and annexed them, although normal commanderies would not be instituted until 285. In 312, Qin defeated the Chu army at Huayang and Lantian. In 308, Qin killed 60,000 Han troops. Chu lost another battle in 300, forcing King Huai of Chu to visit Qin for negotiations. He was imprisoned and died in captivity. Only a new alliance between Qi, Wei, and Han initiated by Lord Mengchang was able to drive Qin back to the eastern border at Hangu Pass.[21]

The Qin returned again in 293 under the leadership of Bai Qi. His troops defeated the armies of Han and Wei at the Battle of Yique, allegedly killing 260,000 enemy soldiers. In 280, Qin forces advanced on Chu in three directions. In 278, Bai Qi took the city of Yan from Chu and followed that up a year later by taking Ying, the Chu capital. In 275, Marquis Rang led Qin forces to victory against Han, Wei, and Qi, killing 40,000 troops. In 272, Bai Qi defeated Zhao and Wei at Huayang, allegedly killing 150,000 enemy soldiers. At the same time Qin forces annexed the Yiqu on their northwestern border, transforming their territory into the commanderies of Longxi, Beidi, and Shang. However, in 270, Qin forces were defeated by the Zhao General Lian Po at Eyu, halting their advance for the moment.[22]

In 265, Qin invaded Han and cut off 17 districts from Shangdang. The king of Han decided to cede those to Qin, but the local governor refused and instead defected to Zhao.[23]

In 260, Qin and Zhao stood deadlocked in a stalemate at Changping. In 259, King Xiaocheng of Zhao became impatient was persuaded that his general Lian Po was avoiding combat. He recalled Lian Po and replaced him with a less experienced commander, Zhao Kuo, who immediately ordered his forces to attack the Qin. Bai Qi cut off the enemy supply line and surrounded them. After 46 days, the Zhao army was on the brink of starvation. Zhao Kuo made a final attempt to break out but was killed in the assault. The Battle of Changping ended with the surrender of Zhao forces, however the Qin buried them alive, reportedly killing 400,000 enemy soldiers. Zhao never recovered this loss. Due to Bai Qi's immense success, high minister Fan Ju grew jealous and persuaded the king to slow down the pace of military operations. Two years later, the Qin army was defeated by relief forces from Wei and Chu at the siege of Handan, the capital of Zhao. Bai Qi feigned sickness and refused to lead the siege due to Fan Ju's machinations at court. In response, Fan Ju suggested demoting Bai Qi to a common soldier. Bai Qi committed suicide while on his way back to the capital.[24]

Dukes to kings (344–325 BC)

In 344, Marquis Hui of Wei became the first ruler of the Warring States to proclaim himself king. However, it was not until 325, when Duke Huiwen of Qin declared himself king, that the other rulers joined in unison and also declared themselves kings.[25]

Rise and fall of Song (318–286 BC)

In 318, Lord Yan of Song declared himself King Kang of Song. King Kang embarked on campaigns of conquest against its neighbors, conquering Xue and Teng in 297, and was even able to defeat the forces of Qi, Chu, and Wei in battle. In 286, these three states formed an alliance and defeated Song, splitting its territory between themselves.[26]

Yan-Qi conflict (314–281 BC)

In 314, a succession in Yan incited King Xuan of Qi to invade Yan. However, Qi was ultimately forced to withdraw two years later. In 284, Yan successfully invaded Qi and annexed all its territory except for Ju and Jimo. In 281, Qi counterattacked by driving cows with burning tails into the Yan camp and defeated them.[27]

Zhao adopts cavalry (306 BC)

In the mid to late 4th century BC, the state of Zhao adopted cavalry tactics from the northern nomads. Using their new cavalry forces, Zhao conquered Zhongshan in 306.[28] Zhao general Li Mu went on to successfully defeat the Xiongnu several times after he took control of Zhao's frontier forces in 265.[29]

Li Mu then prepared a large army that consisted of 1,300 war chariots, 13,000 cavalry, 50,000 picked infantry and 100,000 expert archers. With the full army he carried out military exercises. Then he scattered this large force around the pastures and the countryside. The Xiongnu first sent a small contingent to raid the border, and Li Mu pretended to be defeated, and abandoned to the Xiongnu a few thousand men. The shanyü [title for the chief of the Xiongnu] heard of this and then sent a large force to invade [Zhao]. Li Mu with his large array of troops, divided into two armies, from right and left encircled and beat the Xiongnu, and inflicted a great defeat on them, killing hundreds of thousands of men and horses. Following this, he exterminated the Dan Lan, defeated the Dong Hu, forced the Lin Hu to surrender, and made the shan-yü flee far away. Ten years after this, the Xiongnu still did not dare come close to the cities on the border of Zhao.[30]

— Nicola Di Cosmo

Chu conquest of Lu (255 BC)

Qin conquest of Zhao (236–222 BC)

In 236, Qin allied with Yan against Zhao. Qin forces under Wang Jian and Huan Yi attacked Zhao forces under Li Mu and Hu Zhe from the rear. Meanwhile, Zhao general Pang Nuan faced off against the Yan army. In 234, Qin forces dealt a defeat to Zhao at Pingyang; however, Qin suffered a loss the year after when Li Mu forced Huan Yi to flee to Yan. The Qin attacked again in 232 but they were defeated again at Fanwu. In 229, a drought severely weakened Zhao, inciting Qin to take advantage of the situation and invade. Wang Jian also successfully infiltrated the Zhao court and bribed the high dignitary Guo Kai to accuse Li Mu of rebellion. King Youmiu had Li Mu executed and replaced with Zhao Cong and Yan Ju. Not soon thereafter, the Zhao capital of Handan fell to Wang Jian. Zhao remnants fled to Dai Commandery and Zhao Jia ruled there as the king of Dai until the Qin general Wang Ben eliminated them in 222.[32]

Qin conquest of Han (230–226 BC)

In 230, Han submitted to Qin. Rebellions by Han nobility lasted until 226 when the last Han monarch, King An of Han, was executed.[33]

Qin conquest of Yan (227–222 BC)

In 227, Crown Prince Dan of Yan had the head of Huan Yi, who fled battle against the Zhao general Li Mu, delivered back to Qin under the guise of appeasement. When presenting the head to the Qin King Ying Zheng, the emissary Jing Ke attempted to assassinate him but failed. In retaliation, Qin generals Wang Jian and Xin Sheng attacked and defeated Yan and Dai forces at River Yi. King Xi of Yan executed Crown Prince Dan to mollify Qin, but Yan was conquered anyway in 222, after Qin had finished the campaign against Chu.[34]

Qin conquest of Wei (225 BC)

In 225, Qin general Wang Ben diverted the Yellow River to flood Daliang. King Jia of Wei was captured and Qin annexed Wei.[35]

Qin conquest of Chu (225–222 BC)

In 225, Qin generals Li Xin and Meng Tian led a 200,000 strong army against Chu. General Wang Jian believed that only a 600,000 strong army would be able to overcome Chu, but Li Xin argued that it was doable with only 200,000. While Li Xin scored several initial victories, the Chu general Xiang Yan, for the most part just avoided battle and attacked the Qin commandery of Nanyang instead. Overcome with confidence, Li Xin was unprepared when Xiang Yan returned, and was defeated. The Qin returned to Chu in 224 with an army of 600,000 under Wang Jian. The two sides entered a stalemate in the region of Chen, but the Chu King Fuchu was eager to achieve victory, and commanded Xiang Yan to attack the Qin army. When the attack failed and Xiang Yan was forced to retreat, the Qin attacked in earnest and annihilated the Chu forces. Shouchun fell soon after.[36]

Qin conquest of Qi (221 BC)

King Jian of Qi did not prepare for the Qin invasion. Wang Ben had previously bribed the Qi counselor Hou Sheng to neglect the army and not to support the other states militarily. It was said that when the Qin finally invaded Qi in 221, King Jian surrendered without a fight. When the Qin army took Linzi, the people displayed no sign of resistance. Ying Zheng declared himself Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty.[37][38]

Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu (215 BC)

In 215 BC, Qin general Meng Tian led a 300,000 strong army against the Xiongnu in the Ordos region and evicted them from the area. Meng Tian then had walls erected, stretching from Lintao to Liaodong, a distance of some ten thousand li.[39]

An inscription erected at Mt. Jieshi in the same year says this of Qin Shi Huang:

He has been the first to achieve a single great peace.

He has demolished the inner and outer walls of cities.

He has cut through the embankments of rivers.

He has levelled the bulwarks at mountain defiles.[40]

Qin campaign against the Yue tribes (214 BC)

In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang ordered the construction of the Lingqu Canal, which in its completion stretched 2,000 kilometers north to south, linking the Xiang River and Li River. The new canal allowed the Qin to send armies and colonists south to conquer the Baiyue, annexing lands stretching from Fujian to Guangdong.[41]

Shang Yang's Reforms

The rapid growth of Qin's military began with the adoption of Shang Yang's Legalist reforms beginning in 361 BC. Shang Yang was originally a minor official in the state of Wei, but failed to gain recognition there and defected to Qin in 361 BC. Shang Yang personally led the Qin army to wage war on his native homeland and recovered territory previously lost to Wei. This forced Wei to shift its capital eastward to Daliang in 340 BC. Unfortunately, after the death of Duke Xiao of Qin in 338 BC, Shang Yang was accused of treason and killed.[42]

Shang Yang's reforms encompassed a broad ranging overhaul of Qin society which centralized political power and geared society towards greater agricultural efficiency and mass military conscription.[43]

Lord Shang’s overall aim was to mobilize the state for warfare. He saw the great mass of commoners as a resource of the state to further its military objectives; common people were to devote themselves to agriculture to support the army and were also subject to military conscription and corvée labor. They were to be kept ignorant, docile, and obedient, and were kept in line by a code of laws that provided ferocious punishments for all infractions (such as mutilation or being torn apart limb by limb). Household registration was also a form of control. Households were registered in groups of five; each was responsible for the others. If a crime occurred and was not reported by the miscreant’s neighbors in their household group, all five would be subject to punishment along with the actual criminal. Explicit regulations also governed the conduct of government officials, who could be punished both for failing to carry out their stated responsibilities and for encroaching on the duties of others. In general the civilian government was subordinated to the armed forces and the chief means of advancement in rank was prowess on the battlefield, measured by the number of enemy heads taken. In the end Shang Yang overreached himself and, by amassing too much power, incurred the jealousy of others. After the death of Lord Xiao, Shang Yang was accused of treason and executed by being tied to two chariots and torn apart. But his reforms endured, launching Qin on a century-long drive for power and continuing to form the basis of Chinese law during the imperial age.[44]

— John S. Major

Politics

In 350 BC, Shang Yang reorganized Qin into 31 counties, each administered by a centrally appointed magistrate.[45]

Agriculture

Shang Yang reduced the power of hereditary landholders by replacing labor services with taxation. The well field system under which peasants cultivated plots of land for their overlords was abolished. Peasants were given the right to sell and buy farmland to entice resettlement from neighboring populations.[46]

Law

Pillars were erected at the capital to promulgate new laws, which emphasized that "The punishments did not spare the strong and great" and meritorious service would be rewarded.[47]

Group responsibility

The population was divided into units of five or ten families, within which all members were responsible for each other's actions.

Whoever did not denounce a culprit would be cut in two; whoever denounced a culprit would receive the same reward as he who decapitated an enemy; whoever concealed a culprit would receive the same punishment as he who surrendered to an enemy[47]

Shang Yang also sought to weaken family solidarity by applying double taxes to households with more two or more adult males living together. In 350 BC, he outright forbade fathers and adult sons or brothers from cohabiting with one another.[48]

Ranks

Shang Yang created a system of eighteen ranks, each gained through slaying one enemy, which conferred benefits such as tax and labor exemptions or land and office. However, later in 243 BC, ranks could also be gained by contributing grain to the government.[48]

Standardization

Weights and measures were standardized to facilitate governance.[49]

Military ideology

From antiquity to the present time, it has never happened that one attained supremacy without conquest, or that one came to ruin without defeat. If the people are brave, one conquers in war, but if they are not brave, one is defeated in war. If one can unify the people for war, they are brave, but if one cannot unify the people for war, they are not brave. A sage-king obtains the kingship through the efforts of his soldiers. Therefore, he rouses the country and charges it with the obligation of military service. If one enters a state and sees its administration, it is strong if its people are of use. How does one know that the people are of use? If they, on perceiving war, behave like hungry wolves on seeing meat, then they are of use. Generally, war is a thing that people hate; he who succeeds in making people delight in war attains supremacy.[50]

All males were expected to perform military service as part of their tax obligation. At the age of 16, males were called up for military training in their locality for one year, then they spent another year of training at the capital. However, only one male per family was liable to be called up for military training at any one time in order to ensure they still had enough men to produce crops. After that they were discharged to return home and farm with a scheduled military review every three years.[51]

Formations

In general, there are ten formations: square (fang 方), round (yuan 圓), dispersed (shu 疏), dense (shu 數), awl (zhui hang 錐行), geese (yan hang 雁行), hook (gou hang 鉤行), dark wings (xuanyi 玄翼), fire (huo 火), and water (shui 水). These all have their particular advantages. The square formation is for cutting through the enemy. The round formation is for concentrating the enemy. The dispersed formation is for . . . [undeciphered text]. The dense formation is for preventing enemy penetrations. The awl formation is for penetrating enemy lines. The geese formation is for closing with the enemy with bow and arrow. The hook formation is for making rapid changes in battle plans. The dark wings formation is for placing the enemy in doubt and encumbering the enemy’s resoluteness. The fire formation is for seizing the enemy [by means of fire or extracting oneself from enemy attack by fire]. And the water formation is for disrupting the enemy [when attacking by water or defending against enemy attacks by water].[52]

Sun Bin advised deploying long weapons on the front lines, short weapons behind, and with support from archers.[53] Square formations were suited to level ground, round formations to rugged ground, pointed formation when facing higher ground, and a square formation with wings when enveloping a battle line.[54] Sun Bin also provides a general guideline for some formations to follow:[55]

- Square formations should be sparse in the center, thick at the sides, and especially strong in the back.

- Dispersed formations are for when there is little armour and manpower, so that a formation appears strong and firm. By setting up banners, flags, sharpened weapons at the edges, and arraying numerous small groups to advance and retreat, one can intimidate the enemy.

- Dense formations should have troops travelling in close quarters with enough room to wield weapons properly and not injure each other. It should be tightly woven and contain no gaps.

- Awl formations should be thick at the base and sharp at the edges.

- Hook formations should have a front line that is straight with wings that are curved.

- Dark wing formations must be well ordered and use many flags and insignia, so that when they all move at once, the foot soldiers cause an immense racket.

Chariots and cavalry

Warfare during the earlier period was dominated by chariot-riding aristocrats who fought one another according to rules of chivalry and for whom prestige and “face” meant more than practical gain. The later wars were dominated by professional generals who fought grimly to acquire territory and resources for whatever state employed them. The role of war chariots (always hard to maneuver in irregular terrain) diminished greatly, while that of massed infantry correspondingly increased. From the horseback-riding pastoral peoples of Inner Asia, the Chinese learned, at the end of the fourth century (specifically in the state of Zhao in 307), how to use mounted archers as an important supplement to infantry.[56]

— Derk Bodde

Cavalry was first adopted by the state of Zhao at the end of the 4th century BC. King Wuling of Zhao ordered his soldiers to wear rider jackets and trousers like the barbarians.[57] Horsemen acted as scouts or raiders and were deployed in battle along with chariots. Sun Bin recommended arraying the chariots and cavalry in three units, one on either flank, and one in the back. Even so, cavalry only played a tertiary role in Warring States warfare, and chariots remained the preferred mobile force on flat terrain.[58] The Qin chose the strongest and tallest men for their cavalry and chariot forces while short men wen given spears and halberds.[51]

-

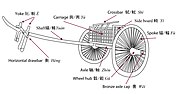

Warring States chariot diagram

-

Qin dynasty chariot from the Terracotta Army

-

Qin charioteer

-

Standing charioteer

-

Qin chariot

-

Kneeling charioteer

Armour

In the 4th century BC, rhinoceros armour was still used. In the following passage Guan Zhong advises Duke Huan of Qi to convert punishments to armour and weapons:

Ordain that serious crimes are to be redeemed with a suit of rhinoceros armour and one halberd, and minor crimes with a plaited leather shield and one halberd. Misdemeanours are to be punished with [a fine of] a quota of metal [jin fen 金分], and doubtful cases are to be pardoned. A case should be delayed for investigation for three [days] without allowing arguments or judgements; [by the time] the case is judged [the subject will have produced] one bundle of arrows. Good metal [mei jin 美金] should be cast into swords and halberd[-heads] and tested on dogs and horses, while poorer metal [e jin 惡金] should be cast into agricultural implements and tested on earth.[59]

— Guan Zhong

Lamellar armour

Lamellar armour of leather, bronze, and iron appeared by the mid-4th century BC. Lamellar consisted of individual armour pieces that were either riveted or laced together to form a suit of armour.[60] Iron helmets constructed with multiple pieces of iron lamellae began to replace the one piece bronze helmets of old. One sample discovered in Yi county, Hebei Province, was composed of 89 lamellae. The average dimensions of the lamellae pieces were 5 cm x 4 cm.[61]

In the 3rd century BC, both iron weapons and armour became more common. According to the Xunzi, "the hard iron spears of Wan (宛) [a city in Chu, near modern Nanyang (南陽), Henan] are as cruel as wasps and scorpions."[62] Iron weapons also gave Chinese armies an edge over barbarians. Han Fei recounts that during a battle with the Gonggong (共工) tribe, "the iron-tipped lances reached the enemy, and those without strong helmets and armour were injured."[63] As a result of the increasing effectiveness of iron weapons and armour, shields and axes became less common.[63] The efficiency of crossbows, however, outpaced any progress in defensive armour. It was considered a common occurrence in ancient China for commoners or peasants to kill a lord with a well aimed crossbow bolt, regardless of whatever armour he might have been wearing at the time.[64]

Shun taught the ways of good government for the following three years, and then took up shield and battle-ax and performed the war dance, and the Miao submitted. But in the war with the Gonggong, men used iron lances with steel heads that reached to the enemy, so that unless one was protected by a stout helmet and armor he was likely to be wounded. Hence shields and battle-axes served for ancient times, but no longer serve today. So I say that as circumstances change the ways of dealing with them alter too.[65]

— Han Fei

Armour was mostly restricted to elite guard units and each state distributed armour in their own ways. The state of Chu favorited elite armoured crossbow units known for their endurance, and were capable of marching 160 km 'without resting.'[60] Wei's elite forces were capable of marching over 40 km in one day while wearing heavy armour, a helmet, two swords, a halberd, a large crossbow with 50 bolts, and three days worth of rations. Those who met these standards earned an exemption from corvée labor and taxes for their entire family.[66]

According to Su Qin, the state of Han made the best weapons, capable of cleaving through the strongest armour, shields, leather boots, and helmets.[67] Their soldiers wore iron facemasks.[60]

By the end of the 3rd century BC, at least a few horsemen wore armour of some kind.[60]

-

Bronze helmet, Zhou dynasty

-

Warring States bronze helmet

-

Warring States shield (94.2 cm tall, 60 cm wide, 0.3 cm thick)

-

Bronze lamellar armour, Warring States period

-

Lamellar armour and helmet, Qin dynasty

-

Qin stone armour

Qin armour

The Qin calculated fines in terms of one or two coats of armour, lower crimes in terms of shields, and the lowest in terms of coins.[68] Qin soldiers sometimes threw off their armour and engaged in fast charges.[69] Qin armour usually used rectangular lamellae pieces with dimensions of 7.5 cm x 8.5 cm and 10.5 cm x 7.8 cm. Dimensions of lamellae used for charioteer armour varies between the upper body, lower body, and arms. Lamellae on the upper body were 7 cm x 6 cm, the lower body 9 cm x 6.5 cm, and arms 4-7.5 cm x 4 cm. Lamellae pieces on cavalrymen were 8 cm x 5.7 cm.[70] A complete set of Qin armour, judging by the finds in the Terracotta Army consisted of 250 to 612 lamellae pieces in total, not including the helmet.[71]

Six groups of armour have been identified in the Terracotta Army corresponding to rank and military division. Ordinary soldiers are outfitted with no armour at all, cavalrymen with armour that covered the chest, armed infantrymen with armour covering the torso and shoulders, low-ranking officers with armour using large lamellae piece, middle-ranking officers with shorter armour covering the torso and waist or just the breast, but with decorations such as ribbons, and high-ranking officers with a distinctive coat showing torso armour and ribbons to signify their status. No soldiers have been found wearing a helmet or holding a shield. The high-ranking officer wears a pheasant-tail headdress while a middle ranking officer wears a long flat cap. Both armed infantrymen and cavalrymen have soft caps, but while the infantry cap accommodates the top knot, the cap for cavalrymen is flat and tied below the chin.[72]

There is some evidence that armour for horses might have existed for Qin cavalry judging by 300 lamellae pieces too large for human use.[73]

Swords and polearms

Iron and steel swords of 80 to 100 cm in length appeared during the mid Warring States period in the states of Chu, Han, and Yan. The majority of weapons were still made of bronze but iron and steel weapons were starting to become more common.[74] By the end of the 3rd century BC, the Chinese had learned how to produce quench-hardened steel swords, relegating bronze swords to ceremonial pieces.[75] According to the Xunzi, the city of Wan in the state of Chu made the best steel weapons. After Chu was conquered by Qin, ironworkers were foricbly relocated there to work the local iron industry.[76]

By the end of the 4th century BC, dagger-axes with spearheads began to appear, essentially becoming a halberd. Spears and halberds came in two general sizes. One about 2.8 m long and the other around 5.5 m, or what would be considered a pike in western terminology.[77] According to Wu Qi, tall men were given bows and arrows while short men spears and halberds.[78]

The Zhan Guo Ce states that the state of Han made the best weapons, capable of cleaving through the strongest armour, shields, leather boots, and helmets.[67]

Sword dances are mentioned shortly after the end of the Qin dynasty.[79] Swords up to 110 cm in length began to appear.[80]

-

Warring States halberd (ji)

-

Warring States lance (pi)

-

Mace spear from the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng

-

Bronze cudgel, Eastern Zhou

-

Qin jians

Crossbow

In terms of archaeological evidence, crossbow locks made of cast bronze have been found in China dating to around 650 BC.[81] They have also been found in Tombs 3 and 12 at Qufu, Shandong, previously the capital of Lu, and date to 6th century BC.[82][83] Bronze crossbow bolts dating from the mid-5th century BC have been found at a Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province.[84] Other early finds of crossbows were discovered in Tomb 138 at Saobatang, Hunan Province, and date to mid-4th century BC.[85][86] It's possible that these early crossbows used spherical pellets for ammunition. A Western-Han mathematician and music theorist, Jing Fang (78-37 BC), compared the moon to the shape of a round crossbow bullet.[87] Zhuangzi also mentions crossbow bullets.[88]

The earliest Chinese documents mentioning a crossbow were texts from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC attributed to the followers of Mozi. This source refers to the use of a giant crossbow between the 6th and 5th centuries BC, corresponding to the late Spring and Autumn Period. Sun Tzu's The Art of War (first appearance dated between 500 BC to 300 BC)[89] refers to the characteristics and use of crossbows in chapters 5 and 12 respectively,[90] and compares a drawn crossbow to 'might.'[91]

The state of Chu favorited elite armoured crossbow units known for their endurance, and were capable of marching 160 km 'without resting.'[60] Wei's elite forces were capable of marching over 40 km in one day while wearing heavy armour, a large crossbow with 50 bolts, a helmet, a side sword, and three days worth of rations. Those who met these standards earned an exemption from corvée labor and taxes for their entire family.[66]

Repeating crossbow

The Zhuge Nu is a handy little weapon that even the Confucian scholar or palace women can use in self-defence... It fires weakly so you have to tip the darts with poison. Once the darts are tipped with "tiger-killing poison", you can shoot it at a horse or a man and as long as you draw blood, your adversary will die immediately. The draw-back to the weapon is its very limited range.[81]

According to the Wu-Yue Chunqiu (history of the Wu-Yue War), written in the Eastern Han dynasty, the repeating crossbow was invented during the Warring States Period by a Mr. Qin from the State of Chu. This is corroborated by the earliest archaeological evidence of repeating crossbows, which was excavated from a Chu burial site at Tomb 47 at Qinjiazui, Hubei Province, and has been dated to the 4th century BC, during the Warring States Period (475 - 220 BC).[92] Unlike repeating crossbows of later eras, the ancient double shot repeating crossbow uses a pistol grip and a rear pulling mechanism for arming. The Ming repeating crossbow uses an arming mechanism which requires its user to push a rear lever upwards and downwards back and forth.[93] Although hand held repeating crossbows were generally weak and required additional poison, probably Aconitine, for lethality, much larger mounted versions appeared during the Ming dynasty.[81]

The invention of the repeating crossbow has often been attributed to Zhuge Liang but he in fact had nothing to do with it. This misconception is based on a record attributing improvements to the multiple bolt crossbows to him.[94]

Mounted crossbow

Large mounted crossbows known as "bed crossbows" were used as early as the Warring States period. Mozi described them as defensive weapons placed on top the battlements. The Mohist siege crossbow was described as a humongous device with frameworks taller than a man and shooting arrows with cords attached so that they could be pulled back. By the Han dynasty, crossbows were used as mobile field artillery and known as "Military Strong Carts".[95] Around the 5th century AD, multiple bows were combined together to increase draw weight and length, thus creating the double and triple bow crossbows. Tang versions of this weapon are stated to have obtained a range of 1,160 yards, which is supported by Ata-Malik Juvayni on the use of similar weapons by the Mongols in 1256.[96]

Multiple bolt crossbow

The multiple bolt crossbow appeared around the late 4th century BC. A passage dated to 320 BC states that it was mounted on a three-wheeled carriage and stationed on the ramparts. The crossbow was drawn using a treadle and shot 10 foot long arrows. Other drawing mechanisms such as winches and oxen were also used.[97] Later on pedal release triggers were also used.[98] Although this weapon was able to discharge multiple bolts, it was at the cost of reduced accuracy since the further the arrow was from the center of the bow string, the more off center its trajectory would be.[95] It had a maximum range of 500 yards.[99]

When Qin Shi Huang's magicians failed to get in touch with "spirits and immortals of the marvellous islands of the Eastern Sea", they excused themselves by saying large monsters blocked their way. Qin Shi Huang personally went out with a multiple bolt crossbow to see these monsters for himself. He found no monsters but killed a big fish.[100]

Siege equipment

Warring States siege equipment consisted of siege ladders, siege towers, and the traction trebuchet.[101] The traction trebuchet, also referred to as a mangonel in some sources, is an artillery weapon which derives from manpower its motive force, and was probably used by the Mohists starting from the 4th century BC. Descriptions of it can be found in the Mojing (compiled in the 4th century BC). It consisted of an arm and sling mounted on a wooden frame, sometimes with wheels. Attached to one end of the arm were pulling ropes for men to power the weapon.[102] Trebuchets mounted on wheels were said to have needed 200 men to pull each of them.[103] In Chapter 14 of the Mojing, the traction trebuchet is described hurling hollowed out logs filled with burning charcoal at enemy troops.[95] Mobile siege towers have been used in China since the 6th century BC. They were often called overlook carts, assault carts, or some combination of the two.[95] A typical mobile siege tower was five stories tall mounted on axles with two wheels on each side. The tower was pushed forward by men on the lowest storey or pulled by horses and oxen.[104]

The king of Wu mentioned it in a passage comparing land armies to the navy.

These days in training we use the (same) tactics of land armies for the best effect. Thus big wing ships correspond to the army's heavy chariots, small wing ships to their light chariots, stomach strikers to battering rams, castled ships to mobile assault towers and bridge ships to the light cavalry.[95]

— King of Wu (514 - 496 BC)

Army sizes

The army sizes given by the Records of the Grand Historian for the Warring States are almost certainly highly inflated. At several points it gives army figures upwards of several hundred thousand for both Qin and its enemies, each of which would be larger than the entire army mobilized by the Han dynasty at its height, which ranged from around 130,000 to 300,000 under Emperor Wu of Han.[105]

Sun Tzu, for example, calculates the cost of provisions, equipment and other expenses for an expedition of 100,000 men at a fairly precise 1,000 pieces of money per day. On the other hand it seems to have been customary to state any large number in units of ten or a hundred thousand, and the chroniclers were probably in the habit of using these figures to denote units of approximately that nominal strength. One entry in the Official History of the Han dynasty implies as much when it states that the men collected for one campaign against the Hsiung-nu numbered more than 40,000, ‘and were called a hundred thousand’. This may have been done simply for administrative convenience or to denote the appropriate level of command, in the same way as we might refer to a brigade or a division, regardless of whether or not it is actually at full strength. The corrupt practice of commanders inflating the numbers on the rolls in order to siphon off surplus pay and rations, which is known to have been a major problem under later dynasties, may also have been a factor. It may be best to consider the figures given in narrative sources as useful for relative strengths but not for absolute ones, or if we insist of hazarding a guess at the latter, the ratio of forty to a hundred indicated in the passage quoted above may be at least a rough guide.[106]

— Chris Peers

Gallery

-

Qin soldiers

-

Qin standing archer

-

Qin kneeling archer

-

Qin officer

-

Qin general

-

Qin arrows

See also

Citations

- ^ (秦国兵阵分散,各自为战) (Rough Translation: The nature of Qin's troops is to disperse so that each unit fights their own respective battles)

- ^ 秦国人性情强悍,它的地势险要,政令严明,赏罚分明,分明,士卒临阵勇猛而斗志高昂,所以能在分散的阵势中各自奋战。打击秦兵的方法是,先施以小利引诱它的士兵脱离主将的指挥,此时,我军就可以逐一击破其分散队伍,并设置伏伺机取胜,就可以擒获它的将领。) (Rough Translation: The people of Qin are ferocious by nature and their terrain is treacherous. The government's decrees are strict and impartial. The rewards and punishments are clear. Qin soldiers are brave and high in morale so that they are able to scatter and engage in individual combat. To strike at Qin's army, we must entice various groups with small benefits; the greedy will abandon their general to give chase. We can then capitalize on this opportunity by hunting each group down individually and then capturing the generals that have been isolated. Finally, we must array our army to ambush their commander.)

- ^ (齐国兵力充足, 但其阵不坚固) (Rough Translation: Although Qi's troops are numerous, their organization is unstable)

- ^ (齐国人性情刚烈,国家富足,但君臣骄奢,忽视民众利益,政治松弛,俸禄分配不均,一阵之中人心不齐,兵力部署前重后轻,所以阵势浩大,但不坚实。打击齐兵的方法是,宜将我军分为三路,两路夹击它的左右翼,另一路承势追击,他的阵势便可破了。) (Rough Translation: The people of Qi are by nature unyielding and their country prosperous, but the ruler and officials are arrogant and care nothing for the people. The state's policies are not uniform and not strictly enforced. Salaries and wages are unfair and unevenly distributed, causing disharmony and disunity. Qi's army is arrayed with their heaviest hitters at the front while the rest follow behind, so that even when their forces appear mighty, they are in reality fragile. To defeat them, we should divide our army into three columns and have two attack the left and right flanks of Qi's army. Once their battle formations are thrown into disarray, the central column should be in position to attack and victory will follow.)

- ^ (楚国兵阵完整,但不能持久) (Rough Translation: Chu's military formations are complete but cannot be maintained for long)

- ^ (楚人性情柔弱,它的领土广大,政令混乱,民力疲惫,所以阵势虽然严整但不能持久。打击楚兵的方法是,要袭扰其驻地,先动摇其士气,然后突然进击再突然撤退,使其疲于应付,而不要急于和它决战。这样就能打败它的军队。) (Rough Translation: The Chu people are soft and weak. Their lands stretch far and wide, and the government cannot effectively administer the expanse. Their troops are weary and although their formations are well-ordered, they do not have the resources to maintain their positions for long. To defeat them, we must strike swiftly, unexpectedly and retreat quickly before they can counter attack. This will create unease in their weary soldiers and reduce their fighting spirit. Thus, with persistence, their army can be defeated.)

- ^ (燕国防守阵型坚固,但机动性不足) (Rough Translation: Yan's defensive formations are solid but lack flexibility)

- ^ (燕国人性情诚朴,行动谨慎,好勇尚义,但缺乏诈谋,所以它的阵势长于防守而不善于灵活出击。打击燕兵的方法是,一交战就压迫它,打了一下又迅速撤退,同时还要袭击它的后方,这样会使其将帅疑惑而士卒恐惧,此时,我军车骑埋伏在敌人撤退的必经之路上,就可以虏获燕军将领。) (Rough Translation: The Yan are a sincere and straightforward people. They act prudently, love courage and esteem righteousness while rarely employing deception. Thus they excel in defensive positions, but are immobile and inflexible. To defeat them, immediately apply pressure with small attacks and retreat rapidly. When they turn to face our attacks, we should keep a distance. Attack the rear as well where and when they least expect it. When they withdraw to face another threat, chase them. This will confuse their generals and create anxiety in their ranks. If we avoid conflict against their strong points and use our armored chariots to set ambushes, we can capture their generals and insure victory.)

- ^ (韩、赵两国兵力训练有素,但在战场上很难发挥实际效用。) (Rough Translation: The two states of Han and Zhao train their troops rigorously but have difficulty in applying their skills to the battlefield)

- ^ (韩与赵是中原国家。其民性情温顺,它的政治平和,百姓不好战斗,而且轻视将帅,不满意自己的待遇,士卒没有拼死效命的决心与斗志,所以阵势虽然整齐但不中用。打击它们的方法是,可用强大的兵力压制,如果敌人兵众来犯就与它对峙,如果它退却就追击,这样一来它的军队便会疲惫不堪。) (Rough Translation: Han and Zhao are states of the Central Plain. Theirs are a gentle people, weary from war and experienced in arms, but have little regard for their generals. The soldiers' salaries are meager and their officers have no strong commitment to their countries. Although their troops are experienced, they cannot be expected to fight to the death. To defeat them, we must concentrate large numbers of troops in our attacks to present them with certain peril. When they counterattack, we must be prepared to defend our positions vigorously and make them pay dearly. When they retreat, we must pursue and give them no rest. This will grind them down.)

- ^ Man, John (2009-03-05). The Terra Cotta Army: China's First Emperor and the Birth of a Nation. ISBN 9780786732067.

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty Rulers (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Shang 2014, p. 143.

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Loewe 1999, p. 640.

- ^ "Bai Qi 白起 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Dynasty - Warring States Period (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "The Regional State of Song 宋 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Li Mu 李牧 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Cosmo 2002, p. 153.

- ^ "The Regional State of Lu 魯 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ "The Regional State of Qi 齊 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Cosmo 2002, p. 175.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 34-35.

- ^ Major 2017, p. 150.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 35-36.

- ^ a b Twitchett 2008, p. 36.

- ^ a b Twitchett 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Rand 2017, p. 23.

- ^ a b Portal 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Rand 2017, p. 65-66.

- ^ Sun 2000, p. 336.

- ^ Sun 2000, p. 370.

- ^ Sun 2000, p. 378-379.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 24-25.

- ^ "Zhou Period Military (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ Porta 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Wagner 2008, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e Peers 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Dien 1981, p. 7.

- ^ Wagner 2008, p. 116.

- ^ a b Wagner 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Robinson 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Han 2003, p. 101.

- ^ a b Lewis 2007, p. 38.

- ^ a b Peers 2013, p. 60.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 50.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Dien 1981, p. 8.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 170, 181.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 145, 170.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 183.

- ^ Lorge 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Wagner 1996, p. 197.

- ^ Wagner 2008, p. 128.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Lorge 2011, p. 62.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Loades 2018.

- ^ You (1994), 80.

- ^ A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China Archived 2008-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Asian Traditional Archery Research Network. Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ^ Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China: Second Impression, With Corrections. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09632-9. pp. 153, 157–158.

- ^ Mao (1998), 109–110.

- ^ Wright (2001), 159.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd, p. 227.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 89.

- ^ James Clavell, The Art of War, prelude

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Needham 1994, p. 34.

- ^ Lin, Yun. "History of the Crossbow," in Chinese Classics & Culture, 1993, No.4: p. 33–37.

- ^ Unique weapon of the Ming Dynasty — Zhu Ge Nu (諸葛弩), 24 September 2015, retrieved 16 April 2018

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Liang 2006.

- ^ Turnbull 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 189-190.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 192.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 188.

- ^ Turnbull 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Turnbull 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Turnbull 2001, p. 18-19.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 439.

- ^ Twitchett 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Peers 2013, p. 55.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (2002), Ancient China and Its Enemies, Cambridge University Press

- Coyet, Frederic (1975), Neglected Formosa: a translation from the Dutch of Frederic Coyett's Verwaerloosde Formosa

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Han, Fei (2003), Han Feizi: Basic Writings, Columbia University Press

- Jackson, Peter (2005), The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education Limited

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011), China's Southern Tang Dynasty, 937-976, Routledge

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Loades, Mike (2018), The Crossbow, Osprey

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Loewe, Michael (1999), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge University Press

- Major, John S. (2017), Ancient China: A History, Routledge

- Mesny, William (1896), Mesny's Chinese Miscellany

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Portal, Jane (2007), The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army, Harvard University Press

- Rand, Christopher C. (2017), Military Thought in Early China, SUNY Press

- Robinson, K.G. (2004), Science and Civilization in China Volume 7 Part 2: General Conclusions and Reflections, Cambridge University Press

- Shang, Yang (2014), The Book of Lord Shang, Lionshare Media

- Sun, Tzu (2000), The Art of War: Complete Texts and Commentaries, Shambhala

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612-1300, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 960-1644, Osprey Publishing

- Twitchett, Denis (2008), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, Cambridge University Press

- Wood, W. W. (1830), Sketches of China

- Wagner, Donald B. (1996), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, E.J. Brill

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press

- Wright, David (2005), From War to Diplomatic Parity in Eleventh Century China, Brill

- Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Angus McBridge, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 0-85045-942-7

- Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Michael Perry, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-514-4

- Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Michael Perry, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-599-3

- Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by David Sque, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-254-4

- Late Imperial Chinese Armies: 1520-1840 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Christa Hook, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-655-8