David Markson

David Markson | |

|---|---|

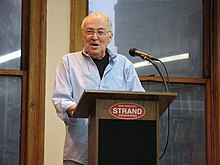

Markson in September 2007 | |

| Born | December 20, 1927 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | (body found) June 4, 2010 (aged 82) Greenwich Village, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Education | Columbia University (MA) |

| Period | postmodern |

| Genre | experimental fiction |

| Years active | 1956 – 2007 |

| Notable works | Going Down, Springer's Progress, Wittgenstein's Mistress, Reader's Block, This Is Not A Novel, Vanishing Point, The Last Novel |

David Merrill Markson (December 20, 1927 – c. June 4, 2010)[1] was an American novelist. He was the author of several postmodern novels, including Springer's Progress, Wittgenstein's Mistress, and Reader's Block. His final book, The Last Novel, published in 2007, was called "a real tour de force" by The New York Times.[2]

Markson's work is characterized by an unconventional and experimental approach to narrative, character development and plot. The late writer David Foster Wallace hailed Wittgenstein's Mistress as "pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country".[3] While his early works draw on the modernist tradition of William Faulkner and Malcolm Lowry, his later novels are, in Markson's words, "literally crammed with literary and artistic anecdotes" and "nonlinear, discontinuous, collage-like, an assemblage."[4]

In addition to his output of modernist and postmodernist experimental literature, he published a book of poetry,[5] a critical study of Malcolm Lowry,[6] three crime novels, and an anti-Western, The Ballad of Dingus Magee, adapted into the film Dirty Dingus Magee, starring Frank Sinatra.[7]

Biography

[edit]He was of Jewish origin.[8] David Merrill Markson was born in Albany, New York, on December 20, 1927.[5][9]

Educated at Union College and Columbia University, Markson began his writing career as a journalist and book editor, periodically taking up work as a college instructor at Columbia University, Long Island University, and The New School.[10]

Though his first novel was published in the late 1950s, he did not gain prominence until the late 1980s, when he was over 60 years old, with the publication of Wittgenstein's Mistress. From that point, his reputation as a writer steadily grew, so much so that he told an interviewer: "One of my friends told me to be careful before I become well known for being unknown."[4]

Markson died in New York City, in his West Village apartment where, according to the author's literary agent and former wife Elaine Markson, Markson's two children found him on June 4, 2010 in his bed.[1][11]

Upon David Markson's death, his entire personal library was donated to the Strand Bookstore, according to his wishes.

Wittgenstein's Mistress

[edit]Wittgenstein's Mistress, widely considered his masterpiece, was published in 1988 by Dalkey Archive Press. Though Markson's original manuscript was rejected 54 times,[12] the book, when finally published, met with critical acclaim. It is a highly stylized, experimental novel in the tradition of Beckett. The novel is mainly a series of statements made in the first person; the protagonist is a woman who believes herself to be the last human on earth. Though her statements shift quickly from topic to topic, the topics are often recurrent, and often reference Western cultural icons, ranging from Zeno to Beethoven to Willem de Kooning. Readers familiar with Ludwig Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus will recognize striking stylistic similarities to that work.

Amy Hempel praised it for "address[ing] formidable philosophic questions with tremendous wit."[13] A decade later, David Foster Wallace described it as "pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country" in an article for Salon entitled "Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels >1960."[14]

Markson's Tetralogy (aka The Notecard Quartet)

[edit]Markson's late works further refine the allusive, minimalist style of Wittgenstein's Mistress. He hoped that these four novels might eventually be published together in one volume.[15] Thus, critics often discuss them as a tetralogy and, though Markson himself gave no title to this collection of novels, many critics have adopted the name The Notecard Quartet to describe this work as a whole.[16][17][18][19]

Markson described the action of this tetralogy as a character "sitting alone in a bedroom with a head full of everything he’s ever read." Most of the traditional comforts of the novel form are absent, as an author-figure closely identified with Markson himself[20] considers the travails of the artist throughout the history of culture. In Reader's Block, he is called Reader; in This Is Not A Novel, Writer; in Vanishing Point, Author; in Markson's last novel, The Last Novel, he is known as Novelist. His working process involved "scribbling the notes on three-by-five-inch index cards" and collecting them in "shoebox tops" until they were ready to be put "into manuscript form."[21]

The first in the “personal genre,” Reader's Block, was published by Dalkey Archive Press in 1996. It was followed by This Is Not A Novel (Counterpoint, 2001), Vanishing Point (Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004) and The Last Novel (Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007). Of Reader's Block, fellow writer and friend Kurt Vonnegut wrote, "David shouldn’t thank Fate for letting him write such a good book in a time when large numbers of people could no longer be wowed by a novel, no matter how excellent."

The second book, This Is Not a Novel,[22] describes itself in a number of terms:

- "A novel" (p. 18)

- "An epic poem" (p. 21)

- "A sequence of cantos awaiting numbering"(p. 23)

- "A mural of sorts" (p. 36)

- "An autobiography" (p. 53)

- "A continued heap of riddles" (p. 70)

- "A polyphonic opera of a kind" (p. 73)

- "A disquisition on the maladies of the life of art" (p. 86)

- "An ersatz prose alternative to The Waste Land" (p. 101)

- "A treatise on the nature of man" (p. 111)

- "An assemblage [nonlinear, discontinuous, collage-like]" (p. 128)

- "A contemporary variant on [The Egyptian Book of the Dead]" (p. 147)

- "A kind of verbal fugue" (p. 170)

- "A classic tragedy [in many ways]" (p. 171)

- "A volume entitled 'Writer's Block'" (p. 173)

- "A comedy of a sort" (p. 184)

- "His synthetic personal Finnegans Wake" (p. 185)

- "Nothing more than a fundamentally recognizable genre all the while" (p. 189)

- "Nothing more or less than a read"

- "An unconventional, generally melancholy though sometimes even playful now-ending read."

In This Is Not a Novel, the Writer character states, "A novel with no intimation of story whatsoever, Writer would like to contrive" (p. 2). Reader's Block, likewise, calls itself "a novel of intellectual reference and allusion, so to speak minus much of the novel" (p. 61). Rather than consisting of a specific plot, they can be said to be composed of "an intellectual ragpicker's collection of cultural detritus."[23] This seemingly-random set of quotes, ideas, and nuggets of information about the lives of various literary, artistic, and historical figures cohere to form a new kind of novel. Despite their unconventional form and appearance, Markson insisted on calling them "novels."[24]

Though the last three novels of The Notecard Quartet have been published together in one book, This Is Not a Novel and Other Novels, because the first book of the tetralogy was published by a different publisher, the entire quartet of novels has yet to be published together in one collection.

Works

[edit]- Epitaph for a Tramp Dell, 1959.

- Epitaph for a Dead Beat Dell, 1961.

- The Ballad of Dingus Magee; Being the Immortal True Saga of the Most Notorious and Desperate Bad Man of the Olden Days, His Blood-Shedding, His Ruination of Poor Helpless Females, & Cetera; also including the Only Reliable Account ever offered to the Public of his Heroic Gun Battle with Sheriff C. L. Birdsill, Yerkey's Hole, New Mex., 1884, and with Additional Commentary on the Fateful and Mysterious Bordello-Burning of the Same Year; and furthermore interspersed with Trustworthy and Shamelessly Interesting Sketches of "Big Blouse" Belle Nops, Anna Hot Water, "Horseface" Agnes, and Others, hardly any Remaining Upright at the End. Composed in the Finest Modern English as taken diligently from the Genuine Archives Bobbs-Merrill, 1965. (Filmed as Dirty Dingus Magee (1970),

- Miss Doll, Go Home Dell, 1965.

- Going Down Holt Rinehart Winston, 1970.

- Springer's Progress Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1977.

- Malcolm Lowry's Volcano: Myth, Symbol, Meaning Times Books, 1978.

- Wittgenstein's Mistress Dalkey Archive, 1988.

- Collected Poems Dalkey Archive Press, 1993.

- The Notecard Quartet, 1996-2007

- Reader's Block Dalkey Archive Press, 1996.[25]

- This Is Not a Novel Counterpoint, 2001.

- Vanishing Point Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004.

- The Last Novel Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Legacy.com Featured Tribute: David Markson as of June 7, 2010, when this article was published, the exact time of Markson's death is not known. This article states that his body was found on June 4, 2010

- ^ Texier, Catherine (July 8, 2007). "Old. Tired. Sick. Alone. Broke". New York Times.

- ^ David Foster Wallace. "[1]", Salon, April 12, 1999. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Bookslut interview with David Markson". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- ^ a b Niagara Falls Reporter

- ^ "David Markson Bibliography". Archived from the original on 2012-07-15.

- ^ "IMDB page for Dirty Dingus Magee". IMDb.

- ^ EDT, Seth Colter Walls On 7/29/10 at 7:45 AM (2010-07-29). "All the Sad Old Literary Artifacts of David Markson". Newsweek. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "David Markson: An Introduction".

- ^ "David Merrill Markson" in Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson Gale, 2007.

- ^ Long Island Press: David Markson, postmodern master, dead at age 82 Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Reading Markson Reading, The last page of David Markson’s copy of The Failure of Criticism Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine by Henri Peyre

- ^ Amy Hempel. "Home is Where the Art Is", The New York Times, May 22, 1988. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ Salon, April 12, 1999, "Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels >1960"

- ^ KCRW Bookworm Interview with David Markson Archived 2013-10-26 at the Wayback Machine:

"I'm hoping one day--I don't imagine I'll still be here--but these four books, perhaps one more, will be printed in one volume."

- ^ Fletcher, Richard; Hanink, Johanna (2016-11-21). Creative Lives in Classical Antiquity: Poets, Artists and Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-15908-2.

- ^ Drag, Wojciech (2019-11-12). Collage in Twenty-First-Century Literature in English: Art of Crisis. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-76067-5.

- ^ "TFW You Realize Maybe David Markson Invented Twitter". Literary Hub. 2015-09-16. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Biblioklept (2015-08-18). "Issue 1.1 of The Scofield catches up to David Markson". Biblioklept. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Palleau-Papin, Francoise. This Is Not A Tragedy. Dalkey Archive Press, 2011. Pg. xxvii of the Introduction: Markson is quoted as having said: "How much of myself is in there? It’s all me. Especially in Reader’s Block, all that personal stuff re: Reader and/or Protagonist, ex-wife, ex-galfriends, children, lack of money, isolation, messed-up life, and/or some items dictated by novelistic necessity—and of course there is necessary invention there also, e.g., a house at a cemetery—but even little items like a couple of yellow stones from Masada or a reproduction of Giotto’s Dante—I plucked up whatever was ready at hand. Is that laziness, or is it what they speak of as using what one knows? Take your pick." ISBN 1-56478-607-2

- ^ Markson, David. Vanishing Point. Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004. Pg. 1. ISBN 1-59376-010-8

- ^ Markson, David. This Is Not a Novel. Counterpoint, 2001. ISBN 1-58243-133-7

- ^ Reading Markson Reading, Pg. 104 of David Markson’s copy of On the Iliad Archived 2011-08-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Richard Kalich, The Assisted Living Facility Library (Green Integer, 2020), 116.

- ^ Markson noted that unauthorized changes were made for the 2nd printing (2001) and asked readers to avoid it; see Laura Sims, Fare Forward: Letters from David Markson (powerHouse Books, 2014), p. 144. The 3rd printing of 2007 deleted most of the changes.

- ^ "David Markson: A Bibliography". Madinkbeard. 2007-04-20. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

Further reading

[edit]- John Barth / David Markson Number. Review of Contemporary Fiction. 10.2 (Summer 1990): 91-254.

- Palleau-Papin, Francoise. Ceci n'est pas une tragédie. L'écriture de David Markson. ENS Editions, 2007. ISBN 978-2-84788-106-6. English version (translated by the author): This Is Not a Tragedy: The Works of David Markson. Dalkey Archive Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-56478-607-4

- Sims, Laura. Fare Forward: Letters from David Markson. powerHouse Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-57687-700-5

- "David Markson and Solitude." The Scofield, 1.1 (August 2015). [2]

External links

[edit]- Biography and critical overview from American Writers Supplement XVII

- Introduction and Bibliography on David Markson

- Markson's Pier, a novella published in Essays & Fictions in the style of David Markson, by David Ewald and Stuart Ross

- Bookslut.com Interview with David Markson Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Context interview with David Markson[permanent dead link]

- Review of This is Not a Novel

- David Markson, Postmodern Experimental Novelist, Is Dead at 82 obituary from The New York Times published June 7, 2010

- "Address Unknown: David Markson, 1927-2010" in memoriam from n+1

- Dempsey, Peter (June 14, 2010). "David Markson obituary: Experimental US novelist who avoided literary safety nets". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 July 2010. This article was published on guardian.co.uk at 18.36 BST on Monday 14 June 2010. A version appeared on p35 of the Main section of the Guardian on Tuesday 15 June 2010.

- Corman, Catherine. "Remembering David Markson". The Economist Newspaper Limited. Retrieved 1 July 2010. This article appeared in the online version of Intelligent Life (Summer 2010).

- Sims, Laura. "Instead of Reading This, You Should Be Reading David Markson (Part One) : Laura Sims : Harriet the Blog". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- 1927 births

- 2010 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- Columbia University faculty

- Union College (New York) alumni

- Columbia University alumni

- Writers from Albany, New York

- American postmodern writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- Novelists from New York (state)

- People from Greenwich Village

- Writers from Manhattan