Vicksburg campaign

| Vicksburg campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Lithograph of the Mississippi River Squadron running the Confederate blockade at Vicksburg on April 16, 1863 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Tennessee | Army of Mississippi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~28,800–73,095[1] | ~43,600–65,800 (aggregate of Pemberton and Johnston)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,142 total | 38,586 total | ||||||

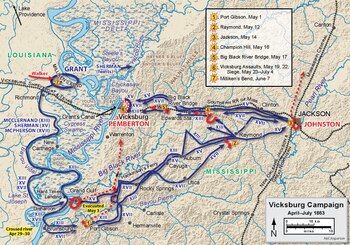

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate-controlled section of the Mississippi River. The Union Army of the Tennessee under Major General Ulysses S. Grant gained control of the river by capturing this stronghold and defeating Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton's forces stationed there.

The campaign consisted of many important naval operations, troop maneuvers, failed initiatives, and eleven distinct battles from December 26, 1862, to July 4, 1863. Military historians divide the campaign into two formal phases: operations against Vicksburg (December 1862 – January 1863) and Grant's operations against Vicksburg (March – July 1863).

Grant initially planned a two-pronged approach in which half of his army, under Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, would advance to the Yazoo River and attempt to reach Vicksburg from the northeast, while Grant took the remainder of the army down the Mississippi Central Railroad. Both of these initiatives failed. Grant conducted a number of "experiments" or expeditions—Grant's bayou operations—that attempted to enable waterborne access to the Mississippi south of Vicksburg's artillery batteries. All five of these initiatives failed as well. Finally, Union gunboats and troop transport boats ran the batteries at Vicksburg and met up with Grant's men who had marched overland in Louisiana. On April 29 and April 30, 1863, Grant's army crossed the Mississippi and landed at Bruinsburg, Mississippi. An elaborate series of demonstrations and diversions fooled the Confederates and the landings occurred without opposition. Over the next 17 days, Grant maneuvered his army inland and won five battles, captured the state capital of Jackson, Mississippi, and assaulted and laid siege to Vicksburg.

After Pemberton's army surrendered on July 4 (one day after the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg), and when Port Hudson surrendered to Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks on July 9, Texas and Arkansas were effectively cut off from the Confederacy, and the Mississippi River was once again open for northern commerce to reach the Gulf of Mexico, and as a supply line for the Union Army. Grant's Vicksburg campaign is studied as a masterpiece of military operations and a major turning point of the war.

Background

Military situation

| Army commanders (Vicksburg campaign) |

|---|

|

Vicksburg was strategically vital to the Confederates. Jefferson Davis said, "Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South's two halves together."[4] While in their hands, it blocked Union navigation down the Mississippi; together with control of the mouth of the Red River and of Port Hudson to the south, it allowed communication with the states west of the river, upon which the Confederates depended extensively for horses, cattle and reinforcements. The natural defenses of the city were ideal, earning it the nickname "The Gibraltar of the Confederacy". It was located on a high bluff overlooking a horseshoe-shaped bend in the river, De Soto Peninsula, making it almost impossible to approach by ship. North and east of Vicksburg was the Mississippi Delta (sometimes known as the Yazoo Delta), an area 200 miles (320 km) north to south and up to 50 miles (80 km) across, which has been described by geographer Warren E. Grabau as an "astonishingly complex network of intersecting waterways", some of which were navigable by small steamboats. The regions between modern rivers and bayous formed closed basins called backswamps, of which Grabau judged, "Whether permanently flooded or not, the backswamps were, for all practical purposes, untamed wildernesses, utterly impassable by a man on horseback or by any form of wheeled vehicle, and very difficult even for a man on foot."[5] About twelve miles (19 km) up the Yazoo River were Confederate batteries and entrenchments at Haynes Bluff. The Louisiana land west of Vicksburg was also difficult, with many streams and poor country roads, widespread winter flooding, and it was on the opposite side of the river from the fortress.

The city had been under Union naval attack before. Admiral David Farragut moved up the river after his capture of New Orleans and on May 18, 1862, demanded the surrender of Vicksburg. Farragut had insufficient troops to force the issue, and he moved back to New Orleans. He returned with a flotilla in June 1862, but their attempts (June 26–28) to bombard the fortress into surrender failed. They shelled Vicksburg throughout July and fought some minor battles with a few Confederate vessels in the area, but their forces were insufficient to attempt a landing, and they abandoned attempts to force the surrender of the city. Farragut investigated the possibility of bypassing the fortified cliffs by digging a canal across the neck of the river's bend, the De Soto Peninsula. On June 28, Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams, attached to Farragut's command, began digging work on the canal by employing local laborers and some soldiers. Many of the men fell victim to tropical diseases and heat exhaustion, and the work was abandoned by July 24. (Williams was killed two weeks later in the Battle of Baton Rouge).[6]

In the fall of 1862, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck was promoted from command of the Western Theater to General-in-Chief of all Union armies. On November 23, he indicated to Grant his preference for a major move down the Mississippi to Vicksburg; in Halleck's style, he left considerable initiative to design a campaign, an opportunity that the pugnacious Grant seized. Halleck has received criticism for not moving promptly overland from Memphis, Tennessee, to seize Vicksburg during the summer when he was in command on the scene. He believed that the Navy could capture the fortress on its own, not knowing that the naval force was insufficiently manned with ground troops to finish the job. What might have achieved success in the summer of 1862 was no longer possible by November because the Confederates had amply reinforced the garrison by that time. Also, reliable navigation on the river was seasonal, and the natural fall in the level of the river during the fall and winter months limited the utility of shipping, the usable draft of riverboats, and the quantity of men, supplies, and equipment, they could transport.

Grant's army marched south down the Mississippi Central Railroad, making a forward base at Holly Springs. He planned a two-pronged assault in the direction of Vicksburg. His principal subordinate, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, was to advance down the river with four divisions (about 32,000 men) and Grant would continue with the remaining forces (about 40,000) down the railroad line to Oxford, where he would wait for developments, hoping to lure the Confederate army out of the city to attack him in the vicinity of Grenada, Mississippi.

On the Confederate side, forces in Mississippi were under the command of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, an officer from Pennsylvania who chose to fight for the South. Pemberton had approximately 12,000 men in Vicksburg and Jackson, Mississippi, and Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had approximately 24,000 at Grenada.

Meanwhile, political forces were at work. President Abraham Lincoln had long recognized the importance of Vicksburg; he wrote "Vicksburg is the key. ...The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket."[7] Lincoln also envisioned a two-pronged offensive, but one up and down the river. Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand, a War Democrat politician, had convinced Lincoln that he could lead an army down the river and take Vicksburg. Lincoln approved his proposal and wanted Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks to advance up river from New Orleans at the same time. McClernand began organizing regiments, sending them to Memphis. Back in Washington, D.C., Halleck was nervous about McClernand and gave Grant control of all troops in his own department. McClernand's troops were split into two corps, one under McClernand, the other under Sherman. McClernand complained but to no avail. Grant appropriated his troops, one of several maneuvers in a private dispute within the Union Army between Grant and McClernand that continued throughout the campaign.

Battles in the operations against Vicksburg, December 1862 – January 1863

The "operations against Vicksburg" phase of the Vicksburg campaign comprises the following battles:

Chickasaw Bayou (December 26–29, 1862)

Sherman disembarked with three divisions at Johnson's Plantation on the Yazoo River to approach the Vicksburg defenses from the northeast. On December 27, the Federals pushed their lines forward through the swamps toward the Walnut Hills, which were strongly defended. On December 28, several futile attempts were made to get around these defenses. On December 29, Sherman ordered a frontal assault, which was repulsed with heavy casualties, and then withdrew.[8]

During this period, the overland half of Grant's offensive was failing. His lines of communication were disrupted by raids by Van Dorn and Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who destroyed his large supply depot at Holly Springs. Unable to subsist his army without these supplies, Grant abandoned his overland advance.

In early January, McClernand arrived at Memphis with the corps he had recruited (the XIII Corps under Brig. Gen. George W. Morgan) and commenced his operation down the Mississippi. On January 4, he ordered Sherman to attach his XV Corps to the expedition, calling his combined 32,000-man force the Army of the Mississippi. This was a direct provocation against Grant, but Sherman acceded to the senior officer. Sherman suggested beginning with a combined land and naval movement against Fort Hindman, on the Arkansas River at Arkansas Post, 50 miles up the Arkansas from its confluence with the Mississippi, a base from which Confederate gunboats were attacking Union shipping on the river. The expedition started without notifying Grant.[9]

Arkansas Post (January 9–11, 1863)

Union boats under Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter began landing troops near Arkansas Post in the evening of January 9. The troops started up river towards Fort Hindman. Sherman's corps overran Confederate trenches, and the defenders retreated to the protection of the fort and adjacent rifle-pits. Porter, on January 10, moved his fleet towards Fort Hindman and bombarded it, withdrawing at dusk. Union artillery fired on the fort from positions across the river on January 11, and the infantry moved into position for an attack. Union ironclads commenced shelling the fort and Porter's fleet passed it to cut off any retreat. As a result of this envelopment, and the attack by Morgan's troops, the Confederate command surrendered in the afternoon. Although Union losses were high and the victory did not contribute to the capture of Vicksburg, it did eliminate one more impediment to Union shipping on the Mississippi.[10]

Grant was not happy to learn that McClernand had conducted the operation without his approval, considering it a distraction from his main objective of Vicksburg, but since it had been successful and his ally Sherman had suggested it, he took no punitive action. However, he ordered McClernand back to the Mississippi and assumed personal command of the campaign on January 13 at Milliken's Bend, 15 miles northwest of Vicksburg.

Grant's bayou operations, January–March 1863

That winter, Grant conducted a series of initiatives to approach and capture Vicksburg,[11] termed "Grant's bayou operations". Their general theme was to use or construct alternative waterways so that troops could be positioned within striking distance of Vicksburg, without requiring a direct approach on the Mississippi under the Confederate guns.

Grant's Canal

The Williams Canal across De Soto Peninsula had been abandoned by Adm. Farragut and Brig. Gen. Williams in July 1862, but it had the potential to offer a route downriver that bypassed Vicksburg's guns. In late January 1863, Sherman's men, at the urging of Grant—who was advised by the navy that President Lincoln liked the idea—resumed digging. Sherman derisively called the work "Butler's Ditch" (since it was Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler who had sent Williams upriver to do the work), which was barely 6 feet wide by 6 feet deep. Grant, undoubtedly influenced by Lincoln's continual inquiries as to the status of the canal, ordered Sherman to expand the canal to 60 feet wide and 7 feet deep and the effort became known as Grant's Canal. It was not properly engineered based upon the hydrology of the Mississippi River, however, and a sudden rise in the river broke through the dam at the head of the canal and flooded the area. The canal began to fill up with back water and sediment. In a desperate effort to rescue the project, two huge steam-driven dipper dredges, Hercules and Sampson, attempted to clear the channel, but the dredges were exposed to Confederate artillery fire from the bluffs at Vicksburg and driven away. By late March, work on the canal was abandoned. (Remnants of about 200 yards of Grant's Canal are maintained by the Vicksburg National Military Park in Louisiana).[12]

Lake Providence expedition

Grant ordered Brig. Gen. James B. McPherson to construct a canal of several hundred yards from the Mississippi to Lake Providence, northwest of the city. This would allow passage to the Red River, through Bayous Baxter and Macon, and the Tensas and Black Rivers. Reaching the Red River, Grant's force could join with Banks at Port Hudson. McPherson reported that the connection was navigable on March 18, but the few "ordinary Ohio River boats" that had been sent to Grant for navigation of the bayous could only transport 8,500 men. The boats through Lake Providence increased the Union soldiers to a force of 30,000 and provided the field commander the flexibility of a 4:1 advantage, potentially more than enough to ensure a successful siege of Port Hudson. Although this was the only one of the bayou expeditions to successfully bypass the Vicksburg defenses, historian Ed Bearss diminishes this exploit as the "Lake Providence Boondoggle".[13]

Yazoo Pass expedition

The next attempt was to get to the high ground of the loess bluffs above Hayne's Bluff and below Yazoo City by blowing up the Mississippi River levee near Moon Lake, some 150 miles (240 km) above Vicksburg, near Helena, Arkansas, and following the Yazoo Pass (an old route from Yazoo City to Memphis, which was curtailed by the 1856 levee construction that sealed off the Pass from the Mississippi River to Moon Lake) into the Coldwater River, then to the Tallahatchie River, and finally into the Yazoo River at Greenwood, Mississippi. The dikes were blown up on February 3, beginning what was called the Yazoo Pass Expedition. Ten Union boats, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Watson Smith, with army troops under the command of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss, began moving through the pass on February 7. But low-hanging trees destroyed anything on the gunboats above deck and Confederates felled more trees to block the way. These delays allowed the Confederates time to quickly construct Fort Pemberton near the confluence of the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha Rivers near Greenwood, Mississippi, which repulsed the naval force on March 11, March 14, and March 16. The Union effort collapsed in early April.[14]

Steele's Bayou expedition

Admiral Porter started an effort on March 14 to go up the Yazoo Delta via Steele's Bayou, just north of Vicksburg, to Deer Creek. This would outflank Fort Pemberton and allow landing troops between Vicksburg and Yazoo City. Confederates once again felled trees in their path, and willow reeds fouled the boats' paddlewheels. This time the Union boats became immobilized, and Confederate cavalry and infantry threatened to capture them. Sherman sent infantry assistance to repel the Confederates bedeviling Porter, but Porter's approach was abandoned as too difficult.[15]

Duckport Canal

Grant's final attempt was to dig another canal from Duckport Landing to Walnut Bayou, aimed at getting lighter boats past Vicksburg. By the time the canal was almost finished, on April 6, water levels were declining, and none but the lightest of flatboats could get through. Grant abandoned this canal and started planning anew.[16]

From December through March, including Chickasaw Bayou and the Mississippi Central advance, seven initiatives, or "experiments", by Grant had failed. Grant claimed in his memoirs that he had undertaken these experiments primarily to keep his troops busy during the flooded and disease-laden winter months and that he had had no expectation of success. This claim is contradicted by correspondence from Grant at the time.[citation needed]

Plan for the 1863 campaign and initial movements

All of the bayou operations were failures, but Grant was well known for his stubborn determination and would not quit. His final option was bold but risky: March the Union army down the west side of the Mississippi, cross the river south of Vicksburg, and either attack Vicksburg from the south and the east or join forces with Banks, capture Port Hudson, and then together reduce Vicksburg. Porter would have to sneak past the guns to get sufficient gunboats and transport ships south of the city. Once they had completed the downstream passage, they would not be able to return past Vicksburg's guns because the river current would slow them too much.

On March 29, McClernand set his troops to work building bridges and corduroy roads. They filled in the swamps in their way as well, and by April 17 they had a rough, tortuous 70-mile (110 km) road from Milliken's Bend to the proposed river crossing at Hard Times, Louisiana, below Vicksburg.

On April 16, a clear night with no moon, Porter sent seven gunboats and three empty troop transports loaded with stores to run the bluff, taking care to minimize noise and lights. But the preparations were ineffective. Confederate sentries sighted the boats, and the bluff exploded with massive artillery fire. Fires were set along the banks to improve visibility. The Union gunboats answered back. Porter observed that the Confederates mainly hit the high parts of his boats, reasoned that they could not depress their guns, and had them hug the east shore, right under Confederate cannon, so close he could hear their commanders giving orders, shells flying overhead. The fleet survived with little damage; thirteen men were wounded and none killed. The Henry Clay was disabled and burned at the water's edge. On April 22, six more boats loaded with supplies made the run; one boat did not make it, though no one was killed. The crew floated downstream on the boat's remnants.

The final piece of Grant's strategy was to divert Pemberton's attention from the river crossing site that the Union troops would use. Grant chose two operations: a feint by Sherman against Snyder's Bluff, Mississippi, north of Vicksburg (see the Battle of Snyder's Bluff below), and a daring cavalry raid through central Mississippi by Col. Benjamin Grierson, known as Grierson's Raid. Both were eminently successful. Of Sherman's feint, Grant writes:

My object was to compel Pemberton to keep as much force about Vicksburg as I could, until I could secure a good footing on high land east of the river. The move was eminently successful and, as we afterwards learned, created great confusion about Vicksburg and doubts about our real design.

Grierson was able to draw out significant Confederate forces to chase him, and Pemberton's defenses were dispersed too far around the state. (Pemberton was also wary of Nathaniel Banks's impending advance up the river from Baton Rouge to threaten Port Hudson.)[citation needed]. Of Grierson's raid, Grant writes:

It was at Port Gibson I first heard through a Southern paper of the complete success of Colonel Grierson, who was making a raid through central Mississippi...This raid was of great importance, for Grierson had attracted the attention of the enemy from the main movement against Vicksburg.

Opposing forces

Union

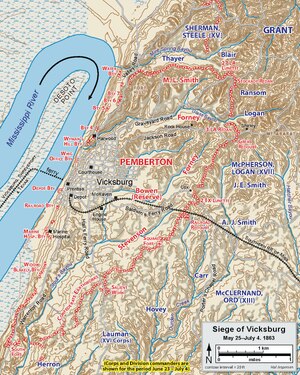

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Union Army of the Tennessee started the campaign with about 44,500 men,[17][18] which grew by July to 75,000. The army was composed of five corps: the XIII Corps, under Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand; the XV Corps, under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman; the XVII Corps, under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson; a three-division detachment of the XVI Corps, under Maj. Gen. Cadwallader C. Washburn; and a detachment from the District of Northeast Louisiana, under Brig. Gen. Elias S. Dennis. The IX Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, joined the army in mid-June.

Confederate

Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton's Confederate Army of Mississippi, approximately 30,000 men, consisted of five divisions, under Maj. Gens. William W. Loring, Carter L. Stevenson, John H. Forney, Martin L. Smith, and John S. Bowen.

General Joseph E. Johnston's forces in Raymond and Jackson, Mississippi, about 6,000 men, were elements of his Department of the West, including the brigades of Brig. Gen. John Gregg, and Col. Peyton H. Colquitt. Loring's division had joined Johnston on May 17 after the retreat from Champion Hill and Johnston was further reinforced by Brig. Gen. William H.T. Walker's division, and the cavalry division of Brig. Gen. William Hicks Jackson in late May, followed by the divisions of Maj. Gens. John C. Breckinridge and Samuel G. French in June, bringing his total strength to about 36,000 when Vicksburg surrendered.[1][19]

Battles in Grant's operations against Vicksburg, April – July 1863

The "Grant's operations against Vicksburg" phase of the Vicksburg campaign comprises the following battles:

Grand Gulf (April 29, 1863)

Admiral Porter led seven ironclads in an attack on the fortifications and batteries at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, with the intention of silencing the Confederate guns and then securing the area with troops of McClernand's XIII Corps who were on the accompanying transports and barges. The attack by the seven ironclads began at 8 a.m. and continued until about 1:30 p.m. During the fight, the ironclads moved within 100 yards of the Confederate guns and silenced the lower batteries of Fort Wade. The Confederate upper batteries at Fort Cobun remained out of reach and continued to fire. Due to the strong Confederate resistance, Grant and Porter decided it was not feasible to make an amphibious landing at Grand Gulf, but later landed at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, instead. The Union ironclads (one of which, the Tuscumbia, had been put out of action) and the transports temporarily drew off, but later that afternoon, while the angle of the sun interfered with Confederate aiming, Porter again sent his ships to Grand Gulf. While the ironclads screened them, the steamboats and barges ran the gauntlet. Meanwhile, Grant marched his men overland across Coffee Point to below the Gulf. After the transports had passed Grand Gulf, they embarked the troops at Disharoon's plantation and disembarked them on the Mississippi shore at Bruinsburg, below Grand Gulf. Grant landed 17,000 soldiers there, the largest amphibious operation in American military history until the Invasion of Normandy. The men immediately began marching overland towards Port Gibson, Mississippi, where, on May 1, they fought the Battle of Port Gibson with Bowen's Confederates. Bowen's right flank was driven in, and Bowen's men conducted a fighting withdrawal from the field.[20] On May 3, the Confederates abandoned the fortifications at Grand Gulf. The Confederates had won a hollow victory, since the loss at Grand Gulf caused just a slight change in Grant's offensive.[21]

Snyder's Bluff (April 29 – May 1)

To ensure that troops would not be withdrawn to Grand Gulf to assist Confederates there, a combined Union army-navy force feigned an attack on Snyder's Bluff. After noon on April 29, Lt. Cdr. K. Randolph Breese, with his eight gunboats and ten transports carrying Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair's division, inched up the Yazoo River to the mouth of Chickasaw Bayou where they spent the night. At 9 a.m., the next morning, the force, minus one gunboat, continued upriver to Drumgould's Bluff and engaged the enemy batteries. During the fighting, Choctaw suffered more than fifty hits, but no casualties occurred. Around 6 p.m., the troops disembarked and marched along Blake's Levee toward the guns. As they neared Drumgould's Bluff, a battery opened on them, creating havoc and casualties. The Union advance halted and, after dark, the men reembarked on the transports. The next morning, transports disembarked other troops. The swampy terrain and enemy heavy artillery fire forced them to retire. The gunboats opened fire again, about 3 p.m. on May 1, causing some damage. Later, the boats' fire slackened and stopped altogether after dark. Sherman had received orders to land his troops at Milliken's Bend, so the gunboats returned to their anchorages at the mouth of the Yazoo.[22]

Port Gibson (May 1)

Grant's army began marching inland from Bruinsburg. Advancing on the Rodney Road towards Port Gibson, they ran into Confederate outposts after midnight and skirmished with them for around three hours. After 3 a.m., the fighting stopped. Union forces advanced on the Rodney Road and a plantation road at dawn. At 5:30 a.m., the Confederates engaged the Union advance and the battle ensued. Federals forced the Confederates to fall back. The Confederates established new defensive positions at different times during the day, but they could not stop the Union onslaught and left the field in the early evening. This defeat demonstrated that the Confederates were unable to defend the Mississippi River line, and the Federals had secured their beachhead.[23]

At this point, Grant faced a decision. His original orders were to capture Grand Gulf and then proceed south to link up with Banks and reduce Port Hudson, after which their combined armies would return and capture Vicksburg. Unfortunately for Grant, such a course would put him under the command of the more senior major general and the credit for any success in the theater would go to Banks. Since Banks was occupied with operations on the Red River and had informed Grant that he was not ready to begin operations against Port Hudson within the next few days, Grant decided to move on his own against Vicksburg. He sent a message to Halleck about his intentions, knowing that it would take as many as eight days for Washington to receive the message and respond.

After the Union army seized the crossing at Grindstone Ford, any Confederate forces between the Big Bayou Pierre and the Big Black River were compromised. Realizing this, Bowen evacuated Grand Gulf and proceeded with all speed to Hankinson's Ford across the Big Black, barely escaping the Union trap. Grant's intention at this time was to move north over this same route and advance directly on Vicksburg. However, scouting parties that he sent out found that Pemberton had good defensive positions to the south of the city. Instead, he decided to break the city's supply line by seizing the railroad from Jackson to Vicksburg. He gave orders for his three corps (Sherman having arrived across the river) to advance over three separate routes to attack the railroad at Edwards Station (the westernmost objective, with McClernand's corps), Clinton (easternmost, with McPherson's) and Midway Station (center, with Sherman's).

Raymond (May 12)

On May 10, Pemberton ordered all reinforcements arriving at Jackson to march to Raymond, 20 miles (32 km) to the southwest. Brig. Gen. John Gregg's overstrength brigade, having endured a grueling march from Port Hudson, Louisiana, began marching to Raymond the next morning, arriving late in the afternoon of May 11. On May 12, Gregg's brigade moved to ambush a Union raiding party at Fourteen Mile Creek. The raiding party turned out to be Maj. Gen. John A. Logan's Division of the XVII Corps. Gregg decided to dispute the crossing of Fourteen Mile Creek and arrayed his men and artillery accordingly. As Logan's men approached, the Confederates opened fire, initially causing heavy casualties. Some Union troops broke, but Logan rallied a force to hold the line. Confederate troops attacked the line but were forced to retire. Additional Union troops arrived and counterattacked. Heavy fighting ensued that continued for six hours, but the overwhelming Union force prevailed. Gregg's men left the field. Although they lost the battle, they had held up a much superior Union force for a day. General Gregg, under orders to withdraw to Jackson in the face of a superior force, withdrew five miles (8 km) in the direction of Jackson to Mississippi Springs, Mississippi. This retrograde movement exposed the Southern Railroad of Mississippi to Union forces, thus severing the lifeline of Vicksburg.[24]

Despite McPherson's victory, the presence of Confederate forces attacking Grant's right flank caused him to reconsider his plan. He learned that Gen. Joseph E. Johnston was due in Jackson with reinforcements within the next couple of days, and there was a rumor that Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard would also arrive on the scene. In this situation, the Union army would be between enemy forces on each flank. Therefore, he chose to deal with the threat from the east first and ordered Sherman and McPherson to seize Jackson.

Jackson (May 14)

On May 9, Gen. Johnston received a dispatch from the Confederate Secretary of War directing him to "proceed at once to Mississippi and take chief command of the forces in the field". When he arrived in Jackson on May 13 from Middle Tennessee, he learned that two army corps—Sherman's and McPherson's—were advancing on Jackson and that Gregg had only about 6,000 troops available to defend the city. Johnston ordered the evacuation of Jackson, but Gregg was to defend Jackson until the evacuation was completed. By 10 a.m., both Union army corps were near Jackson and had engaged the enemy. Rain, Confederate resistance, and poor defenses prevented heavy fighting until around 11 a.m., when Union forces attacked in numbers and slowly but surely pushed the enemy back. In mid-afternoon, Johnston informed Gregg that the evacuation was complete and that he should disengage and follow. Soon after, the Union troops entered Jackson and had a celebration hosted by Grant, who had been traveling with Sherman's corps, in the Bowman House. They then burned part of the town, destroyed numerous factories, and cut the railroad connections with Vicksburg. Johnston's evacuation is seen as a mistake because he could, by late on May 14, have had 11,000 troops at his disposal and by the morning of May 15, another 4,000. The fall of the Mississippi state capital was a blow to Confederate morale.[25] Having broken the rail links, Grant temporarily abandoned the city to allow his troops to concentrate on Vicksburg.

Johnston retreated with most of his army up the Canton Road, but he ordered Pemberton to leave Edwards Station and attack the Federals at Clinton. Pemberton and his generals felt that Johnston's plan was dangerous and decided instead to attack the Union supply trains moving from Grand Gulf to Raymond. On May 16, however, Pemberton received another order from Johnston repeating his former directions. Pemberton had already started after the supply trains and was on the Raymond-Edwards Road with his rear at the crossroads one-third mile south of the crest of Champion Hill. Thus, when he ordered a countermarch, his rear, including his many supply wagons, became the vanguard of his force.

Champion Hill (May 16)

On May 16, about 7 a.m., the Union forces engaged the Confederates and the Battle of Champion Hill began. Pemberton's force drew up into a defensive line along a crest of a ridge overlooking Jackson Creek. Pemberton was unaware that one Union column was moving along the Jackson Road against his unprotected left flank. For protection, Pemberton posted Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee's men atop Champion Hill where they could watch for the reported Union column moving to the crossroads. Lee spotted the Union troops and they soon saw him. If this force was not stopped, it would cut the Confederates off from their Vicksburg base. Pemberton received warning of the Union movement and sent troops to his left flank. Union forces at the Champion House moved into action and emplaced artillery to begin firing. When Grant arrived at Champion Hill, around 10 a.m., he ordered the attack to begin. By 11:30 a.m., Union forces had reached the Confederate main line and about 1 p.m., they took the crest while the Confederates retreated in disorder. The Federals swept forward, capturing the crossroads and closing the Jackson Road escape route. One of Pemberton's divisions (Bowen's) then counterattacked, pushing the Federals back beyond the Champion Hill crest before their surge came to a halt. Grant then counterattacked, committing forces that had just arrived from Clinton by way of Bolton. Pemberton's men could not stand up to this assault, so he ordered his men from the field to the one escape route still open: the Raymond Road crossing of Bakers Creek. Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman's brigade formed the rearguard, and they held at all costs, including the loss of Tilghman. In the late afternoon, Union troops seized the Bakers Creek Bridge, and by midnight, they occupied Edwards. The Confederates were in full retreat towards Vicksburg.[26]

Big Black River Bridge (May 17)

The Confederate retreat reached Big Black River Bridge the night of May 16–17. Pemberton ordered Brig. Gen. Bowen, with three brigades, to man the fortifications on the east bank of the river and impede any Union pursuit. Three divisions of McClernand's corps moved out from Edwards Station on the morning of May 17. The corps encountered the Confederates behind breastworks and took cover as enemy artillery began firing. Union Brig. Gen. Michael K. Lawler formed his 2nd Brigade, Brig. Gen. Eugene A. Carr's Division, which surged out of a river meander scar, across the front of the Confederate forces, and into the enemy's breastworks, held by Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn's inexperienced East Tennessee Brigade. Confused and panicked, the Confederates began to withdraw across the Big Black on two bridges: the railroad bridge and the steamboat dock moored athwart the river. As soon as they had crossed, the Confederates set fire to the bridges, preventing close Union pursuit. The fleeing Confederates who arrived in Vicksburg later that day were disorganized. The Union forces captured approximately 1,800 troops at Big Black, a loss that the Confederates could ill afford.[27]

Siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4)

The Union army converged on Vicksburg, trapping Pemberton's force. Grant attempted two assaults to break through the strong Confederate fieldworks: May 19 and May 22. The latter assault initially achieved some success in McClernand's sector, but it was repulsed with 3,200 casualties. Johnston ordered Pemberton to evacuate the city and save his army, but Pemberton thought it impossible to withdraw safely. Johnston planned to attack Grant and relieve Pemberton but was unable to arrange it in time. Grant besieged the Confederate army. On July 4, after six weeks in which the soldiers and civilians of Vicksburg had no food supplies and were bombarded constantly, Pemberton surrendered the city and his army.[28]

In addition to Pemberton at his front, Grant had to be concerned with Confederate forces in his rear. He stationed one division in the vicinity of the Big Black River bridge and another reconnoitered as far north as Mechanicsburg, both to act as a covering force. By June 10, the IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, was transferred to Grant's command. This corps became the nucleus of a special task force whose mission was to prevent Johnston, gathering his forces at Canton, from interfering with the siege. Sherman was given command of this task force and Brig. Gen. Frederick Steele replaced him at the XV Corps on June 22. Johnston eventually began moving to relieve Pemberton and reached the Big Black River on July 1, but he delayed a potentially difficult encounter with Sherman until it was too late for the Vicksburg garrison, and then fell back to Jackson.[29]

Louisiana operations

During the siege of Vicksburg, three other battles took place in the vicinity:

Milliken's Bend (June 7)

In an effort to cut Grant's supply line during the siege, the Confederates attacked the Milliken's Bend supply area up the Mississippi. This was mainly defended by untrained black troops, who fought with inferior weaponry and finally repelled the Confederates with help from gunboats, although at significant cost; the defenders lost 652 to the Confederate 185.[30]

Goodrich's Landing (June 29–30)

After Union forces began occupying the Louisiana river parishes, thousands of escaped slaves flocked to them. The Federals, therefore, leased some plantations and put the freedmen to work growing cotton or other crops; the proceeds from the sale of the crops helped defray expenses for food, clothing, etc. African American troops were assigned to protect these plantations, releasing other troops to fight. Confederates, determined to recapture some of these freedmen and destroy the crops, undertook an expedition from Gaines's Landing, Arkansas, to Lake Providence. Although the Confederates disrupted these operations, destroyed much property, and captured many supplies and weapons, the raid was only a minor setback for the Union. The Confederates could cause momentary disturbances, but they were unable to effect any lasting changes.[31]

Helena (July 4)

Confederate Lt. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes's troops attacked Helena, Arkansas, in an attempt to relieve pressure on Vicksburg. Although the Confederates had more troops and did initially capture some of the fortifications, the Union forces repelled them.[32]

Aftermath

Although the Confederate killed and wounded in the battle and siege of Vicksburg were a relatively small 2,872, and Union 4,910, Grant captured his second Confederate army in its entirety (the first being at Fort Donelson): 29,495 surrendered.[33] Most of the Confederates were paroled. The Union also captured significant quantities of artillery, small arms, and ammunition. The full campaign, since March 29, claimed 10,142 Union and 9,091 Confederate killed and wounded.[34]

This was the second major blow to the Confederacy in the summer of 1863. On July 3, Gen. Robert E. Lee's invasion of the North collapsed at Gettysburg. On July 4, the Stars and Stripes rose over Vicksburg. To the Confederates, surrendering on Independence Day was a bitter defeat. Union troops behaved well, mixing with Confederates and giving rations to starving soldiers. Speculators who had been hoarding food for higher prices saw their stores broken open and the contents thrown on the streets for the starving rebels. In his Personal Memoirs, Grant observed, "The men of the two armies fraternized as if they had been fighting for the same cause."[35] But resentments lingered: allegedly tradition holds that the Fourth of July holiday was not celebrated by Vicksburg until World War II.[36] This claim has been challenged because large Fourth of July celebrations were being held by 1907.[37][38] The most significant result of the campaign was control of the Mississippi River, which the Union obtained completely after Port Hudson, which had been besieged by Banks since May 27, heard news of Vicksburg's fall and surrendered on July 9. The Confederacy was now cut in two; one week later, an unarmed ship arrived in Union-held New Orleans from St. Louis after an uneventful trip down the river. President Lincoln announced, "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea."[39]

Grant deployed Sherman and 50,000 troops against Johnston's 31,000 in Jackson. Johnston tried to lure Sherman into a frontal assault, but Sherman had seen the results of such at Vicksburg. He demurred and began surrounding the city. Johnston escaped with his army, which was more than Pemberton had achieved, but all of central Mississippi was now under Sherman's control. He used a subsequent operation against Meridian, Mississippi, as a harbinger of the scorched earth tactics he later employed in his March to the Sea through Georgia, and then South Carolina.

One of Grant's actions during the siege was to settle a lingering rivalry. On May 30, General McClernand wrote a self-adulatory note to his troops, claiming much of the credit for the soon-to-be victory. Grant had been waiting six months for him to slip, ever since they clashed early in the campaign, around the Battle of Arkansas Post. Grant finally relieved McClernand on June 18. McClernand's XIII Corps was turned over to Maj. Gen. Edward Ord. In May 1864, McClernand was restored to a command in remote Texas.[40]

Grant was the undisputed victor of the Vicksburg campaign. He was rewarded for his victory with a promotion to major general in the regular army, effective on July 4, 1863. He also received an unusual letter:

My dear General

I do not remember that you and I ever met personally. I write this now as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done the country. I wish to say a word further. When you first reached the vicinity of Vicksburg, I thought you should do, what you finally did—march the troops across the neck, run the batteries with the transports, and thus go below; and I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition, and the like, could succeed. When you got below, and took Port Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join Gen. Banks; and when you turned Northward East of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right, and I was wrong.

Yours very truly,

A. Lincoln[41]

Grant went on to rescue Union forces besieged at Chattanooga and then replaced Halleck as general in chief of all Union armies, with the recently re-activated rank of lieutenant general. Despite his ultimate success in winning the war, historians have often considered Vicksburg his finest campaign—imaginative, audacious, relentless, and a masterpiece of maneuver warfare. James M. McPherson called Vicksburg "the most brilliant and innovative campaign of the Civil War"; T. Harry Williams described it as "one of the classic campaigns of the Civil War and, indeed, of military history"; and the U.S. Army Field Manual 100–5 (May 1986) called it "the most brilliant campaign ever fought on American soil".[42]

Historian Steven E. Woodworth wrote that Pemberton "had a strong claim to the title of the most hated man in the South, certainly the most hated to wear a Confederate uniform". There were accusations that adequate supplies had been on hand and that it was only his treachery that caused the surrender. Even his friend, Confederate general Richard Taylor, wrote after the war that a large part of the population believed "He had joined the South for the express purpose of betraying it, and this was clearly proven by the fact that he surrendered on the 4th of July, a day sacred to the Yankees."[43][44] Davis maintained full confidence in Pemberton, pointing out that he would have been severely criticized and denounced if he had not attempted to defend Vicksburg, but had wound up with the same result by trying to do so. Still, Pemberton's unpopularity made it impossible for Davis to assign him another command after he returned to the Confederate army once he was exchanged. Eventually he resigned his rank of Lt. General to receive a commission as lieutenant colonel in command of the artillery defenses of Richmond.[45]

The blame for losing Vicksburg fell not only on John Pemberton, but on the overcautious Joseph E. Johnston. Jefferson Davis said of the defeat, "Yes, from a want of provisions inside and a General outside who wouldn't fight."[46]

See also

- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1863

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

- Armies in the American Civil War

- Commemoration of the American Civil War

- Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps

- Vicksburg National Military Park

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Dr. Christopher Gabel (2015). Staff Ride Handbook For The Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862 – July 1863. Golden Springs Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 9781782899358. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ a b National Park Service: Vicksburg National Military Park (Campaign, Siege and Defense of Vicksburg – General summary of Casualties, April 29 – July 4).

- ^ National Park Service: Confederate Parole Records

- ^ Winschel, p. 14.

- ^ Grabau, p. 19.

- ^ Ballard, pp. 46–62; Bearss, vol. I, p. 437; VNMP article on Grant's Canal.

- ^ Ballard, p. 24.

- ^ NPS Chickasaw Bayou.

- ^ Ballard, pp. 147–149.

- ^ NPS Arkansas Post.

- ^ Organization of the Army of the Tennessee, Major General Ulysses S. Grant, U. S. Army, commanding, January 31, 1863: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part 3, p. 23.

- ^ Bearss, vol. I, pp. 436–450; VNMP article on Grant's Canal.

- ^ Bearss, vol. I, pp. 467–478; Ballard, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Bearss, vol. I, pp. 479–548; Ballard, pp. 174–184; Eicher, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Bearss, vol. I, pp. 549–590; Ballard, pp. 184–188.

- ^ Ballard, p. 193.

- ^ Strength of the Department of the Tennessee, Major General Ulysses S. Grant, U. S. Army, commanding, April 30, 1863: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part 3, p. 249.

- ^ Organization of the Department of the Tennessee, Major General Ulysses S. Grant, U. S. Army, commanding, April 30, 1863: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part 3, pp. 250–259.

- ^ Dr. Christopher Gabel (2015). Staff Ride Handbook For The Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862 – July 1863. Golden Springs Publishing. pp. 170–171. ISBN 9781782899358. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 158–164.

- ^ "Bruinsburg Crossing (April 30 – May 1)". National Park Service. Retrieved 7 September 2018.; NPS Grand Gulf.

- ^ NPS Snyder's Bluff.

- ^ NPS Port Gibson.

- ^ NPS Raymond.

- ^ NPS Jackson.

- ^ NPS Champion Hill.

- ^ NPS Big Black River Bridge.

- ^ NPS Vicksburg.

- ^ Esposito, text for map 107.

- ^ NPS Milliken's Bend.

- ^ NPS Goodrich's Landing.

- ^ NPS Helena.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 173.

- ^ Ballard, pp. 398–399.

- ^ Grant, chapter XXXVIII, p. 38.

- ^ The claim is for example made in Ken Burns's miniseries The Civil War.

- ^ Waldrep, Christopher (2005). Vicksburg's Long Shadow: The Civil War Legacy Of Race And Remembrance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 247. ISBN 978-0742548688.

- ^ Historian Michael G. Ballard, in his Vicksburg campaign history, pp. 420-21, claims that this story has little foundation in fact. Although it is unknown whether city officials sanctioned the day as a local holiday, Southern observances of July 4 were for many years characterized more by family picnics than by formal city or county activities.

- ^ Ballard, p. 410.

- ^ Bearss, vol. III, pp. 875–879; Ballard, pp. 358–359; Korn, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Smith, p. 257.

- ^ Bonekemper, A Victor, Not a Butcher, p. 83.

- ^ Woodworth, Jefferson Davis and His Generals, p. 218.

- ^ David Zimring, To live and Die in Dixie: Native Northerners Who Fought for the Confederacy, Univ Tennessee Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1621901068; p. 262.

- ^ "StackPath".

- ^ McPherson, p. 637.

Bibliography

- Ballard, Michael B. Vicksburg, The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. The Campaign for Vicksburg. Vol. 1, Vicksburg is the Key. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1985. ISBN 0-89029-312-0.

- Bearss, Edwin C. The Campaign for Vicksburg. Vol. 2, Grant Strikes a Fatal Blow. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1986. ISBN 0-89029-313-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. The Campaign for Vicksburg. Vol. 3, Unvexed to the Sea. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1986. ISBN 0-89029-516-6.

- Bonekemper, Edward H. A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-89526-062-X.

- Catton, Bruce. The Centennial History of the Civil War. Vol. 3, Never Call Retreat. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965. ISBN 0-671-46990-8.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Gabel, Christopher R., Staff ride handbook for the Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862 – July 1863. Fort Leavenworth, Kan.: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2001. OCLC 47296103.

- Grabau, Warren E. Ninety-Eighty Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000. ISBN 1-57233-068-6.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. War on the Mississippi: Grant's Vicksburg Campaign. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4744-4.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Smith, Jean Edward. Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Solonick, Justin S. (7 April 2015). Engineering Victory: The Union Siege of Vicksburg. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-3392-9.

- Winschel, Terrence J. Vicksburg: Fall of the Confederate Gibraltar. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1-893114-00-5.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Jefferson Davis and His Generals: The Failure of Confederate Command in the West. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990. ISBN 0-7006-0461-8.

- National Park Service battle descriptions Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Memoirs and primary sources

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Organization of the Department of the Tennessee, Major General Ulysses S. Grant, U. S. Army, commanding, April 30, 1863: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part 3, pages 250–259.

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C. Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg: The Campaigns That Changed the Civil War. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4262-0510-1.

- Groom, Winston. Vicksburg, 1863. New York: Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26425-1.

- Huffstodt, James. Hard Dying Men: The Story of General W. H. L. Wallace, General Thomas E. G. Ransom, and the "Old Eleventh" Illinois Infantry in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Bowie, MD: Heritage Press. ISBN 1-55613-510-6.

- Miller, Donald L. Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019. ISBN 978-1-4516-4137-0.

- Smith, Timothy B. Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2004. ISBN 1-932714-00-6.

- Winschel, Terrence J. Triumph & Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Company, 1999. ISBN 1-882810-31-7.

- Woodworth, Steven E., ed. Grant's Lieutenants: From Cairo to Vicksburg. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001. ISBN 0-7006-1127-4.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

External links

- National Park Service, Vicksburg

- Vicksburg Battlefield: Battle maps Archived 2016-11-11 at the Wayback Machine, photos, history articles, and battlefield news (Civil War Trust)

- Animated map of the Vicksburg Campaign Archived 2017-03-24 at the Wayback Machine (Civil War Trust)

- First Vicksburg Campaign Archived 2007-07-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Animated history of the Siege of Vicksburg Archived 2013-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Confederate Command Failure at Vicksburg Archived 2012-07-24 at the Wayback Machine