Caracazo

| Caracazo | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Protests in Venezuela | |||

Top, left, right: Venezuelans cheering during the rioting; the looting of stores in Caracas; and police responding to a scene | |||

| Date | 27 February 1989 – 5 March 1989 (6 days) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Austerity measures | ||

| Methods |

| ||

| Resulted in | |||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 277 (government[neutrality is disputed]) 2,000–5,000 (independent est.[neutrality is disputed])[2][3][4] | ||

| Injuries | 2,000+[5] | ||

The Caracazo is the name given to the wave of protests,[6][7][8] riots and looting[9] that started on 27 February 1989 in the Venezuelan city of Guarenas, spreading to Caracas and surrounding towns following austerity measures from President Carlos Andrés Pérez. The weeklong clashes resulted in the deaths of hundreds, thousands by some accounts, mostly at the hands of security forces and the military.[2][3][10][11] The riots and the protests began mainly in response to the government's economic reforms and the resulting increase in the price of gasoline and transportation[6][7][9][2]

Etymology

The term "Caracazo", stems from the city's name, Caracas, and "-azo", which stems from another historic event, the Bogotazo, was a massive riot in Bogotá, recognized as having a crucial role in Colombia's history.[12] "Caracazo" is technically defined as the "Caracas smash" or "the big one in Caracas" based on Spanish dialect.

Background

During the presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez from 1973 to 1979, the political elite in Venezuela believed that the nation faced a near-unlimited supply of cashflow due to high oil prices at the time and his administration racked on large amounts of debt.[13] A fall in oil prices in the mid-1980s caused an economic crisis to take hold in Venezuela, and the country had accrued significant levels of debt. Nevertheless, the administration of President Jaime Lusinchi was able to restructure the country's debt repayments and offset an economic crisis but allow for the continuation of the government's policies of social spending and state-sponsored subsidies.[14]

Lusinchi's political party, the Democratic Action, was able to remain in power following the 1988 election, which saw Carlos Andrés Pérez return for his second tenure as president. Pérez based his campaign in his legacy of abundance during his first presidential period,[15] creating perceptions of being a populist leader as he promised that Venezuela would continue to modernize even though it was facing economic difficulties.[2] During his campaign, he heavily rejected liberalization policies,[16] describing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) staff as "genocide workers in the pay of economic totalitarianism" and its policies as a "bomb that only kills people."[2][13] Receiving 53% of the vote, Pérez demanded that Latin American debt be devalued by fifty percent and said that the region was a victim of international exploitation during celebrations after his inauguration.[2]

At the time his election, Venezuela's international reserves were at $300 million USD ($708 million USD in 2022), its national debt stood at $34 billion USD ($80 billion USD in 2022) and the poverty rate was at 70%.[13] Pérez reversed from his campaign rhetoric condemning the IMF[2][13][17] and decided to respond to the debt, public spending, economic restrictions and rentier state by liberalizing the economy upon taking office on 2 February 1989.[15] He announced on 16 February a technocratic cabinet and a group of shock therapy economic policies recommended by the IMF to fix macroeconomic imbalances known as El Gran Viraje (Template:Lang-en), called by detractors as El Paquetazo Económico (Template:Lang-en).[18] Among the austerity reforms unveiled were the reduction of fuel subsidies and the increase of public transportation fares by thirty percent.[7][2][13][19][20] He also took measures to decentralize and modernize the Venezuelan political system by the direct election of state governors, who had previously been appointed by the president. The most controversial part of the economic reform package was the reduction of the gasoline subsidies, which had long maintained domestic gasoline prices far beneath international levels and even the production costs. Pérez's package was rejected by all political parties, including his own, though he ignored their declinations.[7]

On the weekend of 25–26 February 1989, gasoline prices rose 100 per cent and the fuel price increase in turn needed an increase in public transportation fares of 30 per cent officially, and more in practice as some carriers refused to limit their prices to the official rate.[7] The increase was supposed to be implemented on 1 March 1989, but bus drivers decided to apply the price rise on 27 February, a day before payday in Venezuela.[7][19][20]

Timeline of protests and rioting

27 February

In the days prior to more intense protests, student demonstrations against neoliberalism began in Mérida and later spread to Caracas, where other social groups then began to protest against Pérez's policies.[21] Larger protests and rioting began on the morning of 27 February 1989 in Guarenas, a town in Miranda state about 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of Caracas, due to the increase in public transportation prices.[3][22][23] A lack of timely intervention by authorities, as the rank and file of the Caracas Metropolitan Police were on a labour strike, led the protests and rioting quickly spread to the capital and other towns across the country.[3][24][25][26]

Protests in the Lara state also started with students demonstrating against the increase of student fares and continued with public transport users in general. With no apparent authority presence or action, the crowd turned violent, the protest spread and turned into looting throughout the city. At midday Lara's governor called for the National Guard to disperse protests in Barquisimeto due to the president's presence, resulting with limited demonstrations in the area.[27] Pérez flew to Barquisimeto for a meeting of the Venezuelan Executives Association. According to Pérez's executive secretary, Ignacio Betancourt, he dismissed the warnings from ministers and other officials throughout the day. After being shown footage of lootings and demonstrations, Pérez dismissed it saying that events happened at noon and that the situation had calmed down. While meeting with the business executives, Pérez told his audience, "There is nothing to be alarmed about (...) We are going to take advantage of the crisis to generate well-being."[28] Pérez ordered to commence Plan Ávila,[29][30] a military contingency plan in place since the 1960s.[31]

By noon, one delivery truck was reported to have been looted in central Caracas and protesters blocked the Francisco Fajardo Highway, which connected east to west Caracas.[32] Students began to build barricades, which blocked the main thoroughfares in Caracas, and students of the Central University of Venezuela began to organize large protests against Pérez's new policies.[33] Branches, empty bottle crates and other obstacles were placed at each of the highway intersections to block traffic. Lorries thought to be transporting food were stopped by the crowd, the driver was non-violently detained and the cargo was unloaded and distributed, after which the driver was asked to park the vehicle across the carriageway. When the Metropolitan Police arrived later, they said that they had orders to not interfere.[34]

At 1:00 pm, police fired upon an increasingly large and agitated crowd near the Parque Central Complex, killing student Yulimar Reyes,[35] shooting her in the face with a shotgun at point-blank range.[34] 65 civilians were reported dead by 6:00 pm, with no severe casualties reported among authorities.[35]

That afternoon, Interior Affairs Minister Alejandro Izaguirre delivered a televised message in which the government attempted to announce that the situation was under control, but he was unable to conclude his speech, saying "I can't" and going off screen.[36] Through the night, some working class areas participated in parties with alcohol looted earlier in the day, including whisky, champagne and other food supplies.[37]

28 February

Groups of hundreds of protesters began to spread throughout Caracas, writing messages on walls that said "The people are hungry" and "No more deception." There were report of particularly vious attacks on stores owned by foreigners, namely Chinese, Lebanese and Portuguese immigrants, accusing them of hoarding supplies and of being responsible for the shortages. The demonstrations grew into an open revolt where nearly all social groups participated in the rioting.[37] At this time, Central Bank of Venezuela president Pedro Tinoco, Minister of Economy Eglée Iturbe de Blanco and Minister of Planning Miguel Rodríguez were at the IMF headquarters in Washington, D.C. signing a letter of intent to abide by the organization's economic prescriptions.[18][undue weight? – discuss]

Despite initial debate within the government over how to manage the situation, a heavy-handed approach was implemented as a state of emergency and martial law were imposed.[3] On February 28, a number of articles of the Constitution were suspended, including Article 60 (right to individual liberty and security), Article 62 (inviolability of the home), Article 66 (freedom of expression), Article 71 (right to gather publicly and privately), and Article 115 (right to peaceful protest).[38] According to army lieutenant Jesús Manuel Zambrano, he received instructions that day, saying "The order was: 'Go and neutralize that looting, how you do it is not my problem, but neutralize it'."[13] Some groups of troops allowed organized thefts to occur, letting people enter shops and take only essential items.[7][13] In public statements, Pérez spoke of defending the property of the wealthy while making polarized statements that poor individuals protesting–who were the majority in the nation–were "committed to violence" and were "subversives", resulting with the government rationalizing a violent response to demonstrations.[2] Despite the government blaming radical political groups for the rioting, such groups themselves were surprised by the escalation of unrest and some attempted to prevent looting.[13] Middle-class citizens responded to the protests by creating their own self-defense groups while the upper-class fled the situation in private jets due to fears of their property being destroyed.[2]

-

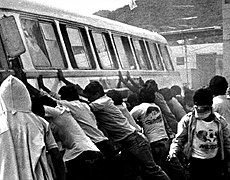

Rioters attempting to push over a bus

-

Looters running with stolen goods

-

Smoke billowing from fires throughout Caracas

-

Crowds gathered during the rioting

1 March

In Petare, army troops opened fire on a group of people, killing twenty.[7] Following the crackdown by authorities, gunfights between radical groups and the army began on 1 March, with the former believing that they were responding to armed political repression of their neighborhoods.[13] Ensuing firefights resulted in many bystanders being killed by "bullets from army troops and from sniping protesters".[3][1] Photojournalist Douglas Blanco questioned the presence of sharpshooters, saying "I was in the parts of El Valle and the 23 de Enero where supposedly there were sharpshooters, but that business sounds strange to me. You can't justify the shape in which those buildings in the 23 de Enero were left with the machine gunning by military and police. Do you have to destroy a building to eliminate a supposed sharpshooter?"[13] Velasco states that gunfights between radical militants and army troops did occur, though that engagements were not equal in intensity.[13] López Maya says that troops who entered 23 de Enero were young, inexperienced soldiers who fired automatic firearms indiscriminately at apartment blocks, killing unarmed residents inside.[7]

2 March

On 2 March, reporter Fabricio Ojeda wrote "In the morning, following the second night of curfew, those who descended from the barrios to go to work tripped over bodies shot up during the curfew."[13] Before curfew, José Calixto Blanco was shot in the face by troops at 2:00pm.[13] That day, President Pérez flew in a helicopter from Miraflores Palace with the protection of a second attack helicopter to observe scenes of the Caracazo and upon his return to the palace, he publicly declared "There's normalcy in the city. I return very satisfied with the flyover I have made. All of the city, all the barrios are in complete normalcy."[13] Reporters noted that he made this statement as gunfire could be heard within the palace from nearby neighborhoods.[13]

3 March

During his first appearance among the foreign press, Pérez described the Caracazo as actions "against the rich" as a result of inequality.[13] Protests in other large cities besides Caracas had largely subsided.[7] At 3:00pm, army reservist Carlos H. Cuñar was shot by troops while leaving the 23 de Enero neighborhood to buy groceries, later dying after he drove himself to a hospital.[13] By nightfall, militants in Zona Central who had been clashing with troops, began to run out of ammunition.[13]

Pérez spoke with U.S. President George H. W. Bush, who offered Pérez a US$450 million emergency loan. Pérez thanked Bush and asked him to support a change in debt policy toward Latin America, saying "I want to tell you if there is no change in [international] debt policy then whatever we may do here may be useless".[This quote needs a citation] Pérez told Bush that he had sent him a letter several days earlier and that he would appreciate it if he would read it.[39]

4 March

In the morning, troops entered homes to search for armed individuals.[13] As tensions eased, troops began to sweep through neighborhoods collecting appliances and cash registers and informing citizens that if they provided a certificate of purchase, the items would be returned.[1] Citizens began to be observed in the streets participating in daily life and some businesses reopened.[7] At this time, cemeteries began to grow crowded as individuals gathered to bury their loved ones who were killed earlier in the week.[7]

5 March

The final documented death of the Caracazo was Napoleón Soto Vilera after being shot in the head from by an individual at the Naval Observatory near Sierra Maestra.[13]

Aftermath and consequences

The Pérez government's response was described as a massacre.[13][17][40] Members of the National Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services (DISIP) were reported to have beaten protesters with baseball bats and pipes while they performed interrogations.[7]

One army lieutenant, Francisco Espinoza Guyón, said of orders received during the Caracazo:[13]

No one gave me a direct order to shoot to kill, but they did tell us that constitutional rights were suspended and that, if we needed to use our weapons to repress a looting, we were authorized to do so because nothing was going to happen to us. In other words, maybe they didn't explicitly order us to kill, but they did insinuate that if we needed to, it was within the rules of engagement to do so.

The IACHR said that a "disproportionate use of force" was especially used in impoverished areas.[13] Poor areas faced increased violence during the riots, with authorities firing indiscriminately throughout neighborhoods and dragging some individuals out of their homes for summary executions.[7][17] It was common to see bodies spread throughout the streets for hours during the protests.[13] Estimates from the Comité de Familiares de Víctimas del Caracazo state that 97% people who died during the Caracazo were killed in their homes.[17] In 23 de Enero, heavy repression was reported and bullet holes from the crackdowns were visible decades later in 2014.[13][17]

The initial official pronouncements stated that 276 people had died,[23] though the Pérez administration attempted to block investigations.[17] Of the deaths, two soldiers and one police officer were reported dead.[13] After hundreds of unmarked graves were found in the following months,[13] many estimates put the number at above 2,000[4] and up to 5,000.[2] Shortages of coffins were reported[17][1] and morgues were so overfilled with dead that workers had to explain to family members searching for loved ones that bodies were simply discarded in trash bags.[17] A mass grave was discovered a year later at El Cementerio de Sur where 68 bodies alone were found placed in plastic bags.[17]

During the protests, citizens in poor areas destroyed their own local commercial facilities, with food markets so damaged that their food distribution system was ruined.[1] Rioters destroyed properties indiscriminately, with no motives related to initial protests, and many had to line up at government food distribution centers since markets were destroyed by rioters.[1] Constitutional rights were not completely restored until March 22, and in the interim, there was no official decree or resolution to define how government authority would be exercised in the absence of such rights.[38] Insurance estimates of damage caused during the rioting were $90 million USD ($120 million CAD) in 1989, or $212 million USD in 2022.[1]

Political instability

The clearest consequence of the Caracazo was political instability. According to Velasco, the Caracazo is "[w]idely held as a turning point in Venezuelan history" and that it "exposed a deep fissure in the social pact between political elites and the electorate established in the wake of the 1958 democratic revolution that ousted Pérez Jiménez."[13] Strønen makes a similar assessment, saying "El Caracazo made it clear that the illusion of a social contract between the poor and the rest of society was irrevocably compromised. From that moment on, the popular sectors become increasingly radicalized, which explains the massive support for the attempted coup led by Chávez."[17]

In February 1990, the army was called to contain similar riots in Puerto La Cruz and Barcelona and again in June, when rising of transportation costs ended in riots in Maracaibo and other cities. The reforms were modified.[citation needed]

Hugo Chávez recognized the Caracazo as the beginning of his Bolivarian Revolution.[41] As part of the government's security forces, members of Chávez's MBR-200 allegedly participated in the crackdown;[42] Chávez himself was sick that day with measles.[43] The MBR-200, which in 1982 had promised to depose the bipartisanship governments,[44] repudiated the Caracazo and accelerated its preparation for a coup d'état against the Perez government.[45][page needed] Throughout the 1990s, MBR-200 participated in anti-austerity protests.[6] In 1992, there were two attempted coups in February and November. Pérez was later accused of corruption and removed from the presidency. Chávez, an organiser of one of the coups, was found guilty of sedition and incarcerated, though he was subsequently pardoned by Pérez's successor, Rafael Caldera.[45][page needed] MBR-200, Radical Cause and Movement Towards Socialism consolidated their political objectives into the Fifth Republic Movement,[6] with Chávez winning the 1998 Venezuelan presidential election.

Investigations

Shortly after the Caracazo, the Minister of Defense said that 277 individuals were killed.[7] A commission was established[when?] in the Venezuelan Congress to investigate the events during the Caracazo and voted for a report that concluded that 277 people were killed as well. The votes included that of José Vicente Rangel, a prominent critic of Carlos Andrés Pérez's government[46]

In 1998, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights condemned the government's action and referred the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In 1999, the Court heard the case and found that the government had committed violations of human rights, including extrajudicial killings. The Venezuelan government, by then headed by Chávez, did not contest the findings of the case and accepted full responsibility for the government's actions.[23]

Venezuelan attorney general Luisa Ortega Díaz ordered Pérez's extradition from the United States in 2009 as a result of his government's violent response during the Caracazo.[47]

In August 2009, Defense Minister Italo del Valle Alliegro was charged in relation to the Caracazo.[48] In July 2010, the Supreme Court overturned an appeal court ruling, which had declared the case covered by a statute of limitations.[49]

Analysis

According to writers such as Elizabeth Burgos, Milagros Socorros and Dámaso Jiménez, as well as Carlos Julio Peñaloza (a general at the time of the Caracazo), Cuban agents might have entered Venezuela during Carlos Andrés Pérez's inauguration ceremony, which was attended by Fidel Castro, and may have waited for unrest to occur in Venezuela so they could exacerbate political tensions.[50][51]

In Current History a month after the rioting, Judith Ewell said that "foreign bankers ... forced on Venezuela the most stringent debt-repayment terms in Latin America."[52] Strønen wrote that Pérez's reforms were the "last straw" for disenchanted groups and that, regarding the Caracazo, "The distance between the governing elites and the impoverished masses had become so wide that the authorities never saw it coming."[17] Lower class citizens were affected by shortages at the time, with many basic good missing from store shelves while people had to wait in lines outside of stores.[53][54] Economist Héctor Silva Michelena, who had described Venezuela's democracy in the 1970s as an "illusion" based on oil dependency, warned shortly after Pérez's announcement that social conditions for a "grave social explosion" were likely.[13] López Maya writes that Pérez performed "a serious political miscalculation", saying that this is supported by his continuous denial of his policies being responsible for the unrest.[7]

In popular culture

Román Chalbaud's 2005 homonymous film, El Caracazo, features an account of the events.[55]

The Venezuelan rock band La Vida Bohème also sings about the Caracazo.[55]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Riots leave Venezuela short of coffins; Up to 700 reported dead while hospitals say most of the injured were shot: B1". The Gazette. 5 March 1989.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k R. Guy, Emerson (2011). "A Bolivarian People: Identity politics in Hugo Chávez's Venezuela". Humanities Research. 17 (1). Canberra: Australian National University: 87–111.

- ^ a b c d e f Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, Venezuela, One-sided Violence, Government of Venezuela – civilians, http://www.ucdp.uu.se/gpdatabase/gpcountry.php?id=167®ionSelect=5-Southern_Americas# Archived 2014-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Crisp, Brian F. (1998), "Presidential Decree Authority in Venezuela", in John M. Carey and Matthew Soberg Shugart (eds, 1998), Executive decree authority, Cambridge University Press. p157

- ^ UN, Venezuela: Wound Still Gaping 20 Years after ‘Caracazo’, By Humberto Márquez, Caracas, Feb 27 2009 (IPS, http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/02/venezuela-wound-still-gaping-20-years-after-lsquocaracazorsquo/

- ^ a b c d Almeida, Paul; Pérez Martín, Amalia (2022). Collective Resistance to Neoliberalism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108981873.

Caracazo anti-neoliberal uprising

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p López Maya 2003.

- ^ Kingsbury, Donald (December 2013). "Between Multitude and Pueblo: Venezuela's Bolivarian Revolution and the Government of Un-governability". New Political Science. 35 (4): 567–585. doi:10.1080/07393148.2013.848702. ISSN 0739-3148. S2CID 144593260.

the caracazo—an anti-neoliberal uprising and massacre in 1989

- ^ a b Venezuela exhumes unnamed dead in riot investigation, Reuters, 22 September 2009.

- ^ UN, Venezuela: Wound Still Gaping 20 Years after ‘Caracazo’, By Humberto Márquez, Caracas, Feb 27 2009 (IPS), http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/02/venezuela-wound-still-gaping-20-years-after-lsquocaracazorsquo/

- ^ Amnesty International, March 1990, Reports of Arbitrary Killings and Torture:, February/March 1989, AI Index: AMR 53/02/90, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr53/002/1991/en/

- ^ Minster, Christopher. “Colombia's Legendary Riot of 1948.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 24 July 2019, www.thoughtco.com/the-bogotazo-april-9-1948-2136619.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Velasco 2015.

- ^ Barcelona Centre for International Affairs, Jaime Lusinchi, (Spanish) http://www.cidob.org/es/documentacion/biografias_lideres_politicos/america_del_sur/venezuela/jaime_lusinchi#2

- ^ a b Márquez & Sanabria 2018, p. 131

- ^ Fastenberg, Dan (10 January 2011). "Carlos Andrés Pérez". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Strønen, Iselin Åsedotter (2017), "Understanding the Bolivarian Revolution from Below", Grassroots Politics and Oil Culture in Venezuela, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 57–83, ISBN 978-3-319-59506-1,

the el Caracazo massacre in 1989

- ^ a b Lander, Edgardo; Fierro, Luis A. (July 1996). "The Impact of Neoliberal Adjustment in Venezuela, 1989-1993". Latin American Perspectives. 23 (3): 50–73. doi:10.1177/0094582X9602300304. ISSN 0094-582X. S2CID 143947955.

- ^ a b Márquez & Sanabria 2018, p. 132

- ^ a b Rivero 2011, p. 102

- ^ López Maya 2003, p. 20

- ^ Velasco 2015, p. 194

- ^ a b c El Caracazo Case, Judgment of 11 November 1999, Inter-American Court of Human Rights, accessed 1 May 2007

- ^ Velasco 2015, p. 289: "An ongoing strike among the rank and file of the Metropolitan Police, regarding the body's leadership structure, had delayed intervention on 27 February"

- ^ Rivero, Mirtha (2010). "10". La Rebelión de los Náufragos. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Alfa. p. 109. ISBN 978-980-354-295-5.

- ^ López Maya 2003, p. 8

- ^ López Maya 2003, p. 9

- ^ Velasco 2015, p. 198

- ^ Nelson, Brian A. (Fall 2007). "One Crowded Hour". Virginia Quarterly Review.

- ^ TalCual, Opinión (15 November 2021). "Del plan Ávila al plan Zamora, por Beltrán Vallejo". Tal Cual (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Velasco 2015, p. 213

- ^ Velasco 2015, p. 195: "By noon, a truck carrying groceries lay lootes, while demonstrators stopped traffic in the nearby Francisco Fajardo highway connecting east and west Caracas"

- ^ López Maya 2003, p. 7

- ^ a b López Maya 2003, p. 8

- ^ a b Velasco 2015, p. 195

- ^ "Muere Alejandro Izaguirre, ministro de Interior venezolano durante el 'Caracazo'". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ a b López Maya 2003, p. 10: "As in similar urban uprisings elsewhere, cases were reported of particularly vicious attacks on shops owned by foreigners, in this case Chinese, Lebanese and Portuguese immigrants, on the grounds that they were responsible for the shortages because they had been hoarding supplies"

- ^ a b Crisp, Brian F. (1998), "Presidential Decree Authority in Venezuela", in John M. Carey and Matthew Soberg Shugart (eds, 1998), Executive decree authority, Cambridge University Press. p150

- ^ Bush Presidential Library, 3 March 1989, Memcons and Telcons, https://bush41library.tamu.edu/files/Press--Meetings%20with%20Foreigners%201989.pdf

- ^ Massacres in Venezuela: Los Maniceros Massacre, Caracazo, Massacre of El Amparo, Yumare Massacre. 2010. ISBN 9781158269556.

- ^ "Hugo Chavez death reports wrong, says vice-president". The Telegraph. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

'Caracazo', the massacre of hundreds of people in 1989

- ^ Nelson, Brian A. (2009). The silence and the scorpion: the coup against Chávez and the making of modern Venezuela (online ed.). New York: Nation Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1568584188.

- ^ Kozloff, Nikolas (2007). Hugo Chávez: Oil, Politics, and the Challenge to the U.S. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 45. ISBN 9781403984098.

- ^ Márquez & Sanabria 2018, p. 124

- ^ a b Hellinger, Daniel (2014). Comparative Politics of Latin America: Democracy at Last?. Routledge. ISBN 9781134070077.

- ^ Rivero 2011, p. 118

- ^ "Extradition of Former Venezuelan President Requested". Americas Quarterly. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ BBC, 18 July 2009, Former Venezuela minister charged

- ^ Latin American Herald Tribune, 2 August 2010, Venezuela’s Ex-Defense Chief May Face Charges for ‘89 Repression Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peñaloza, General Carlos (2014). El Delfín de Fidel: La historia oculta tras el golpe del 4F. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 185. ISBN 978-1505750331.

On February 5, 1989, the transmission of Lusinchi's command to Pérez was effected with a lavish ceremony unprecedented in a democracy. Fidel ... was pressured by the "perestroika" that threatened the existence of the Cuban communist regime. The Soviet economic problems made it urgent to control Venezuela to enjoy its oil income ... Fidel stole the show with his Bolivarian allusions of the Latin American Union and a call to fight against Yankee imperialism ... the Cubans and their materials arrived at Caracas on a bus and the buses and trucks to the Eurobuilding hotel ... they were delivered three days before the arrival of Fidel to Cuban G2 officers who paid their rent in advance and made strange demands. ... After the "coronation", part of the Cuban contingent left the country ... sources reported from Maiquetía that fewer Cubans had left than those who had entered

- ^ Prunhuber, Carol (2018). Sangre y asfalto: 135 días en las calles de Venezuela (in Spanish). Kalathos. ISBN 9788494768385.

- ^ Ewell, Judith (March 1989). "Debt and Politics in Venezuela". Current History. 88 (536): 121–124, 147–149. doi:10.1525/curh.1989.88.536.121. S2CID 249702131.

- ^ "Dozens of Venezuelans Killed In Riots Over Price Increases". The New York Times. 1 March 1989.

- ^ López-Maya, Margarita (April 2002). "Venezuela after the Caracazo: Forms of Protest in a Deinstitutionalized context". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 21 (2): 199–218. doi:10.1111/1470-9856.00040. ISSN 0261-3050.

- ^ a b "What was El Caracazo? Part III". Caracas Chronicles. 5 August 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

Bibliography

- López Maya, Margarita (February 2003). "The Venezuelan "Caracazo" of 1989: Popular Protest and Institutional Weakness" (PDF). Journal of Latin American Studies. 35 (1). Cambridge University Press: 117–137. doi:10.1017/S0022216X02006673. S2CID 145292996.

In this regard, the Caracazo was not such a spontaneous outburst as is commonly believed. We have found that anti-neoliberal student protest had been building in the previous days in Merida as well as other cities.

- Márquez, Laureano; Sanabria, Eduardo (2018). "La democracia pierde energía". Historieta de Venezuela: De Macuro a Maduro (1st ed.). Gráficas Pedrazas. ISBN 978-1-7328777-1-9.

- Rivero, Mirtha (2011). La rebelión de los náufragos (9th ed.). Alfa. ISBN 978-980-354-295-5.

- Velasco, Alejandro (2015). "7. Killing Democracy's Promise: A Massacre of People and Expectations". Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520959187. ISBN 978-0-520-95918-7.

Further reading

- "The President's Telephone Conversation with President Carlos Andres Perez of Venezuela on March 3, 1989." George H.W. Bush Presidential Library Archives, Memcons and Telecons. Accessed October 26, 2011.

External links

- Toro, Francisco (7 August 2016). "The Annotated 1989 PROVEA Report". Caracas Chronicles.

- "La sangre & el eco". YouTube. La Vida Bohème. 4 August 2016.

- Riots and civil disorder in Venezuela

- Protests in Venezuela

- 1989 in Venezuela

- 1989 riots

- Carlos Andrés Pérez

- Political repression in Venezuela

- Looting in South America

- February 1989 events in South America

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights cases

- March 1989 events in South America

- 20th-century political riots

- 1980s political events