Gamelan

A gamelan player playing bonang. Gamelan Yogyakarta style during a Javanese wedding. | |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Developed | Indonesia[1] |

| Playing range | |

| Pelog, Slendro, Pathet, Cengkok, Seleh, Sekaran, Imbal, kotekan, Gatra, Colotomy, Gendhing structures, Irama, Gamelan notation | |

| Gamelan | |

|---|---|

Gamelan musical instrument | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Domains | Traditional craftsmanship, oral traditions and expressions, performing arts, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe, social practices, rituals and festive events |

| Reference | 01607 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2021 (16th session) |

| List | Representative List |

Gamelan variations consist of: Javanese gamelan (gamelan jawa) of Central Java and Special Region of Yogyakarta, Balinese gamelan (gamelan bali) of Bali, Sundanese gamelan (gamelan sunda) of West Java, Madurese gamelan (gamelan madura) and Banyuwangian Gamelan (gamelan banyuwangi) of East Java, Gendang beleq of West Nusa Tenggara, Banjarese gamelan (gamelan banjar) of South Kalimantan, Gamelan peking of Lampung, and Talempong of West Sumatra. Gamelan instruments: slab-type (wilahan) instruments (saron/sarun/pemade, demung/sarun ganal, Gendèr/kiliningan, slenthem/selentem/jegogan, peking/sarun paking/kantilan, kecrek/keprak), gong-type (pencon) instruments (gong, kempul, kenong, bonang, trompong, kethuk, talempong, kempyang), String instruments (siter, celempung, kecapi, rebab), Bamboo instrument (suling), Drums instruments (kendhang, Bedug, ketipung, gendang beleq), Wooden instrument (gambang) Idiophone instrument (kemanak) | |

| Gamelan ensemble | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Music of Indonesia (Java, Sunda and Bali ) |

| Cultural origins | Indonesia |

| Typical instruments | |

|

| Music of Indonesia |

| Genres |

|---|

| Specific forms |

|

|

|

|

| Regional music |

Gamelan (/ˈɡæməlæn/[2]) (Template:Lang-jv, Template:Lang-su, Template:Lang-ban) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments.[3][4] The most common instruments used are metallophones (played with mallets) and a set of hand-drums called kendang, which keep the beat. The kemanak, a banana-shaped idiophone, and the gangsa, another metallophone, are also commonly used gamelan instruments on Bali. Other notable instruments include xylophones, bamboo flutes (similar to the Indian bansuri), a bowed string instrument called a rebab (somewhat similar to the gadulka of Bulgaria), and a zither-like instrument called a siter, used in Javanese gamelan. Additionally, vocalists may be featured, being referred to as sindhen for females or gerong for males.[5]

Although the popularity of gamelan has declined slightly since the introduction of modern popular music to Indonesia, the art form is still widely respected, being commonly played in many traditional ceremonies. It may also be performed as entertainment for some modern events, such as official cultural, corporate, government or educational functions, both formal or informal. Gamelan is also, traditionally, arranged and performed to accompany religious rituals, ceremonies, dance theatre, dance-drama, traditional Indonesian theater, wayang puppets theatre, singing, concerts, festivals, exhibitions, and many more. Many consider gamelan to be an integral part of Indonesian culture.[6]

In 2014, Gamelan traditions were recognized as part of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indonesia by the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture.[7]

On December 15, 2021, Gamelan was inscribed onto the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The nomination builds on the archaeological connection to the Borobudur, and includes a focus on its role in fostering a sense of national identity and pride, in addition to wellbeing aspects such as mental health, the development of interpersonal skills and the connection between its cosmology and an ethics of mutual respect and care. The listing consists of Javanese gamelan (gamelan jawa) of Central Java and Special Region of Yogyakarta, Balinese gamelan (gamelan bali) of Bali, Sundanese gamelan (gamelan sunda) of West Java, Madurese gamelan (gamelan madura) and Banyuwangian Gamelan (gamelan banyuwangi) of East Java, Gendang beleq of West Nusa Tenggara, Banjarese gamelan (gamelan banjar) of South Kalimantan, Gamelan peking of Lampung, and Talempong of West Sumatra as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity from Indonesia, and encouraged the Indonesian people and the Indonesian government to safeguard, transmit, promote, and develop the gamelan.[8] Methods include the support of national, international and provincial festivals, the establishment of educational curricula including the Gamelan Goes to School program, an intention to increase the numbers of regional gamelan associations, and cultural diplomacy by sending gamelan specialists to global universities.

Etymology

The word gamelan comes from the Javanese word gamel (ꦒꦩꦼꦭ꧀), which refers to playing of percussion instruments or the act of striking with a mallet, and the noun-forming suffix an.[9][5][10] The gamelan in the Sundanese is Degung (Degung), the word Degung apparently is an old Sundanese term, which refers to gongs and Gong ensembles. For this reason, the words degung and gong are essentially synonyms for the word gamelan. At the same time, the expression gamelan degung may be a way to point at a gamelan ensemble tuned to degung scale.[11] The term karawitan (ꦏꦫꦮꦶꦠꦤ꧀) refers to classical gamelan music and performance practice, and comes from the Javanese word rawit (ꦫꦮꦶꦠ꧀) of Sanskrit origin, meaning 'intricate' or 'finely worked',[10] referring to the sense of smoothness and elegance idealized in Javanese music. Another word, pangrawit (ꦥꦁꦫꦮꦶꦠ꧀), means a person with such sense, and is used as an honorific when discussing esteemed gamelan musicians. The high Javanese word for gamelan is gangsa (ꦒꦁꦱ), formed either from the words tembaga (ꦠꦼꦩ꧀ꦧꦒ) and rejasa (ꦉꦗꦱ) referring to the materials used in bronze gamelan construction (copper and tin), or tiga (ꦠꦶꦒ) and sedasa (ꦱꦼꦢꦱ) referring to their proportions (three and ten).[12]

History

The gamelan predates the Hindu-Buddhist culture that dominated Indonesia in its earliest records and thus represents an indigenous art form of Indonesia. In contrast to the heavy Indian influence in other art forms, the only obvious Indian influence in gamelan music is in the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese style of singing, and in the themes of the Wayang kulit and Wayang Golek (shadow puppet plays).[13]

In Javanese mythology, the gamelan was created by Sang Hyang Guru in Saka era 167 (c. AD 230), the god who ruled as king of all Java from a palace on the Maendra mountain in Medang Kamulan (now Mount Lawu). He needed a signal to summon the gods and thus invented the gong. For more complex messages, he invented two other gongs, thus forming the original gamelan set.[14]

The earliest image of a musical ensemble is found on the bas-relief of the 8th century Buddhist monument of Borobudur, Central Java.[1] The Borobudur's musicians play lute-like stringed instruments, various of kendang drums, various of suling flutes, cymbals, bells, metallophones, and xylophones. Some of these musical instruments are indeed included in a complete gamelan orchestra. Musical instruments such as metallophones (saron, kenong, kecer), xylophones (gambang), the bamboo flute (suling), drums in various sizes (kendang), cymbals, bell (genta), lute, and bowed and plucked string instruments were identified in this image.[15] These reliefs of this musical ensemble are suggested to be the ancient form of the gamelan.

The instruments developed into their current form during the Majapahit Empire. According to the inscriptions and manuscripts (Nagarakretagama and Kakawin Sutasoma) dated from the Majapahit period, the kingdom even had a government office in charge of supervising the performing arts, including the gamelan. The arts office oversaw the construction of musical instruments, as well as scheduling performances at the court.[1]

In Bali, there are several gamelan selonding that have existed since the 9th century during the Sri Kesari Warmadewa reign.[16][17] Some words refer to gamelan selonding was found in some ancient Balinese inscriptions and manuscripts. Today, gamelan selonding is stored and preserved well in ancient temples of Bali. It is considered sacred and used for religious ceremony purposes, especially when the big ceremony is held. Gamelan Selonding is part of daily life and culture for some indigenous people in ancient villages such as Bungaya, Bugbug, Seraya, Tenganan Pegringsingan, Timbrah, Asak, Ngis, Bebandem, Besakih, and Selat in Karangasem Regency.

In the court of Java (Surakarta Sunanate and Yogyakarta Sultanate) the oldest known ensembles, Gamelan Munggang and Gamelan Kodok Ngorek, are apparently from the 12th century.[18] These formed the basis of a "loud style" of music. These Gamelan are the oldest existing gamelan instruments and still preserved well in the courts. The Gamelans become the heirloom of the Javanese courts. Gamelan Kodhok Ngorek and Gamelan Monggang are sacred gamelan that will only be sounded for Javanese court ritual ceremonies such as the Sultan's Jumenengan (coronation ceremony), welcoming highly respected guests at the palace, royal weddings, and Garebeg.[19] This gamelan is only owned by the court and the general public is not allowed to have a similar gamelan set.

In the wengker or Ponorogo culture, in the 15th century Gamelan Reyog was not only used to accompany the art of Reog Ponorogo but was also used during war, the troops of ki Ageng Surya Alam from the village of Kutu played gamelan reyog before the war took place against Majapahit, which was in coalition with Demak during the attack. Wengker, as a result Wengker always gets his victory before the heirloom of ki Ageng Surya Alam falls into the hands of the enemy.[20]

A "soft style" developed out of the kemanak tradition and is related to the traditions of singing Javanese poetry, in a manner often believed to be similar to the chorus that accompanies the modern bedhaya dance. In the 17th century, these loud and soft styles mixed, and to a large extent, the variety of modern gamelan styles of Bali, Java, and Sunda resulted from different ways of mixing these elements. Thus, despite the seeming diversity of styles, many of the same theoretical concepts, instruments, and techniques are shared between the styles.[21]

In the Sultanate of Cirebon, on the north coast of Java. The gamelan Sakati in the Keraton Kasepuhan is originated from Demak Sultanate in 1495 which was a gift from Sultan Trenggono of Demak for the marriage of Ratu Mas Nyawa (daughter of Raden Patah, king of Demak) to Prince Bratakelana (son of Sunan Gunung Jati from his wife Syarifah Bagdad).[22] This gamelan is closely related to the early days of the spread of Islam by Wali Sanga in Java. At the Keraton Kasepuhan, the gamelan Sakati is played on the Idul Adha month of Hajj (Zulhijah) in the Sri Manganti building when the sultan and his relatives head to the Grand Mosque. This gamelan is kept in the Museum Pusaka Keraton Kasepuhan Cirebon.[23]

In Lamongan, East Java, there is an ancient gamelan from the 15th century called Gamelan Singo Mengkok. This gamelan is a legacy of the Sunan Drajat (one of the Wali Sanga) which was used for broadcasting the Islamic religion in Paciran, Lamongan. Beaten by the Friends of Sunan Drajat to accompany the tembang Pangkur (panguri isine Qur'an) created by Sunan Drajat himself. This gamelan ensemble is an acculturation of Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic culture, considering that the surrounding community is Hindus, so that it is easily accepted by the community. The Gamelan Singo Mengkok is now stored in the Museum Sunan Drajat in Lamongan.[24]

In the kingdom of Islamic Mataram, Gamelan Kanjeng Kyai Guntur Sari was made in 1566[25] and Gamelan Kanjeng Kyai Guntur Madu was made in 1642 during the reign of Sultan Agung.[26] Both gamelans called Gamelan Sekati (Gamelan Sekaten) which is only beaten/sounded to accompany the Sekaten ceremony. Gamelan Sekaten in Surakarta and Yogyakarta will be played once a year for one week in front of the Grand Mosque. This gamelan is only played by the royal family and courtiers under strict conditions, wearing prescribed traditional clothes, and playing certain sacred music that has existed for centuries. The Gamelan Sekaten exists in halves: divided between the two rival courts in Surakarta and Yogyakarta, each court had a matching second half made.

In Sumedang, West Java, there is an heirloom of the Kingdom of Sumedang Larang, there is a Gamelan Panglipur belonging to Prince Rangga Gede / Kusumahdinata IV (1625–1633) who is also the regent of Mataram.[27] Gamelan was deliberately made to entertain himself after his beloved child died. The Panglipur gamelan along with 9 other ancient gamelan sets are kept at the Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun in Sumedang Regency.[28] One of the ten sets of gamelan is the gamelan Sari Oneng Parakansalak from Sukabumi, West Java, which on 31 March 1889, participated in celebrating the inauguration of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France.[29][30]

On 5 September 1977, Gending ketawang puspawarna (Javanese gamelan music) which was created by Mangkunegara IV (1853–1881) was carried by two satellites of The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) named Voyager I and Voyager II. The satellites are in charge of making observations on planets in outer space. The two satellites are equipped with gold-plated copper disks with a diameter of 12 inches. This disc contains recorded messages from Earth for extraterrestrials who can find them.[31][32]

Instruments

A gamelan is a multi-timbre ensemble consisting of metallophones, xylophones, flutes, gongs, voices, as well as bowed and plucked strings. The hand-played drum called kendang controls the tempo and rhythm of pieces as well as transitions from one section to another, while one instrument gives melodic cues to indicate treatment or sections of a piece.

Typical Javanese gamelan instruments

In the courts of Java, Javanese gamelan is grouped into 2 groups of gamelan, namely gamelan Pakurmatan and gamelan Ageng. Gamelan pakurmatan is the gamelan used for special Javanese court events and all of them are sacred gamelan. The gamelan pakurmatan consists of the gamelan kodhok ngorek, the gamelan monggang, the gamelan sekati, and the gamelan carabalen. As for the gamelan ageng is considered the most complete in the Javanese court. The Gamelan Ageng instruments are usually owned by the general public (artists, schools, studios, and other communities) in Java and outside Java. This gamelan is used to accompany arts or rituals either in the palace or in the general public, the gamelan can use a complete gamelan or less.

A set of complete Javanese Gamelan Ageng Ensemble maintained by the Javanese court consists of:

- 2 Sets Bonang Penembung

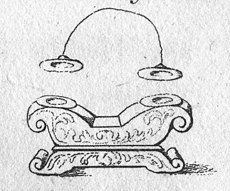

- 2 Sets Bonang Barung (Bonang)

- 2 Sets Bonang Penerus

- 2 Sets Kenong

- 2 Pieces Kethuk

- 2 Pieces Kempyang

- 2 Sets Slenthem

- 3 Sets Gendèr Barung (Gendèr)

- 3 Sets Gendèr Penerus

- 2 Sets Saron Demung (Demung)

- 4 Sets Saron Barung (Saron/Saron Ricik)

- 2 Sets Saron Peking (Peking/Saron Penerus)

- 2 Pieces Gong Ageng (Gong Besar)

- 2 Pieces Gong Suwukan (Gong Siyem)

- 2 Sets Kempul

- 1 Piece Kendang Ageng (Kendhang Gending)

- 1 Piece Kendang Ciblon (Batangan)

- 1 Piece Kendang Sabet (Kendhang Wayangan)

- 1 Piece Kendang Ketipung (Ketipung)

- 1 Piece Bedug

- 2 Pieces Rebab

- 2 Sets Gambang

- 2 Pieces Siter

- 2 Pieces Celempung

- 2 Pieces Suling (Seruling)

- 1 Piece Kecer

- 3 Pieces Kepyak

- Sindhen – Female singer in a gamelan

- Gerong – Male singer in a gamelan

- Nayaga (Wiyaga) – Gamelan musicians

- Typical Javanese Gamelan Instruments

-

Suling or Seruling

Typical Balinese gamelan instruments

In Bali, the Gamelan instruments are all kept together in a balé, a large open space with a roof over the top of it and several open sides. Gambelan (the Balinese term) are owned by a banjar, nobility or temples and kept in their respective compounds. In case of banjar ownership the instruments are all kept there together because people believe that all the instruments belong to the community as a whole and that no one person has ownership over an instrument. Not only is this where the instruments are stored, but this is also the practice space for the sekaha (Gamelan orchestra group). The open walls allow for the music to flow out into the community where the rest of the people may enjoy it. Balinese gamelan cannot be heard inside closed rooms, because it easily crosses the threshold of pain. This does not apply to small ensembles like a gamelan gendér.

The sekaha is led by a single instructor whose job it is in the community to lead this group and to come up with new pieces. When they are working on a new piece, the instructor will lead the group in practice and help the group form the new music as they are practicing. When the instructor creates a new song, he leaves enough open for interpretation that the group can improvise, so the group will write the music as they practice it. There are many styles in Balinese gamelan. Kebyar is one of the most recent ones. Some Balinese gamelan groups constantly change their music by taking older pieces they know and mixing them together, as well as trying new variations of the music. Their music constantly changes because they believe that music should grow and change; the only exception to this is with their most sacred songs which they do not change. A single new piece of music can take several months before it is completed. Men and women usually perform in separate groups.

A set of complete Balinese gamelan ensemble consists of:

- 1 set (12 pieces) Reyong

- 1 set (10 pieces) Trompong

- 1 piece Gong Wadon

- 1 piece Gong Lanang

- 1 piece Gong Kempur

- 1 piece Gong Klentong

- 1 piece Gong Bende

- 1 Set Kenong (Kajar)

- 1 piece Kethuk (Kempli)

- 2 sets Jiyèng (Ugal)

- 4 sets Gangsa (Pemande)

- 4 sets Kanthilan

- 2 sets Jublag

- 2 sets Jegogan

- 2 sets Penyacah Kenyur

- 2 sets Gendèr Rambat

- 1 set Cèng-cèng Ricik

- 8 sets Cèng-cèng Kepyak

- 2 pieces Kendang Semaradana (Cedugan)

- 2 pieces Kendang Batel (Krumpung)

- 1 set Gentorak

- 3 pieces Suling

- Nayaga (Wiyaga) – Gamelan musicians

- Typical Balinese gamelan instruments

-

Gong Lanang

-

Gong Wadon

-

Gong Klentong

-

Trompong

-

Reyong

-

Ugal

-

Kantilan

-

Pemade

-

Kenyur

-

Jegogan

-

Jublag

-

Klenang

-

Kendang Semaradana

-

Ceng-ceng Kepyak

-

Ceng-ceng Ricik

-

Gentora

-

Suling gambuh

-

Gender wayang

-

Rindhik

-

Curing

Notation

The tuning and construction of a gamelan orchestra is a complex process.[33] Javanese gamelan use two tuning systems: sléndro and pélog. There are other tuning systems such as degung (exclusive to Sunda, or West Java, similar with Japanese ryukyuan scale), and madenda (similar to a Japanese hirajoshi scale). In central Javanese gamelan, sléndro is a system with five notes to the octave, with large intervals, while pélog has seven notes to the octave, with uneven intervals, usually played in five note subsets of the seven-tone collection. A full gamelan will include a set of instruments in each tuning, and classically only one tuning is used at a time. The precise tuning used differs from ensemble to ensemble and gives each ensemble its own particular flavor. A set of gamelan instruments will be tuned to the same set of notes, but the tuning will vary from one gamelan to the next, including variations in the size of intervals.

Colin McPhee, a Canadian composer who spent much time in Bali, remarked, "Deviations in what is considered the same scale are so large that one might with reason state that there are as many scales as there are gamelans."[34] This view is contested, however, by some teachers of gamelan, and there have been efforts to combine multiple ensembles and tuning structures into one gamelan to ease transportation at festival time. One such ensemble is gamelan Manikasanti, which can play the repertoire of many different ensembles.

Balinese gamelan instruments are built in pairs that are tuned slightly apart to produce interference beats, ideally at a consistent speed for all pairs of notes in all registers. This concept is referred to as "ombak," translating to "wave," communicating the idea of cyclical undulation. One instrument, tuned slightly higher, is thought of as the "inhale," and the other, slightly lower, is called the "exhale" (Also called the "blower" and the "sucker," or pengimbang and pengisep in Bali). When the inhale and the exhale are combined, beating is produced, meant to represent the beating of the heart, or the symbol of being alive. It is thought that this contributes to the "shimmering" sound of Balinese gamelan ensembles. In the religious ceremonies that contain gamelan, these interference beats are meant to give the listener a feeling of a god's presence or a stepping stone to a meditative state. The scale roughly approximates that of the phrygian mode of the Western major scale (E-E on the white keys of the piano), with the notes EFGBC corresponding to the note positions 12356 in the slendro scale used by most gamelan.[35]

In addition to non-western scales, Javanese gamelan uses a combination of tempo and density known as Irama, relating how many beats on the saron panerus instrument there are to notes in the core melody or balungan; density is considered primary.[36]

Slendro

Slendro notation generally produces a light, cheerful atmosphere and feels busier. This is evidenced by the scenes in the wayang kulit and wayang wong performances such as scenes of war and marching that accompanied by slendro notation. The use of the slendro can also have the opposite impression, such as sad or romantic. As in the case of gending that uses a slendro miring. Slendro miring is a slendro notation tone that is played out of place on purpose. Therefore, there are many scenes of homesickness, love missing, sadness, death, languishing accompanied by slendro tunes.

Pelog

Pelog notation produces an atmosphere that gives the impression of being manly, regal, and sacred, especially in the musical play that uses the pelog nem (six) notation. Therefore, there are many scenes that are accompanied by pelog tunings, such as scenes where a king enters the pamelegan (place of worship), scenes of heartache, scenes of anger, or scenes that express revenge. However, in the play of certain notes, the pelog tunings can also give the impression of being happy, light, and lively, for example in the music played on the pelog tunings of barang.

Kepatihan

Gamelan music is traditionally not notated and began as an oral tradition. In the 19th century, however, the kraton (palaces) of Yogyakarta and Surakarta developed distinct notations for transcribing the repertoire. These were not used to read the music, which was memorized, but to preserve pieces in the court records. The Yogyanese notation is a checkerboard notation, which uses six or seven vertical lines to represent notes of higher pitch in the balungan (melodic framework), and horizontal lines which represent the series of beats, read downward with time. The fourth vertical line and every fourth horizontal line (completing a gatra) are darkened for legibility. Symbols on the left indicate the colotomic or metric structure of gongs and so forth, while specific drum features are notated in symbols to the right. The Solonese notation reads horizontally, like Western notation, but does not use barlines. Instead, note values and rests are squiggled between the notes.[37]

Today this notation is relatively rare, and has been replaced by kepatihan notation, which is based on the Galin-Paris-Chevé system. Kepatihan notation developed around 1900 at the kepatihan Palace in Surakarta, which had become a high-school conservatory. The pitches are numbered (see the articles on the scales slendro and pélog for an explanation of how), and are read across with dots below or above the numbers indicating the register, and lines above notes showing time values; In vocal notation, there are also brackets under groups of notes to indicate melisma. Like the palace notation, however, Kepatihan records mostly the balungan part and its metric phrases as marked by a variety of gongs. The other parts are created in real time, and depend on the knowledge each musician has of his instrument, and his awareness of what others are playing; this "realization" is sometimes called "garap." Some teachers have also devised certain notations, generally using kepatihan principles, for the cengkok (melodic patterns) of the elaborating instruments. Some ethnomusicologists, trained in European music, may make transcriptions onto a Western staff. This entails particular challenges of tuning and time, sometimes resulting in unusual clefs.[38]

Varieties

Varieties of gamelan are distinguished by their collection of instruments and use of voice, tunings, repertoire, style, and cultural context. In general, no two gamelan ensembles are the same, and those that arose in prestigious courts are often considered to have their own style and tuning. Certain styles may also be shared by nearby ensembles, leading to a regional style. The varieties are generally grouped geographically, with the principal division between the styles favored by the Balinese, Javanese, and Sundanese peoples. Javanese gamelan has soft and slow tones, while Balinese gamelan has strong and dynamic tones with fast music rhythms, while Sundanese gamelan which is dominated by the sound of flutes makes it not only soft but also mellow.[39]

Javanese gamelan

Javanese gamelan is a gamelan that originates and develops in the Central Java and East Java, including the Special Region of Yogyakarta. In the Javanese palaces, the gamelan is divided into two, namely the gamelan pakurmatan and gamelan ageng. Gamelan pakurmatan is used for certain events or rituals in the royal environment. The gamelan pakurmatan set is not as complete as the ageng gamelan, and its shape and pitch are somewhat different from the traditional gamelan owned by the community. Gamelan pakurmatan consists of gamelan kodhok Ngorek, gamelan munggang, gamelan sekati, and gamelan carabalen, while gamelan ageng is the most complete gamelan used for various traditional ceremonies and events in the palace.[40]

Gamelan outside the palace, owned by the general public, is usually the gamelan ageng, although it is not as complete as that of the palace, according to the needs and objectives of the gamelan ownership. The Javanese gamelan used by the communities has many kinds and types including the gamelan gadhon, gamelan siteran, gamelan Wayang, gamelan bambu, gamelan prawa, gamelan pelog, gamelan renteng, gamelan slendro, gamelan Banyuwangi, and gamelan Madura.

In oral Javanese culture distinctions are made between complete or incomplete, archaic and modern, and large standard and small village gamelan. The various archaic ensembles are distinguished by their unique combinations of instruments and possession of obsolete instruments such as the bell-tree (byong) in the 3-toned gamelan kodhok ngorek. Regionally variable village gamelan are often distinguished from standard gamelan (which have the rebab as the main melodic instrument) by their inclusion of a double-reed wind (selompret, slompret, or sompret) in addition to variable drum and gong components, with some also including the shaken bamboo angklung.[41]

Gamelan in Javanese society is a product of local wisdom that has survived to this day. The long history that has been passed by Javanese gamelan is a cultural struggle that continues to be sustainable until now and in the future.[42] Gamelan is inseparable from Javanese customs and human life, where gamelan is almost always there in every Javanese ceremony are held. Javanese gamelan is generally used to accompany dances, dance dramas, theater, puppets, rituals, events and festivals. Until then it developed in such a way that it was able to stand as a separate musical performance, complete with the accompaniment of the voices of the sindhen.[43]

Most of the music rhythms are generally soft and reflect the harmony of life, as the principles of life are generally adopted by Javanese society. Some of them sound quickly according to the event or ritual being held or accompanied by the gamelan like gamelan Banyuwangi which has a faster tempo and uses high notes. Javanese gamelan has pelog and slendro tunings, if the pelog consists of notations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (ji, ro, lu, pat, mo, nem, tu), slendro has notation 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, i (ji, ro, lu, mo, nem, i).

- Javanese gamelan

-

Javanese gamelan being played in Keraton Yogyakarta, Indonesia, on 25 October 2009

-

Wayang Kulit performance with Gamelan accompaniment in the context of the appointment of the throne for Hamengkubuwono VIII's fifteen years in Yogyakarta, between 1900 and 1940

-

A gamelan ensemble with a group of singers (Sindhen (Female) and Gerong (Male) at the Mangkunegaran Royal Palace in Surakarta, Central Java, between 1870 and 1892

-

A Gamelan Ensemble was played to accompany the inauguration of the Prince of the late Paku Alam VII at Pakualaman Palace, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, before 1949

-

A Dalang (puppeteer), Sindhen (singer) and Wiyaga (gamelan musicians) with a Javanese gamelan at Keraton Yogyakarta, the sultan's palace in Yogyakarta c. 1885

-

Gamelan orchestra in East Java, late 19th century

Balinese gamelan

Balinese gamelan is one type of traditional gamelan ensemble that originates and develops in the island of Bali. Balinese gamelan is an inseparable ensemble of Balinese life, almost all villages in Bali have gamelan. The gamelan can be used as part of Hindu worship in Bali or as community entertainment in the Banjar in villages of Bali. Because gamelan also functions as a medium for socializing with each other, it can be seen that playing gamelan requires cooperation between players to get the desired tone or sound harmony. This Balinese gamelan has several differences from gamelan instruments in general, both in form and how to play it. This Balinese gamelan is usually performed as an accompaniment to an art performance in Bali, both sacred and entertainment.

Balinese gamelan is often used to accompany religious ceremonies and entertainment. In terms of religion, Balinese Gamelan is often displayed to accompany the running of religious ceremonies or to accompany sacred traditional dances. Meanwhile, in terms of entertainment, Balinese Gamelan is often presented as a musical performance as well as accompaniment to various arts that are entertainment in Bali.

Gamelan in Bali known as gambelan is commonly used in traditional ritual processions such as death ceremonies which we know as the Ngaben tradition. Meanwhile, for human ceremonies, gender is used and for ceremonies in temples, gong gede is usually used. In terms of the development of the era, Balinese gamelan can be divided into 3 types:[44]

- Gamelan wayah. This old type of gamelan is thought to have existed before the 15th century. This gamelan is generally dominated by keys in the form of keys and does not use drums (Selonding, Gender Wayang, Baleganjur, Genggong, Gambang, Angklung, Bebonangan, Geng Beri, Caruk, Gong Luwang)

- Gamelan madya. This gamelan comes from around the 16th-19th century. In this era, the barungan gamelan already used drums and tuned instruments. In this barungan, drums have started to play a role in a show (Bebarongan, Pelegongan, Batel Barong, Joged Pingitan, Penggambuhan, Gong Gedé, Semar Pagulingan)

- Gamelan anyar. This gamelan includes a new type of group, which includes the types of gamelan barungan that emerged in the 20th century. This gamelan barungan appears in one of the most prominent features, namely the game of drums (Semaradana, Bumbung Gebyog, Adi Merdangga, Jégog, Manikasanti, Bumbang, Gong Suling, Joged Bumbung, Janger, Geguntangan, Genta Pinara Pitu, Kendang Mabarung, Gong Kebyar, Okakan or Grumbungan, Tektekan)

- Balinese Gamelan

-

A balinese dancer performed Kebyar duduk dance accompanied by a Balinese gamelan Ensemble, Bali, Indonesia, before 1952

-

Balinese girls practiced legong dance accompanied by gamelan in Ubud, Bali, Dutch east Indies, between 1910 and 1930

Sundanese gamelan

The Sundanese gamelan is one of the typical gamelan ensemble from West Java and Banten province (Tatar Pasundan ) in Indonesia. In the manuscript Sanghyang Siksa Kandang Karesian, the art of gamelan is estimated to have entered in the 16th century. In this text, at that time there was a gamelan player called Kumbang Gending and a musical expert called Paraguna. Sundanese gamelan is also called Degung. The word Degung is said to have originated from the word "Ratu-agung" or "Tumenggung", because at that time Gamelan Degung was very popular with the officials. There are three types of Sundanese gamelan, including:

- Gamelan salendro is usually used to accompany wayang performances, dances, and cliningan. Because it is often used in the performing arts, the salendro gamelan is also a popular gamelan among other gamelan types.

- Gamelan renteng. This gamelan developed in several places, one of which is in Batu Karut, Cikalong. Based on the form and intervals of the gamelan renteng, there is an opinion that most likely the current Sundanese gamelan started from the gamelan renteng.

- Gamelan ketuk tilu. This gamelan is usually used to accompany the arts of ketuk tilu, ronggeng gunung, ronggeng ketuk, doger, and topeng banjet.

- Sundanese Gamelan

-

Sundanese Gamelan with a dancer and Wayang Golek in a hut in Cibodas Botanical Garden, West Java on 28 September 1904

-

A gamelan ensemble and Dance show party for the regent of Preanger (Now Parahyangan) West Java, between 1880 and 1920

-

Sundanese gamelan ensemble of Bandung's Regent, West Java, Dutch east Indies, between 1857 and 1890

-

A gamelan laras slendro Si Ketuyung (sacred gamelan), a set of gamelan instruments made in 1748, a legacy of Sultan Sepuh IV, Keraton Kasepuhan, Cirebon, Indonesia

Outside the main core on Java and Bali, gamelan has spread through migration and cultural interest, new styles sometimes resulting as well. The variety of gamelan can be found in over 25 countries outside Indonesia, presenting both traditional and experimental repertoire.

Cultural context

For some Indonesians, gamelan has high philosophical values, in terms of sound, roles, and the feelings of the players. Playing gamelan is not just the ability to play various musical instruments together, thus giving birth to the harmony of tones and rhythms. But also, by playing the gamelan there is a meaning that describes the system of deliberation and consensus in the midst of society, through each gamelan musical instrument. Gamelan symbolizes the spirit of cohesiveness and mutual cooperation, together, and in line. So that it gives birth to a harmonious tone in social life. In Indonesia, gamelan accompanies many cultural activities such as:

Religious rituals

Under the influence of the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit kingdom, gamelan was used as accompaniment in religious ceremonies with tembang (singing) and wayang performances. Even an accompaniment to a king's performance. In the Negarakertagama manuscripts written by Mpu Prapanca in the 14th century. It is said that the gamelan accompaniment was used by King Hayam Wuruk in performing a mask dance with eight young people accompanied by a song from the Queen Mother. With the collapse of the Majapahit kingdom and being replaced by the Islamic kingdom of Demak led by Raden Patah, gamelan as a traditional musical instrument did not just disappear. Its function is used as a media tool for preaching Islam.

Gamelan's role in rituals is so important that there is a Javanese saying, "It is not official until the gong is hung".[45] Some performances are associated with royalty, such as visits by the sultan of Yogyakarta. Certain gamelans are associated with specific rituals, such as the Gamelan Sekaten, which is used in the celebration of Mawlid an-Nabi (Muhammad's birthday). In Bali, almost all religious rituals include gamelan performance. Gamelan is also used in the ceremonies of the Catholic church in Indonesia.[46] Certain pieces are designated for starting and ending performances or ceremonies. When an "ending" piece (such as "Udan Mas") is begun, the audience will know that the event is nearly finished and will begin to leave. Certain pieces are also believed to possess magic powers and can be used to ward off evil spirits.[45] The religious rituals that accompanied by gamelan such as: sekaten,[47] temple rituals, melasti, galungan, Ogoh-ogoh, etc.

- Some religious rituals in Indonesia that use gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Sekaten, Gamelan Sekaten Kanjeng Kiai Guntur Madu (One of Some Javanese Sacred Gamelan) is usually beaten every day for a week during the Sekaten celebration at the Keraton Yogyakarta. The community was very enthusiastic about listening to the strains of the heirloom gamelan, on 26 November 2017

-

Galungan, a Balinese holiday celebrating the victory of dharma over adharma in Besakih temple complex in Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia

-

Odalan or piodalan is temple anniversary in Bali, held usually once every 210 days, a complete cycle according to Balinese calendar.

Ceremonies

Gamelan is used to accompany various traditional ceremonies in Indonesia, gamelan kodhok ngorek, gamelan monggang, gamelan carabalen, and gamelan ageng are used for important ceremonies related to kings in the Yogyakarta and Surakarta palaces such as the king's coronations ceremony, the king's birthday ceremony, the coronation anniversary, royal guest reception, baby birth, marriage, death, and so on. Outside the palace in Java, gamelan is used for Wedding reception, birth ceremonies, circumcision ceremonies, rice harvesting, ruwatan ceremonies, and death ceremonies (dhukitan). The musical presentation in the dhukitan ceremony in the general public is different from that in Palace. Gendhing at dhukitan ceremonies in the palace use the kodhok ngorek gamelan instrument, only intended for the death of the king and his family and only served when the corpse departs to the cemetery. Meanwhile, gendhing offerings at duhkitan ceremonies in the general public (outside the palace environment) are usually served at the time of the death of musical artists of dance, musical puppetry, wayang orang, cultural observers, and theater using the gamelan gadhon ensemble.

- Some Indonesian traditional ceremonies that use gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Tingalan Dalem Jumenengan, The 40th Royal coronations anniversary of Susoehoenan Pakubuwono X in Surakarta Sunanate.

Traditional dances

Almost all dances originating from the island of Java and Bali are accompanied by gamelan music. Gamelan gives spirit and beauty to live dance performances. The sound of the gamelan music brings dance to life and graceful to see. The main function of the gamelan as a dance accompaniment is to provide rhythm, beat, or tempo guidance. So that the selection of accompanying music must be adjusted to the rhythm and theme of the dance. Dance performance using live gamelan is a complex artistic activity. Gamelan in dance is used as an illustration or support for the atmosphere. The accompanying gamelan music must give the impression of "speaking" or communication and constitute the perfect unity between music and dance. Typically players in the gamelan will be familiar with dance moves and poetry, while dancers are able to play in the ensemble.[48] Some examples of famous dance include: bedhaya, serimpi, gambyong, Bambangan Cakil, legong, oleg tamulilingan, pendet, cendrawasih, barong, baris, jaipong, topeng, Bajidor Kahot, gandrung, etc.

- Some Indonesian Traditional dance that use Gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Legong, Legong Kraton Dance (Legong of the Palace) in Ubud Palace, Bali, Indonesia. In the background, the Gamelan orchestra accompanies the performance, on 23 August 2008

Dance-drama performances

Dance drama in Indonesia is a show that combines dance and drama, which tells a story with dialogue or without dialogue between the players, usually guided by a puppeteer. This show is accompanied by gamelan music and involves many players who wear a typical costume. Gamelan music as accompaniment is widely used for choreography in the form of storytelling performances, both drama, and dance drama. Gamelan music that accompanies dance drama is a combination of music whose rhythm is in accordance with the dance movements and as an illustration. Most dance-dramas use music to avoid monotony and be more varied, and for the sake of harmony between dance and music. Ramayana Ballet is a form of Javanese dance-drama performance that does not use dialogue. Dialogue in ballet performances is replaced with gesticulation or meaningful movements, especially with attitudes, hand movements, and head. Gesticulation or meaningful movements are movements that have a visual meaning or purpose that can be used and implemented by the audiences. Some examples of dance-dramas in Indonesia are as follows: wayang wong, wayang topeng, Ramayana Ballet, etc.

- Some Dance drama performances that use gamelan as an accompaniment

-

King Duryodana in Wayang wong performance in Taman Budaya Rahmat Saleh, Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia

Wayang puppet performances

Gamelan is used to accompany all puppet shows, including wayang kulit, wayang golek, wayang klithik, wayang beber, etc. In wayang, the dalang (puppeteer) must have a thorough knowledge of gamelan, as he gives the cues for the music. Gamelan is a complement and supporter of wayang performances, which is still favored by Indonesians. Gamelan is played to support the atmosphere that Dalang (puppet master) wants to build in a wayang performance. Gamelan, which is the music accompanying the puppet show, is played in pelog or slendro tones according to the atmosphere of the scene being played. Gamelan music supports the delivery of values in wayang performances. The type of gamelan music for puppetry is different from gamelan music for dance or ordinary musical songs.

- Some Wayang Puppet Show that use Gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Dalang (Puppet master), Sindhen (traditional Javanese singer), and Wiyaga (Gamelan musicians) in Wayang Kulit Show in Java

-

Wayang Golek Performance in Yogyakarta

-

Wayang Beber performance of the desa Gelaran at the home of Dr. Wahidin Soedirohoesodo at Yogyakarta in the middle Dr. GAJ Hazeu, Dutch East Indies, in 1902

Traditional theatre performances

Traditional theater, especially on the islands of Java and Bali, is mostly accompanied by gamelan. Traditional theaters such as kethoprak, ludruk, and sandiwara are accompanied by gamelan to enliven the show. Ketoprak is a traditional theater founded in central Java. The story is usually about the life of Javanese palaces and noblemen, often about the romance of the royal family members. Ketoprak is often performed in celebrations, such as weddings, circumcision, and Independence Day. It differs from Ludruk from east Java, which uses a contemporary setting and the story of common people and their economic struggles. All the performers of ludruk are males, even the female role is played by males. While Sandiwara is a traditional theatrical drama from west Java.

- Some traditional theatre performance that use gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Kethoprak (Javanese popular drama depicting legends, historical or pseudo-historical events). Performance by Kethoprak Tobong Kelana Bhakti Budaya, Bantul, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Singing performance

Gamelan can be performed by itself – in "klenengan" style, or for radio broadcasts – and concerts presentation are common in national arts conservatories founded in the middle of the 20th century.[49] Gamelan is frequently played on the radio. For example, the Pura Pakualaman gamelan performs live on the radio every Minggu Pon (a day in the 35-day cycle of the Javanese calendar).[45] In major towns, the Radio Republik Indonesia employs professional musicians and actors, and broadcast programs of a wide variety of gamelan music and drama.[50] In the court tradition of central Java, gamelan is often played in the pendopo, an open pavilion with a cavernous, double-pitched roof, no side walls, and a hard marble or tile floor. The instruments are placed on a platform to one side, which allows the sound to reverberate in the roof space and enhances the acoustics.[51] Some traditional genre music is accompanied by gamelan ensemble like Javanese poetry, tembang sunda, campursari, etc.

- Some Traditional singing performance that use gamelan as an accompaniment

-

Javanese poetry, Sindhens performance with a gamelan ensemble on a ceremony in Java, Indonesia, on 5 November 2015

-

tembang sunda, Sundanase singer sings Sundanese song in a festival

-

Campursari performance by Didi kempot

Festival

Many festivals are held in Indonesia, most of them using gamelan to enliven the event. Usually, gamelan is used for entertainment performances or even gamelan becomes the theme of the festival. Several gamelan festivals in Indonesia are held regularly, such as the Gamelan festival in Solo, Yogyakarta International gamelan festival, Balinese art festival, and many more.

- Some Festivals in Indonesia

-

Balinese women gamelan Gong Kebyar in Balinese Cultural Festival, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia, on 17 June 2013

-

Gamelan performance at Borobudur International Performances and Art Festival 2018

-

Gamelan players at Balinese art festival 2018

Gamelan production

Most of the metal gamelan instruments are made of bronze or brass or iron, while some are made of wood, bamboo, leather, and strings. Gangsa is short for Tigang (three) and Sedasa (ten), the term for gamelan in the high Javanese language based on the composition of the ingredients for making the best gamelan (bronze), namely ten parts copper and three parts tin. Pande is the name for a gamelan maker, while Pelaras is a person who adjusts the gamelan tone to match the existing gamelan standards. In the process of making gamelan, there are at least five stages that must be passed to make a good gamelan. The five stages include:

Membesot – to melt the mixture, a gamelan craftsman will prepare the kowi, which is a bowl-like container made of clay. In this process, a fireplace equipped with a heating device is prepared to produce maximum heat. The kowi is then filled with metals and other alloys, such as copper or silver to produce a nice plate color.

Menyinggi – the metal base material is melted back to be printed into a blade or round shape. There are three forms of gamelan that are made at this stage, namely, the long form (dawan), the long semicircle, and the cebongan form. To maintain sacredness, usually at this stage flower water is used to soak the gamelan that has been printed. Menempa – the gamelan that has been printed then goes into the forging or shaping stage to produce a perfect shape. The forging stage is the most complex stage in the gamelan-making process. In this stage, the process is carried out by people who really understand the ins and outs of gamelan, considering that the forging process is not done carelessly, but uses various hitting techniques using various kinds of hammers.

Membabar – the forged gamelan is then examined again at the spreading stage. At this stage, if there are still defects in the shape, it will be corrected again.

Melaras – there is one more important process that must be done to produce a perfect gamelan set, namely the process of adjusting the scales. Therefore, one more stage is needed to produce a gamelan with perfect physical and function, that stage is to adjust the scale.

After adjusting to the scale, the blades and circles are ready to be installed in the cage. It is at this stage that the manufacture of various gamelan instruments has been physically and functionally completed. Some craftsmen, although rarely found, complement the making of gamelan with various rituals, such as fasting and providing offerings. This is of course to produce a gamelan that is not only perfect physically and functionally, but also philosophically.

Gamelan production centers are spread across the islands of Java and Bali. These gamelan producers have exported hundreds and supplied gamelan all over the world. Several gamelan production centers are located in Sukoharjo, Boyolali, Wonogiri, Nganjuk, Magetan, Bantul, Ponorogo, Klaten, Banyuwangi, Gunung Kidul, Cimahi, Bogor, Gianyar, and Klungkung.

Influence on Western music

The gamelan has been appreciated by several western composers of classical music, most famously Claude Debussy, who heard a Javanese gamelan in the premiere of Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray's Rhapsodie Cambodgienne at the Paris Exposition of 1889 (World's Fair). The work had been written seven years earlier in 1882, but received its premiere only in 1889. The gamelan Debussy heard in it was in the slendro scale and was played by Central Javanese musicians.[52] Despite his enthusiasm, direct citations of gamelan scales, melodies, rhythms, or ensemble textures have not been located in any of Debussy's own compositions. However, the equal-tempered whole tone scale appears in his music of this time and afterward,[53] and a Javanese gamelan-like heterophonic texture is emulated on occasion, particularly in "Pagodes", from Estampes (solo piano, 1903), in which the great gong's cyclic punctuation is symbolized by a prominent perfect fifth.

The composer Erik Satie, an influential contemporary of Debussy, also heard the Javanese gamelan play at the Paris Exposition of 1889. The repetitively hypnotic effects of the gamelan were incorporated into Satie's Gnossienne set for piano.[54]

Direct homages to gamelan music are to be found in works for western instruments by John Cage, particularly his prepared piano pieces, Béla Bartók, Francis Poulenc, Leopold Godowsky, Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Bronislaw Kaper and Benjamin Britten. Colin McPhee, Lou Harrison and Claude Vivier would travel to Bali and Java to document the theory of gamelan, and subsequently incorporated it in their compositions. In more recent times, American composers such as Henry Brant, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Dennis Murphy, Loren Nerell, Michael Tenzer, Evan Ziporyn, Daniel James Wolf and Jody Diamond as well as Australian composers such as Peter Sculthorpe, Andrew Schultz, Paul Grabowsky and Ross Edwards have written several works with parts for gamelan instruments or full gamelan ensembles. Several New Zealand composers have composed for gamelan or incorporated elements of gamelan into their music such as Jack Body, Gareth Farr and Anthony Ritchie.[55]

I Nyoman Windha is among contemporary Indonesian composers who have written compositions using western instruments along with Gamelan. Hungarian composer György Ligeti wrote a piano étude called Galamb Borong influenced by gamelan. Avant-garde composer Harry Partch, one of America's most idiosyncratic composers, was also influenced by Gamelan, both in his microtonal compositions and the instruments he built for their performance[56]

In jazz, the music of Don Cherry, especially his 1968 record Eternal Rhythm, shows influences of gamelan music.

American folk guitarist John Fahey included elements of gamelan in many of his late-1960s sound collages, and again in his 1997 collaboration with Cul de Sac, The Epiphany of Glenn Jones. Influenced by gamelan,[57] Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew used rhythmically interlocking guitars in their duets with each other in the 1981–1984 trilogy of albums (Discipline, Beat, Three of a Perfect Pair) by rock band King Crimson[58][59] and with The League of Crafty Guitarists.[60] The gamelan has also been used by British multi-instrumentalist Mike Oldfield at least three times, "Woodhenge" (1979), "The Wind Chimes (Part II)" (1987) and "Nightshade" (2005).

On the debut EP of Sonic Youth the track 'She's not Alone' has a gamelan timbre. Experimental pop groups The Residents, 23 Skidoo (whose 1984 album was even titled Urban Gamelan), Mouse on Mars, His Name Is Alive, Xiu Xiu, Macha, Saudade, The Raincoats and the Sun City Girls have used gamelan percussion. Avant-garde performance band Melted Men uses Balinese gamelan instruments as well as gamelan-influenced costumes and dance in their shows. The Moodswinger built by Yuri Landman gives gamelan–like clock and bell sounds, because of its 3rd bridge construction. Indonesian-Dutch composer Sinta Wullur has integrated Western music and gamelan for opera.

Influence on contemporary music

In contemporary Indonesian music scene, some groups fuse contemporary westernized jazz fusion music with the legacy of traditional ethnic music traditions. In the case of Krakatau and SambaSunda, the bands from West Java, the traditional Sundanese kacapi suling and gamelan degung Sunda orchestra is performed alongside drum set, keyboard and guitars. Other bands such as Bossanova Java fused Javanese music with bossa nova, while the Kulkul band fuse jazz with Balinese gamelan.

The Indonesian singer Anggun often incorporated in her works Indonesian traditional tunes from the gamelan and tembang style of singing. Typical gamelan tunes can be traced in several songs in her album Snow on the Sahara such as "Snow on the Sahara", "A Rose in the Wind", and also in her collaboration works with Deep Forest on "Deep Blue Sea" on their 2002 album, Music Detected. Philippine-born Indonesian singer Maribeth Pascua also features gamelan tunes in her songs Denpasar Moon and Borobudur.

Beyond Indonesia, gamelan has also had an influence on Japanese popular music, specifically the synthpop band Yellow Magic Orchestra. Their 1981 record Technodelic,[61] one of the first albums to heavily rely on samples and loops, made use of gamelan elements and samples. Yellow Magic Orchestra member Ryuichi Sakamoto also used gamelan elements for his soundtrack to the 1983 British-Japanese film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,[62] which won him the 1983 BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.[63]

Many listeners were introduced to the sounds of gamelan by the popular 1988 Japanese anime film Akira. Gamelan elements are used in this film to punctuate several exciting fight scenes, as well as to symbolize the emerging psychic powers of the tragic hero, Tetsuo. The gamelan in the film's score was performed by the members of the Japanese musical collective Geinoh Yamashirogumi, using their semar pegulingan and jegog ensembles, which were also used in the previous album, Ecophony Rinne. Gamelan and kecak are also used in the soundtrack to the video games Secret of Mana, Sonic Unleashed, and Hotline Miami 2. The two opening credits of 1998 Japanese Anime Neo Ranga use Balinese music (Kecak and Gamelan gong kebyar). Each "waking up" of Ranga in the anime uses the Gong Kebyar theme. The musical soundtrack for the Sci Fi Channel series Battlestar Galactica features extensive use of the gamelan, particularly in the 3rd season,[64] as do Alexandre Desplat's scores for Girl with a Pearl Earring and The Golden Compass. James Newton Howard, who composed Disney's 2001 feature film Atlantis: The Lost Empire, chose Gamelan for the musical theme of the Atlanteans.[65]

Loops of gamelan music appear in electronic music. An early example is the Texas band Drain's album Offspeed and In There, which contains two tracks where trip-hop beats are matched with gamelan loops from Java and Bali and recent popular examples include the Sofa Surfers' piece Gamelan, or EXEC_PURGER/.#AURICA extracting, a song sung by Haruka Shimotsuki as part of the Ar tonelico: Melody of Elemia soundtracks.

Gamelan influences can also be heard in the 2004 award-winning pop song, Pulangkan, a theme from the gamelan-cultural related film Pontianak Harum Sundal Malam by Malaysian songbird Misha Omar and also the 2006 hip hop song, Tokyo Drift (Fast & Furious), by Teriyaki Boyz.

In the Regular Show episode "150-Piece Kit", a gamelan is mentioned to be part of the eponymous kit.

Gamelan outside Indonesia

Gamelan is widely known in Indonesia and abroad. There are many gamelan groups outside Indonesia. This is due to several factors like Indonesian migration (Javanese, Balinese, or Sundanese) and cultural interest, which brought and introduced gamelan abroad. The government of Indonesia is also actively promoting culture abroad through cultural missions and actively opening Darmasiswa[66] Scholarships for foreign students and lecturers who want to learn Indonesian culture, one of the most preferred is Gamelan. Indonesia has exported hundreds of gamelans and supplied gamelan all over the world. Gamelan has spread to almost all continents such as America (United States,[67] Mexico, Canada, Suriname), Europe[68] (United Kingdom, Russia, Belgium, Czech Republic, Italy, France, Spain, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, Netherland, Poland, Portugal), Asia (Singapore,[69] Malaysia, Thailand, China,[70] Japan, Korea), Australia and New Zealand.[71]

- Some of the gamelan Groups Outside Indonesia

-

Kyai Barleyan, a Javanese gamelan at Oberlin College in Ohio. Acquired in 1970, it is believed to be the third-oldest gamelan in use in the United States.

-

Gamelan Son of Lion, a Javanese-style iron American gamelan based in New York City that is devoted to new music, playing in a loft in SoHo, Manhattan, United States in 2007

-

Sundanese Gamelan Degung being played in Museo Nacional de las Culturas Mexico, Indra Swara Gamelan Group, on 2 April 2018

Gallery

- Gamelan ensemble

-

Golek Ayun-Ayun Dance performance accompanied by gamelan ensemble at Bangsal Sri Manganti Keraton Yogyakarta.

-

The Sundanese Jaipongan dance performance accompanied by a gamelan ensemble in West Java Pavilion, Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Jakarta.

-

Gamelan ensemble (or gambelan in Balinese term) accompanying barong performance (Bali lion dance) at Garuda Wisnu Kencana cultural complex, Bali, Indonesia.

-

Telek (masked) dance accompanied by gamelan ensemble in Bali, between 1950 and 1957.

-

Wayang wong performance accompanied by Gamelan in Java, between 1890 and 1916.

-

A gamelan ensemble consisting of children in a temple complex in Bali, between 1910 and 1920.

-

Children practiced dance with gamelan at Kebun Dalem Semarang, Dutch east Indies, circa 1867.

-

A gamelan set in an exhibition at the museum of the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (Now, National Museum of Indonesia), Batavia, circa 1896.

-

Gamelan Kaduk Manis Rengga (sacred gamelan) from Kraton Surakarta, Java, 2003.

-

Gamelan Sekati (One of Some Javanese Sacred Gamelan in the Keraton Yogyakarta) is being played to accompany Sekaten Ceremony in front of Kauman Great Mosque in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, on 27 April 2004.

-

Gamelan Nyi Asep Mangsa, Indra Swara, México, on 27 March 2015.

-

A gamelan ensemble as depicted on the obverse of the 1979-issue 10,000 rupiah banknote

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Learn the History Behind Gamelan, Indonesian Music and Dance". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1405881180.

- ^ "Gamelan". Cambridge. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Gamelan". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ a b Sumarsam (1998). Introduction to Javanese Gamelan Archived 14 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Middletown.

- ^ Bramantyo Prijosusilo, 'Indonesia needs the Harmony of the Gamelan' Archived 15 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Globe, 22 February 2011. [verification needed]

- ^ "Warisan Budaya Takbenda, Penetapan". Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Education and Culture of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Gamelan". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "History and Etymology for gamelan". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ a b Lindsay, Jennifer (1992). Javanese Gamelan, p.10. ISBN 0-19-588582-1.

- ^ "Indonesia For Beginners: Priangan and Gamelan Degung". The Attic. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Lindsay (1992), p.35.

- ^ Lentz, 5.

- ^ R.T. Warsodiningrat, Serat Weda Pradangga. Cited in Roth, A. R. New Compositions for Javanese Gamelan. University of Durham, Doctoral Thesis, 1986. Page 4.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Alat-Alat Musik Borobudur". YouTube.

- ^ "Selonding, the Sacred Gamelan from Ancient Village". Ubud Community. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Learn Ancient Gamelan Selonding at Mekar Bhuana". Mekar Bhuana. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Seni Musik Kasunanan Surakarta, Surakarta Hadingrat". Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Mengenal Gamelan Keraton Yogyakarta, 14 August 2018". Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Reyog Ponorogo,1980 froom book". Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Roth, 4–8

- ^ "Gamelan Sakati". Kabupaten Cirebon. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Kisah Gamelan Abad ke-15 Peninggalan Sunan Gunung Jati". Sudirman Wamad. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Gamelan Peninggalan Sunan Drajat di Lamongan Dikonservasi". Eko Sudjarwo. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "GAMELAN SEKATEN DAN PENYEBARAN ISLAM DI JAWA". Joko Daryanto. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Gamelan Tertua Keraton Yogyakarta Diarak" (in Indonesian). viva.co.id. 30 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Museum Prabu geusan Ulun". Kabupaten Sumedang. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Gamelan Istimewa Koleksi Museum di Sumedang, Melanglangbuana Hingga Eropa dan Amerika sebelum Diserahkan ke Bupati". Adang Jukardi. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Sari Oneng, Gamelan Sukabumi yang Tampil di Peresmian Menara Eiffel Paris". Oksa Bachtiar Camsyah. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Gamelan Berusia 400 Tahun Ini Pernah Pentas Saat Peresmian Menara Eiffel, Kini Ditata Ulang". Aam Aminullah. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Musik Gamelan di Luar Angkasa". Rahadian Rundjan. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Mengenal Gending Ketawang Puspawarna, Musik Jawa yang Dikirim hingga ke Luar Angkasa". Shani Rasyid. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Ganug Nugroho Adi, 'Ki Sarojo: Gamelan-making maestro' Archived 8 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 7 June 2012; Ganug Nugroho Adi, 'Forging gamelan in Central Java' Archived 15 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 11 July 2012.

- ^ Colin McPhee, Music in Bali. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966.

- ^ "Listening to Balinese Gamelan: A Beginners' Guide Archived 9 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine" from Connexions.com retrieved 20 January 2012

- ^ Sumarsan. Gamelan: cultural interaction and musical development in central Java. University of Chicago Press, 2nd Edition, 1996. page 156.

- ^ Lindsay, Jennifer. Javanese Gamelan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979. Pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-19-580413-9

- ^ For example, in Sorrell, Neil. A Guide to the Gamelan. United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1990.

- ^ "Gamelan Bali, Seni Musik". Encyclopedia Jakarta. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Mengenal Gamelan Keraton Yogyakarta". Keraton Yogyakarta. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Kartomi, Margaret (1990). On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. University of Chicago Press, p. 91.

- ^ "Gamelan Jawa: Cikal Bakal Gema Bunyi dari Masa Jawa Kuno". Gubug Wayang. November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Sejarah Gamelan Jawa & Perkembangannya". kompasiana. 19 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Gambelan (Gamelan) Bali – Ensambel Musik Tradisional Khas Budaya Bali". blogkulo. 26 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Broughton, 420

- ^ Lindsay, 45

- ^ "UPACARA TRADISIONAL SEKATEN". Provinsi Yogyakarta. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ For a discussion of dance in Central Java in Surakarta, see Ganug Nugroho Adi, 'Dancing at the Mangkunegara' Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 30 May 2012.

- ^ Broughton, Simon, et al., eds. World Music: The Rough Guide. London: The Rough Guides, 1994. ISBN 1-85828-017-6. Page 419–420.

- ^ Broughton, 421.

- ^ Roth, 17

- ^ Neil Sorrell. A Guide to the Gamelan. London: Faber and Faber, 2000. Pages 2–7 discuss the incident, about which much remains uncertain. In particular, it is unknown whether they played the Cirebonese instruments that the Paris Conservatoire received in 1887, which would be substantially different from their ordinary set, or if they brought their own set.

- ^ Neil Sorrell. A Guide to the Gamelan. London: Faber and Faber, 2000. Although the five notes of the slendro set are closest in pitch to a pentatonic scale, this scale would have been familiar from other folk sources, as it is a common scale worldwide. It is the equally tempered whole-tone scale that is more analogous of the slendro scale.

- ^ Orledge, RobertSatie the Composer (Music in the Twentieth Century)Cambridge University Press (26 October 1990)

- ^ Johnson, Henry (June 2008). "Composing Asia in New Zealand: gamelan and creativity" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies. 10 (1): 54–84. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Western Artists and Gamelan Archived 2014-03-07 at the Wayback Machine", CoastOnline.org.

- ^ P. 268: Martin, Bill (1997). Listening to the future: The time of progressive rock, 1968-1978. Open Court. p. 376. ISBN 0-8126-9368-X.

- ^ Tamm (2003, Chapter 10): Tamm, Eric (2003) [1990], Robert Fripp: From crimson king to crafty master (Progressive Ears ed.), Faber and Faber (1990), ISBN 0-571-16289-4, Zipped Microsoft Word Document, archived from the original on 26 October 2011, retrieved 26 October 2011

- ^ Bruford (2009, p. 148): Bruford, Bill (2009). Bill Bruford: The autobiography: Yes, King Crimson, Earthworks, and more. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-23-7.

- ^ "Live! Robert Fripp and The League of Crafty Guitarists (Review)". Audio. Vol. 71. Radio Magazine. 1987. p. 98. LCCN 26018838. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Carter, Monica (30 June 2011). "It's Easy When You're Big In Japan: Yellow Magic Orchestra at The Hollywood Bowl". The Vinyl District. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ Pulvers, Roger (1 July 2012). "Ryuichi Sakamoto reminds Japanese what's the score on nuclear blame". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (1983) at IMDb

- ^ "SoundtrackNet 2/28/07 article". Soundtrack.net. 28 February 2007. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ Various cast and crew members (29 January 2002). Atlantis: The Lost Empire—Supplemental Material (DVD). Disc 2 of 2 (Collector's ed.). Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. UPC 786936163872.

- ^ Darmasiswa Scholarship Program 2019. Jakarta: Kementrian Luar Negeri, 2019.

- ^ List of gamelan ensembles in the United States. United States: Wikipedia, 2020.

- ^ Jody Diamond and Barbara BenaryGamelan Groups in Europe. American Gamelan Instite, 2005.

- ^ Pachitan Gamelan Orchestra is Formed. Singapore, 1991.

- ^ "Mahasiswa China pentaskan musik gamelan". www.antaranews.com. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Gamelan ensembles". New Zealand School of Music. Victoria University of Wellington. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

Further reading

Javanese gamelan

- Gamelan: Cultural Interaction and Musical Development in Central Java (1995) by Sumarsam, ISBN 0-226-78010-4 (cloth) 0226780112 (paper)

- Music in Central Java: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (2007) by Benjamin Brinner, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0-19-514737-5 (paper)

- Music in Java: History Its Theory and Its Technique (1949/1973) edited by Jaap Kunst, ISBN 90-247-1519-9. An appendix of this book includes some statistical data on intervals in scales used by gamelans.

- A Gamelan Manual: A Player's Guide to the Central Javanese Gamelan (2005) by Richard Pickvance, Jaman Mas Books, London, ISBN 0-9550295-0-3

- Kartomi, Margaret J. (2002). Eastman Studies in Music #15; The Gamelan Digul and the Prison Camp Musician Who Built It : An Australian Link with the Indonesian Revolution (hardcover, bibliography, index, with CD). University of Rochester Press. p. 123. ISBN 1580460887.

When the prison camp at Tanah Merah, on the Digul river in West Papua, was evacuated by the Dutch in 1943, the prisoners brought with them to Australia a gamelan they had constructed.

- Shadow Music of Java produced by Karl Signell, Rounder CD 5060.

Balinese gamelan

- Balinese Music (1991) by Michael Tenzer, ISBN 0-945971-30-3. Included is an excellent sampler CD of Balinese Music.

- Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth-Century Balinese Music (2000) by Michael Tenzer, ISBN 0-226-79281-1 and ISBN 0-226-79283-8.

- Music in Bali (1966) by Colin McPhee. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Music in Bali: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (2007) by Lisa Gold, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0-19-514149-0 (paper)

External links

- Introduction to Gamelan Music by Qehn, Javanese gamelan only.

- Balinese and Javanese Gamelan Archived 9 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine written in 2005. Most links do not work as of January 2017.

- Listening to Balinese Gamelan: A Beginners' Guide from Connexions accessed 20/01/2012

- A curated collection of Javanese and Balinese gamelan music – by John Noise Manis