Luigi Tenco

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. (May 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Luigi Tenco | |

|---|---|

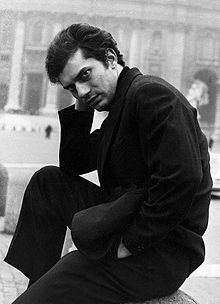

Tenco in 1967, his last known picture taken before his death | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Born | 21 March 1938 Cassine, Italy |

| Origin | Genoa, Italy |

| Died | 27 January 1967 (aged 28) Sanremo, Imperia, Italy |

| Genres | |

| Occupation | Singer-songwriter |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1953–1967 |

| Labels | |

Luigi Tenco (21 March 1938 – 27 January 1967) was a popular Italian singer-songwriter.

He died щт the night between 26 and 27 January, 1967, after performance at Sanremo Music Festival. His death was ruled to be the result of suicide, but even decades later, a plethora of evidence in favour of murder was the reason to reopen the investigation twice.

Biography

Tenco was born in Cassine (province of Alessandria) in 1938, the son of Teresa Zoccola. He never knew his father. Teresa Zoccola was married to Giuseppe Tenco, they had a son, Valentino, but eventually the couple separated and Teresa moved to Cassine. It has been rumored that Luigi Tenco was the fruit of the extramarital relationship of his mother and an unidentified man of the family Micca, for whom she worked at the time: the sixteen-year-old son or his father. When Zoccola discovered the pregnancy, she returned to Cassine. The boy was given the name of her official husband, Tenco, who died in a work accident while she was several months pregnant.[1]

Tenco spent his childhood in Cassine and Ricaldone until 1948, when he moved to Liguria, first to Nervi and then to Genoa, where his mother had a wine shop called Enos in the quarter of La Foce. He developed an early interest in music and self-taught playing guitar, clarinet and saxophone. During high school, Tenco founded the Jelly Roll Morton Boys Jazz band, in which Tenco played the clarinet and another singer, later to become famous, Bruno Lauzi, the banjo. Gino Paoli, who would become one of Italy's most famous singers and songwriters as well, also played with Tenco in the band he was later involved in, I Diavoli del Rock (The Rock Devils).[1]

Tenco made his debut in the world of Italian professional music with the band I Cavalieri (The Knights), which included Giampiero Reverberi and Enzo Jannacci amongst others. During this period he used the pseudonym Gigi Mai. In 1961 Tenco released his first single under his real name, entitled Quando ("When").

He started university studying electronic engineering, trying to comply with the wishes of his mother and brother. He twice failed the Analytic and Projective Geometry exam (a course he took with professor Eugenio Giuseppe Togliatti, the elder brother of Communist party leader Palmiro Togliatti). Later he was enrolled in political science, where he gave only two exams.[1]

Tenco was interested in cinema and videomaking. In 1962 he began a short-lived cinematic experience, with Luciano Salce's movie La Cuccagna. He also collaborated on the soundtrack of the film, and introduced his friend Fabrizio De André (unknown at the time) through the song La ballata dell'eroe (Ballad for a hero).[2] Director Luigi Comencini considered Tenco for the role of Bube in his film La ragazza di Bube, based on Carlo Cassola's novel. He ultimately chose George Chakiris, the West Side Story star, instead. During this period Tenco formed a strong friendship with the Genoese anarchist poet Riccardo Mannerini. In 1963, however, his friendship with Gino Paoli broke up, due to a troubled relationship with the actress Stefania Sandrelli.

Tenco's first LP, Ballate e Canzoni, was released in 1962. One of the songs, "Cara Maestra" ("Dear Teacher"), was censored by the then-thriving Italian media censorship. For this song, he was banned from Rai for two years.[1][3] The censors struck again in the following year, against his songs "Io sì" ("I Would"), considered too sexually explicit, and "Una brava ragazza" ("A Good Girl"), where Tenco express his admiration for a '60s "bad girl". In September 1964, he released "Ho capito che ti amo", a song written by him with musical arrangement by Ezio Leoni. It was released on the Italian record label Jolly as Side A of a 45 rpm, side B being "Io lo so già".[4] In Argentina, "Ho capito che ti amo" was the soundtrack of the popular soap opera El amor tiene cara de mujer.

In 1966, enduring a period of compulsory military service, he released "Un giorno dopo l'altro" (One Day after Another) for RCA. The military service did not stop him from traveling to Argentina together with Gianfranco Reverberi to meet the fans of El amor tiene cara de mujer. How he managed to arrive in Argentina while his passport was still in possession of the Italian Army is unknown. Moreover, under the military service one was not allowed to leave Italy and the punishment was detention, which he did not experience according to his service record book.[5]

In Rome during the same year, he met and befriended the Italian-French singer Dalida. Many implied that they became lovers, however, Tenco had a fiancee, Valeria, a decade after his death many letters to her were discovered. Tenco's mother also confirmed that he treated Dalida only as a good friend.[1][6] Lino Patruno, a close friend of Tenco, described his relationship with Dalida as 'marketing trick'.[7]

1967 Sanremo Festival and death

In January 1967 Tenco took part in the Sanremo Music Festival 1967. It was rumoured that he participated against his will. On January 26, 1967, he performed the song "Ciao, amore, ciao" ("Bye Bye, My Love") with Dalida. The video of the performance is lost; however, the audio track, recorded from radio, survives.[8] That evening, Tenco sang badly and off time, presumably because he had taken barbiturates with alcohol shortly before the performance to cope with anxiety.[9] After the show, on the evening of the 26th, he was seen at the Nostromo restaurant together with Dalida, her ex-husband, other friends and colleagues. He left early, leaving the group behind.[10]

Approximately at 2 o'clock in the morning hours of 27 January 1967, Tenco was found dead in his room No. 219 at the Hotel Savoy by Dalida. Tenco died from a single gunshot wound to the head. His death was ultimately ruled a suicide.[11][12] However, due to multiple violations in the investigation, the case was reopened twice, still with a verdict of a suicide.[1][10]

Tenco was apparently upset after learning that his song had been eliminated from the final competition.[12] Several people, close to Tenco, witnessed that he was more upset with the corruption and bribery at the festival and planned to take a press-conference to unveil it all.[7]

Tenco was buried in Ricaldone. In 1974, the Tenco Award was instituted, and has been held every year since in Sanremo. Many of the most renowned Italian singer-songwriters from the 1970s explicitly declared the influence of Tenco on their work. Francesco De Gregori's album Bufalo Bill of 1976 contained a song, "Festival", about Tenco's suicide; it points out the hypocrisy with which the music establishment tried to minimize the dramatic event, to let the show go on.

The inquiry

In 2004, on TV program Domenica in, commissario Arrigo Molinari, the detective who followed the inquiry, when asked by host Paolo Bonolis, stated that he was sure that Tenco did not commit suicide and he defined his death: "a collective murder".[13] He also justified his own faults concerning the Tenco inquiry by declaring that he had been prevented from investigating properly. In 1967, upon learning of Tenco's death from Dalida, still in his own home, Molinari phoned ANSA and declared that the singer had killed himself. And this even before arriving at the Savoy and before the forensic team could intervene. Shortly after the quoted 2004 interview, Molinari was stabbed to death in his own hotel in Andora.[10]

In 1967, no autopsy had been done on the singer's corpse, no paraffine test, and no calligraphic analysis on the suicide note with which he explained his final gesture. Some police photographs from the scene, unedited and publicly shown only in 1994, showed that Tenco's body and face was bruised. On the back side of his head a trauma was evident, that forensics didn't confirm as related to post-mortem falling. Also, the concierge of the Savoy, who was asked if he had seen Tenco return that night, stated that the keys were not on the reception desk and not that he had seen Tenco return. Traces of sand were spotted on Tenco's hair, clothes and in his car, however some journalists confirmed that the car was washed before going to Nostromo.[10]

Dalida testified that on the night of 26 January, while she was still at the Nostromo, Dalida received a phone call from the Hotel Londra in Sanremo. She told the diners that she has been told that Tenco is at the Savoy and is feeling unwell. Strangely enough, Dalida did not rush to the Savoy, but makes a roundabout way; she bought cigarettes and then picked up her ex-husband, Lucien Morisse, and arrived at Savoy after 40 minutes, when it takes only 5, where she discovered Tenco's lifeless body.[10]

Notable is the fact that the alleged farewell note does not appear in the police report, as it was not found in room 219 on the night of death. In fact, the note came into the hands of the police from a third party. Initially it was in Dalida's room (No. 104) who gave it to Sergio Modugno (Tenco's friend) who passed it on to Piero Vivarelli (journalist friend of Tenco) who finally gave it to the Police. The note read: "I cared for the Italian public and I dedicated in vain five years of my life to them. I'm doing this not because I'm tired of life (I'm not) but as a gesture of dissent against the public who chose 'Io, tu e le rose' for the final night and against the commission that selected 'La rivoluzione'. I hope this will clear somebody's head." Later forensics detected word casts on the note, as if there had been at least another sheet, superimposed on the one found, with other words. The words in the casts are ‘gioco’ (game) and ‘già’ (already): game, in particular, would seem compatible with Tenco's intention to denounce clandestine betting, as he had already announced to his fiancée Valeria in the above-mentioned telephone call. One of the police photos of commissario Molinari, who lead the case, showed him standing on the scene with two sheets. Moreover, later the experts didn't confirm the signature on the note to be Tenco's, and mentioned a spelling mistake that couldn't be done by a native speaker of Italian who dealed with writing daily. The family didn't recognize the handwriting as Tenco's. As supposed by journalists, the alleged suicide note might in fact have been the last page of a document written by Tenco for a different aim.[14][10]

The Italian judicial system later began re-examining Luigi Tenco's suicide. It was pointed out that the bullet hole was on the left temple, while the singer was right-handed. On 15 February 2006, Italian police exhumed Tenco's body for further investigation.[15] The next day, results from the new autopsy and ballistics analysis were reported. According to Italian experts, what had been thought to be the entry hole on the left temple was actually the exit site. The bullet trajectory was said to be compatible with suicide.[11]

Nevertheless, criminologists Pasquale Ragone and Nicola Guarneri, in their book Le ombre del silenzio (The shadows of silence, 2013)[5] pointed out several incongruences between the shell casing of the bullet found in Tenco's room and the bullet Tenco's Walther PPK gun would eject. Professor of ballistic forensics Martino Farneti proved that they did not match. There was no proof nor official statement declaring that Tenco's Walther PPK was actually present in his room the night he died (the police registers show that the gun was actually found in his car), so Guarneri and Ragone think that Tenco might have been killed. The actual weapon might have been a Beretta 70, as it is possible to put a silencer on this type of gun (similar to a Walther PPK). In fact, the night Tenco died (allegedly in his hotel room), no one heard the sound of the gunshot, not even singer Lucio Dalla, whose room was next to Tenco's, nor did journalist Sandro Ciotti, whose room was in front of Tenco's.[5] However, in 1967 at Savoy only 3 meters from room 219 there were the door to the inner garden, exactly the one used by police to transport the body.[10]

In 1993-94, journalists Marco Buttazzi and Andrea Pomati rediscovered the file compiled by the police in 1967. In the attached photos, they saw that Tenco's body had his legs (from ankles to feet) positioned under a wooden cabinet; suspicious of the anomalous position of the corpse, they investigated further and found out that those photos do not depict the real crime scene. They interviewed the undertaker of the time who declared that commissario Arrigo Molinari, in charge of the investigation, had ordered the body to be immediately transferred to the morgue, even before the arrival of the forensic team; it was then taken back to the Savoy and reassembled to allow the photos to be taken and attached to the above-mentioned file.[10]

Music producer and friend Paolo Dossena stated that he drove Tenco's car from Rome (where the songwriter lived) to Sanremo and on the way, passing through a roadblock on the Aurelia, he discovered that Tenco had his Walther PPK in the dashboard of his car. He later confronted the songwriter who confessed that he took a gun because someone in the past few weeks had tried to drop him down a steep road near Santa Margherita Ligure while he was driving.[16]

At the beginning of the '90s Tenco's older brother Valentino met a woman, Valeria, who had in her possession several letters written by Tenco himself that would testify their love relationship started in 1964 and lasted until his death. In one of these letters, Tenco writes that his relationship with Dalida was nothing but a clumsy attempt to forget Valeria, who, months before, had left him. He describes Dalida as a woman: "spoiled, neurotic, ignorant, who rejects the idea of being defeated in her profession as in private life". Valentino Tenco identified those letters as written by his brother.[5]

Tributes

Shortly after Tenco's death, his friend and songwriter Fabrizio De André wrote for him the song Preghiera in gennaio (A prayer in January), where he describes a benevolent God welcoming those who committed suicide into Heaven, in spite of the moral condemnation of the bigots.

In 1999, the play Solitudini – Luigi Tenco e Dalida, written and directed by Maurizio Valtieri, was performed in Rome.

French journalist and novelist Philippe Brunel wrote a fiction book, La nuit de San Remo, in which he dramatises the arduous search for truth about Tenco's death.

In 2005, the French television channel TV5 carried a full-length dramatisation of the love affair of Tenco and Dalida. Tenco was played by Alessandro Gassman, while Dalida was played by Sabrina Ferilli.[5]

Discography

Albums

- 1962: Luigi Tenco

- 1965: Luigi Tenco

- 1966: Tenco

- Compilations / Unreleased materials

- 1972: Luigi Tenco

- 1972: Luigi Tenco canta Tenco, De André, Jannacci, Bob Dylan

- 1977: Agli amici cantautori

- 1984: Luigi Tenco

Extended plays

- 1967: Ti ricorderai di me...

- 1967: Se stasera sono qui

- 1969: Pensaci un po'

Singles

- 1959: "Mai"/"Giurami tu"

- 1959: "Mi chiedi solo amore"/"Senza parole"

- 1959: "Amore"/"Non so ancora" (as Gigi Mai)

- 1959: "Vorrei sapere perché"/"Ieri" (as Gigi Mai)

- 1960: "Tell Me That You Love Me"/"Love Is Here to Stay" (as Gordon Cliff)

- 1960: "Quando"/"Sempre la stessa storia" (as Dick Ventuno)

- 1961: "Il mio regno"/"I miei giorni perduti"

- 1961: "Quando"/"Triste sera"

- 1961: "Una vita inutile"/"Ti ricorderai"

- 1961: "Ti ricorderai"/"Quando"

- 1961: "Ti ricorderai"/"Se qualcuno ti dirà"

- 1961: "Quando"/"Se qualcuno ti dirà"/"Ti ricorderai"/"I miei giorni perduti"

- 1961: "Senza parole"/"In qualche parte del mondo"

- 1962: "Come le altre"/"La mia geisha"

- 1962: "In qualche parte del mondo"

- 1962: "Quello che conta"/"Tra tanta gente"/"La ballata dell'eroe"

- 1962: "Angela"/"Mi sono innamorato di te"

- 1962: "Quando"/"Il mio regno"

- 1963: "Io sì"/"Una brava ragazza"

- 1964: "Ragazzo mio"/"No, non è vero"

- 1964: "Ho capito che ti amo"/"Io lo so già"

- 1965: "Tu non hai capito niente"/"Non sono io"

- 1966: "Se sapessi come fai"/"Un giorno dopo l'altro"

- 1966: "Lontano lontano"/"Ognuno è libero"

- 1967: "Ciao amore, ciao"/"E se ci diranno"

- 1967: "Quando"/"Mi sono innamorato di te"

- 1967: "Ti ricorderai"/"Angela"

- 1967: "Guarda se io"/"Vedrai vedrai"

- 1967: "Io vorrei essere là"/"Io sono uno"

- 1967: "Se stasera sono qui"/"Cara maestra"

- 1968: "Pensaci un po'"/"Il tempo dei limoni"

- 1970: "Vedrai vedrai"/"Ah... l'amore l'amore"

- 1984: "Serenella"

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Luigi Tenco, 85 anni fa nasceva il grande cantautore italiano: la sua storia". Spettacolo Sky Tg24. 21 March 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Tenco, Luigi. "Luigi Tenco – La ballata dell'eroe". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021.

- ^ De Angelis & Deregibus 2013.

- ^ "HO CAPITO CHE TI AMO/IO LO SO GIÀ". Discografia Nazionale della canzone italiana (in Italian). Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Guarneri, Ragone (2013). Le ombre del silenzio. Castelvecchi.

- ^ Ascione, Arianna (27 January 2022). [L’eliminazione di «Ciao amore ciao» - Luigi Tenco, 55 anni fa la morte: il racconto delle sue ultime ore - Corriere.it "Luigi Tenco, 55 anni fa la morte: il racconto delle sue ultime ore"]. Corriere della sera. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b "Caso Luigi Tenco, Lino Patruno: «Fu omicidio e presto si saprà chi è l'assassino»". Corriere della sera. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Tenco, Luigi. "Ciao Amore Ciao live in Sanremo". YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 July 2011.

- ^ "Luigi Tenco, un suicidio che non ha mai convinto". Lecce news. 27 January 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sella, Filippo (8 November 2017). "Quanti misteri attorno al "suicidio" di Luigi Tenco e quante morti tra chi se ne occupò" [The mysteries of alleged suicide of Luigi Tenco and many deaths of those connected] (in Italian). Bergamo News. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b Campion, Chris (23 January 2008). "Unsung Heroes No.4 – Luigi Tenco". Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Festival Loser Kills Himself". The New York Times. 28 January 1967. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ "Intervista di Paolo Bonolis ad Arrigo Molinari". YouTube. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014.

- ^ "La morte di Luigi Tenco: si riparla dell'ipotesi dell'omicidio". Quotidiano Piemontese. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Tenco: confermata l'ipotesi del suicidio". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 16 February 2006. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Testimonianza di Paolo Dossena". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021.

Sources

- Colonna, Aldo (2017). Vita di Luigi Tenco. Bompiani. ISBN 9788858774380.

- De Angelis, Enrico; Deregibus, Enrico (2013). Il mio posto nel mondo. BUR. ISBN 978-88-586-4864-3.

External links

- 1938 births

- 1967 suicides

- People from Cassine, Piedmont

- Italian male singer-songwriters

- Italian singer-songwriters

- Suicides by firearm in Italy

- Dalida

- 20th-century Italian male actors

- 20th-century Italian male singers

- Italian jazz musicians

- Italian male jazz musicians

- Italian jazz clarinetists

- Italian jazz saxophonists

- Philips Records artists

- 1967 deaths