Aphrodite of Knidos

| Aphrodite of Knidos | |

|---|---|

| Venus Pudica | |

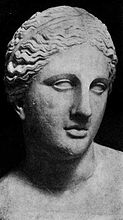

The Ludovisi Cnidian Aphrodite, Roman marble copy (torso and thighs) with restored head, arms, legs and drapery support | |

| Artist | Praxiteles |

| Year | 4th century BC |

| Movement | Greek late classical period |

| Dimensions | 205 cm (81 in) |

The Aphrodite of Knidos (or Cnidus) was an Ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess Aphrodite created by Praxiteles of Athens around the 4th century BC. It was one of the first life-sized representations of the nude female form in Greek history, displaying an alternative idea to male heroic nudity. Praxiteles' Aphrodite was shown nude, reaching for a bath towel while covering her pubis, which, in turn leaves her breasts exposed. Up until this point, Greek sculpture had been dominated by male nude figures. The original Greek sculpture is no longer in existence; however, many Roman copies survive of this influential work of art. Variants of the Venus Pudica (suggesting an action to cover the breasts) are the Venus de' Medici and the Capitoline Venus.

Original

The Aphrodite of Knidos was a marble carving of the goddess Aphrodite by the sculptor Praxiteles, which was bought by the people of Knidos in the middle of the 4th century BC.[1] The earliest text to mention the Aphrodite is Pliny the Elder's Natural History,[2] which reports that Praxiteles carved two sculptures of Aphrodite, one clothed and one nude; the clothed one was bought by the people of Kos and the Knidians bought the nude one.[3] The statue was set up as the cult statue for the Temple of Aphrodite at Knidos. It depicted the goddess Aphrodite as she prepared for the ritual bath that restored her purity, discarding her drapery with one hand, while modestly shielding herself with the other. The placement of her hands obscures her pubic area, while simultaneously drawing attention to her exposed upper body. The statue is famed for its beauty, and is designed to be appreciated from every angle.

Because the various copies show different body shapes, poses and accessories, the original can only be described in general terms. It depicted a nude woman, the body twisting in a contrapposto position, with its weight on the right foot. Most copies show Aphrodite covering her pubic area with her right hand, while the left holds drapery which, along with a vase, helps support the figure.[4] Almost all copies show the head of the sculpture turning to the left.[5]

The female nude appeared nearly three centuries after the earliest nude male counterparts in Greek sculpture, the kouros; the female kore figures were clothed. Previously nudity was a heroic uniform assigned only to men. When making the Aphrodite of Knidos, Spivey argues that her iconography can be attributed to Praxiteles creating the statue for the intent of being viewed by male onlookers.[6] Overwhelming evidence from aggregations suggests that the Knidian sculpture was meant to evoke male responses of sexuality upon viewing the statue.[6] The Aphrodite of Knidos established a canon for the proportions of the female nude,[7][better source needed] and inspired many copies, the best of which is considered to be the Colonna Knidia in the Vatican's Pio-Clementine Museum. A Roman copy, it is not thought to match the polished beauty of the original, which was destroyed in a disastrous fire at Constantinople in 475.[citation needed]

Praxiteles was alleged to have used the courtesan Phryne as a model for the statue, which added to the gossip surrounding its origin. The statue became so widely known and copied that in a humorous anecdote the goddess Aphrodite herself came to Knidos to see it. A lyric epigram of Antipater of Sidon[8] places a hypothetical question on the lips of the goddess herself:

A similar epigram is attributed to Plato:

When Cypris saw Cypris at Cnidus, "Alas!" said she; "where did Praxiteles see me naked?"

According to an epigram from Roman poet Ausonius, Praxiteles never saw what he was not meant to see, but instead sculpted Aphrodite as Ares would have wanted.[10]

Temple in Knidos

The temple of Aphrodite in Knidos where the statue was displayed is described by two ancient sources, Pliny the Elder in his Natural History and Pseudo-Lucian in his Amores.[11] According to Pliny, the sculpture was housed in a small building, open on all sides – by which he likely meant a monopteros, a colonnade with a roof but no walls.[12] In the description given by Pseudo-Lucian, on the other hand, the building which housed the statue is described as having two doors, and suggests a more confined space than Pliny's description.[13] In excavations at Knidos between 1969 and 1972, Iris Love discovered the remains of a round building which she identified as the temple of Aphrodite. This included a stone inscribed with the letters PRAX, which Love suggested was a statue base for the Knidian Aphrodite.[14]

The statue became a tourist attraction in spite of being a cult image, and a patron of the Knidians. Nicomedes I of Bithynia offered to pay off the enormous debts of the city of Knidos in exchange for the statue, but the Knidians rejected his offer. The statue would have been polychromed,[15] and was so lifelike that it even aroused men sexually, as witnessed by the tradition that a young man broke into the temple at night and attempted to copulate with the statue, leaving a stain on it. An attendant priestess told visitors that upon being discovered, he was so ashamed that he hurled himself over a cliff near the edge of the temple.[16] This story is recorded in the dialogue Erotes (section 15), traditionally attributed to Lucian of Samosata.[17]

Influence

The Knidian Aphrodite has not survived. Possibly the statue was removed to Constantinople (modern Istanbul), where it was housed in the Palace of Lausus; in 475, the palace burned and the statue was lost. It was one of the most widely copied statues in the ancient world, so a general idea of the appearance of the statue can be gleaned from the descriptions and replicas that have survived to the modern day. For a time in 1969, the archaeologist Iris Love thought she had found the only surviving fragments of the original statue, which are now in storage at the British Museum. The prevailing opinion of archaeologists is that the fragment in question is not of the Knidia, but of a different statue.

- Probably the most faithful replica of the statue is the Colonna Venus conserved in the Museo Pio-Clementino, part of the collections of the Vatican Museums.

- The Kaufmann Head, found at Tralles, purchased from the C. M. Kaufmann collection, Berlin, and conserved in the Musée du Louvre, is thought to be a very faithful Roman reproduction of the head of the Knidian Aphrodite.[18]

- At Hadrian's Villa near Tivoli in Italy, there is a second-century recreation of the temple at Knidos with a fragmentary replica of the Aphrodite standing at the center of it, generally matching descriptions in ancient accounts of how the original was displayed.

- At the Prado Museum.

As well as more or less faithful copies, the Aphrodite of Knidos also influenced various variations, which include:

- the Capitoline Venus (Capitoline Museums, Rome)

- the Barberini Venus

- the Borghese Venus

- the Satala Aphrodite (British Museum), considered a replica by Zhores Khachatryan[19]

- the Aphrodite of Melos (the Venus de Milo, Louvre, Paris)

- the Venus de' Medici (Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

- the Esquiline Venus (Capitoline Museum, Rome)

- Venus of the Esquiline type (Louvre, Paris)[20]

- the Crouching Venus (Louvre, Paris and British Museum, London)

- the Aphrodite Kallipygos (aka Venus Kalypygos, Museo Archeologico Nazionale Napoli, Naples)

- the Venus Victrix (Uffizi Gallery)

- Venus Urania (Uffizi Gallery)

- The Mazarin Venus, named after Cardinal Mazarin (now in the J. Paul Getty Museum)

- An example with added figures of Pan and Cupid at the Athens National Archaeological Museum.[21]

- The Venus Felix at the Vatican Museums, a possible variation of the type.[22]

-

The Colonna Venus

-

The Venus de' Medici, of the variant Venus Pudica type where both hands cover the body.

-

Back view of the Aphrodite of Knidos, Roman copy, 4th century AD

-

Aphrodite of Knidos, Roman copy, 4th century AD

Notes

- ^ Havelock, Christine Mitchell (1995). The Aphrodite of Knidos and her Successors: a Historical Review of the Female Nude in Greek Art. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 1, 9. ISBN 0-472-10585-X.

- ^ Havelock, Christine Mitchell (1995). The Aphrodite of Knidos and her Successors: a Historical Review of the Female Nude in Greek Art. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-472-10585-X.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 36.20

- ^ Seaman 2004, p. 538.

- ^ Seaman 2004, p. 542.

- ^ a b Spivey, Nigel (2013). "8. Revealing Aphrodite". Greek Sculpture. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. doi:10.1017/9780521760317.010. ISBN 9781316179628. S2CID 239158305.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (1996). "The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and the Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient Art". Oxford Art Journal. 19 (2): 4. doi:10.1093/oxartj/19.2.3. JSTOR 1360725. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Antipater, Greek Anthology XVI.168 [The author of this poem is listed as anonymous in the Loeb edition (The Greek Anthology Vol. V., p. 257).]

- ^ Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D S, eds. (1997). "Epigrams". Plato: Complete Works. Translated by Edmonds, J. M. Indianapolis: Hackett. p. 1744. ISBN 9780872203495.

- ^ Ausonius (March 2, 2015). Epigrams. Translated by N. M. Kay. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 122. ISBN 9780715631058.

- ^ Montel 2010, pp. 254–258.

- ^ Montel 2010, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Montel 2010, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Montel 2010, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Havelock, p. 13. Pliny recounts that Praxilites valued most the sculptures of his that were painted by the hand of the Athenian Nikias, although he does not specifically link Nikias to the Knidian Aphrodite

- ^ Spivey, Nigel. "Revealing Aphrodite" from "Understanding Greek Culture". pp. 173–186.

- ^ See also the Hellenistic story of Pygmalion.

- ^ "The head from Martres Tolosanes and, especially, the so-called Kaufmann appear to me the best extant replicas." (Charles Waldstein, "A Head of Aphrodite, Probably from the Eastern Pediment of the Parthenon, at Holkham Hall", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 33 (1913:276–295 [283]); "general agreement on the genuineness of the Kaufmann Collection Aphrodite as a replica of the Cnidian Aphrodite" (Robert I. Edenbaum, "Panthea: Lucian and Ideal Beauty", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism" 25.1 (Autumn 1966:65–700 [69]

- ^ Khachatryan, Zhores (1985). "Անահիտ դիցուհու պաշտամունքն ու պատկերագրությունը Հայաստանում և նրա աղերսները հելլենիստական աշխարհի հետ" [The Cult and Iconography of Goddess Anahit in Armenia and Its Relations with the Hellenistic World]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1): 128.

- ^ "Louvre site des collections". collections.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Aphrodite & Pan – Ancient Greek Statue". www.theoi.com.

- ^ "Venus Felix – Ancient Greco-Roman Statue". www.theoi.com.

References

- Theodor Kraus. Die Aphrodite von Knidos. Walter Dorn Verlag, Bremen/Hannover, 1957.

- Leonard Closuit. L'Aphrodite de Cnide: Etude typologique des principales répliques antiques de l'Aphrodite de Cnide de Praxitèle. Éditions Pillet – Martigny, 1978.

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900. Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1981.

- Christine Mitchell Havelock. The Aphrodite of Knidos and Her Successors: A Historical Review of the Female Nude in Greek Art University of Michigan Press, 1995.

- Cyril Mango, "Antique Statuary and the Byzantine Beholder", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 17 (1963), pp. 53–75.

- Montel, Sophie (2010). "The Architectural Setting of the Knidian Aphrodite". In Smith, Amy C.; Pickup, Sadie (eds.). Brill's Companion to Aphrodite.

- Seaman, Kristen (2004). "Retrieving the Original Aphrodite of Knidos". Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Rendiconti Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche. 9. 15 (3).

External links

Media related to Aphrodite of Cnidus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aphrodite of Cnidus at Wikimedia Commons- Entry page for the Vatican Museums.

- James Grout: Aphrodite of Cnidus, part of the Encyclopædia Romana