Culture of Azerbaijan

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Azerbaijan |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

The culture of Azerbaijan (Template:Lang-az) combines a diverse and heterogeneous set of elements which developed under the influence of Iranic, Turkic and Caucasian cultures. Azerbaijani culture includes its cuisine, literature, folk art, and music.

History

Azerbaijan is the modern name of a historic, geographic region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, formerly known as Aran (or Ardan) by Persian empires and Albania by the Greeks. It is bounded by the Caspian Sea on the east, Dagestan on the north, Georgia on the northwest, Armenia and Turkey on the southwest, and Iran on the south. Although Azerbaijan is home to a number of ethnic groups, ten million people are Azerbaijanis.

The heritage, culture, and civilization of Azerbaijan have ancient and modern roots. Its people are believed to be descendants of ancient peoples who include indigenous Caucasian Albanian tribes, such as the Scythians and Alans, and the later Oghuz Turks.

Caucasian Albania

Caucasian Albanians are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of the land, north of the Aras, which is present-day Azerbaijan. Early arrivals included the Iranian Scythians during the 9th century BC.[1] The South Caucasus was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire around 550 BC. Zoroastrianism was already prevalent among the Medes in the lands surrounding the Aras. The Achaemenids were defeated by Alexander the Great in 330 BC. After the fall of the Seleucid Empire in Persia in 247 BC and its succession by the Parthian Empire, the Caucasian Albanians established a kingdom in the 1st century BC and remained largely independent under Parthian rule until the Sasanian Empire made the kingdom a province in 252 AD.[2][3] The Arsacid king Urnayr adopted Christianity as the state religion in the fourth century, and Caucasian Albania was a Christian state until the eighth century.[4][5] Sasanid control ended with their defeat by Muslim Arabs in 642.[6]

Islamic period

For centuries before Islam arrived in present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, the region was under Sassanid Iranian rule; before that, it was ruled by Parthian Iranians. Muslim Arabs defeated the Sassanids and the Byzantine Empire as they marched into the Caucasus. They made Caucasian Albania a vassal state after Christian resistance, led by Prince Javanshir, surrendered in 667. Between the ninth and 10th centuries, Arab authors referred to the region between the Kura and Aras as Arran.[a] Arabs from Basra and Kufa came to Aran, seized lands abandoned by the indigenous peoples, and became a land-owning elite.[7] Despite pockets of continued resistance, most inhabitants of Azerbaijan converted to Islam. During the 10th and 11th centuries, the Kurdish Shaddadid and Rawadid dynasties ruled portions of Aran.

Seljuks and successor states

After the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate, Azerbaijan was ruled by the Iranian Sallarid, Sajid, and Shaddadid dynasties. At the beginning of the 11th century, waves of Oghuz Turks arrived from Central Asia. The first ruling Turkic dynasty was the Ghaznavids, from present-day northern Afghanistan, who took over part of Azerbaijan by 1030. They were followed by the Seljuks, a western branch of the Oghuz, who conquered Iran and the Caucasus pressing on to Iraq and overthrowing the Buyid dynasty in Baghdad in 1055.

Shirvanshahs

Shīrwān Shāh,[8] or Sharwān Shāh,[8] was the title in medieval Islamic Azerbaijan for the ruler of the Shirvan region.[8][need quotation to verify] The Shirvanshahs established a dynasty which ruled Aran and parts of Dagestan,[9] in addition to Shirvan, and was one of the Islamic world's longest-lasting dynasties.

Safavids and the rise of Shia Islam

The Safaviyeh was a Sufi religious order formed during the 1330s by Safi-ad-din Ardabili (1252–1334), for whom it was named. The order converted to the Twelver branch of Shia Islam by the end of the 15th century. Some Safaviyeh, notably the Qizilbash Turks, believed in the mystical and esoteric nature of their rulers and their relationship to the house of Ali and were predisposed to fight for them. The Safavid dynasty claimed to be descended from Ali and his wife, Fatimah (daughter of Muhammad), through the seventh Imam Musa al-Kazim. The Qizilbash increased in number increased by the 16th century; their generals were victorious against the Ak Koyunlu confederation, and captured Tabriz. Safavid Iran, led by Ismail I, expanded its base, sacking Baku in 1501 and persecuting the Shirvanshahs.

From Iranian to Russian rule

The region of Aran had been under Persian empires for millennia; the last one was ruled by the Qajar dynasty. After its defeat by the Russian Empire, Qajar Persia signed the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan ceding Aran, Dagestan and Georgia to Russia.[10][11] Local khanates, such as those in Baku and Ganja, were abolished or accepted Russian rule. 1826–1828 Russo-Persian war began with a Russian defeat but ended with a decisive loss for the Iranian army. The Russian Empire dictated the terms of the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay, in which the Qajars ceded their remaining Caucasian territories.[11] The treaty established the borders of Tsarist Russia and Iran. In the Russian-controlled territories, two provinces were established which later constituted most of the modern republic: Elisavetpol (Ganja) in the west, and Shamakha in the east.

Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

After the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was founded in Tbilisi on May 28, 1918, following an abortive attempt to establish the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic with Armenia and Georgia.[12] The name of "Azerbaijan" which the leading Musavat party adopted, for political reasons,[13][14] was, prior to the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918, exclusively used to identify the adjacent region of contemporary northwestern Iran.[15][16][17] The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was one of the Islamic world's first democratic republics.[18] The ADR extended suffrage to women, making Azerbaijan the first Muslim state in the world to give men and women equal political rights,[12] and established Baku State University.

Architecture

Azerbaijani architecture combines Eastern and Western elements. Many medieval buildings, such as Baku's Maiden Tower and Palace of the Shirvanshahs, are Iranian. Other examples of Iranian influence include the Shaki Khanate palace in Shaki, north-central Azerbaijan; the Surakhany Temple on the Apsheron Peninsula; a number of bridges spanning the Aras, and several mausoleums. Although little monumental architecture was built during the 19th and early 20th centuries, distinctive houses were built in Baku and elsewhere. The Baku Metro is noted for its decor.

19th century

The architecture in what is now is the Republic of Azerbaijan was influenced by the expansion of towns, the application of Russian town-planning principles and the layouts of Baku, Ganja and Shamakhi. After what is now Azerbaijan was ceded to Russia, theatres, schools, hospitals and houses were build during the mid-19th century. The oil industry in what is now Azerbaijan began to influence the regions architecture.[citation needed]

20th century

The first stage of Azerbaijan's architectural development during the Soviet era was related to the construction of the settlements of Binagadi, Rasulzade, Bakikhanov, Montino and Mammadyarov around Baku. Settlements in Absheron Rayon were the first examples of Soviet architecture.

A number of schools were built in Baku and other Azerbaijani cities between 1933 and 1936. Four-story buildings, designed by S.Dadashov and M.Useynov in Baku and other cities, are distinguished by their expressiveness. Classic forms, combined with national architecture traditions, are typical of the projects.

Neft Daşları (also known as the Oil Rocks), a steel-pillar settlement in the open sea, heralded a new era of post-war architecture. Built in connection with the discovery of rich oil fields in the Caspian Sea in 1949, it includes houses, cultural objects and overpasses.

A new period of town-building and architectural development began in Azerbaijan during the 1960s. Baku (the capital) expanded during the decade, and the city's architecture defined its image.

Cinema

Azerbaijan's film industry dates back to 1898 in Baku.[19]

Cuisine

Azerbaijani cuisine,has been influenced by the foods of other cultures. Many foods which are eaten in Azerbaijan appear in the cuisines of other cultures too.

Pomegranate festival

The annual Goychay Pomegranate Festival, usually held in October, features pomegranates from Goychay District, a parade, and Azerbaijani dances and music.[20]

Dance

Azerbaijani dances are melodious. They are danced at formal celebrations, and the dancers wear festive clothes. The dances are fast, and require skill.[21] Azerbaijani clothing is preserved in its national dances.[22]

Examples

- Abayi (Azerbaijani: Abayı) is an Azerbaijani dance originating in Shaki and Zaqatala Rayon. The dance explores middle age; middle-aged people in the region are called Abayi, and the dance is generally performed by middle-aged men and women.[23]

- Agir Karadagi (Azerbaijani: Ağır Qaradağı; "heavy Karadakhi") is a melody for a dance which was created in Karadakh. Popular in Shaki and Zaqatala Rayon, it is played slowly.

- Chichekler ("flowers" in Azeri) is an elegant dance performed by girls in two forms: slow and fast. It was created in 1910. A group of girls collects flowers, forming circles and triangles as they dance. The music is upbeat and energetic.[24]

- Innaby (Azerbaijani: İnnabı; "name of a fruit"), performed by one or two girls, illustrate a young woman's airs and coquettishness.

- Gangi (Azerbaijani: Cəngi; "dagger", martial music) calls the people to unity, friendship and invincibility.[25]

- Lezginka (Azerbaijani: Ləzgi) is a popular Caucasian dance.

- Mirzayi (Azerbaijani: Mirzəyi) is traditionally played at weddings and performed by men and women with handkerchiefs.

- Uzundara (Azerbaijani: Uzundərə; "long valley") is an elegant and lyrical dance performed by women and popular in Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. The song originates in a valley between Aghdam and Prishib (Azerbaijani: Prişib) in Karabakh.

Folk arts

Major elements of Azerbaijani culture are its decorative and applied arts. They are represented by a wide range of handicrafts, such as chasing, jewellery, engraving in metal, carving in wood, stone and bone, carpet-making, pattern-weaving and printing, knitting and embroidery.

Carpets

Baku carpets

Baku carpets are known for the softness of their material, intense colours, and decoration. They have about 10 motifs (including medallions and geometrically-stylized plants) and are exported.

Ganja carpets

Ganja carpets are noted for their ornamental patterns – relatively small in number, between eight and 20 patterns. Gazakh carpets have about 16 patterns. Gazakh District, in northwestern Azerbaijan, is the best-known carpet production region and accounts for the Gazakh and Borchaly carpet groups. Gazakh carpets have a geometric ornamental pattern, with a schematic presentation of plants and animals. Ganja carpets focus on geometric motifs and the schematic presentation of plants and animals.

Karabakh carpets

The Karabakh carpet is named after the Karabakh region (present-day Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent lowland territories).

Shirvan carpets

Shirvan is one of Azerbaijan's oldest regions. Carpet-weaving is widespread among sedentary and nomadic residents. The Shirvan school accounts for carpets manufactured in the following towns and villages: Shemaha, Maraza, Akhsu, and Kurdamir. The school has 25 compositions; Salyan carpets, with similar artistic and technical features, are also included. Shirvan carpets are characterized by intricate designs depicting everyday life, birds, and people.

-

Late-19th-century rug market in Ganja

-

19th-century Gasimushaghi carpet from Şəlvə, Lachin

Novruz, other holidays, and symbols

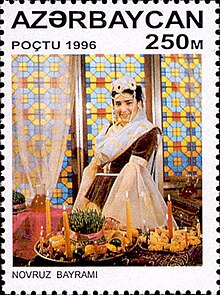

Novruz is a traditional Persian regional holiday, celebrating the New Year and spring, which is observed on the vernal equinox (March 21–22). It symbolizes renewal and fertility.

Festivities, rooted in Zoroastrianism, resemble those in Iran. Preparations begin long before the holiday with housecleaning, tree-planting, dressmaking, egg-painting, and the baking of pastries such as shekerbura, pakhlava and local cuisine. Like other countries which celebrate Novruz, wheat is fried with raisins (kishmish) and nuts (govurga). Wheat sprouts (semeni) are essential. In recognition of fire-worshipping (an ancient Zoroastrian practice), every Tuesday of the four weeks before the holiday children jump over small bonfires and candles are lit (a tradition shared with Iran, where it is known as Chahar-shanbeh sori). On Novruz eve, the graves of relatives are visited and tended.[26] That evening, the family gathers around the holiday table laid with Novruz dishes. The holiday lasts for several days, ending with dancing, music and sports.

During the Soviet era, the celebration of Novruz was unofficial and sometimes prohibited.[27] Since Azerbaijani independence, Novruz has been a public holiday. Each Tuesday of the preceding four weeks is devoted to one of the four elements: water, fire, earth and wind.[28][29]

Other public and traditional holidays include Ramadan, Women's Day, Ramazan Bayrami, Gurban Bayrami, Republic Day, Constitution Day, Victory Day, Armed Forces Day, Salvation Day, and Flag Day.[30] In rural areas, harvests are celebrated. Commemorative and remembrance days include Black January, the commemoration of the Khojaly massacre, and the March Days.

Symbols include the eight-pointed star combined with the fire element in the national emblem. The country's flag dates to the late Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. "Azərbaycan marşı", its national anthem, was written by Ahmad Javad with music by Uzeyir Hajibeyov.

Literature

Azerbaijani literature is written in Azerbaijani, Azerbaijan's state language. Its closest relatives are Turkish and Turkmen. Azeri, is split up into two distinct languages[31]. North Azerbaijani (based on the Shirvan dialect and spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan[32]) and South Azerbaijani (based on the Tabriz dialect and spoken in Iranian Azerbaijan[33]) Both sublanguages are Oghuz languages (a sub-branch of the Turkic languages) and are mutually intelligible with other Oghuz dialects spoken in Turkey, Iran, Turkmenistan, Georgia, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Russia, the Balkans and the Middle East.

The language arrived with the invasion and settlement of waves of Turkic tribes from Central Asia over several centuries. The indigenous language of the region around the Aras was a mixture of Iranian Tati, Talyshi, and Armenian; Talyshi is still spoken in parts of Azerbaijan. With the increasing dominance of Turkic rulers, the region's language was gradually infused with Turkic. As a result of the Soviet Union's language policy, Russian is widely spoken as a second language.

Classical era

The Book of Dede Korkut (which may date to the 9th century CE[34] and was first transcribed by the 14th century),[34] Alpamysh and Koroghlu are Turkic epics that are widely spread among North and South Azerbaiajnis and enjoy high popularity among them.[35][36] The earliest known figure in Azeri literature is Izzeddin Hasanoghlu, who composed a diwan of Persian and Ajemi Turkic ghazals.[37][38] He used his own name for the Persian ghazals, and the pen name Hasan Oghlu for his Turkic poems.[37] Nizami Ganjavi (born in Ganja) is considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature, bringing a colloquial, realistic style to the Persian epic.[39][40]

During the 14th century, what comprises the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan was ruled by the Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkic tribal confederacies. Poets of this period included Kadi Burhan al-Din, Haqiqi (the pen name of Jahan Shah), and Habibi.[41] The end of the century was the beginning of the literary activity of Imadaddin Nasimi,[42] one of the greatest Turkic[43][44][45] Hurufi poets[46] and a prominent early diwan master[46] who also wrote in Persian[44][47] and Arabic.[46]

Soviet era

Under Soviet rule, particularly under Joseph Stalin, Azeri writers who did not conform to the Communist Party line were persecuted. Bolsheviks sought to destroy the nationalist, intellectual elite who had become established during the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and, during the 1930s, many writers and intellectuals became mouthpieces for Soviet propaganda.

Influences

Persian and Arabic literature have influenced Azeri literature, especially during its classical era. Influential Persian poets include Ferdowsi, Sanai, Hafez, Saadi Shirazi, Attar of Nishapur, and Rumi. The Quran and Hadith have also influenced Azeri literature. Arabic poets include Al-Hallaj who has influenced Sufi literature.

Journalism

In 1875, Akinchi (Əkinçi / اکينچی ), The Cultivator) was the first Azeri newspaper published in the Russian Empire. It was founded by Hasan bey Zardabi, a journalist and education advocate.[48] A 2015 Washington Post editorial noted that a number of Azerbaijani journalists, bloggers, lawyers, and human-rights activists have been subjected to lengthy pretrial detention for their criticism of President Ilham Aliyev and other government authorities.[49]

Music

Azerbaijani music is influenced by the music of Iran, the Caucasus and Central Asia, and resembles Iranian and Turkish music.[50]

Mugham

Azerbaijani classical music of Azerbaijan, known as mugham (accurately spelt muğam), is usually a suite with poetry and instrumental interludes. The sung poetry sometimes includes a form of throat singing similar to yodelling. Typically about divine love, the poetry is most often linked to Sufism.

Unlike Central Asian mugham, the Azeri form is less rigid (comparable to improvised jazz).[51] UNESCO proclaimed Azerbaijani mugham a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 7 November 2003.[52] New York Times music critic Jon Pareles called Mugham singer Alim Qasimov "one of the greatest singers alive".[53]

An annual Mugham Festival is held in Shaki. Held in Shusha until 1988, it was moved to Shaki in November 1994 because of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Meykhana

Meykhana is an Azerbaijani literary and folk rap tradition[54] consisting of an unaccompanied song performed by one or more people who improvise on a subject. Its name derives from the Turkish meyhane (tavern, pub), which originated from the Persian words mey (wine) and hane (house).[55]

Instruments

Instruments that are used in Azerbaijan, for Azerbaijani music include fourteen string instruments, eight percussion instruments and six wind instruments.[56] Traditional stringed instruments include the tar (skin-faced lute), kamancha (skin-faced spike fiddle), oud (originally barbat), and saz (long-necked lute). The balaban is a double-reed wind instrument, and percussion instruments include the ghaval and daf frame drums; the cylindrical, double-faced naghara, and the larger davul. Other instruments include the garmon (a small accordion) and tutek (whistle flute).

Ashiqs

Ashiqs are traveling bards who sing and play the saz, a type of lute. Their songs are partially improvised around a common base. The Ashiq tradition in the Turkic cultures of Anatolia, Azerbaijan and Central Asia has its origins in ancient shamanism.[57]

Religion

About 93 percent of Azerbaijan's population is nominally Muslim, and approximately five percent of the population belong to the Russian Orthodox Church. Muslim religious observance is relatively low, and Muslim identity tends to be based more on culture and ethnicity than on religion. The Muslim population is approximately 70 percent Shia and 30 percent Sunni, with differences not defined sharply. Fairly-large expatriate Christian and Muslim communities exist in Baku, the capital, and are generally permitted to worship freely.

Islam

Christianity

About 3.1% to 4.8% of Azerbaijan's population is nominally Christians, an estimate of between 280,000 and 450,000.[58] Orthodoxy is represented in Azerbaijan by the Russian and Georgian Orthodox Churches. The Russian Orthodox churches are part of the Eparchy of Baku and the Caspian Region. The Catholic Church in Azerbaijan, under the spiritual leadership of the pope in Rome, has 400 adherents; about half are foreign diplomats or work for oil companies.[59]

Judaism

Azerbaijan has three communities of Jews (Mountain Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Georgian Jews), with a combined population of almost 16,000. Eleven thousand are Mountain Jews, with 6,000 in Baku and 4,000 in Guba; 4,300 are Ashkenazi Jews (most of whom live in Baku and Sumgayit), and 700 are Georgian Jews.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism in Azerbaijan dates back to the first millennium BC. With the rest of the Persian Empire, it remained a predominantly-Zoroastrian state until the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century AD. Azerbaijan means "Land of Eternal Fire" in Middle Persian, indicating a link with Zoroastrianism.[60] Traces of the religion are still visible in Atashgah, Ramana, Khinalyg, and Yanar Dag.

Cultural reforms

After independence, Azerbaijan has taken measures to protect its cultural values, enhance its cultural life and cooperate with international organizations in this area. Legislation has been adopted by the Azerbaijani Parliament in the realm of culture, including:[61] restoration of the Azerbaijani alphabet based on Latin script (25 December 1991); mass media (21 July 1992); copyright (10 September 1993); advertising (3 October 1997); culture (6 February 1998); protection of historical and cultural monuments (10 April 1998); grants (17 April 1998); freedom of information (19 June 1998); cinematography (3 July 1998); sculpture (3 July 1998); tourism (4 July 1999); urban planning (11 June 1999); National Archive Fund (22 June 1999); mass media (8 February 2000); museums (24 March 2000), and publishing.[61] Legal protection of historical and cultural monuments is also outlined in international documents, including the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.[61]

The Ministry of Culture and Tourism was established in a 2006 decree by President Ilham Aliyev. In addition to preserving the national culture internally, Azerbaijan cooperates with international organizations such as the UN, UNESCO, the Islamic World Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (ISESCO) and the Council of Europe to formulate an international cultural policy[62] and participates in international projects.[61]

Azerbaijan joined the European Heritage Days project, initiated by the Council of Europe and the European Union, in 2000. The European Heritage Days – 2003 Campaign was hosted in Azerbaijan from 26 to 28 September of that year. The campaign planned to open restored monuments, review monuments being restored, exhibit and catalogue the 2003 International Photo Initiative, and conduct the European Common Heritage Program and European Cultural Heritage Campaign at schools and universities.[61]

The topic of the 2005 European Heritage Days, held in Azerbaijan, was "Civilizations and peacekeeping processes". It had two events: the East-West Baku International Festival and a youth photo contest and exhibition.[61]

Azerbaijan became the member of UNESCO in 1992, and the UNESCO National Commission in Azerbaijan (within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) was established by decree of President Heydar Aliyev in 1994. Azerbaijan joined UNESCO conventions on the preservation of cultural values and heritage, the recognition of specialities in higher education, diplomas and degrees, and the preservation of intangible cultural heritage.[62]

Baku's Old City (with the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and Maiden Tower) was included on the World Heritage List in 2000, and Gobustan National Park in 2007.[63] Mugham was declared a masterpiece of humankind and intangible heritage in 2003, and the art of Azerbaijani Ashiq, Novruz, Azerbaijani carpet weaving, craftsmanship and performance of the Tar, Chovgan, Kelaghayi, the copper craftsmanship of Lahij and flatbread making and sharing have been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[63]

Concerts, jubilees, seminars and symposiums, conferences and congresses, meetings and festivities were organized within the framework of UNESCO[62] to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the birth of Fuzuli (1996), the 1300th anniversary of the Book of Dede Korkut (2000), the 800th anniversary of the birth of Nasraddin Tusi (2001), the 200th anniversary of the birth of Mirza Kazimbey (2002), the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mir Jalal Pashayev (2008), the 900th anniversary of the achievements of Mahsati (2013), and the 100th anniversary of Uzeyir Hajibeyli's musical comedy Arshin Mal Alan (2013).[64] In 2013, UNESCO and Azerbaijan signed a framework agreement on cooperation in the fields of education, science, culture and communications.[65]

Baku was declared the 2009 capital of Islamic culture when it hosted the sixth Islamic Conference of Culture Ministers.[66] The city hosted the World Forum on Intercultural Dialogue in 2011, 2013, 2015 and 2017,[67] supported by UNESCO, the UN Alliance of Civilizations, the North-South Center of the Council of Europe, ISESCO and Euronews.[68]

See also

- Ashik Kerib

- Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan

- Women in Azerbaijan

- Azerbaijani fairy tales

- Azerbaijani-Mongolian cultural relations

- Azerbaijani calendar beliefs

- Azerbaijani nomadic life

Notes

- ^ The name used for the region north of the Aras from before the arrival of the Arabs to the Qajar period.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Azerbaijan - US Library of Congress Country Studies (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ James Stuart Olson. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 978-0-313-27497-8

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "The list of provinces given in the inscription of Ka'be-ye Zardusht defines the extent of the empire under Shapur, in clockwise geographic enumeration: (1) Persis (Fars), (2) Parthia, (3) Susiana (Khuzestan), (4) Maishan (Mesene), (5) Asuristan (southern Mesopotamia), (6) Adiabene, (7) Arabistan (northern Mesopotamia), (8) Atropatene (Azerbaijan), (9) Armenia, (10) Iberia (Georgia), (11) Machelonia, (12) Albania (eastern Caucasus), (13) Balasagan up to the Caucasus Mountains and the Gate of Albania (also known as Gate of the Alans), (14) Patishkhwagar (all of the Elburz Mountains), (15) Media, (16) Hyrcania (Gorgan), (17) Margiana (Merv), (18) Aria, (19) Abarshahr, (20) Carmania (Kerman), (21) Sakastan (Sistan), (22) Turan, (23) Mokran (Makran), (24) Paratan (Paradene), (25) India (probably restricted to the Indus River delta area), (26) Kushanshahr, until as far as Peshawar and until Kashgar and (the borders of) Sogdiana and Tashkent, and (27), on the farther side of the sea, Mazun (Oman)."

- ^ "Albania" Archived 2009-01-20 at the Wayback Machine - Encyclopedia Iranica, p. 807 (retrieved 15 June 2006).

- ^ "Voices of the Ancients: Heyerdahl Intrigued by Rare Caucasus Albanian Text" by Dr. Zaza Alexidze Archived 2009-01-17 at the Wayback Machine - Azerbaijan International, Summer 2002 (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ "Islamic Conquest."

- ^ A History of Islamic Societies by Ira Lapidus, p. 48. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1988), ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3 (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ a b c Barthold, W., C.E. Bosworth "Shirwan Shah, Sharwan Shah. "Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2nd edition

- ^ Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition, Columbia University, 1995, p. 2, ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3: "In the fifteenth century this dynasty of Shirvanshahs flourished north of the Araxes."

- ^ Frankopan, Peter (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-4088-3998-0.

To many, the fact that Ouseley—who had made such efforts to cultivate the Shah—drafted the humiliating Treaty of Gulistan in 1813 following the Russo-Persian War which awarded most of the western flank of the Caspian, including Dagestan, Mingrelia, Abkhazia, Derbent and Baku, to Russia, seemed nothing less than an act of betrayal.

- ^ a b Shafiyev, Farid (2018). "Russian Conquest of the South Caucasus". Resettling the Borderlands: State Relocations and Ethnic Conflict in the South Caucasus. Montreal, Kingston, London, Chicago: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 16–42. ISBN 978-0-7735-5372-9.

- ^ a b Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia: 1917-1921. The New York Philosophical Library. pp. 124, 222, 229, 269–270. ISBN 978-0-8305-0076-5.

- ^ Yilmaz, Harun (2015). National Identities in Soviet Historiography: The Rise of Nations Under Stalin. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-317-59664-6.

On May 27, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (DRA) was declared with Ottoman military support. The rulers of the DRA refused to identify themselves as [Transcaucasian] Tatar, which they rightfully considered to be a Russian colonial definition. (...) Neighboring Iran did not welcome did not welcome the DRA's adoptation of the name of "Azerbaijan" for the country because it could also refer to Iranian Azerbaijan and implied a territorial claim.

- ^ Barthold, Vasily (1963). Sochineniya, vol II/1. Moscow. p. 706.

(...) whenever it is necessary to choose a name that will encompass all regions of the republic of Azerbaijan, name Arran can be chosen. But the term Azerbaijan was chosen because when the Azerbaijan republic was created, it was assumed that this and the Persian Azerbaijan will be one entity, because the population of both has a big similarity. On this basis, the word Azerbaijan was chosen. Of course right now when the word Azerbaijan is used, it has two meanings as Persian Azerbaijan and as a republic, its confusing and a question rises as to which Azerbaijan is talked about.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-86064-554-9.

- ^ Dekmejian, R. Hrair; Simonian, Hovann H. (2003). Troubled Waters: The Geopolitics of the Caspian Region. I.B. Tauris. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-86064-922-6.

Until 1918, when the Musavat regime decided to name the newly independent state Azerbaijan, this designation had been used exclusively to identify the Iranian province of Azerbaijan.

- ^ Rezvani, Babak (2014). Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan: academisch proefschrift. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-90-485-1928-6.

The region to the north of the river Araxes was not called Azerbaijan prior to 1918, unlike the region in northwestern Iran that has been called since so long ago.

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3, ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3 and Reinhard Schulze. A Modern History of the Islamic World. I.B.Tauris, 2000. ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9, ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9. Citations are at Talk:Azerbaijan Democratic Republic#First or second

- ^ Aydin Kazimzade (Autumn 1997). "Celebrating 100 Years in Film, not 80". Azerbaijan International. 5 (1): 30–35. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020.

- ^ Iguide.travel Goychay Activities: Pomegranate Festival

- ^ "Culture of Azerbaijan - The Arts and Humanities". Everyculture.com. 1918-05-28. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Azerbaijan - a part of Europe (2007-11-24). "Azerbaijan - a part of Europe". Azeriyoungsters.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Azerbaijani Dance Archived May 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Traditional Azeri Dance". Bangkokcompanies.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ "Embassy of Azerbaijan; National dances". Azerembsof.com. 31 May 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Azerbaijani traditions". Everyculture.com. 1918-05-28. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Waters, Zena (April–May 2005), "What exactly is Novruz Bayram", Azerbaijan Today, no. 12, archived from the original on 2011-05-14, retrieved 2009-03-22

- ^ "International Day of Nowruz- 21 March". Azerembassy-kuwait.org. 2010-03-17. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ^ "Azerbaijan marks Novruz holiday". En.trend.az. 2010-03-20. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ^ "Azerbaijan sets National Flag Day". Today.az. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Salehi, Mohammad; Neysani, Aydin (2017). "Receptive intelligibility of Turkish to Iranian-Azerbaijani speakers". Cogent Education. 4 (1): 3. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2017.1326653. S2CID121180361.

Northern and Southern Azerbaijani are considered distinct languages by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (...)

- ^ "Azerbaijani, North". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Azerbaijani, South". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Birchwood, Matthew; Dimmock, Matthew (2005). Cultural Encounters Between East and West, 1453-1699. Cambridge Scholars Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-904303-41-1.

- ^ Prof. Paksoy H.B. "Alpamysh. Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule". Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research Monograph Series, Hartford, Connecticut, First AACAR Edition, 1989, ISBN 0-9621379-9-5, ISBN 0-9621379-0-1 (pbk.), p. 1

- ^ Karl Reichl Singing the Past: Turkic and Medieval Heroic Poetry, Cornell University Press. 2000. "The central traditions find their continuation in a fourth group, the epic poetry of the southwestern Turkic peoples, the Turkmens, Azerbaijanis, and Anatolian Turks. Here the predomination form is prosimetric, and there is a predilection, for love and adventure romance. The main hero of their adventure romances is Koroghlu.

- ^ a b Beale, Thomas William; Keene, Henry George (1894). An Oriental Biographical Dictionary. W. H. Allen. p. 311.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ A. Caferoglu, "Adhari(azeri)", in Encyclopedia of Islam, (new edition), Vol. 1, (Leiden, 1986)

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Nezami"

- ^ Dr. Julie Scott Meisami, "The Haft Paykar: A Medieval Persian Romance (Oxford World's Classics)", Oxford University Press (T), 1995, ISBN 978-0-19-283184-2, extract

- ^ Tyrrell, Maliheh S. (2001). Aesopian Literary Dimensions of Azerbaijani Literature of the Soviet Period, 1920-1990. Lexington Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7391-0169-8.

- ^ Průšek, Jaroslav (1974). Dictionary of Oriental Literatures. Basic Books. p. 138.

- ^ Baldick, Julian (2000). Mystical Islam: An Introduction to Sufism. I. B. Tauris. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-86064-631-7.

- ^ a b Burrill, Kathleen R.F. (1972). The Quatrains of Nesimi Fourteenth-Century Turkic Hurufi. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. ISBN 978-90-279-2328-8.

- ^ Lambton, Ann K. S.; Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lewis, Bernard (1970). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 689. ISBN 978-0-521-29138-5.

- ^ a b c Seyid Imadeddin Nesimi. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ Babinger, Franz (2008). "Nesīmī, Seyyid ʿImād al-Dīn". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Online. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ "Welcome to AATT - Affiliates". Princeton.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Jailed without trial in Azerbaijan". The Washington Post. 1 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Almaty or Bust Archived July 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Sultanova and Broughton, pg. 25

- ^ "EurasiaNet Civil Society - The Baku Jazz Festival: Reviving a Tradition in Azerbaijan". Eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ "Azerbaijani Mugham". UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (15 March 2010). "Classical Azeri Poetry in Song, From a Team of Father and Daughter". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Bahl, Taru; Syed, M. H. (2003). Encyclopaedia of the Muslim World. Anmol Publications PVT. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-261-1419-1.

- ^ Zubaida, Sami; Tapper, Richard (1994). Culinary Cultures of the Middle East. IB Tauris in association with Centre of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-85043-742-0.

- ^ "The Azerbaijan musical instruments". Atlas.musigi-dunya.az. Archived from the original on 2007-08-26. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ IUE.it - European University Institute, Florence, Italy (retrieved 10 August 2006).

- ^ "Global Christianity An Interactive Feature". Archived from the original on 2014-07-19. Retrieved 2022-01-23.

- ^ (in Russian) Construction of Catholic Church in Baku Coming to End Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine by R. Manafli. Echo. 8 March 2007

- ^ "Hankooki.com". Times.hankooki.com. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ a b c d e f "Social and cultural issues". Mfa.gov.az (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ a b c Aliyeva, Sevdagul (2011). "Chapter 4: Tourism Development, Culture and Cultural Identity, Cross-Cultural Relationships". 6 Silk Road International Conference "Globalization and Security in Black and Caspian Seas Regions" (PDF). pp. 232–236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-12. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ a b National Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for UNESCO. "Cooperation in the field of culture". Unesco.az. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ National Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for UNESCO. "The list of anniversaries celebrated in the framework of the UNESCO programme on anniversaries of great personalities and historic events". Unesco.az. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ National Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for UNESCO. "Framework Agreement". Unesco.az. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "Capitals of Islamic Culture | Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – ISESCO –". Isesco.org.ma. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "Introduction – Baku process". Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "About Process – Baku process". bakuprocess.az. Archived from the original on 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2017-08-15.