Leatherhead

| Leatherhead | |

|---|---|

2 Bridge Street, Leatherhead | |

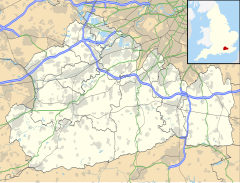

Location within Surrey | |

| Area | 12.54 km2 (4.84 sq mi) |

| Population | 11,316 (2011 census)[1] or 32,522 as to its Built-up Area which extends to Effingham[2] |

| • Density | 902/km2 (2,340/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ1656 |

| • London | 17 mi (27 km) north |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Leatherhead |

| Postcode district | KT22 |

| Dialling code | 01372 |

| Police | Surrey |

| Fire | Surrey |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

Leatherhead is a town in the Mole Valley district of Surrey, England, about 17 mi (27 km) south of Central London. The settlement grew up beside a ford on the River Mole, from which its name is thought to derive. During the late Anglo-Saxon period, Leatherhead was a royal vill and is first mentioned in the will of Alfred the Great in 880 AD. The first bridge across the Mole may have been constructed in around 1200 and this may have coincided with the expansion of the town and the enlargement of the parish church.

For much of its history, Leatherhead was primarily an agricultural settlement, with a weekly market being held until the mid-Elizabethan era. The construction of turnpike roads in the mid-18th century and the arrival of the railways in the second half of the 19th century attracted newcomers and began to stimulate the local economy. Large-scale manufacturing industries arrived following the end of the First World War and companies with factories in the town included Ronson and Goblin Vacuum Cleaners. Several organisations working with disabled people also opened treatment and training facilities, including The Royal School for the Blind, Queen Elizabeth's Foundation and the Ex-services Welfare Society.

Towards the end of the 20th century, manufacturing in Leatherhead had begun to decline and the town was instead starting to attract service sector employers. The former industrial areas were converted to business parks, which attracted multinational companies, including Esso and Unilever. A controversial redevelopment took place in the town centre in the early 1980s, which included the construction of the Swan Centre. The work, which also included the pedestrianisation of the main shopping area, was widely blamed for a decline in the local retail economy. In 2002, the BBC identified Leatherhead as having one of the worst High Streets in England, but in 2007, the local press described the town centre as "bustling".

Toponymy

The origins and meaning of the name 'Leatherhead' are uncertain.[4] Early spellings include Leodridan (880),[5] Leret (1086),[6] Lereda (1156), Ledreda (1160) and Leddrede (1195).[7]

The name is usually thought to derive from the Brythonic lēod-rida, meaning 'a public ford'.[8] Richard Coates has suggested a derivation from the Brythonic lēd-rïd (as in the modern Welsh "llwyd rhyd") meaning 'grey ford'. The Anglo-Saxon and English forms are a distortion of the original British name.[4][9][10]

Geography

Location and topography

Leatherhead is a town in central Surrey, around 17 mi (27 km) south of the centre of London. It lies on the southern edge of the London Basin and the highest point in the parish, at Leatherhead Downs, is 135 m (443 ft) above ordnance datum. The High Street runs roughly west to east and was part of the Guildford to Epsom road, which crossed the River Mole at the Town Bridge.[5][11] The Mole, which passes to the west of the centre, has cut a steep-sided valley through the North Downs, south of the town.[12][n 2]

Geology

Leatherhead is at the southern edge of the London Basin, where the permeable upper chalk of the North Downs dips beneath the impermeable London Clay.[18] The difference in properties between the two formations results in a high water table and springs are found at regular intervals along the boundary between them. Several settlements were established along this spring line in Anglo-Saxon and early medieval times, including the villages of Ashtead, Fetcham and Effingham, which are linked to Leatherhead by the Guildford to Epsom road.[18]

History

Early history

The earliest evidence of human activity in Leatherhead comes from the Iron Age. Flints, a probable well and two pits were discovered in 2012 during building work on Garlands Road and the finds suggest that the site was also used in the early Roman period.[19][n 3] Traces of Iron Age field systems and settlement activity have been observed at Hawks Hill, Fetcham (about 1 km (0.62 mi) southwest of the town centre)[21] and on Mickleham Downs (about 3 km (2 mi) to the south).[22][23] Also to the south, the Druid's Grove at Norbury Park may have been used for pre-Christian pagan gatherings.[24]

An Anglo-Saxon settlement at Leatherhead was most likely founded on the east side of the River Mole in the second half of the 6th century. A burial ground, dating to the same period, has been identified on the west side at Hawks Hill.[25][26] A second cemetery was discovered in 1984 on the site of the former Goblin factory in Ermyn Way (now the location of the offices of Esso). Excavations uncovered the remains of at least 40 individuals and the artefacts found, including knives, buckles and necklaces, suggest that they were pagan burials.[27][28]

From the mid-9th century, Leatherhead was the centre of a royal vill, which encompassed Ashtead, Fetcham and Bookham.[29] The first known reference to the settlement is in the will of Alfred the Great in 880, in which land at Leodridan was bequeathed to his son, Edward the Elder.[5] By the 10th century, there was a minster church in Leatherhead, and the town was administered as part of the Copthorne Hundred.[25][29]

Governance

The medieval history of Leatherhead is complex, since the parish was divided into a number of manors.[5] The town appears in Domesday Book of 1086 as Leret and was held by Osbern de Ow as a mesne lord to William I. Its Domesday assets were one church, belonging to Ewell, and 40 acres (160,000 m2) of land. It was valued at an annual income of £1.[6][30] To the south was the manor of Thorncroft, which was held by Richard son of Gilbert as tenant-in-chief.[31] To the north was the manor of Pachesham, subdivided into two parts, each of which was held by a mesne lord to the tenant-in-chief, Bishop Odo of Bayeux.[6][32] Finally there are sporadic mentions in surviving documents of a manor called "Minchin", which may have belonged to Kilburn Priory in Middlesex.[33][34]

For the majority of its history, Thorncroft Manor appears to have remained as a single, intact entity, with the exception of the subinfeudation of Bocketts Farm, which took place before 1300.[35][36] In 1086, the manor was held by Richard fitz Gilbert and it passed through his family (the Clares) to his granddaughter, Margaret de Clare, who married into the de Montfitchet family of Essex. Her great-grandson, Richard de Montfichet, sold the manor to John de Cheresbure in around 1190 and it was next purchased by Philip Basset and his second wife, Ela, Countess of Warwick in around 1255.[35] In 1266, they granted Thorncroft (which provided an income of £20 per year) to Walter de Merton, who used it to endow the college in Oxford that he had founded in 1264.[37] Merton College remained the lords of the manor until 1904[38] and the continuity of ownership ensured that an almost complete set of manorial rolls from 1278 onwards has been preserved.[39] In 1497, Richard FitzJames, the Warden of the College, authorised the expenditure of £37 for a new manor house, which was used until the Georgian era.[38]

In contrast, the manor of Pachesham became fragmented as the Middle Ages progressed. By the time of Domesday book, it was already divided into two parts, the smaller of which was later referred to as "Pachenesham Parva". No written record of either part of the manor survives from the subsequent 200 years, but in 1286 land belongong to Pachesham was recorded as passing to Eustace de Hacche. De Haache rebuilt the manor house in around 1293, which he enclosed with a moat.[40] Excavations of the manor house site (now known as The Mounts) in the mid-20th century provided evidence of several medieval buildings, including a hall, a chapel and a probable stable block.[41] The value of the manor appears to have declined in the mid-14th century and, in 1386, it was let to William Wimbledon for an annual sum of £20. In 1393, one year after a serious fire had destroyed much of Leatherhead, Wimbledon defaulted on the rent and was accused of dismantling several of the manor buildings. From the start of the 15th century, the land was divided between twelve lessees and the manor then disappears from the historical record.[42]

Surviving records of Pachenesham Parva from around 1330 suggest that it covered an area of 46 ha (114 acres) on the east bank of the River Mole, to the north west of the town centre.[43] The manor appears to have remained intact through the Middle Ages and land was added to the estate as the remainder of Pachesham was broken up. By the early 17th century, the area was known as Randalls Farm and, in 1805, the associated land totalled 182 ha (450 acres).[44]

Reforms during the Tudor period replaced the day-to-day administration of towns such as Leatherhead in the hands of the vestry of the parish church.[45][46] The vestry was charged with appointing a parish constable, maintaining a lock-up and organising a basic fire service. Until 1834, it also administered poor relief and was responsible for building a workhouse on Kingston Road in 1808.[46][47]

During the 19th century, local government reforms gradually removed the duties of running of the town's infrastructure and services from the vestry. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 placed the workhouse in the care of a board of guardians at Epsom[48] and the Local Government Act 1888 transferred many administrative responsibilities to the newly formed Surrey County Council. The Leatherhead Urban District Council (UDC) was formed six years later[49] and in 1903 the county council was placed in charge of the town's National schools.[50] The Local Government Act 1972 created Mole Valley District Council, by combining the UDCs of Leatherhead and Dorking with the majority of the Dorking and Horley Rural District.[51]

Transport and communications

Leatherhead developed at a crossing point of the River Mole at the intersection between the north–south Kingston–Dorking and east–west Epsom–Guildford roads. The original position of the ford is unclear, but it may have been around 90 m (100 yd) upstream of the present Leatherhead Bridge at a point where a continuation of Elm Road would meet the river.[29]

The first indication of a bridge at Leatherhead is a local deed dated to 1250, which was witnessed by a "Simon of the Bridge". Later that century, in around 1286, a Peter Dryaw of Fetcham is recorded as mortgaging the annual rent of a house "at the bridge in the town of Ledderede" to Merton College, Oxford.[52] It is possible that the construction of the first bridge coincided with an expansion of the town and the enlargement of the parish church, which took place around 1200.[53]

It is not clear to what extent the Mole was used for navigation in the past, but in the early Middle Ages, it is likely that shallow-bottomed craft were able to reach Leatherhead from the Thames for much of the year. In the late 13th century, Thorncroft Manor purchased a shout, a type of boat up to 16 metres (52 ft) in length, used to transport produce to market.[54] Several schemes were proposed to make the Mole navigable in the 17th and 18th centuries, but none were enacted.[55][56]

The turnpike road between Epsom and Horsham, which ran through Leatherhead, was authorised by Parliament in 1755.[57] Turnpikes to Guildford and Kingston were opened in 1758 and 1811 respectively[58] and one of the tollhouses was sited near to the present Leatherhead Institute.[59] Stagecoaches, which had begun to run through Leatherhead to London in the 1680s,[60] increased in frequency after the building of the turnpikes. By 1838 there were daily coaches to Arundel, Bognor and Worthing,[61] which typically stopped at the Swan Inn in the High Street.[62][n 4] With the arrival of the railway at Epsom in 1847, the long-distance coaches were discontinued and horse-drawn omnibuses took over local journeys.[62]

The first railway to arrive in Leatherhead was built by the Epsom and Leatherhead Railway Company. The line, which terminated at a station in Kingston Road, opened on 1 February 1859. Initially all trains were operated by the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) and, for the first two months, only ran as far as Epsom.[66] The completion of the line through Worcester Park enabled these services to be extended to London Waterloo from April of the same year and, in August 1859, the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR) began to run trains from Leatherhead to London Bridge.[67]

The Mole Gap through the North Downs had been identified as a potential railway corridor as early as the 1830s, but the line south from Leatherhead to Dorking was not opened until 1867.[68] The Kingston Road station, which had been laid out as a terminus, was closed and two new adjacent stations (either side of the present Station Approach) were opened. The LBSCR station, which was closer to the town centre, was initially the only one connected to the line to Dorking. It was designed by C. H. Driver in a fine Gothic Revival style and is the station that survives today.[67][69] The LSWR built its station as a terminus, but its line was extended westwards to Bookham in 1885. The two railway companies were amalgamated in 1923, when the Southern Railway was formed.[70] All railway lines through Leatherhead were electrified in 1925 and the LSWR station was closed in 1927. In the late 1930s, a southward extension of the Chessington branch line was proposed, but the creation of the Metropolitan Green Belt prevented the scheme from being enacted.[70]

The construction of the A24 bypass (between Givons Grove and Leatherhead Common) started in 1931[71] and the final section opened in May 1934.[72] Young Street (the A246 between Bocketts Farm and Givons Grove) was built by the Corps of Royal Canadian Military Engineers between June 1940 and May 1941.[73] In October 1985, the town was joined to the UK motorway system when the M25 was opened between Wisley and Reigate.[74]

Commerce

The right to hold a weekly market and an annual fair was granted to Leatherhead in 1248 by Henry III.[5] The market place is thought to have been at the junction of Bridge Street, North Street and High Street and the town stocks were probably in the same area.[63] The market appears to have ended in the mid-Elizabethan era, however the annual fair continued and in the late 17th century was held on 8 September, the feast of the Nativity of Mary.[75]

The construction of the turnpikes, and later the railways, attracted wealthier residents to Leatherhead. Many of these incomers had accumulated their wealth as entrepreneurs in London and had no previous connection to the area. By the start of the Victorian era, they were beginning to influence the local economy. Small, family-based manufacturing firms began to grow, engaged in industries such as brick-making, milling of logs, tanning, shoemaking, malting and brewing. In the 1841 census, 18.5% of the town's inhabitants were employed in agriculture-related trades, but forty years later, the proportion had fallen to 5.4%.[76]

Larger-scale industries arrived in Leatherhead in the first half of the 20th century. In 1928, the Rayon manufacturing company opened a factory in Ermyn Way, close to the border with Ashtead parish[77] and was replaced ten years later by the manufacturing plant for Goblin Vacuum Cleaners.[78] Also in the 1930s, a silk-making farm and electrical cable factory were established in the town.[78][79] Following the end of the Second World War, Ronson, the US-based manufacturer of cigarette lighters, opened a manufacturing plant at Dorincourt, to the north of the town.[80][81] The factory moved to Randalls Road in 1953, but it closed in 1981 when the company went into liquidation. A business park opened in its place.[81][82][n 5]

The Ex-services Welfare Society purchased Long House on Ermin Way following the end of the First World War. The charity constructed a factory in the grounds to provide employment for disabled veterans, producing electrical items, such as electric blankets. In 1933, the organisation opened a treatment centre at Tyrwhitt House in Oaklawn Road, named after Reginald Tyrwhitt, its president at the time. In 1981, the factory was purchased by Remploy. It continued to manufacture electrical goods, but under the new ownership, its operations expanded to include the assembly and packaging of mechanical equipment.[84] The Remploy factory closed in 2007, with the loss of 43 jobs.[85][86] The Ex-services Welfare Society, now known as Combat Stress,[84] continues to operate its treatment centre at Tyrwhitt House in north Leatherhead.[87]

Large-scale manufacturing in Leatherhead was short lived and, as the 20th century progressed, the town started to attract service sector industries. Among the research institutes formerly based in the town, Leatherhead Food Research was founded in 1919[88] and the Central Electricity Research Laboratories (CERL) opened in 1950.[89][90] Both organisations left the town in the early 2000s.[91] The Ronson and Goblin factories closed in the early 1980s and their sites were redeveloped, in the latter case for the UK headquarters of Esso.[80] The UK head offices of Unilever (on the site of the former CERL) and Hyundai were opened in Leatherhead in 2008 and 2020 respectively.[92][93]

A controversial redevelopment of the road network in the town centre took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The project began with the demolition of the Prince of Wales pub in 1979 and the Swan Centre, a covered shopping centre with a multistorey car park, was constructed in its place. At the same time a one-way system was created and the High Street was pedestrianised.[94] By September 1981, the scheme was already attracting criticism from local traders and residents, who blamed the traffic alterations for a steep decline in footfall.[95] In January 1983, the County Planning Officer admitted that the "complexity of present routes undoubtedly detracts from the appeal of the town to car-borne shoppers."[96] In 2002, BBC News named Leatherhead as having one of the worst High Streets in the country.[97][98] Five years later, in 2007, the local press reported that the town was "bustling with people, and packed full with an abundance of shops, entertainment facilities and job opportunities." The revival in fortunes was attributed to a variety of community initiatives, including a new drama festival.[99]

Residential development

Leatherhead began to expand at the start of the 20th century and the population grew from in 4,694 in 1901 to 5,491 in 1911.[100] New housing developments were built between 1900 and 1905 in Fairfield, Highlands and Kingston Roads, and Queen Anne's Garden. Later in the decade, houses were constructed in Copthorne, Clinton, Reigate and Woodville Roads, Kingston Avenue and St Nicholas Hill.[101]

The first council housing in the town, a development of 59 houses in Poplar Road, was built by Leatherhead UDC in 1921. Preference for rehousing was given to ex-servicemen and their families. In 1925, 90 council houses were constructed in Kingston Road.[102] Private residential developments also occurred around the same time, including the construction of the St Mary's Road estate, on the site of the former Elm Bank mansion, south of the town centre.[103]

The Givons Grove estate, to the south of the town, was developed in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Originally a constituent of Thorncroft Manor, it was an area of arable land, known as "Gibbons Farm", named after a prominent local family.[104][n 7] In 1919, the estate was bought by the aircraft manufacturer, Humphrey Verdon Roe, whose wife, Marie Stopes, would live at Norbury Park for 20 years from 1938.[104] It was sold to a consortium of developers in 1927, who divided the land into plots for housing.[105] Similarly in 1935, Yarm Court was sold and the estate developed for housing.[106]

Following the end of the Second World War, new housing was constructed to the north of the town centre, along Cleeve, Kingston and Copthorne Roads, to replace properties damaged by bombing.[107]

Leatherhead in the world wars

At the start of the First World War, members of the 20th Battalion of the University and Public Schools Brigade of the Royal Fusiliers were billeted with local residents. The recruits were primarily drawn from the Manchester area and underwent training at Randalls Farm.[108][109] The Kensington Rifles of the London Regiment were also garrisoned in the town in the month before their deployment to the Western Front in April 1915.[110] Later that year, the first of 63 Belgian refugees arrived in Leatherhead, remaining in the town until the end of the war.[111][112]

Concerns that the town's water supply might be poisoned by enemy spies, prompted the authorities to arrange a guard on the waterworks on Guildford Road. Many of the duties were undertaken by the local Scout troop and members of the Boys' Brigade, which was affiliated with St Mary's Church.[111] Many local men joined the Dorking and Leatherhead Battalion of the Volunteer Training Corps, which was formed with the intention to defend the local area in the event of invasion.[113] In October 1914, a Red Cross Hospital opened on Bull Hill. By March 1915 it had 33 beds and was fully occupied. It closed in February 1919.[112] Elsewhere in the town, the Forty Foot recreation ground was used to grow wheat[114] and Venthams, a local firm of coachbuilders, began to manufacture munitions.[115][n 8]

Leatherhead was again a garrison town in the Second World War. Troops from the Royal Corps of Signals were billeted in late 1939[116] and a year later, the first Canadian soldiers began to arrive in the local area.[117] From September 1939, children from Streatham and Dulwich were evacuated to Leatherhead and the Royal School for the Blind was taken over by King's College Hospital. The cottage hospital on Poplar Road opened in May 1940 and by June of that year was treating 78 members of the British Expeditionary Force, who had been evacuated from Dunkirk.[116] The Goblin factory in Ermyn Way was used to make munitions, including mine sinkers, shell fuses and camouflage netting.[118]

From the outbreak of war, the defence of Leatherhead was coordinated by the XII Corps of Eastern Command, reinforced from July 1940 by VII Corps GHQ Mobile Reserve. The 3rd Infantry Brigade of the 1st Canadian Division was posted to Dorking and Leatherhead, and was responsible for completing the construction of Young Street between Givons Grove and Fetcham. The local unit of the Home Guard, Company F of the 6th Battalion of South Eastern Command, was formed with 200 recruits in May 1940. The training centres for the company included the Drill Hall on Kingston Road and an anti-tank obstacle was installed at the east end of the High Street, close to the Leatherhead Institute. The Home Guard company was disbanded four years later, once the threat of invasion had passed.[119]

Leatherhead experienced two main periods of bombing during the war. The first wave of attacks took place from late 1940 until early 1941. During the first raid, early in the morning on 27 August 1940, 20 high-explosive bombs were dropped along the border with Ashtead. The clubhouse of the golf club suffered a direct hit, but the civilians taking cover in the shelter beneath it were fully protected and survived without injury. In October of the same year, the oil storage tanks next to the waterworks were set alight by an incendiary bomb. The resulting fires could not be extinguished until more than 24 hours later.[120] In March 1941, St Andrew's Catholic School was almost completely destroyed by a bomb.[121] During the second period of bombing, in the summer of 1944, 16 V-1 flying bombs landed in the Leatherhead area, including one at Thorncroft Manor.[122]

National and local government

UK Parliament

Leatherhead is in the Epsom and Ewell parliamentary constituency.

County council

Councillors are elected to Surrey County Council every four years. The town is part of the 'Leatherhead and Fetcham East' ward.

| First Elected | Member | Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Tim Hall[123] | Leatherhead and Fetcham East | |

District council

Five councillors represent the town on Mole Valley District Council (the headquarters of which are in Dorking):

| Election | Member | Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Bridget Kendrick | Leatherhead North[124][125] | |

| 2019 | Keira Vyvyan-Robinson | Leatherhead North[126] | |

| 2022 | Josie Brinkier | Leatherhead North[127] | |

| 2021 | Simon Moss | Leatherhead South[128] | |

| 2022 | Joanna Slater | Leatherhead South[127] | |

Leatherhead is represented by a swan on the crest of the Mole Valley District Council coat of arms.[129]

Twin town

Since 2004, Leatherhead has been twinned with Triel-sur-Seine (Île-de-France, France).[130]

Demography and housing

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leatherhead North | 307 | 906 | 575 | 1,381 | 6 | 2 |

| Leatherhead South | 737 | 331 | 171 | 670 | 4 | 4 |

Region-wide, 28% of dwellings were detached houses and 22.6% were apartments.

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leatherhead North | 7,035 | 3,177 | 19 | 31 | 617 |

| Leatherhead South | 4,281 | 1,913 | 44 | 30 | 637 |

The proportion of households who owned their home outright compares to the regional average of 35.1%. The proportion who owned their home with a loan compares to the regional average of 32.5%. The remaining % is made up of rented dwellings (plus a negligible % of households living rent-free).

Public services

Utilities

The town gasworks, close to the junction of Kingston Road and Barnett Wood Lane, were built in 1850 by the Leatherhead Gas Company. The first gas was produced in February 1851 and was primarily used for street lighting, but was also supplied to some private houses.[131] Until the railway was opened in 1859, coal was delivered by road from Epsom.[132] In 1911, the Leatherhead company acquired that of Cobham and, from 1929, also supplied gas to Woking via a connection at Effingham Junction. In 1936, the company was acquired by the Wandsworth Gas Company and the Leatherhead gasworks closed two years later.[131]

The first public water supply in Leatherhead was created in 1884, when a stream-driven pumping station was constructed in Waterways Road.[133] The works, designed by John William Grover, were capable of lifting 90,000 litres (20,000 imp gal) per hour to a reservoir on Reigate Road.[133][134] A second diesel-powered station was constructed alongside the first in 1935 and was later converted to electric power. The steam-powered works were demolished in 1992.[133]

An electricity generating station was opened in Bridge Street in 1902. Initially it was capable of generating 75 kW of power, but by the time of its closure in 1941, its installed capacity was 2.2 MW.[132] Under the Electricity (Supply) Act 1926, Leatherhead was connected to the National Grid, initially to a 33 kV supply ring, which linked the town to Croydon, Epsom, Dorking and Reigate. In 1939, the ring was connected to the Wimbledon-Woking main via a 132 kV substation at Leatherhead.[132][135]

Emergency services

Leatherhead Police Station was on Kingston Road, to the north of the town centre. It closed in 2011. The building was demolished and retirement apartments were built on the site.[136] In 2021, the local police force is Surrey Police and the nearest police station to the town is at Reigate.[137][138] The headquarters of the Police Federation of England and Wales is in Leatherhead.[139]

The Vestry was responsible for organising the local fire service in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The west door of the parish church was enlarged in 1759, in order to accommodate the town fire engine, which was housed in the tower.[46] In 1821, the engine was moved to an existing building on North Street and a new fire station was built on the same road in 1859. The first motor fire engine was delivered to the town in 1926 and was housed in a new building close to the river.[46] In 2021, the local fire authority is Surrey County Council and the statutory fire service is Surrey Fire and Rescue Service.[140] Leatherhead Ambulance Station, in Kingston Road, is run by the South East Coast Ambulance Service.[141]

Healthcare

The first hospital in Leatherhead was opened in Clinton Road in 1893. As a small cottage hospital, it only had seven or eight beds and was supervised by a matron.[142] It closed in 1902, having accrued a debt of £130. A replacement facility, the Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital (QVMH), on Epsom Road, was opened in 1905. It was built on land donated by Walter Cunliffe, who lived at Tyrells Wood.[143] Initially it had 6 beds for adults and one cot for infants, but by 1928, it had expanded to 17 beds.[144] The QVMH closed at the end of the Second World War.[143]

Leatherhead Community Hospital, on Poplar Road, was opened in 1940 and was built on land donated by Charles Leach. Initially it had 40 beds and came under the management of Epsom Hospital, although it had its own medical committee. By 1960, the hospital had expanded to 52 beds,[144] but in 2014, the in-patient wards were closed to allow the improvement of outpatient services.[145] The NHS has retained ownership of the hospital, but many services are now run by CSH, a not-for-profit organisation.[144] The X-ray radiography department is run by the Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust.[146]

The nearest hospital with an A&E is Epsom Hospital, 5.3 km (3.3 mi) away.[147] As of 2021, the town has two GP practices, on Kingston Road and Upper Fairfield Road.[148]

Transport

Rail

Leatherhead railway station is to the west of the town centre and is managed by Southern. It is served by trains to London Victoria via Sutton, to London Waterloo via Wimbledon, to Horsham via Dorking and to Guildford via Bookham.[149]

Buses

Route 21 (Epsom – Leatherhead – Crawley) is run by Metrobus and route 408 (Epsom – Cobham) is run by Falcon Buses.[150] Route 465 from Kingston upon Thames to Dorking via Leatherhead is run by London United.[151] Route 478 to Guildford is run by Reptons Coaches and Route 479 from Epsom to Guildford via Leatherhead is run by Arriva Kent & Sussex and Stagecoach.[150]

Long-distance footpaths

Leatherhead station is the northern terminus of the Mole Gap Trail, which rus south through Norbury Park to Dorking station.[152]

Education

Early schools

The earliest record of a school in Leatherhead is from 1596, when reference is made to a charity school for ten boys, which was probably held in the tower of the parish church.[46] By 1712, the school had expanded to included eleven girls[153] and, later that century, two bequests to fund the[salary of a schoolmaster are recorded.[46]

In 1838 a boys' school was established in Highlands Road by the then Vicar, Benjamin Chapman, and a girls' school followed a year later.[46] The two institutions were National schools and were funded by a combination of local subscriptions and grants from the National Society for Promoting Religious Education.[154]

Maintained schools

Leatherhead Trinity School opened in 2010, having been created by a merger of three existing schools. It traces its origins to the All Saints School, which opened in 1877 in Kingston Road. Trinity School is a primary school and educates children up to the age of eleven.[155]

St Peter's Roman Catholic Primary School was founded in September 1947 and was initially located next to St Peter's Church in Garlands Road. The school's present site in Grange Road was opened in 1958.[156]

Therfield School was founded in Kingston Road in 1913 as the County Upper Mixed Senior School. It moved to Dilston Road in 1953[157] and was renamed in 1964 after John de Therfield, a former lord of the manor of Pachesham, who was awarded the land in 1205 by King John.[158][159]

St Andrew's Catholic School was founded in Grange Road in 1935 by five nuns from the Order of St Andrew. The main building was constructed in 1952 and, in 1971, the school became a co-educational comprehensive.[158]

West Hill School is a special school for children with learning needs.[160] It was founded at West Hill, Epsom in 1960[161] and moved to Leatherhead three years later.[158] Fox Grove School, a second school for pupils with special Education Needs, opened in September 2021 in Molesey. It is due to move to Leatherhead, to a site adjacent to West Hill School, in Spring 2022.[162]

Independent schools

Downsend School was founded in Hampstead in 1898[163] and moved to its current site in stages between 1918 and 1940.[164] The school underwent a period of expansion in the late 1970s and 1980s, which included the purchase of pre-preparatory departments in Leatherhead, Ashtead and Epsom.[163] In 2002, the school was sold by the Linford family (who had owned it since its opening) to Asquith Court Schools Ltd and it was bought by Cognita in 2006.[163] In 2017, the school announced that it would build a new study centre to accommodate students studying for GCSEs.[165]

St John's School was founded in St John's Wood in 1851 by Ashby Haslewood and moved to Leatherhead in 1872.[166][167] Initially intended for the sons of poor clergymen, the school began to accept fee-paying pupils at the start of the 20th century. In 1989, girls were accepted into the sixth form and the school became fully coeducational from 2012.[166] Several parts of the school are Grade II listed, including the library, formerly the chapel, which was built in 1876.[168]

Royal School for the Blind

The School for the Indigent Blind was founded at St George's Fields, Southwark in 1799 and, for the first 102 years of its existence, was based in London.[169] In 1900, it purchased 15 acres of land in Leatherhead and construction of a new building, in Highlands Road, began the following year. The new school, capable of accommodating up to 250 students, opened in 1904.[143] The school was granted royal patronage by George V in 1911, at which point it became known as the Royal School for the Blind.[169]

By the mid-1930s, the focus of the school had changed from classroom-based learning to the teaching of practical skills in a workshop setting. During the Second World War, the building was requisitioned by King's College Hospital and, although part of the premises were returned to the school in 1946, a group of Chelsea Pensioners continued to live on the site until the 1950s.[143] A redevelopment took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which included converting the dormitories into apartments. Students were increasingly encouraged to take responsibility for their everyday living, with the aim of facilitating their integration into wider society.[169]

The charity adopted the name "SeeAbility" as its operating identity in 1994 and, later in the same decade, began to transition away from offering residential education and towards providing community-based support. In the early 2000s, the main school building was sold and converted to apartments. It is now known as Lavender Court.[170] The headquarters of the charity has since moved to Epsom.[171]

Places of worship

Anglo-Saxon minster

The church mentioned in Domesday Book is thought to have been an Anglo-Saxon minster, a large church with a small team of priests who ministered to the royal vill and its dependent parishes. It is described as a belonging to Ewell and being held by Osbern of Eu, a prebend at St Paul's Cathedral.[172][173] Its location in the town is unknown, but an enclave of land in the north west of the parish is recorded as belonging to Ewell in the 13th century and this may be the remnant of the glebe lands of the former minster.[173] The church was probably a constructed from wood[174] and, like other similar minsters, likely lost influence as Norman manors superseded the Anglo-Saxon hundreds as the principal division of local administration.[173]

St Mary and St Nicholas Church

The Church of St Mary and St Nicholas is thought to have originally been built as the estate chapel for the manor of Thorncroft. Although it is not mentioned in Domesday book, the oldest parts date from around 1080 and it may have superseded the Anglo-Saxon minster as the parish church at the start of the 12th century. Shortly after 1100, it was granted to Colchester Abbey, which held it until 1279.[172][175] The earliest parts of the building that survive are from the 1240s, when the church is thought to have undergone a major expansion that included the addition of side aisles. Much of the chancel dates from the first half of the 14th century and this work may have been commissioned by Leeds Priory in Kent, which was given the church by Edward III in 1341. The dedication to Mary and Nicholas, who were the joint patrons of the Priory, probably occurred at this time.[175][176]

The tower was built in around 1500 and is set at an angle to the rest of the building, so that its east wall protrudes into the nave. It originally had a tall spire, which was blown down in the Great storm of 1703. A major rebuilding of the church took place in the second half of the 19th century, during which much of the roof was replaced.[175][176] Renovation works between 2018 and 2020, uncovered several vaults beneath the floor including one belonging to the Boulton Family who had lived at Thorncroft Manor in the 18th century.[177]

The churchyard contains the Commonwealth war graves of 12 British service personnel of the First and Second World Wars.[178]

Catholic Church of Our Lady and St Peter

The Catholic Church of Our Lady and St Peter was constructed in 1923 and was partly financed by the newspaper proprietor, Sir Edward Hulton.[179] The Gothic Revival building was designed by Joseph Goldie and the stained glass windows were installed in the 1930s. The Stations of the Cross were designed in Caen stone by the sculptor Eric Gill.[180]

Methodist Church

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, visited Leatherhead only once in his lifetime. On 23 February 1791, he preached his final sermon in a house on Bull Hill, one week before his death.[181][182] Despite his visit, there appears to have been no significant Methodist community in the town until the mid-19th century, when a small group of worshipers began meeting in Bridge Street.[183][184] The first purpose-built place of worship, the "Iron Chapel", so-named because it was primarily constructed of metal, was erected in 1887 on Church Road. The following year, the congregation numbered around 50, but grew rapidly to over 400 by 1891. Two years later, a new brick building, the present church, was constructed. The Iron Chapel, behind the new church, remained standing and was used for the Sunday school, but was replaced in 1903 by a new hall.[183]

Disciples Church

The Disciples Church is part of the Calvary Chapel Association of evangelical churches. It was formed in 2007 and adopted its present name in 2012. It meets at the Woodlands School on Forty Foot Road.[185]

Culture

Art

J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) is among the artists who have been inspired to paint scenes of the town and local area. His pencil and watercolour composition Leatherhead, Surrey, from across the River Mole, with cattle watering in the foreground was probably created in the summer of 1797, when he staying at Norbury Park. The painting was sold at Christie's in 2014 for £35,000.[186] Other artists who have worked in the town include John Hassell (c. 1767–1825) and John Varley (1778–1842).[187][188][189]

The works of public art in the town include ornamental ironwork at the King George V Memorial Park[190] and at the junction between the High Street, North Street and Bridge Street.[191][192]

Theatres and cinemas

The first presentation of a cinematograph film in the town took place at the Leatherhead Institute in October 1898. The following year, a second screening took place at the Victoria Hall in the High Street, which had been built in 1890.[193][194] By 1914, the Victoria Hall was renamed to become the Grand Theatre and was operating as a cinema with a capacity of 550. Further name changes took place before 1946, around which time the venue became known as the Ace Cinema.[195]

In 1949, the Ace Cinema was converted to a 300-seat theatre and a year later, the Leatherhead Theatre was established at the venue.[196][n 9] The theatre operated until 1969, but as its popularity increased, its size became restrictive and there was a need for a new and better-equipped performing arts venue in the town.[196]

The Thorndike Theatre, in Church Street, was designed by Roderick Ham in the modernist style[199][n 10] and was opened in 1969 by Princess Margaret.[200] Named for the actor Sybil Thorndike, its construction was primarily paid for by private donations, with some additional funding from the Leatherhead UDC and the Arts Council.[196] Although it was initially popular, the theatre regularly ran operating deficits and, following several years of cuts in public subsidy, it closed in 1997 with a total debt of almost £1.2 million.[196][202] It reopened in 2001 as a part-time theatre,[202] cinema, community space and meeting place for the evangelical group, Pioneer People.[200][199] The annual Leatherhead Drama Festival, for amateur theatre groups, was launched at the theatre in 2004 and ran for 16 years.[203]

Literature

Leatherhead features in the novel The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, first published in 1897. On about the tenth day following the Martian invasion of Earth, the entire town (where the narrator has sent his wife for safety) is obliterated: "it had been destroyed, with every soul in it, by a Martian. He had swept it out of existence, as it seemed, without any provocation, as a boy might crush an ant-hill, in the mere wantonness of power."[204]

The Sherlock Holmes short story "The Adventure of the Speckled Band" is partly set near the town. During the story, Holmes and Watson travel to Leatherhead from Waterloo station by train. It was first published in 1892 and is one of 12 featured in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle.[205][206] The 1984 interactive fiction video game Sherlock, developed by Beam Software, is partly set in Leatherhead.[207][208]

Music

The Leatherhead Operatic Society was founded as the Leatherhead Pierrots in 1904. Two years later, the group was reformed as the Leatherhead & District Amateur Dramatics & Operatic Society and gave its first performance, H.M.S. Pinafore by Gilbert and Sullivan. The group performed at the Victoria Hall until 1922, when the venue was turned into a cinema. For the next seventeen years, the society used a number of venues in the local area, until the Crescent Cinema opened in 1939. Since 1970, the group has staged its summer performances at the Thorndike Theatre and the Leatherhead Theatre, with a brief hiatus between 1996 and 2002.[209][210]

The Leatherhead Choral Society (LCS) was formed in 1907, but its early history is unclear. It was refounded in 1928 to take part in the Leith Hill Musical Festival. Kathleen Riddick conducted the group in 1939 and LCS continued to perform during the Second World War. A musical work was composed by William Blezard to celebrate the society's 50th anniversary in 1978.[211] In recent years, the LCS has typically given concerts in the summer and in early December, as well as participating in the Leith Hill Musical Festival around Easter.[212]

The Leatherhead Orchestra traces its origins to an adult education class established c. 1954, but was formally founded in around 1958 by Kathleen Riddick.[213] Since 2015, the group has given three concerts each year.[214]

The Leatherhead Town Band was founded in 1887. Its activities ceased during the First and Second World Wars and, on its reformation in 1947, it was known as the Bookham and District Silver Band. In 1974, it changed its name again to the Mole Valley Silver Band, to reflect the formation of the new local authority area.[215][216] The band performs regularly in and around the towns of Leatherhead and Dorking.[217]

The band John's Children, which included sometime frontman Marc Bolan, was formed in the town in 1963 by Andy Ellison and Chris Townson, former pupils of nearby Box Hill School. They occasionally appeared at the Chuck Wagon Club on Bridge Street.[218][219]

Surrey Sound recording studio was established in 1974 by producer Nigel Gray in a former village hall in the north of the town. Early demo pieces for, among others, the Wombles and Joan Armatrading were followed, by the recording of much of the early repertoire of the Police.[220][n 11] Other groups recording there included Godley & Creme, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Rick Astley, the Lotus Eaters, Alternative TV and Bros. The studio was sold by Gray in 1987.[220]

Robyn Hitchcock refers to Leatherhead in the song "Clean Steve".[221]

Television and film

Leatherhead has been mentioned in a number of films and television programmes. The film I Want Candy, released in March 2007, is partly set in the town. Brooklands College, Weybridge was used as the filming location for the fictional "Leatherhead University".[222]

Monty Python's Flying Circus refers to Leatherhead in the "Red Indian in Theatre" sketch. Eric Idle, in Native American costume says, "When moon high over prairie, when wolf howl over mountain, when mighty wind roar through Yellow Valley, we go Leatherhead Rep - block booking, upper circle - whole tribe get it on three and six each."[223] The television sketch show That Mitchell and Webb Look took a jab at Leatherhead in series two, episode four. In one sketch, a librarian comments to a customer that she is "possibly one of the stupidest people I've ever met. And I lived in Leatherhead for six miserable years."[224] The house that was used as the filming location for Arthur Dent's residence for the TV series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, is in Leatherhead.[225]

Sport

Leisure Centre

The Leisure Centre was opened in 1975 by the Leatherhead Urban District Council[226] and was extended in the 1980s with the addition of the Mole Barn. Plans to build a new centre on the site were drawn up by Mole Valley District Council prior to 2006, but instead the facility was given a 20-month, £12.6m refit and a further extension, which was opened by the Duke of Kent in March 2011.[227] The upgraded centre includes a redesigned reception and entrance area, a new gym, aerobics studio, sauna and play areas.[228][229] In July 2023, a report to the cabinet committee of Mole Valley District Council stated that 750,000 visits were made each year to Leatherhead Leisure Centre.[230]

Cricket

Cricket has been played at Leatherhead since at least 1840, when a match is recorded against a team from Dorking. The Leatherhead Cricket Club was founded in 1850[231] and initially played its home games at the Kingston Road recreation ground. It moved to Fetcham Grove in the 1930s.[226]

Football

Leatherhead F.C., commonly known as "The Tanners",[226] was formed in 1946 as a result of the merger of two existing clubs, Leatherhead Rose and Leatherhead United. Leatherhead Rose, founded c. 1907, drew the majority of its players from the Leatherhead Common area and was named after the Rose Coffee Rooms on Kingston Road; Leatherhead United was formed in 1924 and the following season were Division One Champions of the Sutton and District League.[233][234][235]

Following the merger, the new club adopted Fetcham Grove as its home ground and, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, were champions of the Surrey County Senior League for four consecutive years.[233] In 1969, the team won the Surrey County FA Senior Challenge Cup, the Senior Shield and the Intermediate Cup. They were semi-finalists in the 1971 and 1974 FA Amateur Cup competitions.[226] The Tanners achieved national press coverage in the 1974–75 season, when they were drawn against First Division Leicester City at home in the FA Cup Fourth Round Proper.[226][233] In the 2017–18 FA Cup they reached the second round proper, in which they played against Wycombe Wanderers.[236]

Golf

The Leatherhead Club was founded as the Surrey Golf Club, but adopted its present name in 1908. The 18-hole course was designed by the Scottish golfer, Peter Paxton, and the first nine holes opened in October 1903. The Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, was one of those who played at the course in 1907. In 1928, Alf Perry joined as Club Professional and, seven years later, he won the 1935 Open Championship at Muirfield. The clubhouse suffered bomb damage during the Second World War. The construction of the M25 motorway in the late 1970s, necessitated changes to the layout of the southern part of the course.[237][238]

The 18-hole Tyrells Wood Golf Course was designed by James Braid in the grounds of Tyrells Wood House in 1922.[239][n 12] The Club opened two years later.[239]

Pachesham Golf Centre opened in 1989 as a nine-hole course, but was remodelled in 2014 to a six-hole course. The centre has a 28-bay, floodlit driving range, which is the longest in Surrey.[242][243]

Beaverbrook golf course, to the south of Leatherhead, was designed by David McLay-Kidd and Tom Watson. The 7,100 yard, 72-par course opened in the grounds of Cherkley Court in 2016.[244][245] The construction of the course was opposed by local residents and environmental campaigners, who mounted a series of legal challenges to the development.[246][247] Construction of the clubhouse was completed in 2018.[244]

Tourist attractions

Bocketts Farm

Bocketts Farm covers an area of 52 ha (128 acres) to the southwest of the town.[44] Formerly part of the manor of Thorncroft, it was subinfeudated around 1170.[248] Both the farmhouse and the timber-framed granary date from around 1800 and are Grade II listed.[249][250] The farm was purchased by the Gowing family in 1990 and was opened to the public two years later.[251]

Leatherhead Museum

Leatherhead Museum was opened in 1980 by the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. It houses a wide range of historical artefacts and permanent displays explain the history of the town from its origins to the present day. Hampton Cottage, the building in Church Street in which the museum is based, dates from before 1682.[252]

River Mole local nature reserve

The River Mole local nature reserve is a 23.3-hectare (58-acre) protected corridor that stretches along the banks for the river from Young Street (in the south) to Waterway Road (in the north).[253][254] It was designated in 2005 for its diversity of plant and animal species.[253]

Notable buildings and landmarks

All Saints' community café and hub

All Saints' Church on Kingston Road was consecrated in February 1889 as a daughter church to St Mary's. It was designed by the architect, Arthur Blomfield, and was built to serve a new area of housing under construction to the north of the town centre.[255] On opening, the church could accommodate 300 people, but was later extended with the addition of a lady chapel.[256] By 1980, the congregation had dwindled and the building was in need of repair. A decision was taken to convert the nave of the church to a community space, while retaining the chancel as a place of worship.[255] The dual-purpose facility was rededicated by the Bishop of Dorking in March 1982.[256] In 2005, the nave of the church was converted to a Youth Project Café, known as "B Free", to be a space for young people to meet and socialise.[255] In 2014, the Leatherhead Youth Project, launched a new social enterprise at the church called "AllSaints". The project supports disadvantaged young people, especially those not in education, employment or training, and provides opportunities for participants to gain employment and life skills.[257]

Cherkley Court

Cherkley Court was constructed in around 1870 for Abraham Dixon, a wealthy industrialist from the Midlands.[258][259] It was substantially rebuilt after a fire in 1893[258][260] and was sold in 1910 to Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, the Canadian-born owner of the Daily Express.[261] Following the death of Beaverbrook's son in 1985,[262] the estate was owned by the Beaverbrook Foundation until 2011, when it was bought by a consortium of private investors.[263] Despite considerable local opposition,[264] the house was converted to a luxury hotel, spa and golf course, which opened in 2017.[265][266]

Cradlers

The building at 33 and 35 High Street, commonly known as "Cradlers", is a late-medieval open hall house, formerly owned by the Manor of Thorncroft. It most likely originated as a farmhouse and was built on the edge of one of the common fields. Although the earliest surviving records of the building date from 1527,[267] the construction methods used suggest that it was built in the 13th or 14th century (most likely between 1320 and 1360).[268] The western part of the building (now number 33) was constructed as a single-storey hall, but the height of the walls was later raised and an upper floor inserted. The larger eastern part (number 35) was built as two storeys from the outset. In the late medieval period, the rooms closest to the street were probably used as living quarters, but the northernmost third of the wing may have contained a workshop and hayloft.[267]

Although much of its original timber frame survives, Cradlers has been altered at several points in its history.[268] In the 17th century, a chimney stack and internal staircase were added[269] and the roof was rebuilt around the same time, probably reusing used timbers from other buildings. In the early modern period, Cradlers may have served as a tavern or hostelry[268] and at different times in the 19th and 20th centuries, it housed a butchers, a fruiterers and a ladies' outfitters.[270] As part of a renovation project carried out in the mid-1980s, the modern shopfronts were removed and the street-facing frontage was restored to its original position.[268][269]

Leatherhead Institute

The Leatherhead Institute was built in 1892. It was given to the town by Abraham Dixon,[271] who wanted the building to be used to provide educational, social and recreational opportunities to local residents.[259] During the Second World War, it housed the local Food and Fuel Offices.[272] A major restoration project was completed in 1987.[273]

Running Horse pub

The Running Horse pub, at the east end of Leatherhead Bridge, is one of the oldest buildings in the town. It is a late-medieval open hall house and was part of the Manor of Thorncroft. Much of the timber frame is original and probably dates from the late 15th century, although the roof was later rebuilt. Later alterations include the insertion of the first floor in the 17th century and installation of interior panelling in the 18th century.[274][275]

Sweech House

The timber-framed Sweech House, on Gravel Hill, is one of the oldest buildings in Leatherhead. Its name is thought to derive from "switch", indicating that it stood close to a road junction.[276] The land on which it stands may have belonged to the manor of Minchin during the late-medieval period. The southernmost part of the building is the oldest and dates from the 15th century. It was probably constructed as a farmhouse and originally it had an open hall structure.[277][278] In the late 16th century, it was extended to the north in two separate phases.[277] At different points in its history, the building has been divided into up to four cottages, most likely to provide accommodation for farm labourers. Sweech House was donated to the Leatherhead Countryside Protection Society in the 1940s.[278]

The Mansion

The Mansion, in Church Street, houses the public library, register office and council offices.[279][280] A map of the town from 1600 shows a house on the site, which may formerly have been the manor house for the manor of Minchin.[33][n 13] During the late Elizabethan period, it was the home of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels, in effect the official censor of the time.[279][281] and Elizabeth I is thought to have dined with him in Leatherhead in August 1591.[279][n 14]

The external appearance of The Mansion largely dates from 1739, when the house was rebuilt in red brick, although a partial remodelling took place c. 1810.[280] From 1846 until some point in the 1870s, the building was used as a boarding and day school for around 50 boys, who were taught using the Jacotot education system. In 1949, The Mansion was subject to a compulsory purchase order and was acquired by Surrey County Council and Leatherhead UDC for use as a health clinic and the public library.[279] During a refurbishment in 2000, the library was moved from the ground floor to the south range and the space released was repurposed for the Registry Office.[279][280]

Thorncroft Manor house

The current Thorncroft Manor house was designed c. 1763 by the architect, Robert Taylor, for the politician and businessman, Henry Crabb-Boulton. It is built in a Neo-Palladian style, influenced by the early Rennaissence, with light Rococo ornamentation. The building was enlarged with the addition of a rear wing in 1789, possibly designed by George Gwilt. The engineering firm, Howard Humphreys & Sons, purchased the house in 1971 and subsequently constructed additional office space, glazed with reflective glass.[38][283]

War memorial

The war memorial in North Street was designed by Stock, Page and Stock, a London firm of architects and was dedicated in April 1921.[284] It consists of a long, single-storey building with 11 open arches, constructed of brick and flint. The arches face a terraced garden, in which there is a free-standing cross made of Portland stone.[285] The land on which the memorial stands was given to the town by Charles Leach, who funded much of the building work and whose son had been a second lieutenant in the Scots Guards. In total, 186 names are inscribed on stone tablets inside the cloister-like structure, of whom 117 died in the First World War.[284] The memorial is protected by a Grade II listing.[285]

Wesley House

The Art Deco Wesley House, on Bull Hill, was built in 1935 as the offices of the Leatherhead Urban District Council (UDC).[286][n 15] It was designed by the architects C. H. Rose and H. R. Gardner and was constructed of red brick. The original council chamber is preserved at the rear of the property.[286] Wesley House was vacated by the UDC in 1983, when it became part of Mole Valley District Council.[288][289]

Parks and open spaces

King George V memorial gardens

The memorial gardens on Bull Hill, to the north of the town centre, were opened in 1936, following the death of George V.[290] The 0.39 ha (0.96-acre) site is managed by Mole Valley District Council and has been protected by the Fields in Trust charity since 1938.[291]

Leach Grove Wood

Leach Grove Wood is a 2.9 ha (7.2-acre) area of woodland, adjacent to Leatherhead Hospital, owned by the NHS.[292][293] It is named after Charles Leach, who donated the land on which the hospital is built, to the town.[294] In 2013, a group of local residents applied to register the wood as a village green, to guarantee public access to the site in perpetuity.[295] The registration was upheld by the High Court in 2018.[296] The NHS subsequently successfully appealed against the registration at the Supreme Court and the village green status was removed.[293][297]

Mansion Gardens

The Mansion Gardens is a small formal garden between The Mansion and the River Mole.[298]

Park Gardens

The Park Gardens form the frontage to St Mary's Parish Church at the north end of Gimcrack Hill.[298] The 0.52 ha (1.3-acre) site has been protected by the Fields in Trust charity since 2018. In the gardens, there is a memorial stone to Harold Auten, who was awarded the Victoria Cross in September 1918.[299]

Recreation grounds

There are two recreation grounds in Leatherhead. The Fortyfoot ground contains a children's playground and a football pitch, as well as the bowling green for Leatherhead Bowling Club.[300] The playground was upgraded in 2017 and includes a sensory garden, a trampoline and a zip line.[301][302] The Kingston Road ground has a children's playground, football pitch, pavilion and a sensory garden.[300] A new skatepark was installed at the ground in 2017–18, part-funded by a £20,000 donation by the London Marathon Charitable Trust.[303][304] The skatepark adjacent to Leatherhead Leisure Centre was refurbished in 2020.[305]

Notable people

- Harold Auten (1891–1964), recipient of the Victoria Cross during the First World War, was born in Leatherhead.[306][307]

- John Drinkwater Bethune (1762–1844), army officer, lived at Thorncroft Manor just outside the town from about 1838 until his death and is buried in the churchyard of the parish church.[308]

- Sir Thomas Bloodworth (1620–1682), Lord Mayor of London during the Great Fire of 1666, lived at Thorncroft Manor.[33][309]

- Ted Bowley (1890–1974), English Test cricketer.[310]

- Michael Caine (born 1933), lives in Leatherhead and is patron to the Leatherhead Drama Festival.[311]

- Donald Campbell (1921–1967), Bluebird pilot and fastest man on land and water, lived in Leatherhead.[312]

- John Campbell-Jones (1930–2020), former Formula One racing driver.[313]

- Leonard Dawe (1889–1963), footballer, teacher and crossword compiler for The Daily Telegraph; while living in Leatherhead in 1944 he was wrongly suspected of espionage by inserting codewords for Operation Overlord into his puzzles.[314]

- Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth (1747–1817), accomplished Royal Naval officer who served under Nelson.[315]

- Andy Ellison (b. 1946) and Chris Townson (1947–2008), founding members of the band John's Children, and former pupils at Box Hill School.[316]

- Badri Patarkatsishvili (1955–2008), businessman, collapsed and died in his mansion in Leatherhead.[317]

- Richard Patterson (b. 1963) and his brother Simon Patterson (b. 1967), both artists, were born in the town.[318][319]

- Jean Ross (1911–1973), an English writer was educated in Leatherhead and briefly confined in a nearby sanatorium as a young woman.[320]

- Madron Seligman (1918–2002), Member of the European Parliament and friend of Edward Heath.[321]

- Marie Stopes (1880–1958), family planning pioneer, lived in the town.[322]

- Richard Wakeford (1921–1972), recipient of the Victoria Cross in the Second World War, died at Leatherhead.[323]

- Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1890–1976), archaeologist and broadcaster, lived at "The Bothy", Downs Lane from September 1973 until his death.[324][325]

- Edward Wilkins Waite (1854–1924), local landscape painter, was born in the town, was educated at the school at The Mansion and later lived at Long Cottage, Church Street[326][327]

Notes

- ^ The Town Bridge was rebuilt by George Gwilt in 1782-3 and may originally date from the late medieval period.[3]

- ^ Much of the catchment area of the River Mole above Leatherhead is on impermeable Weald Clay and the water level therefore rises rapidly after heavy rainfall.[13] Serious flooding events have taken place in Leatherhead in October 1891,[14] September 1968[15] and December 2013.[16][17]

- ^ The route of Stane Street, the Roman road from London to Chichester, passes about 2.5 km (1.6 mi) southeast of the town.[20]

- ^ The Swan Hotel, first recorded in 1637, stood at the junction of the High Street and Church Street.[63] Most stagecoaches stopped at the inn, which was described in a Directory in 1791 as "a very genteel house, with good accommodation, most excellent stabling and good post chaises with able horses for hire."[61] The Swan closed in 1936, was sold for development and was subsequently demolished.[64][65]

- ^ Dorincourt was acquired by the Queen Elizabeth's Foundation for Disabled People in 1953.[82] The charity's Independent Living Service is based at the site and provides residential care for up to 43 people with complex physical disabilities and learning disabilities.[83]

- ^ The Swan shopping centre is named after the former Swan Hotel.[64]

- ^ Givons Grove House was built in the late 1780s for Henry Boulton, the then leaseholder of Thorncroft Manor and the owner of the Pachesham estate. The house was later occupied for a short time by Sir William Altum, but remained in the ownership of the Boulton family until 1859. In 1865, it was sold to Thomas Grissell, the owner of Norbury Park.[104]

- ^ The precise nature of the contribution of the Venthams factory to the war effort is unclear and, owing to secrecy rules, there are only sporadic mentions of munitions manufacture in the local press.[115]

- ^ The Leatherhead Theatre was founded by Hazel Vincent Wallace and Michael Marriott as a permanent home for the Under Thirty Theatre Club, which had been established in London in 1948 by the actor, Oscar Quitak.[196][197][198]

- ^ The Thorndike Theatre was rebuilt from the former Crescent Cinema, which was originally constructed in 1939 and which was run by a local family until the 1960s.[200][201] Although the exterior walls of the Crescent were retained, the interior, including the 526-seat auditorium and lobby, was built anew for the Thorndike Theatre.[196]

- ^ Police songs recorded at Surrey Sound Studio included "Roxanne" and the band's debut album, Outlandos d'Amour; Reggatta de Blanc and its singles "Message in a Bottle" and "Walking on the Moon"; and the Grammy Award-winning Zenyatta Mondatta and its hit single "Don't Stand So Close to Me".[220]

- ^ Tyrells Wood house was built for the banker, Roger Cunliffe, in around 1880.[240] The house and the surrounding 100 ha (250 acres) were bought by the politician, Henry Keswick in 1913. The estate was sold again in 1922 to the founders of the Golf Club, although not all of the land was required for the course and, in 1925, some land was released for housebuilding.[241]

- ^ It has been suggested that the name "Mansion'" may be a corruption of 'Minchin'.[33]

- ^ The Wetherspoons pub on Leatherhead High Street is named after Edmund Tylney.[282]

- ^ From 1922 until the opening of Wesley House in 1935, the Leatherhead UDC offices were in Surrey House, Church Street.[287]

References

- ^ a b c Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine United Kingdom Census 2011 Office for National Statistics Retrieved 20 December 2013

- ^ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Leatherhead Bridge (Grade II) (1028646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b Coates, Richard (1980). "Methodological Reflexions on Leatherhead". Journal of the English Place-Name Society. 12: 70–74.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connell, M (1977). "Historic Towns in Surrey" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Research Volumes. 5: 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b c "Surrey Domesday Book". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- ^ Ekwall 1940, p. 279

- ^ "Key to English Place-names". University of Nottingham. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Gover, Mawer & Stenton 1934, pp. 78–79

- ^ Coates, Richard (2004). "Invisible Britons: the view from linguistics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 18–20

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, p. 18

- ^ Bull AJ, Gossling F, Green JF, Haywood HA, Turner EA, Wooldridge SW (1934). "The River Mole: its physiography and superficial deposits". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 45: 35–67. Bibcode:1934PrGA...45...35B. doi:10.1016/s0016-7878(34)80032-6.

- ^ "The gale and the floods". Cheshire Observer. Vol. 39, no. 2046. Chester. 24 October 1891. p. 8.

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 261–262

- ^ "Thousands hit by floods and power cuts at Christmas". BBC News. 25 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Murad, Ahmed (26 December 2013). "50,000 homes without power as floods bring blackouts". The Times. No. 71077. London. p. 4.

- ^ a b Lowther, AWG (1956). "A note on the geology of the Leatherhead district of Surrey" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 1 (10): 11–13. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Randall, Nigel; Ayton, Gemma; Jones, Phil; Marples, Nick (2017). "Iron Age and Roman occupation at St John's School, Garlands Road, Leatherhead" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 100: 55–70. doi:10.5284/1069426. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Hall A (2008). "The archaeological evidence for the route of Stane Street from Mickleham Downs to London Road, Ewell" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 94. Surrey Archaeological Society: 225–250. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Hastings (1965). "Excavation of an Iron Age Farmstead at Hawk's Hill, Leatherhead" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 62. Surrey Archaeological Society: 1–43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Salkeld, E (28 February 2020). "Having a field day with Lidar in the Surrey HER". Exploring Surrey's Past. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Hogg, I (2019). "Activity within the prehistoric landscape of the Surrey chalk downland, Cherkley Court, Leatherhead". Surrey Archaeological Collections. 102: 103–129.

- ^ "Norbury Park: Summer all the winter". The Times. London. 13 April 1934. p. 17.

- ^ a b Ruby, A. T. (1968). "The coming of the Saxons" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 3 (2): 45–49.

- ^ Smith, R. A. (1907). "Recent and former discoveries at Hawks Hill". Surrey Archaeological Collections. 20: 119–128.

- ^ Stuttard 1995, pp. 20–22

- ^ Poulton, Rob (1987). "The former Goblin Works Leatherhead: Saxons and Sinners" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 5 (12): 311–317. doi:10.5284/1070745. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Vardey 1988, pp. 28–30

- ^ Powell-Smith A (2011). "Leatherhead". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ Powell-Smith A (2011). "Thorncroft". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Powell-Smith A (2011). "Pachesham". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Benger, FB (1953). "Pen sketches of old houses in this district: The Mansion, Leatherhead" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 1 (7): 7–12. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Harvey, John (1962). "A cartographical survey of the area: VIII Leatherhead in 1782" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 2 (6): 169–170. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Blair, WJ (1977). "A military holding in twelfth-century Leatherhead: Bockett Farm and the origins of Pachensham Parva" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 4 (1): 3–12. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Lowther, Anthony; Ruby, AT; Renn, Renn (1984). "Pachensham, Leatherhead: The excavation of the medieval moated site known as 'The Mounts'" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 74: 1–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Amt, Emilie (2009). "Ela Longespee's roll of benefits: Piety and reciprocity in the thirteenth century". Traditio. 64: 1–56. doi:10.1017/S0362152900002245. JSTOR 27832088.

- ^ a b c Garnier, Richard (2008). "Thorncroft Manor, Leatherhead" (PDF). The Georgian Group Journal. XVI: 59–88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Harvey, John (1962). "The Court Rolls of Leatherhead: The earliest surviving Court Roll of the Manor of Pachenesham" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead and District Local History Society. 2 (6): 170–173. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Ruby, A.T. (1957). "The Manor of Pachenesham, Leatherhead" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 55: 7–17. doi:10.5284/1068894. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Renn, D. F.; Lowther, A.; Ruby, A. T. (1984). "Pachenesham, Leatherhead: The excavation of the medieval moated site known as 'The Mounts'" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 74: 1–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 52–55

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 46

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, p. 128

- ^ Kümin 1996, pp. 250–255

- ^ a b c d e f g Heath, Linda (2000). "Leatherhead: Church and Parish, from the 17th to the 19th century" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 6 (4): 81–87. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 113–116

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 178–179

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 148

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 182

- ^ Ettinger, Jackson & Overell 1991, p. 103

- ^ Ruby, A.T. (1964). "The Leatherhead River" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 2 (8): 228–247. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Renn, D.F. (1971). "The date of the first Leatherhead Bridge" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 3 (5): 153–154. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 59

- ^ Vine 1986, pp. 6–7

- ^ Bogart D (August 2007). "Political Institutions and the Emergence of Regulatory Commitment in England: Evidence from Road and River Improvement Authorities, 1600–1750" (PDF). International Institute of Social History. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "The Turnpike Road". Dorking Museum. 4 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Crocker 1999, p. 73

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 129

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 70

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, p. 133

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, pp. 165–168

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, p. 62

- ^ a b Heath 2012, p. 11

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 243

- ^ Davies, H.J. (1993). "The Epsom and Leatherhead Railway 1856-59" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead& District Local History Society. 5 (6): 170–172. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, pp. 168–169

- ^ Jackson 1988, pp. 26–27

- ^ Historic England. "Leatherhead Station (Grade II) (1191033)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b Knowles, H.G. (1998). "Leatherhead's railway stations" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead& District Local History Society. 6 (2): 46–52. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Leatherhead by-pass road". The Times. No. 46717. London. 2 April 1934. p. 7.

- ^ "The Whitsun Holiday". The Times. No. 46759. London. 21 May 1934. p. 7.

- ^ Crossland, EA (1993). "The building of Young Street" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History. 5 (6): 160. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Petty, John (5 October 1985). "Cracked M25 link to open". Daily Telegraph. No. 40526. London. p. 36.

- ^ Vardey 1988, p. 98

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 149–152

- ^ Stuttard 1995, pp. 124

- ^ a b Stuttard 1995, pp. 134

- ^ Vardey 1988, pp. 232–234

- ^ a b Vardey 1988, pp. 257–258

- ^ a b Powell, Goff. "Ronson UK, Randalls Road, Leatherhead" (PDF). Leatherhead & District Local History Society. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b Heath & Tarplee 2005, pp. 58–59

- ^ "Independent Living Services". QEF. 14 July 2021 [14 November 2015]. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b Tarplee 2010, pp. 43–48

- ^ "Disability firm to close 43 sites". BBC News. 22 May 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Despair as Remploy factory gets closure notice". Surrey Live. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Our treatment centres". Combat Stress. 2021. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Gibbons, Laurence (15 September 2015). "Leatherhead acquired by Science Group for £1.6M". Food Manufacture. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Forrest, JS (1955). "British Electricity Research Laboratories". Physics Bulletin. 6 (3): 42–52. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/6/3/003.

- ^ Forrest, JS (1965). "Central Electricity Research Laboratories". Physics Bulletin. 16 (9): 337–346. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/16/9/001.

- ^ Weich, Ben (24 November 2015). "Leatherhead Food Research to leave town after 96 years". Surrey Comet. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Martin, Guy (2 July 2013) [11 January 2013]. "Unilever staff move 'good news' for Leatherhead". Get Surrey. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Shakesby, Chloe (30 June 2020). "Hyundai relocates UK headquarters to Leatherhead". Bdaily News. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Vardey 2001, p. 124