Ngoni Kingdom

Kingdom of Ngoni Mzimba | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–present[1] | |||||||||||||

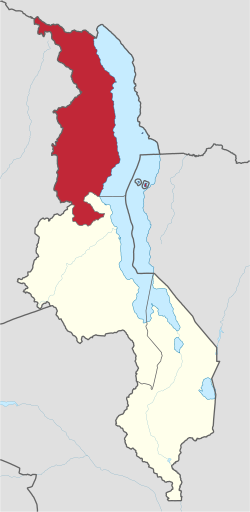

Location of the Ngoni Kingdom, c. 1815 (red) (borders in flux) | |||||||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of the United Kingdom 1857–1891 | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Mzimba; Ekwendeni; Euthini | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Ngoni religion | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 1815–1848 | Zwangendaba Hlatshwayo | ||||||||||||

• 1857 | Gwaza Jele | ||||||||||||

• 1857–1891 | M'mbelwa I | ||||||||||||

• 1896–1915 | Cimtunga | ||||||||||||

• 1928–1959 | M'mbelwa II | ||||||||||||

• 1959–1983 | M'mbelwa III | ||||||||||||

• 1984–2013 | M'mbelwa IV | ||||||||||||

• 2013–present | M'mbelwa V | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Death of Inkosi ya Makosi Zwangendaba Hlatshwayo | 1815 | ||||||||||||

• Accession of Inkosi ya Makosi Gwaza Jele | 1815 | ||||||||||||

• Battle of Ilwani Atonga | 1857 | ||||||||||||

• Ngoni–Tumbuka Battle | 1891 | ||||||||||||

• Battle of Vituzu | 1896 | ||||||||||||

• Tumbuka–Ngoni War | 1897 | ||||||||||||

• British protectorate | 1915 | ||||||||||||

• to Ekwendeni | present[1] | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1815 | 25,900 km2 (10,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1848 | 110,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Cattle | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Malawi | ||||||||||||

The Ngoni Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Ngoni Empire or the Kingdom of Ngoni, is a monarchy[2][3] in Southern Africa[4] that started in 1815 when some of the Nguni of South Africa broke away from the Zulu Kingdom[1] and escaped to Malawi.[5][6][7][8][4]

History

Chaka leadership

The Ngoni kingdom began during the reign of Chaka, the infamous Ngoni king, which marked the beginning of a dark chapter in African history. His brief rule of seven or eight years was characterized by unprecedented bloodshed, displacement, and devastation. The violence and chaos he unleashed had far-reaching consequences, affecting countless tribes and communities. [9][10]

Chaka's brutality

Chaka's brutal campaigns resulted in the deaths of over a million people, either directly or indirectly. Many more were displaced, forced into cannibalism, or left to die in the wilderness. The full extent of the suffering and misery he caused may never be fully known. Despite his reign of terror, Chaka's eventual death in 1828 did not bring an end to the violence. The Ngoni people, who had been united under his rule, began to splinter and migrate, leaving a trail of bloodshed in their wake.[11]

One notable incident during Chaka's reign was his battle against Zwide, a rival chief. Chaka emerged victorious thanks to the treachery of Noluju, a political prisoner who sought revenge against Zwide. Noluju's betrayal led to Zwide's defeat, but ultimately, it also sealed his own fate. He was later killed by Zwide's spies while celebrating his victory in a song, which became a haunting paean and prophecy for the fate of many tribes. Noluju's story serves as a poignant reminder of the cyclical nature of violence and revenge that characterized this dark period in African history.[9]

Zwide leadership

The Ngoni people, though living under Zwide's rule, occasionally rebelled against him. A remarkable story from that time highlights the power of principle and the influence of superstition in their lives. When Zwide, who had been defeated and imprisoned by Zwangendaba, was released and sent back with a gift of cattle, his pride was wounded, and he sought revenge. His mother, Lowawa, tried to reason with him, urging him not to attack the Ngoni, who had shown mercy by releasing him and gifting him cattle. However, Zwide refused to listen.[11]

Determined to stop her son, Lowawa devised a plan to strike fear into the hearts of his soldiers. She entered the cattle-fold, a forbidden area for women, and stood exposed among the soldiers, who were shocked and awed by her bold move. They saw it as an omen, a sign that an ancestral spirit was warning them against going to war. Fearing the consequences, they disbanded, and Zwide's plans for revenge were foiled.[9]

Zwangedaba

As Zwide's power waned, Zwangendaba and other petty chiefs led sections of the tribe in search of new lands, adopting Chaka's methods and seeking to emulate his fame. They attacked the Swazi people, impressing some to join them and capturing many cattle. They then entered Tongaland, settled for a time, and later moved on to attack the Kalanga tribe, instructing them in their warfare methods and gaining power through their additions. Eventually, they arrived at the Zambezi River in June 1825, between Zumbo and Tete.[11]

The Ngoni people's journey, marked by conquest and violence, was shaped by their desire for power and their adoption of Chaka's methods, which had a lasting impact on the region.[11]

The two kingdoms

Gazaland Kingdom

There were also two kingdoms south of the Zambezi, founded by chiefs who fled from Chaka's tyranny around the same time the Ngoni began their wanderings. The first is Gazaland, established by Sotshangane, who fought alongside Zwangendaba against Chaka and later fled. It's likely that his journey northward was marked by violence and bloodshed, as he and his successor Umzila expanded their kingdom, subjugating many small tribes in the process. However, the extent of the suffering and death that resulted is unknown. Umzila's son Gungunhana later succeeded him and became a thorn in the side of the Portuguese, much like the Matabele were to the British.

Mzilikazi Kingdom

The second powerful kingdom that emerged during this time was that of Mzilikazi, who fled from Chaka's tyranny and settled in the northern Transvaal. His name struck fear into the hearts of many, as he subjugated or destroyed every tribe that dared oppose him. Dr. Robert Moffat, a missionary, visited Mzilikazi in 1829 and formed a strong bond with him, which lasted for thirty-nine years until Mzilikazi's death in 1868. Dr. Moffat's accounts of his visits with Mzilikazi offer a fascinating glimpse into the life of this powerful chief, who was both a ruthless warrior and a complex individual. As Dr. Moffat bid farewell to Mzilikazi in 1860, he reflected on their unlikely friendship and the contrast between the Matabele tyrant and the messenger of peace.[9]

Encounter with the Sengas

The Ngoni, who had by now crossed the Zambezi, encountered the Senga tribe and easily subjugated them, incorporating them into their own ranks. The Senga were an easy prey, and the Ngoni initiated them into their weapons and ways of war, resting in the district and depleting its resources.

Encounter with the Tumbukas

Matshulu district

The Ngoni, now bolstered by the addition of the Senga people, continued their northward journey, likely following the Luangwa river watershed. They arrived in the Matshulu district, inhabited by the Tumbuka tribe, who were known for their agricultural prowess. The Tumbuka submitted to the Ngoni, providing for their needs. However, a rift developed within the Ngoni ranks, as Zwangendaba's original followers grew jealous of his favoritism towards the Tonga advisors. The Tumbuka, skilled in witchcraft, fueled these tensions, leading to accusations of witchcraft against the Tonga. Zwangendaba, incited by the Tumbuka, ordered the destruction of entire villages, massacring nearly all the Tonga. This period, known as the "killing time," left a lasting impact on the people.

Maphupho district

As the Ngoni continued northward, they arrived in the Maphupho district, inhabited by the Sukuma. It was here that Zwangendaba died, leading to disruptions within the tribe. The Ngoni then splintered into sections, with some heading northward on the west side of Tanganyika, while others, led by Ntutu, went eastward, carrying war and bloodshed across a vast region. The Watuta section, described by Stanley as a fierce and warlike race, separated from the main body and continued their campaign of conquest. Their exploits, marked by violence and plunder, left a lasting impact on the region. The wave of bloodshed unleashed by Chaka's initial conquests continued to spread, a testament to the enduring legacy of his brutal reign.

Urundi and Uhha

The Ngoni, still unsatisfied with their conquests, launched attacks on Urundi and Uhha, but faced formidable foes in the Wahha and other intra-lake region tribes. Despite their setbacks, they continued their destructive path through Uvinza, Unyamwezi, Uzumbwa, Utambara, Urangwa, Uyofu, and Uzinja, eventually reaching the Victoria Nyanza, where they rested for several years. They later returned and settled in Ugomba, between Uhha and Unyamwezi, and became known as the Ngoni of Nyamwezi.

Mmbelwa

The third section of the Ngoni, led by Mmbelwa, included his brothers Mthwalo, Mpherembe, Mpezeni, and Mabilabo. They moved eastward to Tshidhlodhlo, where they engaged in a fierce battle with the Gwangwara, who emerged victorious and drove them southward. The Gwangwara eventually settled on the east side of Lake Nyasa and extended their reach into Yaoland and Masasi. Mmbelwa's division suffered a disruption, with Mpherembe and Mpezeni breaking away. Mpherembe attacked the Bemba south of Tanganyika, while Mpezeni settled west of Lake Nyasa's southern extremity. Chiwere, a headman, established his own following west of Nkhotakota. Mmbelwa's division eventually settled in Henga, subjugated the Henga section of the Tumbuka tribe, and entered the Tumbuka country proper. They continued to occupy the valleys of the Lunyangwa, Kasitu, and Rukuru rivers, governing the Tumbuka and Tonga tribes and only recently abandoning their predatory ways.[11]

Kings

M'mbelwa I

Mbelwa I was the son of Zwangendaba who married a Swazi woman called Munene. He was born at Mabili in Malawi around 1840.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Minister asks Inkosi Mbelwa to resolve Zulu chieftainship wrangle – Malawi Nyasa Times – News from Malawi about Malawi". www.nyasatimes.com. 2017-09-19. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ "Ngoni chief urges men to cut their foreskins to reduce HIV risk – Malawi Nyasa Times – News from Malawi about Malawi". www.nyasatimes.com. 2018-12-02. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ "Powerful Ngoni chief tells CCAP church off over beer, polygamy: 'Ngonis will continue to booze and marry' – Malawi Nyasa Times – News from Malawi about Malawi". www.nyasatimes.com. 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ a b c "M'mbelwa Kingdom, Jele Ngoni of Malawi – THE AFRICAN ROYAL FAMILIES". theafricanroyalfamilies.com. 2024-02-12. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Nyirenda, Jamu (December 2021). ""Inkosi Yetu Ngu Kamuzu Yedwa" (Our Only King Is Kamuzu): The M'mbelwa Ngoni's relations with Hastings Kamuzu Banda in Malawi from 1964 to 1994". New Contree. 2021 (87): 107–121. doi:10.54146/newcontree/2021/87/06. ISSN 0379-9867.

- ^ "M'Mbelwa". The Ngoni People of Africa. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Thompson, T. Jack (1995-01-01), "NGONI ORIGINS", Christianity in Northern Malaŵi, Brill, pp. 1–29, ISBN 978-90-04-31996-7, retrieved 2024-02-28

- ^ "Ngoni king M'mbelwa V strips off Mahobe chieftaincy for marrying minor - Malawi Nyasa Times - News from Malawi about Malawi". www.nyasatimes.com. 2020-08-24. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ a b c d "M'mbelwa Kingdom, Jele Ngoni of Malawi - THE AFRICAN ROYAL FAMILIES". theafricanroyalfamilies.com. 2024-03-15. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ^ Mbatha, Mthandeni Patric; Cebekhulu, Mxolisi Bongumusa PraseGod (2022-12-30). "The concepts of 'Zulu tribe' and 'Zulu nation' and their use towards political aspirations in South Africa". ScienceRise (6): 32–41. doi:10.21303/2313-8416.2022.002869. ISSN 2313-8416.

- ^ a b c d e https://www.sundaynews.co.zw/a-historical-background-of-the-ngoni-of-zwangendaba/

Further reading

- Bryant, Alfred T. (1964). A History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Tribes. Cape Town: C. Struik. p. 157.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). pp. 1050–1055.

External links

- People of Africa, Zulu marriage explained

- An article on Piet Retief, including his interactions with Dingane

- History section of the official page for the Zululand region