Willie Nelson

Willie Nelson | |

|---|---|

Nelson in 2007 | |

| Born | Willie Hugh Nelson April 29, 1933 Abbott, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1956–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8, including Paula and Lukas |

| Relatives | Bobbie Nelson (sister) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | The Highwaymen |

| Website | www |

Willie Hugh Nelson (born April 29, 1933) is an American country singer, guitarist and songwriter. He was one of the main figures of the outlaw country subgenre that developed in the late 1960s as a reaction to the conservative restrictions of the Nashville sound. The critical success of his album Shotgun Willie (1973), combined with the critical and commercial success of Red Headed Stranger (1975) and Stardust (1978), made Nelson one of the most recognized artists in country music. Nelson has acted in over 30 films, co-authored several books, and has been involved in activism for the use of biofuels and the legalization of marijuana.

Nelson wrote his first song at age seven and joined his first band at ten. During high school, he toured locally with the Bohemian Polka as their lead singer and guitar player. After graduating from high school in 1950, he joined the U.S. Air Force but was later discharged due to back problems. After his return, Nelson attended Baylor University for two years but dropped out because he was succeeding in music. He worked as a disc jockey at radio stations in his native Texas, and at several radio stations in the Pacific Northwest, all the while working as a singer and songwriter throughout the late 1950s. During that time, he wrote songs that would become country standards, including "Funny How Time Slips Away", "Hello Walls", "Pretty Paper", and "Crazy". In 1960 he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, and later signed a publishing contract with Pamper Music which allowed him to join Ray Price's band as a bassist. In 1962, he recorded his first album, ...And Then I Wrote. Due to this success, Nelson signed in 1964 with RCA Victor and joined the Grand Ole Opry the following year. After mid-chart hits in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, Nelson grew weary of the corporate Nashville music scene, and in 1972 he moved to Austin, Texas. The ongoing music scene of Austin motivated Nelson to return to performing, appearing frequently at the Armadillo World Headquarters.

In 1973, after signing with Atlantic Records, Nelson turned to outlaw country, including albums such as Shotgun Willie and Phases and Stages. In 1975, he switched to Columbia Records, where he recorded the critically acclaimed album Red Headed Stranger. The same year, he recorded another outlaw country album, Wanted! The Outlaws, along with Waylon Jennings, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser. During the mid-1980s, while creating hit albums like Honeysuckle Rose and recording hit songs like "On the Road Again", "To All the Girls I've Loved Before", and "Pancho and Lefty", he joined the country supergroup The Highwaymen, along with fellow singers Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. In 1985, he helped organize the first Farm Aid concert to benefit American farmers; the concerts have been held annually ever since and Nelson has been a fixture, appearing at every one.

In 1990, Nelson's assets were seized by the Internal Revenue Service, which claimed that he owed $32 million. The difficulty of paying his outstanding debt was aggravated by weak investments he had made during the 1980s. In 1992, Nelson released The IRS Tapes: Who'll Buy My Memories?; the profits of the double album—destined to the IRS—and the auction of Nelson's assets cleared his debt. During the 1990s and 2000s, Nelson continued touring extensively and released albums every year. Reviews ranged from positive to mixed. He explored genres such as reggae, blues, jazz, and folk.

Nelson made his first movie appearance in the 1979 film The Electric Horseman, followed by other appearances in movies and on television. Nelson is a major liberal activist and the co-chair of the advisory board of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), which is in favor of marijuana legalization. On the environmental front, Nelson owns the biodiesel brand Willie Nelson Biodiesel, whose product is made from vegetable oil. Nelson is also the honorary chairman of the advisory board of the Texas Music Project, the official music charity of the state of Texas.

Early life

Nelson was born in Abbott, Texas, on April 29, 1933,[1] the son of Ira Doyle Nelson and Myrle Marie (née Greenhaw).[2] His birthday was incorrectly recorded by Dr. F. D. Sims as April 30.[1] He was named Willie by his cousin Mildred, who also chose Hugh as his middle name, in honor of her recently deceased younger brother.[1] Nelson traces his genealogy to the American Revolutionary War, in which his ancestor John Nelson served as a major.[3] His parents moved to Texas from Arkansas in 1929 to look for work. His grandfather, William, worked as a blacksmith, while his father worked as a mechanic.[4] His mother left soon after he was born,[5] and his father remarried and also moved away, leaving Nelson and his sister Bobbie to be raised by their grandparents, who taught singing back in Arkansas and started their grandchildren in music.[6][7] Nelson's grandfather bought him a guitar when he was six, and taught him a few chords,[4] and Nelson sang gospel songs in the local church alongside Bobbie.[8] He wrote his first song at age seven,[9] and when he was nine, he played guitar for local band Bohemian Polka.[10] During the summer, the family picked cotton alongside other Abbott residents.[11] Nelson disliked picking cotton, so he earned money by singing in dance halls, taverns, and honky tonks from age 13, which he continued through high school.[12] His musical influences were Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price, Ernest Tubb, Hank Snow, Django Reinhardt, Frank Sinatra, and Louis Armstrong.[13][14][15]

Nelson attended Abbott High School, where he was a halfback on the football team, guard on the basketball team, and shortstop in baseball. He also raised pigs with the Future Farmers of America.[2] While still at school, he sang and played guitar in The Texans, a band formed by his sister's husband, Bud Fletcher.[10] The band played in honky-tonks, and also had a Sunday morning spot at KHBR in Hillsboro, Texas. Meanwhile, Nelson had a short stint as a relief phone operator in Abbott, followed by a job as a tree trimmer for the local electric company, as well as a pawn shop employee.[16] After leaving school in 1950, he joined the U.S. Air Force; he served for nine months before being medically discharged because of issues with his back.[17] Upon his return in 1952, he married Martha Matthews, and from 1954 to 1956 studied agriculture at Baylor University, where he joined the Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity, until dropping out to pursue a career in music.[18] He worked as a nightclub bouncer, autohouse partsman, saddle maker, and tree trimmer again. He later joined Johnny Bush's band.

Nelson moved with his family to Pleasanton, Texas, where he auditioned for a job as a DJ at KBOP. The owner of the station, Dr. Ben Parker, gave Nelson the job despite his lack of experience working on radio.[16] With the equipment of the station, Nelson made his first two recordings in 1955: "The Storm Has Just Begun" and "When I've Sung My Last Hillbilly Song". He recorded the tracks on used tapes, and sent the demos to the local label SARG Records, which rejected them.[19] He then had stints working for KDNT in Denton, KCUL, and KCNC in Fort Worth, where he hosted The Western Express, taught Sunday school, and played in nightclubs. He then decided to move to San Diego but, when he was unable to find a job there, he hitchhiked to Portland, Oregon, where his mother lived.[16] When nobody picked him up, he ended up sleeping in a ditch[20] before hopping a freight train bound for Eugene. A truck driver drove him to a bus station and loaned him $10 for a ticket to reach Portland.[21]

Music career

Beginnings (1956–1971)

Nelson was hired by KVAN in Vancouver, Washington, and appeared frequently on a television show.[16][22] He made his first record in 1956, "No Place for Me", that included Leon Payne's "Lumberjack" on the B-side.[23] The recording failed.[24] Nelson continued working as a radio announcer and singing in Vancouver clubs.[25] He made several appearances in a Colorado nightclub, later moving to Springfield, Missouri. After failing to land a spot on the Ozark Jubilee, he started to work as a dishwasher. Unhappy with his job, he moved back to Texas. After a short time in Waco, he settled in Fort Worth, and quit the music business for a year.[16] He sold bibles and vacuum cleaners door-to-door,[26] and eventually became a sales manager for the Encyclopedia Americana.[27]

After his son Billy was born in 1958, the family moved to Houston, Texas. On the way, Nelson stopped by the Esquire Ballroom to sell his original songs to house band singer Larry Butler. Butler refused to purchase the song "Mr. Record Man" for $10, instead giving Nelson a $50 loan to rent an apartment and a six-night job singing in the club.[28] Nelson rented the apartment near Houston in Pasadena, Texas, where he also worked at the radio station as the sign-on disc jockey. During this time, he recorded two singles for Pappy Daily on D Records[29] "Man With the Blues"/"The Storm Has Just Begun" and "What a Way to Live"/"Misery Mansion".[30] Nelson then was hired by guitar instructor Paul Buskirk to work as an instructor in his school. He sold "Family Bible" to Buskirk for $50 and "Night Life" for $150.[31] "Family Bible" turned into a hit for Claude Gray in 1960.[32]

Nelson moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1960, but was unable to find a label to sign him. During this period he often spent time at Tootsie's Orchid Lounge, a bar near the Grand Ole Opry frequented by the show's stars and other singers and songwriters.[33] There Nelson met Hank Cochran, a songwriter who worked for the publishing company Pamper Music, owned by Ray Price and Hal Smith. Cochran heard Nelson during a jam session with Buddy Emmons and Jimmy Day. Cochran had just earned a raise of $50 a week, but convinced Smith to pay Nelson the money instead to sign him to Pamper Music. On hearing Nelson sing "Hello Walls" at Tootsie's, Faron Young decided to record it.[34] After Ray Price recorded Nelson's "Night Life", and his previous bassist Johnny Paycheck quit, Nelson joined Price's touring band as a bass player. While playing with Price and the Cherokee Cowboys, his songs became hits for other artists, including "Funny How Time Slips Away" (Billy Walker), "Pretty Paper" (Roy Orbison), and, most famously, "Crazy" by Patsy Cline.[25] Nelson and Cochran also met Cline's husband, Charlie Dick at Tootsie's. Dick liked a song of Nelson's he heard on the bar's jukebox. Nelson played him a demo tape of "Crazy". Later that night Dick played the tape for Cline, who decided to record it.[6] "Crazy" became the biggest jukebox hit of all time.[35]

Nelson signed with Liberty Records and was recording by August 1961 at the Bradley Studios in Nashville. His first two successful singles as an artist were released by the next year, including "Willingly" (a duet with his soon-to-be second wife, Shirley Collie, which became his first charting single and first Top Ten at No. 10) and "Touch Me" (his second Top Ten, stalling at No. 7).[36] Nelson's tenure at Liberty yielded his first album entitled ...And Then I Wrote, released in September 1962.[37] In 1963 Collie and Nelson were married in Las Vegas. He then worked on the west coast offices of Pamper Records, in Pico Rivera, California. Since the job did not allow him the time to play music of his own, he left it and bought a ranch in Ridgetop, Tennessee, outside of Nashville.[27] Fred Foster of Monument Records signed Nelson in early 1964, but only one single was released: "I Never Cared For You".[38]

By the fall of 1964, Nelson had moved to RCA Victor at the behest of Chet Atkins, signing a contract for $10,000 per year.[39] Country Willie – His Own Songs became Nelson's first RCA Victor album, recorded in April 1965. That same year he joined the Grand Ole Opry,[40] and he met and became friends with Waylon Jennings after watching one of his shows in Phoenix, Arizona.[41] In 1967, he formed his backing band "The Record Men", featuring Johnny Bush, Jimmy Day, Paul English and David Zettner.[42] During his first few years on RCA Victor, Nelson had no significant hits, but from November 1966 through March 1969, his singles reached the Top 25 in a consistent manner. "One in a Row" (#19, 1966), "The Party's Over" (#24 during a 16-week chart run in 1967), and his cover of Morecambe & Wise's "Bring Me Sunshine" (#13, March 1969) were Nelson's best-selling records during his time with RCA.[24]

By 1970, most of Nelson's songwriting royalties were invested in tours that did not produce significant profits. In addition to the problems in his career, Nelson divorced Shirley Collie in 1970. In December, his ranch in Ridgetop, Tennessee, burned down. He interpreted the incident as a signal for a change. He moved to a ranch near Bandera, Texas, and married Connie Koepke. In early 1971 his single "I'm a Memory" reached the top 30.[43] After he recorded his final RCA single, "Mountain Dew" (backed with "Phases, Stages, Circles, Cycles and Scenes"), in late April 1972, RCA requested that Nelson renew his contract ahead of schedule, with the implication that RCA would not release his latest recordings if he did not.[44] Due to the failure of his albums, and particularly frustrated by the reception of Yesterday's Wine, although his contract was not over, Nelson decided to retire from music.[45]

Outlaw country and success (1972–1989)

Nelson moved to Austin, Texas, where the burgeoning hippie music scene (see Armadillo World Headquarters) rejuvenated the singer. His popularity in Austin soared as he played his own brand of country music marked by country, folk and jazz influences.[46] In March, he performed on the final day of the Dripping Springs Reunion, a three-day country music festival aimed by its producers to be an annual event. Despite the failure to reach the expected attendance, the concept of the festival inspired Nelson to create the Fourth of July Picnic, his own annual event, starting the following year.[47]

Nelson decided to return to the recording business; he signed Neil Reshen as his manager to negotiate with RCA, who got the label to agree to end his contract upon repayment of $14,000.[44] Reshen eventually signed Nelson to Atlantic Records for $25,000 per year, where he became the label's first country artist.[48] He formed his backing band, The Family,[49] and, by February 1973, he was recording his acclaimed Shotgun Willie at Atlantic Studios in New York City.[50]

Shotgun Willie, released in May 1973, earned excellent reviews but did not sell well. The album led Nelson to a new style, later stating that Shotgun Willie had "cleared his throat".[51] His next release, Phases and Stages, released in 1974, was a concept album about a couple's divorce, inspired by his own experience. Side one of the record is from the viewpoint of the woman, and side two is from the viewpoint of the man.[52] The album included the hit single "Bloody Mary Morning".[53] The same year, he produced and starred in the pilot episode of PBS' Austin City Limits.[54]

Nelson then moved to Columbia Records, where he signed a contract that gave him complete creative control, made possible by the critical and commercial success of his previous albums.[55] The result was the critically acclaimed and massively popular 1975 concept album Red Headed Stranger. Although Columbia was reluctant to release an album with primarily a guitar and piano for accompaniment, Nelson and Waylon Jennings insisted. The album included a cover of Fred Rose's 1945 song "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain", that had been released as a single previous to the album, and became Nelson's first number one hit as a singer.[56] Throughout his 1975 tour, Nelson raised funds for PBS-affiliated stations across the south promoting Austin City Limits. The pilot was aired first on those stations, later being released nationwide. The positive reception of the show prompted PBS to order ten episodes for 1976, formally launching the show.[57]

As Jennings was also achieving success in country music in the early 1970s, the pair were combined into a genre called outlaw country, since it did not conform to Nashville standards.[58] The album Wanted! The Outlaws in 1976 with Jessi Colter and Tompall Glaser cemented the pair's outlaw image and became country music's first platinum album.[59] Later that year Nelson released The Sound in Your Mind (certified gold in 1978 and platinum in 2001)[60] and his first gospel album Troublemaker[61] (certified gold in 1986).[62]

In the summer of 1977, Nelson discovered that Reshen had been filing tax extensions and not paying the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) since he took over as his manager.[63] In June, a package containing cocaine was sent from Reshen's office in New York to Jennings in Nashville.[64] The package was followed by the DEA, and Jennings was arrested. The charges were later dropped, since Reshen's assistant, Mark Rothbaum, stepped in and took the charges. Rothbaum was sentenced to serve time in jail. Impressed by his attitude, Nelson fired Reshen and hired Rothbaum as his manager.[63] In 1978, Nelson released two more platinum albums. One, Waylon & Willie, was a collaboration with Jennings that included "Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys", a hit single written and performed by Ed Bruce.[65] Though observers predicted that Stardust would ruin his career, it went platinum the same year.[66] Nelson continued to top the charts with hit songs during the late 1970s, including "Good Hearted Woman", "Remember Me",[67] "If You've Got the Money I've Got the Time", and "Uncloudy Day".[68]

During the 1980s, Nelson recorded a series of hit singles including "Midnight Rider", a 1980 cover of the Allman Brothers song which Nelson recorded for The Electric Horseman,[69] the soundtrack "On the Road Again" from the movie Honeysuckle Rose, and a duet with Julio Iglesias titled "To All the Girls I've Loved Before".[70]

In 1982, Pancho & Lefty, a duet album with Merle Haggard produced by Chips Moman, was released.[71] During the recording sessions of Pancho and Lefty, Johnny Christopher, a session guitarist and the co-writer of "Always on My Mind", tried to pitch the song to an uninterested Haggard. Nelson, who was unaware of Elvis Presley's version of the song, asked him to record it. Produced by Moman, the single of the song was released, as well as the album of the same name. The single topped Billboard's Hot Country Singles, while it reached number five on the Billboard Hot 100. The release won three awards during the 25th Annual Grammy Awards: Song of the Year, Best Country Song and Best Male Country Vocal Performance. The single was certified platinum, while the album was certified quadruple-platinum and later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2008.[72]

Meanwhile, two collaborations with Waylon Jennings were released: WWII in 1982,[73] and Take it to the Limit in 1983. In the mid-1980s, Nelson, Jennings, Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash formed The Highwaymen, a supergroup who achieved platinum record sales and toured the world.[74] Meanwhile, Nelson became more involved with charity work, such as singing on We are the World in 1984.[75] In 1985, Nelson had another success with Half Nelson, a compilation album of duets with a range of artists such as Ray Charles and Neil Young.[76] In 1980, Nelson performed on the south lawn of the White House. The concert of September 13 featured First Lady Rosalynn Carter and Nelson in a duet of Ray Wylie Hubbard's "Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother". Nelson frequently visited the White House, where, according to the biography by Joe Nick Patoski, Willie Nelson: An Epic Life, he smoked marijuana on the White House roof.[77]

Later career (1990s–2000s)

In 1996, Nelson re-recorded the tracks "Hello Walls" with the band the Reverend Horton Heat, and "Bloody Mary Morning" with the Supersuckers, for Twisted Willie, a tribute album featuring rock versions of Nelson's songs performed by artists such as Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Cantrell, Mark Lanegan, L7, the Presidents of the United States of America, and Jello Biafra, among others.[78] Proceeds from the sale of the record went to Nelson's Farm Aid.[79]

During the 1990s and 2000s, Nelson toured continuously, recording several albums including 1998's critically acclaimed Teatro,[80] and performed and recorded with other acts including Phish,[81] Johnny Cash,[82] and Toby Keith. His duet with Keith, "Beer for My Horses", was released as a single and topped the Billboard Hot Country Songs charts for six consecutive weeks in 2003,[83] while the accompanying video won an award for "Best Video" at the 2004 Academy of Country Music Awards.[84] A USA Network television special celebrated Nelson's 70th birthday,[85] and Nelson released The Essential Willie Nelson as part of the celebration. Nelson also appeared on Ringo Starr's 2003 album, Ringo Rama, as a guest vocal on "Write One for Me".[86]

Nelson was featured on the album True Love by Toots and the Maytals, which won the Grammy Award in 2004 for Best Reggae Album, and showcased many notable musicians including Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Trey Anastasio, Gwen Stefani, and Keith Richards.[87] In the following year of 2005, Nelson released a reggae album entitled Countryman which featured Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals on the song "I'm a Worried Man".[88]

Nelson headlined the 2005 Tsunami Relief Austin to Asia concert to benefit the victims of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, which raised an estimated $75,000 for UNICEF.[89] Also in 2005, a live performance of the Johnny Cash song "Busted" with Ray Charles was released on Charles' duets album Genius & Friends. Nelson's 2007 performance with jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis at the Lincoln Center, was released as the live album Two Men with the Blues in 2008; reaching number one in Billboard's Top Jazz Albums and number twenty on the Billboard 200.[90] The same year, Nelson recorded his first album with Buddy Cannon as the producer, Moment of Forever. Cannon acquainted Nelson earlier, during the production of his collaboration with Kenny Chesney on the duet "That Lucky Old Sun", for Chesney's album of the same name.[91] In 2009 Nelson and Marsalis joined with Norah Jones in a tribute concert to Ray Charles, which resulted in the Here We Go Again: Celebrating the Genius of Ray Charles album, released in 2011.[92]

2010s

In 2010, Nelson released Country Music, a compilation of standards produced by T-Bone Burnett.[93] The album peaked number four in Billboard's Top Country Albums, and twenty on the Billboard 200.[94] It was nominated for Best Americana Album at the 2011 Grammy Awards.[95] In 2011 Nelson participated in the concert Kokua For Japan, a fund raising event for the victims of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan which raised $1.6 million.[96]

In February 2012, Legacy Recordings signed a deal with Nelson that included the release of new material, as well as past releases that would be selected and complemented with outtakes and other material selected by him.[97] With the new deal, Buddy Cannon returned to produce the recordings of Nelson. After selecting the material and the sound of the tunes with the singer, Cannon's work method consisted in the recording of the tracks with studio musicians, with the takes later completed on a separate session by Nelson with his guitar. Cannon's association to Nelson also extended to songwriting, with singer and producer composing the lyrics by exchanging text messages.[91]

Nelson's first release for the Legacy Recordings was Heroes, that included guest appearances by his sons Lukas and Micah of the band Insects vs Robots, Ray Price, Merle Haggard, Snoop Dogg, Kris Kristofferson, Jamey Johnson, Billy Joe Shaver and Sheryl Crow. The album reached number four on Billboard's Top Country Albums.[98] His 2013 release To All the Girls..., a collection of duets with all female partners, featured among others Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn, Rosanne Cash, Sheryl Crow, Mavis Staples, Norah Jones, Emmylou Harris, Carrie Underwood and Miranda Lambert.[99] The album entered Billboard's Top Country Albums at number two, marking his highest position on the chart since the release of his 1989 A Horse Called Music, and extending his record to a total of forty-six top ten albums on the country charts. Nelson scored as well his second top ten album on the Billboard 200, with the release entering at number nine.[100]

Nelson’s following release was Band of Brothers, in 2014, the first Nelson album to feature the most newly self-penned songs since 1996's Spirit. Upon its release, it topped Billboard's Top Country albums chart, the first time since 1986's The Promiseland, the last Nelson album to top it. The release reached number five on the Billboard 200, Nelson's highest position on the chart since 1982's Always on My Mind.[101] In December 2014, a duet with Rhonda Vincent, "Only Me", topped Bluegrass Unlimited's National Airplay chart.[102] In June 2015, his collaboration with Haggard Django and Jimmie topped Billboard's Top Country albums chart and reached number seven on the Billboard 200.

In 2017, Nelson released God's Problem Child. The release, consisting mostly of Nelson originals co-written with Cannon, entered the Top country albums at number one, while it reached number ten on the Billboard 200.[103]

In 2018, Nelson sang a song written by Daniel Lanois called "Cruel World" for the soundtrack of Rockstar Games's action-adventure video game Red Dead Redemption 2.[104] Lanois wrote the song especially for Nelson. When a hurricane prevented Nelson from recording the song, the production team sent the track to Josh Homme in the hopes that he could record it in time for the game's release. Nelson was ultimately able to record the song in time in Los Angeles;[105] the team considered combining the two versions into a duet, but ultimately included both versions in the game.[106] Also in 2018, Nelson was one of several artists on Restoration, a cover album containing various country renditions of songs originally by Elton John, on which he performed "Border Song".[107] His 2019 release Ride Me Back Home charted at number two on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart.[108] For the title-track, Nelson received the Grammy Award for Best Country Solo Performance.[109]

2020s

Following the U.S. coronavirus pandemic lockdowns that began in March 2020, Nelson livestreamed a series of benefit concerts. The first two raised $700,000 for people who had suffered financial loss due to effects on the U.S. economy.[110] The third, which was held on April 20, 2020, was a variety show titled Come and Toke It.[111] Some of the content was cannabis-themed, and some of the proceeds will be used to support The Last Prisoner Project, a restorative justice program relating to persons convicted of cannabis related crimes.[112][113][114] The same year, Nelson was approached by Karen O of The Yeah Yeah Yeahs to collaborate. They chose to do a cover of David Bowie and Queen's Under Pressure.[115]

For his releases of The Willie Nelson Family (2021) and A Beautiful Time (2022), Nelson received four nominations for the 65th Annual Grammy Awards winning in two categories: Best Country Solo Performance and Best Country Album.[116][117] In December 2022, Mark Rothbaum announced the release of a five-part documentary entitled Willie Nelson and Family released at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.[116] In 2023, Nelson performed at two concerts at the Hollywood Bowl celebrating his 90th birthday[118] and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[119]

In 2024, Nelson was featured in the "SMOKE HOUR ★ WILLIE NELSON" and "SMOKE HOUR II" interludes of Beyoncé's COWBOY CARTER album, the second album in her trilogy project.[120]

Other ventures

Nelson's acting debut was in the 1979 film The Electric Horseman, followed by appearances in Honeysuckle Rose, Thief, and Barbarosa. He played the role of Red Loon in Coming Out of the Ice in 1982 and starred in Songwriter two years later. He portrayed the lead role in the 1986 film version of his album Red Headed Stranger.[121] Other movies that Nelson acted in include Wag the Dog, Gone Fishin' (as Billy 'Catch' Pooler), the 1986 television movie Stagecoach (with Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson), Half Baked, Beerfest, The Dukes of Hazzard, Surfer, Dude and Swing Vote. He has also made guest appearances on Miami Vice (1986's "El Viejo" episode); Delta; Nash Bridges; The Simpsons; Monk; Adventures in Wonderland; Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman; King of the Hill; The Colbert Report; Swing Vote; and Space Ghost Coast to Coast.[122]

In 1988 his first book, Willie: An Autobiography, was published.[123] The Facts of Life: And Other Dirty Jokes, a personal recollection of tour and musical stories from his career, combined with song lyrics, followed in 2002. In 2005 he co-authored Farm Aid: A Song for America, a commemorative book about the twentieth anniversary of the foundation of Farm Aid.[124] His third book, co-authored with long-time friend Turk Pipkin, The Tao of Willie: A Guide to the Happiness in Your Heart, was published in 2006.[125] In 2007 a book advocating the use of bio-diesel and the reduction of gas emissions, On The Clean Road Again: Biodiesel and The Future of the Family Farm, was published.[4] His next book, A Tale Out of Luck, published in 2008 and co-authored by Mike Blakely, was Nelson's first fictional book.[126] In 2012, it was announced the release of a new autobiography by Nelson, Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die: Musings from the Road. Released on November 13, it was named after the song from his album Heroes. The book contained further biographical details, as well as family pictures and stories about Nelson's political views, as well as his advocation for marijuana. The artwork of the book was designed by Nelson's son, Micah, and the foreword written by Kinky Friedman.[127] In 2015, the publication of a second Nelson autobiography entitled It's a Long Story: My Life co-authored with David Ritz, the book was published on May 5, 2015.[128] Pretty Paper, another collaboration with Ritz was published the following year.[129]

In 2002, Nelson became the official spokesman of the Texas Roadhouse, a chain of steakhouses. Nelson heavily promoted the chain and appeared on a special on Food Network. The chain installed Willie's Corner, a section dedicated to him and decked out with Willie memorabilia, at several locations.[130] In 2004, Nelson and his wife Annie became partners with Bob and Kelly King in the building of two Pacific Bio-diesel plants, one in Salem, Oregon, and the other at Carl's Corner, Texas (the Texas plant was founded by Carl Cornelius, a longtime Nelson friend and the eponym for Carl's Corner). In 2005, Nelson and several other business partners formed Willie Nelson Biodiesel ("Bio-Willie"), a company that was marketing bio-diesel bio-fuel to truck stops.[131] The fuel was made from vegetable oil (mainly soybean oil), and can be burned without modification in diesel engines.[132] Nelson registered his company with Earth Biofuels and he became a board member. In 2007, Nelson forfeited six million shares of the company as he left the board.[133] By 2008, he reopened Willie's Place, a truck stop in Carl's Corner, Texas. The U.S. Bankruptcy Court allowed Nelson to invest in it. The establishment had about 80 employees,[134] and was used as a concert hall with a bar and a 1,000 square feet (93 m2) dance floor.[135] Willie's Place also featured BioWillie pumps. At the time, the government of the United States offered a one dollar tax credit to producers of biodiesel. As the competition grew, the tax credit was discontinued while the prices of fossil fuels continued to drop. Nelson and his partners defaulted the $4,75 million loan they took for the construction of Willie's Place. Nelson then paid $35,000 back, while a judge later rejected the request of his creditors to receive more money from him. TravelCenters of America bought Willie's Place during its foreclosure in 2011. The BioWillie plant was then put on the market for sale. Nelson kept the trademark for BioWillie, which is sold in the islands of Maui and Hawaii. Meanwhile, Nelson owns shares of Big Island Biodiesel in Hawaii and SeQuential-Pacific Biodiesel in Oregon.[133]

In 2010, Nelson founded with the collaboration of producers and filmmakers Luck Films, a company dedicated to produce feature films, documentaries and concerts.[136] The next year, he created the Willie's Roadhouse show which aired on channel 56 of SiriusXM radio. The channel was a result of the merger of his two other channels The Roadhouse and Willie's Place.[137] In November 2014, it was announced that Nelson would be the host of the television series Inside Arlyn, shot at Arlyn Studio in Austin, Texas. The thirteen-episode first season would feature artists being interviewed by Nelson and Dan Rather, followed by a performance. The series concept received attention from cable channels that requested to see the pilot episode.[138] Following the legalization of marijuana in different states, Nelson announced in 2015 through spokesman Michael Bowman the establishment of his own marijuana brand, Willie's Reserve. Plans to open chain stores in the states where marijuana was legalized were announced, to be expanded state-to-state if marijuana legalization is further expanded. Bowman called the brand "a culmination of (Nelson's) vision, and his whole life".[139]

In 2017, Nelson appeared as himself in Woody Harrelson's live film, Lost in London.[140] In June 2017, he appeared alongside Merle Haggard in the documentary The American Epic Sessions directed by Bernard MacMahon. They performed a song Haggard had composed for the film, "The Only Man Wilder Than Me",[141][142] and Bob Wills's classic "Old Fashioned Love",[142] which they recorded live direct to disc on the first electrical sound recording system from the 1920s.[143] It was the last filmed performance of the pair. Rolling Stone commented that "in the final performance of Sessions, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard perform the duet 'The Only Man Wilder Than Me.' Haggard has a look of complete joy on his face throughout the session in the old-timey recording setup once used by his musical heroes."[144]

Music style

Nelson uses a variety of music styles to create his own distinctive blend of country music, a hybrid of jazz, pop, blues, rock and folk.[145] His "unique sound", which uses a "relaxed, behind-the-beat singing style and gut-string guitar"[146] and his "nasal voice and jazzy, off-center phrasing",[145] has been responsible for his wide appeal, and has made him a "vital icon in country music", influencing the "new country, new traditionalist, and alternative country movements of the 1980s and 1990s".[145]

Guitars

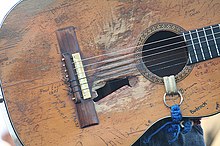

In 1969, the Baldwin company gave Nelson an amplifier and guitar with their "Prismatone" pickup. During a show in Helotes, Texas, Nelson left the guitar on the floor of the stage, and it was later stepped on by a drunk man.[147] He sent it to be repaired in Nashville by Shot Jackson, who told Nelson that the damage was too great. Jackson offered him a Martin N-20 classical guitar, and, at Nelson's request, moved the pickup to the Martin. Nelson purchased the guitar unseen for $750 and named it after Roy Rogers' horse "Trigger".[148] The next year Nelson rescued the guitar from his burning ranch.[149][150]

Constant strumming with a guitar pick over the decades has worn a large sweeping hole into the guitar's body near the sound hole—the N-20 has no pickguard since classical guitars are meant to be played fingerstyle instead of with picks.[35] Its soundboard has been signed by over a hundred of Nelson's friends and associates, ranging from fellow musicians to lawyers and football coaches.[148] The first signature on the guitar was Leon Russell's, who asked Nelson initially to sign his guitar. When Nelson was about to sign it with a marker, Russell requested him to scratch it instead, explaining that the guitar would be more valuable in the future. Interested in the concept, Nelson requested Russell to also sign his guitar.[147] In 1991, during his process with the IRS, Nelson was worried that Trigger could be auctioned off, stating: "When Trigger goes, I'll quit". He asked his daughter, Lana, to take the guitar from the studio before any IRS agent arrived there, and then deliver it to him in Maui.[150] Nelson then concealed the guitar in his manager's house until his debt was paid off in 1993.[148]

Activism

Nelson is active in a number of issues. Along with Neil Young and John Mellencamp, he set up Farm Aid in 1985 to assist and increase awareness of the importance of family farms, after Bob Dylan's comments during the Live Aid concert that he hoped some of the money would help American farmers in danger of losing their farms through mortgage debt.[151] The first concert included Dylan, Billy Joel, B.B. King, Roy Orbison, and Neil Young among many others, and raised over $9 million for America's family farmers.[152] Besides organizing and performing in the annual concerts, Nelson is the president of the board of Farm Aid.[153]

Nelson is a co-chair of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) advisory board.[154] He has worked with NORML for years, promoting marijuana legalization. In 2005 Nelson and his family hosted the first annual "Willie Nelson & NORML Benefit Golf Tournament", leading to a cover appearance and inside interview in the January 2008 issue of High Times magazine.[155] After his arrest for possession of marijuana in 2010, Nelson created the TeaPot party under the motto "Tax it, regulate it and legalize it!"[156]

In 2001, following the September 11 attacks, Nelson participated in the benefit telethon America: A Tribute to Heroes, leading the rest of the celebrities singing the song "America the Beautiful".[157] In 2010, during an interview with Larry King, Nelson expressed his doubts with regards to the attacks and the official story. Nelson explained that he could not believe that the buildings could collapse due to the planes, attributing instead the result to an implosion.[158]

Nelson supported Dennis Kucinich's campaign in the 2004 Democratic presidential primaries. He raised money, appeared at events, and composed the song "Whatever Happened to Peace on Earth?", criticizing the war in Iraq.[159] He recorded a radio advertisement asking for support to put musician/author Kinky Friedman on the ballot as an independent candidate for the 2006 Texas gubernatorial election.[160] Friedman promised Nelson a job in Austin as the head of a new Texas Energy Commission due to his support of bio-fuels.[161] In January 2008, Nelson filed a suit against the Texas Democratic Party, alleging that the party violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution by refusing to allow co-plaintiff Kucinich to appear on the primary ballot because he had scratched out part of the loyalty oath on his application.[162]

Nelson is an advocate for better treatment for horses and has been campaigning for the passage of the American Horse Slaughter Prevention Act (H.R. 503/S. 311) alongside the Animal Welfare Institute.[163] He is on its board of directors and has adopted a number of horses from Habitat for Horses.[164] In 2008, Nelson signed on to warn consumers about the cruel and illegal living conditions for calves raised to produce milk for dairy products. He wrote letters to Land O'Lakes and Challenge Dairy, two of the major corporations that use milk from calves raised at California's Mendes Calf Ranch, which employs an intensive confinement practice that was the subject of a lawsuit and campaign brought by the Animal Legal Defense Fund.[126] Nelson is seen in the film The Garden supporting the impoverished community South Central Farm in Southern Los Angeles.[165]

A supporter of the LGBT movement, Nelson published in 2006 through iTunes a version of Ned Sublette's "Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other", that met instant success.[166] During an interview with Texas Monthly in 2013, regarding the Defense of Marriage Act and same-sex marriage in the United States, Nelson responded to a comparison the interviewer made with the civil rights movement, stating: "We'll look back and say it was crazy that we ever even argued about this". He also presented two logos with the pink equal sign, symbol of the LGBT movement. The first one, featured the sign represented with two long braids; while the second one, featured the sign represented with two marijuana cigarettes. The use of the logos became popular quickly in social networking sites such as Twitter and Facebook.[167]

In June 2018, Nelson deplored the Trump administration family separation policy.[168] During his Fourth of July Picnic, he performed a song with Beto O'Rourke, the Democratic candidate for the Senate election in Texas. Nelson endorsed O'Rourke, and received negative reactions from the conservative part of his followers.[169] On September 29, 2018, Nelson offered a free concert in Austin supporting the candidate's run. The last number he performed was "Vote 'Em Out", a new track that was subsequently released as a single.[168]

Personal life

Nelson has been married four times and has eight children.[170] His first marriage was to Martha Matthews from 1952 to 1962. The couple had three children: Lana, Susie, and Willie "Billy" Hugh Jr. The latter died by suicide in 1991.[171] The marriage was marked by violence, with Matthews assaulting Nelson several times,[172] including one incident when she sewed him up in bedsheets and beat him with a broomstick.[173] Nelson's next marriage was to Shirley Collie in 1963. The couple divorced in 1971, after Collie found a bill from the maternity ward of a Houston hospital charged to Nelson and Connie Koepke for the birth of Paula Carlene Nelson.[172] Nelson married Koepke the same year, and they had another daughter, Amy Lee Nelson. Following a divorce in 1988, he married his current wife, Annie D'Angelo, in 1991. They have two sons, Lukas Autry and Jacob Micah.[174] In 2012, Nelson learned that he fathered a daughter with his friend Mary Haney. Born on January 22, 1953, Rene Butts (born Lynda Renee Barley) met Nelson and she shared a picture of both of them on Father's Day in 2016. Butts died in 2017.[175]

Nelson owns "Luck, Texas", a ranch in Spicewood,[176][177] and also lives in Maui, Hawaii[178] with several celebrity neighbors.[179] While swimming in Hawaii in 1981, Nelson's lung collapsed. He was taken to the Maui Memorial Hospital and his scheduled concerts were canceled.[180] Nelson temporarily stopped smoking cigarettes each time his lungs became congested, and resumed when the congestion ended.[181] He was then smoking between two and three packs per day. After suffering from pneumonia several times, he decided to quit either marijuana or tobacco. He chose to quit tobacco.[182] In 2008, he started to smoke marijuana with a carbon-free system to avoid the effects of smoke.[183] In 2004, Nelson underwent surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome, as he had damaged his wrists by continuously playing the guitar.[184] On the recommendation of his doctor, he canceled his scheduled concerts and only wrote songs during his recovery.[185] In 2012, he canceled a fund-raising appearance in the Denver area. He suffered from breathing problems due to high altitude and emphysema and was taken to a local hospital. His publicist Elaine Schock confirmed soon after that Nelson's health was good and that he was heading to his next scheduled concert in Dallas, Texas.[186] After repeated instances of pneumonia and emphysema through the years, Nelson underwent stem-cell therapy in 2015 to improve the state of his lungs.[187]

During his childhood, Nelson grew interested in martial arts. He ordered self-defense manuals on jujitsu and judo that he saw advertised in Batman and Superman comic books. Nelson started to formally practice kung fu after he moved to Nashville, in the 1960s.[188] During the 1980s, Nelson began training in taekwondo and now holds a second-degree black belt in that discipline.[189] During the 1990s, Nelson started to practice the Korean martial art GongKwon Yusul.[190] In 2014, after 20 years in the discipline, his Grand Master Sam Um presented him with a fifth-degree black belt in a ceremony held in Austin, Texas.[191] A 2014 Tae Kwon Do Times magazine interview revealed that Nelson had developed an unorthodox manner of training during the lengthy periods of time he was on tour. Nelson would conduct his martial arts training on his tour bus "The Honeysuckle Rose" and send videos to his supervising Master for review and critique.[192]

In March 2021, "I'll Be Seeing You", a new original by Nelson, was used on a public service announcement by the Ad Council to encourage COVID-19 vaccination in the United States.[193] Earlier in January 2021, Nelson and his sister received the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.[194] In May 2022, Nelson postponed several shows after he contracted COVID-19. Nelson's wife detailed that he was severely affected by the illness, and that he received a treatment including Paxlovid, monoclonal antibodies, and steroids. Nelson resumed his tour in September 2022.[195] During June 2024, Nelson had to cancel his performances at Outlaw Music Festival due to health complications and was ordered to rest for four days by a doctor.[196]

Legal issues

Nelson has been arrested several times for marijuana possession. The first occasion was in 1974 in Dallas, Texas.[197] In 1977, after a tour with Hank Cochran, Nelson traveled to The Bahamas. Nelson and Cochran arrived late to the airport and boarded the flight without luggage.[198] The bags were later sent to them. As Nelson and Cochran claimed their luggage in the Bahamas, a customs officer questioned Nelson after marijuana was found in a pair of his jeans. Nelson was arrested and jailed. As Cochran made arrangements to pay the bail, he took Nelson a six-pack of beer to his cell.[199] Nelson was released a few hours later. Inebriated, he fell after he jumped celebrating and was taken to the emergency room. He then appeared before the judge, who dropped the charges but ordered Nelson to never return to the country.[200]

In 1994, Texas Highway patrolmen found marijuana in his car near Waco, Texas. His requirement to appear in court prevented his attending the Grammy awards that year.[183] While traveling to Ann W. Richards' funeral in 2006, Nelson, along with his manager and his sister, Bobbie, were arrested in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana, and charged with possession of marijuana and hallucinogenic mushrooms.[201] Nelson received six months probation.[202]

On November 26, 2010, Nelson was arrested in Sierra Blanca, Texas, for possession of six ounces of marijuana found in his tour bus while traveling from Los Angeles back to Texas. He was released after paying bail of $2,500.[203] Prosecutor Kit Bramblett supported not sentencing Nelson to jail due to the small amount of marijuana involved, but suggested instead a $100 fine and told Nelson that he would have him sing "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain" for the court. Judge Becky Dean-Walker said that Nelson would have to pay the fine but not to perform the song, explaining that the prosecutor was joking.[204] Nelson's lawyer Joe Turner reached an agreement with the prosecutor. Nelson was set to pay a $500 fine to avoid a two-year jail sentence with a 30-day review period, which in case of another incident would end the agreement.[205] The judge later rejected the agreement, claiming that Nelson was receiving preferential treatment for his celebrity status; the offense normally carried a one-year jail sentence.[206] Bramblett declared that the case would remain open until it was either dismissed or the judge changed her opinion.[207]

Issues with the Internal Revenue Service

In 1990, the IRS seized most of Nelson's assets, claiming that he owed $32 million. In addition to the unpaid taxes, Nelson's situation was worsened by the weak investments he had made during the early 1980s.[208] In 1978, after he fired his manager Neil Reshen, Nelson was introduced by Dallas lawyer Terry Bray to the accounting firm Price Waterhouse. To repay the debt Reshen had created with the IRS, Nelson was recommended to invest in tax shelters that ultimately flopped.[209] While the IRS disallowed his deductions for 1980, 1981 and 1982 (at a time that Nelson's income multiplied),[209] due to penalties and interests, the debt increased by the end of the decade.[210]

His lawyer, Jay Goldberg, negotiated the sum to be lowered to $16 million. Later, Nelson's attorney renegotiated a settlement with the IRS in which he paid $6 million, although Nelson did not comply with the agreement.[208] Nelson released The IRS Tapes: Who'll Buy My Memories? as a double album, with all profits destined for the IRS. Many of his assets were auctioned and purchased by friends, who donated or rented his possessions to him for a nominal fee. He sued Price Waterhouse, contending that they put his money in illegal tax shelters.[211] The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount and Nelson cleared his debts by 1993.[212]

Legacy

Nelson is widely recognized as an American icon.[213][160] He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1993,[214] and he received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1998.[215] In 2011, Nelson was inducted to the National Agricultural Hall of Fame, for his labor in Farm Aid and other fund raisers to benefit farmers.[216] In 2015 Nelson won the Gershwin Prize, the lifetime award of the Library of Congress.[217] In 2018, The Texas Institute of Letters inducted him among its members for his songwriting.[218] He was included by Rolling Stone on its 100 Greatest Singers and 100 Greatest Guitarists lists.[219][220]

In 2003, Texas Governor Perry signed bill No. 2582, introduced by State Representative Elizabeth Ames Jones and Senator Jeff Wentworth, which funded the Texas Music Project, the state's official music charity. Nelson was named honorary chairman of the advisory board of the project.[221] In 2005, Democratic Texas Senator Gonzalo Barrientos introduced a bill to name 49 miles (79 km) of the Travis County section of State Highway 130 after Nelson, and at one point 23 of the 31 state senators were co-sponsors of the bill.[222] The legislation was dropped after two Republican senators, Florence Shapiro and Wentworth, objected, citing Nelson's lack of connection to the highway, his fund raisers for Democrats, his drinking, and his marijuana advocacy.[223]

An important collection of Willie Nelson materials (1975–1994) became part of the Wittliff collections of Southwestern Writers, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas. The collection contains lyrics, screenplays, letters, concert programs, tour itineraries, posters, articles, clippings, personal effects, promotional items, souvenirs, and documents. It documents Nelson's IRS troubles and how Farm Aid contributions were used. Most of the material was collected by Nelson's friend Bill Wittliff, who wrote or co-wrote Honeysuckle Rose, Barbarosa and Red Headed Stranger.[224] In 2014, Nelson donated his personal collection to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. The items include photographs, correspondence, song manuscripts, posters, certificate records, awards, signed books, screenplays, personal items and gifts and tributes from Nelson's fans.[225]

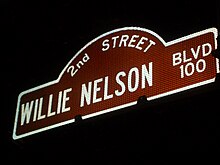

In April 2010, Nelson received the "Feed the Peace" award from The Nobelity Project for his extensive work with Farm Aid and overall contributions to world peace. On June 23, 2010, he was inducted into the Library of Congress's National Recording Registry.[226] Nelson is an honorary trustee of the Dayton International Peace Museum.[227] In 2010, Austin, Texas renamed Second Street to Willie Nelson Boulevard. The city also unveiled a life-size statue to honor him, placed at the entrance of Austin City Limits' new studio.[228] The non-profit organization Capital Area Statues commissioned sculptor Clete Shields to execute the project.[229] The statue was unveiled on April 20, 2012.[230] The date selected by the city of Austin unintentionally coincided with the number 4/20, associated with cannabis culture. In spite of the coincidence and Nelson's advocacy for the legalization of marijuana, the ceremony was scheduled also for 4:20 pm. During the ceremony, Nelson performed the song "Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die".[231] The same year, Nelson was honored during the 46th Annual Country Music Association Awards as the first recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award, which was also named after him.[232] In 2013, he received an honorary doctorate from the Berklee College of Music.[233] The following year, he was part of the inaugural class inducted into the Austin City Limits Hall of Fame. Also included among the first inductees was his friend Darrell Royal, whose jamming parties that Nelson participated in were the source of inspiration for the show.[234]

For many years, Nelson's image was marked by his red hair, often divided into two long braids partially concealed under a bandanna. In the April 2007 issue of Stuff Magazine Nelson was interviewed about his long locks.[235] "I started braiding my hair when it started getting too long, and that was, I don't know, probably in the 70's." On May 26, 2010, the Associated Press reported that Nelson had cut his hair,[236] and Nashville music journalist Jimmy Carter published a photograph of the pigtail-free Nelson on his website. Nelson wanted a more maintainable hairstyle, as well helping him stay cool more easily at his Maui home.[237] In October 2014, the braids of Nelson were sold for $37,000 at an auction of the Waylon Jennings estate. In 1983, Nelson cut his braids and gave them to Jennings as a gift during a party celebrating Jennings' sobriety.[238]

Nelson's touring and recording group, the Family, is full of longstanding members. The original lineup included his sister Bobbie Nelson, drummer Paul English, harmonicist Mickey Raphael, bassist Bee Spears, drummer/percussionist Billy English (Paul's younger brother), and guitarist Jody Payne.[239] The current lineup only includes Nelson himself, Raphael, and Billy English from the classic lineup, as Jody Payne retired (before dying in 2013), Bee Spears died in 2011, Paul English died in 2020, and Willie's sister Bobbie Nelson died in 2022.[240] Willie & Family tours North America in the bio-diesel bus Honeysuckle Rose, which is fueled by Bio-Willie.[241] Nelson's tour buses were customized by Florida Coach since 1979. The company built the Honeysuckle Rose I in 1983, which was replaced after a collision in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1990. The interior was salvaged and reused for the second version of the bus the same year. Nelson changed his tour bus in 1996, 2005 and 2013, currently touring on the Honeysuckle Rose V.[242]

Discography

- Solo studio albums

- ...And Then I Wrote (1962)

- Here's Willie Nelson (1963)

- Country Willie: His Own Songs (1965)

- Country Favorites: Willie Nelson Style (1966)

- Make Way for Willie Nelson (1967)

- The Party's Over (1967)

- Texas in My Soul (1968)

- Good Times (1968)

- My Own Peculiar Way (1969)

- Both Sides Now (1970)

- Laying My Burdens Down (1970)

- Willie Nelson & Family (1971)

- Yesterday's Wine (1971)

- The Words Don't Fit the Picture (1972)

- The Willie Way (1972)

- Shotgun Willie (1973)

- Country Winners (1973)

- Phases and Stages (1974)

- Red Headed Stranger (1975)

- The Sound in Your Mind (1976)

- The Troublemaker (1976)

- To Lefty from Willie (1977)

- Stardust (1978)

- Willie Nelson Sings Kristofferson (1979)

- Pretty Paper (1979)

- Family Bible (1980)

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow (1981)

- Always on My Mind (1982)

- Tougher Than Leather (1983)

- Without a Song (1983)

- City of New Orleans (1984)

- Angel Eyes (1984)

- Me & Paul (1985)

- Partners (1986)

- The Promiseland (1986)

- Island in the Sea (1987)

- What a Wonderful World (1988)

- A Horse Called Music (1989)

- Born for Trouble (1990)

- The IRS Tapes: Who'll Buy My Memories? (1992)

- Across the Borderline (1993)

- Moonlight Becomes You (1994)

- Healing Hands of Time (1994)

- Just One Love (1994)

- Spirit (1996)

- Teatro (1998)

- Night and Day (1999)

- Me and the Drummer (2000)

- Milk Cow Blues (2000)

- Rainbow Connection (2001)

- The Great Divide (2002)

- Nacogdoches (2004)

- It Always Will Be (2004)

- Countryman (2005)

- You Don't Know Me: The Songs of Cindy Walker (2006)

- Songbird (2006)

- Moment of Forever (2008)

- American Classic (2009)

- Country Music (2010)

- Remember Me, Vol. 1 (2011)

- Heroes (2012)

- Let's Face the Music and Dance (2013)

- To All the Girls... (2013)

- Band of Brothers (2014)

- Summertime: Willie Nelson Sings Gershwin (2016)

- For the Good Times: A Tribute to Ray Price (2016)

- God's Problem Child (2017)

- Last Man Standing (2018)

- My Way (2018)

- Ride Me Back Home (2019)

- First Rose of Spring (2020)

- That's Life (2021)

- The Willie Nelson Family (2021)

- A Beautiful Time (2022)

- I Don't Know a Thing About Love (2023)

- Bluegrass (2023)

- The Border (2024)

Filmography

Bibliography

- Willie: An Autobiography, Simon & Schuster, 1988, with Bud Shrake

- The Facts of Life and Other Dirty Jokes, Random House, 2002

- Farm Aid: A Song for America, Rodale Books, foreword by Willie Nelson, 2005

- The Tao of Willie: A Guide to the Happiness in Your Heart, Gotham, 2006, with Turk Pipkin

- On the Clean Road Again: Biodiesel and the Future of the Family Farm, Fulcrum Publishing, 2007

- A Tale Out of Luck (a novel), Center Street, 2008, with Mike Blakely

- Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die: Musings From the Road, William Morrow, foreword by Kinky Friedman, 2012

- It's a Long Story: My Life, Little, Brown and Company, 2015 with David Ritz

- Pretty Paper, Penguin Random House, 2016 with David Ritz

- Willie Nelson's Letters to America, HarperCollins, 2021 with Turk Pipkin

- Me and Sister Bobbie: True Tales of the Family Band, Penguin Random House, 2021 with Bobbie Nelson and David Ritz

- Sister, Brother, Family: An American Childhood in Music, Penguin Random House, 2021 with Bobbie Nelson and Chris Barton

- Me And Paul: Untold Stories of a Fabled Friendship, HarperCollins, 2022 with David Ritz

- Energy Follows Thought: The Stories Behind My Songs, HarperCollins, 2023 with Mickey Raphael and David Ritz

See also

- List of celebrities who own cannabis businesses

- List of Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- List of country music performers

- Music of Austin, Texas

References

- ^ a b c Patoski 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b Scobey 1982, p. 58.

- ^ Hunt 2009.

- ^ a b c Nelson 2007a, p. 29.

- ^ Laufenberg 2005, p. 473.

- ^ a b Patoski 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Reid 2004, p. 218.

- ^ Malone 2002, p. 303.

- ^ Patoski 2008.

- ^ a b Kienzle 2003, p. 236.

- ^ Richmond 2000, pp. 7, 8, 23.

- ^ Scobey 1982, p. 47.

- ^ "Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard Sing About Influences and Friendship on "Django and Jimmie" CD". July 12, 2015.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Hann 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Myers 1969, p. 4.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 392.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Thomson 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 92.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Patoski 2008, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Evans 2006, p. 70.

- ^ a b Dicair 2007, p. 246.

- ^ a b Erlewine 1997, p. 324.

- ^ Dingus 1992, p. 77.

- ^ a b Myers 1969, p. 5.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 116, 117.

- ^ Smith 2013.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 117.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 118.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Kosser 2006, p. 73.

- ^ a b NPR staff 1996.

- ^ Edwards & Callahan 2001.

- ^ Bush & Mitchell 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Scobey 1982, p. 190.

- ^ Reid 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. Nashville, 1960.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 158.

- ^ Bush & Mitchell 2007, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Kienzle 2003, p. 248.

- ^ a b Reid 2004, p. 223.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 167.

- ^ Reid & Sahm 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Thomas 2012.

- ^ Reid 2004, p. [1].

- ^ Milner 1998, p. 183, 184.

- ^ Harden et al. 1996, p. 169.

- ^ Tichi 1998, p. 341.

- ^ Erlewine 2007.

- ^ Dicair 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Dicair 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Wolff & Duane 2000, p. 367.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Hartman 2008, p. 174.

- ^ Hartman & 2008, p. 175.

- ^ RIAA staff 2010.

- ^ Erlewine 2008.

- ^ RIAA staff 2 2010.

- ^ a b Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 263.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 262.

- ^ Jennings & Kaye 1996, p. 10.

- ^ RIAA staff 3 2010.

- ^ Billboard 1976.

- ^ Tribe 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Harrison, Thomas 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Jurek 2008.

- ^ Monkman 2008.

- ^ Poe 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Erlewine 2005.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 383.

- ^ Edwards 2015.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 368.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 342.

- ^ Hochman 1996.

- ^ Liner notes, Twisted Willie. Justice Records. 1996.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 430.

- ^ Farm Aid Staff 2011.

- ^ Erlewine 2000.

- ^ BMI staff 2003.

- ^ Biography staff 2011.

- ^ Pareles 2003.

- ^ Entertainment One staff 2003.

- ^ Toots and the Maytals 2016.

- ^ Deusner 2005.

- ^ BBC News staff 2005.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 360.

- ^ a b Cooper 2014.

- ^ Willie Nelson.com staff 2011.

- ^ Evans-Price 2010.

- ^ Erlewine 2010.

- ^ CBS Music staff 2011.

- ^ Sugimoto 2011.

- ^ Willie Nelson.com staff 2012.

- ^ Billboard staff 2012.

- ^ Vinson 2013.

- ^ Jessen 2013.

- ^ Leahey 2014.

- ^ Holden 2014.

- ^ Asker 2017.

- ^ Daly 2018.

- ^ Shanley 2019.

- ^ Lanois 2019.

- ^ Brickey 2018.

- ^ Asker 2019.

- ^ Kroll 2020.

- ^ Margolis 2020.

- ^ France 2020.

- ^ Rosenthal 2020.

- ^ Willman 2020.

- ^ Kreps 2020.

- ^ "Hear Karen O and Willie Nelson's Transformative Cover of Queen and David Bowie's 'Under Pressure'". Rolling Stone. October 28, 2020. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Cummings, Tommy 2022.

- ^ Farias, Robbie 2023.

- ^ "Willie Nelson's 90th Birthday Concert: Weed, Well Wishes and Tons of Songs". Rolling Stone. April 30, 2023.

- ^ RockHall 2023.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (March 28, 2024). "Beyoncé's 'Cowboy Carter' Features a Beatles Cover, Miley Cyrus, and Post Malone". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Allmovie staff 2011.

- ^ Yahoo! Movies staff 2011.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000.

- ^ George-Warren & Hoekstra 2005.

- ^ NPR staff 2010.

- ^ a b Nelson 2008.

- ^ Whitaker 2012.

- ^ Hachette staff 2015.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2016.

- ^ Carey 2003.

- ^ SmithTaylor 2008, p. 173.

- ^ Associated Press staff 2005.

- ^ a b Brick, Michael 2014.

- ^ Dunn 2011.

- ^ Willie's Place staff 2010.

- ^ Chagollan 2010.

- ^ Opry.com staff 2011.

- ^ Swiatecki 2014.

- ^ Guardian Music staff 2015.

- ^ Lodderhose 2016.

- ^ Solomon 2017.

- ^ a b Hautzinger 2017.

- ^ Locke 2017.

- ^ Appleford 2017.

- ^ a b c Erlewine 2015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica staff 2011.

- ^ a b Nelson 2005.

- ^ a b c Willie Nelson General Store staff 2010.

- ^ Reinert 1976, p. 103.

- ^ a b Draper 1991, p. 103.

- ^ Durchholz & Graff 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Durchholz & Graff 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Richmond 2000, p. 94.

- ^ NORML staff 2009.

- ^ High Times staff 2007.

- ^ Thomson 2010.

- ^ Quay & Damico 2010, p. 149.

- ^ O'Reilly 2010.

- ^ Reuters staff 2004.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2010.

- ^ Burt 2005.

- ^ Selby 2009.

- ^ Nelson 2007b.

- ^ Habitat for Horses staff 2011.

- ^ Kennedy 2019.

- ^ Neu 2006.

- ^ Langer 2013.

- ^ a b Hudak 2018.

- ^ Taylor 2018.

- ^ Hollabaugh 2010.

- ^ Hall 2008.

- ^ a b Cartwright 2000, p. 276.

- ^ Goldman 2012.

- ^ Riggs 2007, p. 239.

- ^ Krauser, Emily 2023.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff 2017.

- ^ Parker 2014.

- ^ Kane 2008.

- ^ Grigoriadis 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Krebs 1981.

- ^ O'Hare 2010.

- ^ NPR staff 2012.

- ^ a b Patoski 2011.

- ^ Associated Press staff 2002.

- ^ Miller Loncaric 2008.

- ^ McKinnley 2012.

- ^ Heim 2015.

- ^ Nelson, Shrake & Shrake 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Chilton 2012.

- ^ Hall 2014.

- ^ Chilton 2014.

- ^ Zirogiannis 2014.

- ^ Weisholtz, Drew 2021.

- ^ Doyle, Patrick 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Tiffany 2022.

- ^ Morrow, Brendan. "Willie Nelson cancels Outlaw Music Festival performances for health reasons". USA Today. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Goddard 2010.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 247.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 248.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 249.

- ^ People staff 2006.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 471.

- ^ Cline 2010.

- ^ Caulfield 2011.

- ^ Amter 2011.

- ^ TMZ staff 2011.

- ^ Cohen 2012.

- ^ a b Draper 1991, p. 177.

- ^ a b Patoski 2008, p. 407.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 406.

- ^ Cowan 1991.

- ^ Johnston 1995.

- ^ PBS staff 2011.

- ^ Edwards 1993.

- ^ Kennedy Center staff 2011.

- ^ Treolo 2011.

- ^ Leahey 2015.

- ^ Merschel 2018.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff 2010.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff 2011.

- ^ Texas Music Project staff 2011.

- ^ Ward 2005.

- ^ Fort Worth Star-telegram staff 2005.

- ^ Alkek Library staff 2010.

- ^ Briscoe Center staff 2014.

- ^ Donahue 2010.

- ^ Dayton Peace Museum staff 2010.

- ^ BBC News staff 2010.

- ^ Houston Chronicle staff 2010.

- ^ Tomlinson 2012a.

- ^ Tomlinson 2012b.

- ^ Lewis 2012.

- ^ Sullivan 2013.

- ^ Associated Press staff 2014.

- ^ Everett 2010.

- ^ Associated Press staff 2010.

- ^ Carter 2010.

- ^ New York Post staff 2014.

- ^ Scobey 1982, pp. 198, 358.

- ^ Kerns 2012.

- ^ Vancouver Province staff 2007.

- ^ Langer 2014.

Sources

- Alkek Library staff (September 22, 2010). "Largest Willie Nelson collection now at Texas State". Alkek Library News. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- "The Electric Horseman". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- Allmovie staff (2011). "Willie Nelson". AllMovie. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Amter, Charlie (June 7, 2011). "Willie Nelson Dodges Jail in Texas". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Appleford, Steve (May 15, 2017). "'American Epic': Inside Jack White and Friends' New Roots-Music Doc". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Asker, Jim (May 9, 2017). "No 'Problem': Willie Nelson's New Album Bows at No. 1". Billboard. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- Asker, Jim (June 2, 2019). "Lee Brice's 'Rumor' Tops the Country Airplay Chart, Willie Nelson Takes a New 'Ride'". Billboard. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Associated Press staff (May 13, 2002). "Willie Nelson cancels concerts". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- Associated Press staff (January 14, 2005). "Willie Nelson Bets on Biodiesel Publications". Wired Magazine. Associated Press. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Associated Press staff (May 26, 2010). "The pigtails are gone: Willie Nelson cuts his hair". Las Cruces Sun-News. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Associated Press staff (April 27, 2014). "Matthew McConaughey and others celebrate Willie Nelson". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- BBC News staff (January 10, 2005). "Willie Nelson stages tsunami gig". BBC News. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- BBC News staff (May 28, 2010). "Willie Nelson to have street named after him in Texas". BBC News. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Billboard (December 25, 1976). "Singles". Billboard. Vol. 88, no. 52. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- Billboard staff (2012). "Chart listing for Heroes". Billboard. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- Biography staff (2011). "Toby Keith Biography". Biography. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- BMI staff (July 15, 2003). "BMI Cheers 'Beer for My Horses' with Willie, Toby and Scotty". BMI. Broadcast Music. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Brick, Michael (October 30, 2014). "For Willie Nelson, a biodiesel dream deferred". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- Brickey, Kelly (March 15, 2018). "Willie Nelson, Miranda Lambert to Honor Elton John on Biggest Hits Cover Albums". Soundslikenashville.com. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Bush, Johnny; Mitchell, Rick (2007). Whiskey River (Take My Mind): The True Story of Texas Honky-Tonk. University of Texas Tech. ISBN 978-0-292-71490-8.

- Briscoe Center staff (May 8, 2014). "Briscoe Center Acquires Willie Nelson Collection". Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on May 19, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- Burt, Jim (August 22, 2005). "Kinky Friedman To Name Willie Nelson as Texas Energy Czar". The Car Connection. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Carter, Jimmy (May 26, 2010). "Willie cuts his hair".

- Cartwright, Gary (2000). Turn Out the Lights: Chronicles of Texas in the 80's and 90's. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71226-3.

- Carey, Brian (September 28, 2003). "Legendary Food, Legendary Service, and Legendary People". Epinions. Shopping.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Caulfield, Phillip (March 30, 2011). "Judge says request for Willie Nelson to sing 'Blue Eyes' in court was a joke". Daily News. New York. News Wire Services. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- CBS Music staff (February 3, 2011). "Last.fm Trends: Willie Nelson's On Grammy Road Again". Last.fm. CBS. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- Chagollan, Steve (March 15, 2010). "Willie Nelson launches Luck Films: Musician-actor in joint venture that aims to make up to five pics a year". Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Chilton, Martin (December 14, 2012). "Willie Nelson interview: Don't fret about the end of the world". The Telegraph Limited. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- Chilton, Martin (April 29, 2014). "Willie Nelson gets 5th-degree black belt at 81". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- Chapman, Roger (2010). Culture wars: an encyclopedia of issues, viewpoints, and voices, Volume 1. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1761-3. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- Cline, Georgette (November 27, 2010). "Willie Nelson Arrested for Marijuana Possession". The Boot. AOL. Associated Press. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- Cohen, Jason (February 3, 2012). "Win the Weekend: Was Willie's Case Ever Settled?". Texas Monthly. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Cooper, Peter (June 26, 2014). "Buddy Cannon witnesses Willie Nelson's magic". The Tennessean. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- Cowan, Alison Leigh (September 2, 1991). "Willie Nelson Hopes for a Hit; So Does the I.R.S". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Cummings, Tommy (December 20, 2022). "'Willie Nelson and Family' documentary to premiere at Sundance Film Festival". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- Daly, Rhian (November 4, 2018). "Listen to Josh Homme's new track 'Cruel, Cruel World', taken from 'Red Dead Redemption 2' soundtrack". NME.

- Dayton Peace Museum staff (2010). "Dayton International Peace Museum". Dayton International Peace Museum. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- Deusner, Stephen M (July 25, 2005). "Willie Nelson: Countryman". Pitchfork. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Dicair, David (2007). The First Generation of Country Music Stars. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3021-5.

- Dingus, Anne (1992). "Ernest Tubb Goes Electric and 51 More Moments to Remember Texas' Rich Musical Past". Texas Monthly. Vol. 19, no. 2. ISSN 0148-7736.

- Donahue, Ann (June 23, 2010). "Tupac, Willie Nelson, R.E.M. Among Inductees To National Recording Register". Billboard. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Doyle, Patrick (January 14, 2021). "It's All Going to Shot: Willie Nelson Gets the Covid Vaccine". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- Draper, Robert (May 1991). "Texas Monthly". Domain: The Lifestyle Magazine of Texas Monthly. Vol. 19, no. 5. p. 100. ISSN 0148-7736. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- Dunn, Jill (January 27, 2011). "A Creditor forecloses Willie's Place". Overdrive Magazine. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Durchholz, Daniel; Graff, Gary (2010). Neil Young: Long May You Run. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3647-2. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Edwards, David; Callahan, Mike (2001). "The Liberty Records Story". Both Sides Now. Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- Edwards, Gavin (2015). "'We Are the World': A Minute-by-Minute Breakdown on Its 30th Anniversary". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- Edwards, Joe (September 30, 1993). "Willie Nelson inducted in Hall of Fame". Bangor Daily News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- Everett, Christina (May 27, 2010). "Willie Nelson haircut: Country singer chops off trademark long tresses and debuts shorter new look". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Encyclopædia Britannica staff (2011). "Willie Nelson (American musician)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Entertainment One staff (2003). Ringo Rama (Booklet). Ringo Starr. Koch, Entertainment One. 038 411-0, 038 412–2, 038 413–9.

- Erlewine, Michael (1997). All Music Guide to Country: The Experts' Guide to the Best Recordings in Country Music. Miller Freeman. ISBN 978-0-87930-475-1.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2000). "VH1 Storytellers". AllMusic. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2005). "WWII". Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2007). "Shotgun Willie/Phases and Stages". Rovi Corporation. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2008). "The Troublemaker – Willie Nelson". Rovi Corporation. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2010). "Country Music: Billboard albums". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2015). "Willie Nelson – Biography". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Evans, Mike (2006). Country Music Facts, Figures & Fun. AAPPL. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-904332-53-4. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- Evans-Price, Deborah (April 21, 2010). "Willie Nelson Delivers True 'Country Music'". The Boot. AOL. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- Farias, Robbie (February 6, 2023). "Willie Nelson wins Grammy for best country album and best country solo performance". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- Farm Aid Staff (2011). "Past concerts – Farm Aid". Farm Aid. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Fort Worth Star-telegram staff (April 28, 2005). "'Nelson Highway' isn't a hit with GOP". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- France, Lisa Respers (April 17, 2020). "Willie Nelson hosting 'Come and Toke It' variety show on 4/20". CNN.

- George-Warren, Holly; Hoekstra, Dave (October 7, 2005). Farm Aid: A Song for America. Rodale Books. ISBN 978-1-59486-285-4.

- Goddard, Steve (November 30, 2010). "Willie Nelson's Mug Shot From Last Friday Night". 94.5 KOOL FM. CBS Radio. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- Goldman, Andrew (December 14, 2012). "Willie Nelson, the Silver-Headed Stranger" (Interview). The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- Goldstein, Tiffany (August 29, 2022). "Willie Nelson's Wife Annie Opens Up About Her Husband's Nerve-Wracking Battle With COVID-19". CMT News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- Hann, Michael (May 17, 2012). "Willie Nelson: 'If We Made Marijuana Legal, We'd Save a Whole Lotta Money and Lives'". The Guardian. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- Hudak, Joseph (October 11, 2018). "Hear Willie Nelson's Studio Version of New Song 'Vote 'Em Out'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Grigoriadis, Vannessa (January 14, 2007). "Move to a Fantasy Island". New York Magazine. Vol. 40, no. 1–7.

- Guardian Music staff (March 27, 2015). "Willie Nelson to open chain of marijuana stores". Guardian Music. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- Habitat for Horses staff (2011). "Habitat for Horses signature series". Habitat for Horses. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Hachette staff (2015). It's a Long Story: My Life by Willie Nelson. Hachette Book Group; Little, Brown and Company. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.