Texas Centennial half dollar

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 U.S. dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm (1.20 in) |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition | |

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1934–1938 |

| Mint marks | D, S. To the right of Victory's foot on the reverse. Philadelphia Mint coins struck without mint marks. |

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | An eagle perched atop an oak branch in front of the Lone Star of Texas. |

| Designer | Pompeo Coppini |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | The goddess Victory spreading her wings over the Alamo. Portraits of Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin embedded within clouds to the sides. The Six Flags of Texas fly above her head, alongside the banner "Liberty". |

| Designer | Pompeo Coppini |

The Texas Centennial half dollar was a commemorative fifty-cent piece struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint for collectors from 1934 to 1938. It features an eagle and the Lone Star of Texas on the obverse, while the reverse is a complex scene incorporating the winged goddess Victory, the Alamo Mission, portraits of Texan founding fathers Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin, alongside the six flags over Texas. Proposed by the American Legion's Texas Centennial Committee as a fundraising measure for the 100th anniversary of Texas independence from Mexico, the coin's issue was approved by Congress in 1933, ending a multi-year pause on new commemorative issues under the Hoover administration. It was designed by sculptor Pompeo Coppini, previously the designer of several Texan public monuments. Rough models of the coin were approved by the committee in May 1934, but rejected by the United States Commission of Fine Arts, who viewed the design as crowded and overly-complicated. A compromise was reached, and the entered production at the Philadelphia Mint in October 1934.

The Centennial Committee intended the coins to help finance the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin, and vended them through the American Legion and banks across Texas. The vast majority of this initial, 1934-dated, issue went unsold and was sent back to the Mint to be melted down for its silver. Smaller issues were produced at the Philadelphia, Denver, and San Francisco mints for the next four years, even beyond the centennial itself in 1936. The Texas Centennial Committee ceased sales of the coin in November 1938. Despite their relative lack of sales, the issue has proven popular with collectors, and have gradually appreciated in value.

Authorization

In the early 1930s, the American Legion's organization in Texas voted to participate in the Centennial of Texas Independence in 1936, and considered how best to contribute to the celebrations, including the Texas Centennial Exposition, a world's fair set to take place in Dallas in 1936. A. Garland Adair led the Centennial Committee, which decided upon a commemorative coinage issue, likely inspired by the Oregon Trail Memorial half dollar, with the profits to be used to finance a museum. Texas congressman William D. McFarlane, enjoying friendly connections to the committee, had pushed for the creation of a coin to commemorate the centennial.[1][2] Such a method of funding had been proposed by state representative Temple Harris McGregor in March 1932, who proposed the issue of 50,000 half dollars for sale to patriotic citizens at $1 each.[3]

The American Legion decided that funds generated by the coins would be used to construct a museum building on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin as its contribution toward the Texas Centennial.[4] Opposition to commemorative coinage due to counterfeiting concerns led to various failed commemorative coinage bills during the administration of Herbert Hoover, including the vetoed Gadsden Purchase half dollar. A more favorable climate was found under Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration.[5][6]

Legislation for a commemorative half dollar "in commemoration of the one hundredth anniversary in 1936 of the independence of Texas and of the noble and heroic sacrifices of her pioneers, whose memory has been an inspiration to her sons and daughters during the past century" passed the United States Senate on June 7, 1933, without recorded debate or dissent.[7] The bill had been introduced by Senator Tom Connally of Texas; it was sponsored in the House by Wright Patman, also of that state.[8] It was brought to the floor of the House of Representatives on June 10, 1933, by Martin Dies Jr. of Texas, having already passed the House Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. Bertrand H. Snell of New York asked how the coinage dies would be paid for, and James McClintic of Oklahoma inquired if Dies would seek an appropriation, but Dies assured the House that the American Legion of Texas would pay all expenses.[9] The bill became law on June 16, 1933 with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who gave the pen he used to sign the law to Senator Connally, who had urged the passage of the legislation.[10] The pen was intended to be the first exhibit of the new museum.[2]

The bill provided for up to 1,500,000 coins to be issued, which could be purchased by the American Legion Texas Centennial Committee at face value,[11] for resale to collectors. Even though the centennial was not to be celebrated until 1936, the committee planned to issue coins before that, so as to be able to finance the museum's contribution. Under the law, the coins could be struck in multiple years and at multiple mints, creating different varieties that collectors wanting a complete set would have to purchase.[5][12]

Preparation

The Texas Centennial Commission hired Pompeo Coppini, a prominent Italian-American sculptor, to design the coin. While based in Texas, his main studio was located in New York City. Coppini had previously designed various public monuments in Texas, prominently including the Littlefield Fountain of the University of Texas at Austin.[13][14] According to Adair, Coppini did not charge for his services.[15]

By May 1934, Coppini completed models of both faces of the coin, later described as "unusually crude" by numismatist Don Taxay. These included a large number of design elements, likely requested by the Centennial Committee itself. Following the approval of the committee, the designs were sent to the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) for examination.[1][5] Charles Moore, the chair of the commission, had become critical of the commemorative half-dollar series, and took an especially dim view of Coppini's initial models, describing them as a conglomeration of "the whole history of Texas and all its leading personages in a perfect hodgepodge."[5] Sculptor and CFA member Lee Lawrie also criticized the design, and wrote an extensive request for design alterations to the model. Lawrie recommended the removal of the six flags over Texas and the winged goddess Victory, to be replaced by a design focused on the Alamo, alongside Texan founding fathers Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin.[5]

The commission approved Lawrie's recommendations and sent them to Coppini and McFarlane. While Coppini wrote in response that the models were intended as rough sketches, McFarlane was insistent on the use of the modeled designs. CFA members eventually dropped their broader criticisms of the design, accepting adjustments to the specific design elements of the coin. Lawrie met with Coppini in early June and the two agreed on a number of changes. The revised designs were approved by the commission on June 25, 1934, with the Treasury consenting shortly thereafter.[16]

Design

The obverse includes a bald eagle perched in front of the Lone Star of Texas. The presence of an eagle on the obverse is a change from many other American coins, which traditionally feature eagles on the reverse. In early models of the coin, the eagle held a laurel wreath in its claws, but this was changed to an oak branch for the final design. Six stars accompany the label of Half Dollar at the bottom, likely referencing the six flags that have flown over Texas. Dual mottoes of In God We Trust and E pluribus unum flank the star. The text United-States-of-America, arcing along the upper edge of the obverse, is hyphenated for unknown reasons.[17]

The reverse features a complicated series of elements. The winged goddess Victory, wearing a liberty cap, crouches while holding the Alamo and an olive branch. Besides her, embedded within clouds, are two tondo busts of Texas leaders Sam Houston and Stephen Austin, each identified by an extremely small label. Behind the central figure are the six flags,[α] although these are indistinct and partially obscured by a scroll bearing the word Liberty, an addition required by the Coinage Act of 1792. The motto Remember The Alamo, a Texian rallying cry during the Revolution, is placed along the bottom edge of the reverse. When a mint mark is present, it is placed below Victory. Coppini's initials, P. C., are adjacent to the bottom-right corner of the Alamo.[17][19]

Reception

Lawrie, writing to Fine Arts Commission secretary H. P. Caemmerer shortly before the coin's approval, described the final design as "much improved" over the initial model, but ultimately held by the large number of separate design elements.[16] In 1937, Fort Worth coin dealer B. Max Mehl wrote that the depiction of Victory was unnecessary and detracted focus from the Alamo motif. He also stated that the design was of high quality at a larger scale, but "when reduced to actual coin size, it is not too hot."[20]

Art historian and numismatist Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III described the complex reverse of the coin as Coppini's tour de force and "a classic triumph of how much can be successfully crowded on a coin".[13] Numismatists Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen held a much dimmer view of the coin, describing the reverse design as "impossibly confusing", and especially prone to illegibility due to poor striking.[21]

Production and distribution

1934 issue

205,113 of the coins were produced at the Philadelphia Mint in October and November 1934. Although much lower than the initially authorized 1,500,000, this was considered a large mintage for a commemorative of this period.[6][22] Distribution was slightly delayed from an initial target of November 1934, to become available to the public the following month.[6] Most of the mintage was sent to the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank and its branches at Houston, San Antonio and El Paso, with more to be sent if needed and paid for.[23]

The first coins to be vended were sold on December 15 via auction from the steps of the Texas State Capitol in Austin, following a parade. Former governor James E. Ferguson bought the first coin for $90 for presentation to his wife, the current governor, Miriam A. "Ma" Ferguson. The second coin to reach Texas went to Austin Mayor Tom Miller for $50.[24] Some of the coins were placed on exhibit at the Austin Chamber of Commerce so the public would know what they looked like.[2]

The initial mintage was mainly distributed through Texan banks, available at a price of one dollar per coin,[6] on sale throughout the state beginning on December 20, 1934.[2] Legion officials put the first coins to be sold in a number of cities for sale at auction–in Panhandle, the first two coins brought $40 and $10; in Amarillo, they brought $35 each.[23] The extra funds gained from the preliminary auctions were intended to cover the Legion's expenses, so that fifty cents from every coin sold could go to the museum.[25]

In early March 1935, examples of the coin were presented both to President Roosevelt and to Vice President John Nance Garner.[26] Civic organizations and other groups joined the Legion in selling the coins; Amarillo had a quota of 5,000 half dollars.[27] By the end of February, residents of Paris, Texas had bought 95 of their city's quota of 100 coins.[28]

Later issues

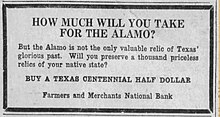

The American Legion Texas Centennial committee is asking the public to buy Texas Centennial half-dollars. They are being sold at $1 each. the entire premium of 50¢ on the dollar to go into a fund for the building of the Texas Memorial Museum on the campus of the University of Texas. ... The gift of the fund to Texas constitutes the brightest chapter in the illustrious history of the American Legion of Texas. Your half-dollar will grow in value with the passing of the years. Heroes died for Texas. Heroes will buy for Texas. Secure today your Keepsake for Texas' sake. "A coin in every Texas home".

While the press reported on April 1, 1935 that about 100,000 coins had been sold,[30] this was soon contradicted, as in June, Adair reported sales of 80,000 (with half outside Texas)[31] and on December 1, the San Angelo Standard-Times reported that all but 30,000 remained unsold. The museum project gained a $225,000 appropriation from the Texas Legislature and one of $300,000 from Congress, and responsibility for the coins transferred to the board of directors of the museum, with Beauford H. Jester, of Corsicana, Texas, designated head of the coin fundraiser.[32][33]

Due to the lack of demand, 143,650 unsold coins were melted by the Treasury, as the Mint would not strike more until the 1934 issue was paid for or destroyed.[6] In August 1935, Adair had suggested that coins with that year's date would be ordered from the Mint,[34] and in November, Assistant Director of the Mint Mary M. O'Reilly confirmed this.[35] The Philadelphia, Denver, and San Francisco mints produced 10,000 coins each in November 1935, alongside a small number of pieces reserved for assay purposes. The 1935 issue was sold at a raised price of $1.50 per coin, while the committee's remaining stock of 1934 coins were available for $1.15 each.[6] The coins were shipped to buyers in envelopes, occasionally in cardboard holders. Some were packaged unofficially by Mehl in boxes.[36] In December 1935, O'Reilly announced that 30,000 Texas Centennial half dollars would be struck dated 1936.[37] Mehl wrote soon after, "I am not entirely free from guilt that so many different issues of these coins were issued. The Committee called on me and I gave them my idea as to how to sell more of the coins."[38]

Adair attributed the poor sales of the 1934 issue to a small advertising budget. Walter P. Nichols, later a distributor of the York County Tercentenary half dollar, wrote to Adair recommending that the committee pursue a design change to sell more coins. As alterations to the design required congressional approval, Texas senator Tom Connally introduced a bill in 1936 to allow for a new edition of the coin. The bill, S. 3721, permitted five separate designs variations in an attempt to drive further sales, and it received a hearing on March 11, 1936 before a committee led by Senator Alva B. Adams of Colorado.[39][40] Adams's committee heard testimony from El Paso coin dealer Lyman W. Hoffecker and from Frank Duffield, editor of The Numismatist. They testified that there had been several issues of commemorative coins struck over multiple years and at all three mints. This raised the total cost to the collector in a way they considered abusive. The proposal for five designs did not pass.[41][42]

Meanwhile Jester attempted to sell the coins that had been already struck, announcing in February 1936 that there would be sales committees formed in each of Texas's 31 state senatorial districts. At that time, the coins were being sold by 314 banks in 236 Texas municipalities.[43] Jester, who set prices at $1.50 for 1935-dated coins and $1.15 for 1934, disclosed that 30,000 Texas half dollars had been sold, of which the majority had been sold outside of Texas.[44] On April 25, Adair announced that the 1936-dated coins were going on sale at $4.50 per set of three, that the 1935 issue had sold out, and that the 1934 issue was still available.[45]

Ground was broken for the museum by President Roosevelt on June 11, 1936.[46] The coin was sold at a booth at the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas, as well as at the celebrations at Austin on the university campus, at Frontier Days in Fort Worth,[47] at the National Tomato Festival in Jacksonville, Texas,[48] and by the University of Texas Longhorn Band on its train tour of the East and Southeast in honor of the centennial.[49]

The coins continued to be used as a fundraiser for the museum. Low sales continued, but an issue of around 8,000 coins was produced at each of the three mints in April–May 1937. [39][40] In August, with the museum nearing completion, the Victoria Advocate printed a figure for total sales as 132,111.[50] The museum was dedicated December 19, 1937, with Governor James V. Allred presiding at the ceremony,[51] and opened to the public on August 15, 1938. United Press reported that it represented "two years of sales of Texas Centennial half dollars, two years of construction, and a cost of $600,000."[52]

A final issue of 5,000 coins was struck at each mint in January 1938, sold by the committee at an increased price of $2.00 per coin.[39][40] Charles J. Harris, executive secretary of the coin committee, stated that the sale would likely raise sufficient funds to pay off remaining obligations against the museum.[53] The committee struggled to sell both the 1938 issues and their remaining stock of coins from previous years; many were returned to the Treasury for melting following the end of sales in November 1938. In total, 304,000 coins were struck during the four year period of issue, far short of the originally authorized figure of 1,500,000. Of these, a slight majority, 154,522 coins, were returned and melted down by the Treasury.[39][40] On August 5, 1939, Congress cancelled all unexpired authorizations for commemorative coins, officially putting an end to the Texas and several other commemorative coin series struck in multiple years, such as the Oregon Trail issue.[54]

Mintage figures

| Date | Mint | Distributed | Assay | Melted | Net |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | (P) | 205,000 | 113 | 143,650 | 61,350 |

| 1935 | (P) | 10,000 | 8 | 12 | 9,988 |

| D | 10,000 | 7 | 0 | 10,000 | |

| S | 10,000 | 8 | 0 | 10,000 | |

| 1936 | (P) | 10,000 | 8 | 1,097 | 8,903 |

| D | 10,000 | 7 | 968 | 9,032 | |

| S | 10,000 | 8 | 943 | 9,057 | |

| 1937 | (P) | 8,000 | 5 | 1,434 | 6,566 |

| D | 8,000 | 6 | 1,401 | 6,599 | |

| S | 8,000 | 7 | 1,370 | 6,630 | |

| 1938 | (P) | 5,000 | 5 | 1,225 | 3,775 |

| D | 5,000 | 5 | 1,230 | 3,770 | |

| S | 5,000 | 6 | 1,192 | 3,808 |

Collecting

Although the 1934 issue of the coin is by far the most numerous, it was treated as a novelty souvenir, and is thus commonly found in mishandled or circulated condition. Poor strikes are common, especially on the reverse of the coin, as are damages from whizzing or polishing. Price variations between the various issues are minor in lower mint-state grades, but diverge significantly in MS-65 and beyond. Swiatek described the 1935-D coin as the most appealingly produced in the series, with proof-like appearances early in the production run.[55]

Despite low sales, the coins found popularity among collectors. They remained at roughly their original issue price until the 1950s, after which they began appreciating. By the 1980s, mint-state examples were sold for well over $100 per coin, with higher prices for the .[56] The deluxe edition of R. S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2020, lists the coin for between $130 and $1,900, depending on date, mint mark and condition. An exceptional specimen of the 1936 issue struck at Philadelphia sold for $14,100 in 2015.[57]

Notes

- ^ Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the United States, and the Confederate States of America[18]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Swiatek & Breen 1981, pp. 234–237.

- ^ a b c d Barnes, Lorraine (December 19, 1934). "War Vet Swings $1,500,000 Deal And Wins That Sum --In Pleasure". Austin American-Statesman. p. 1. Retrieved July 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Plan Outlined for Jubilee in Texas". Abilene Daily Reporter. March 3, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Centennial Coin Bill Sent to F.D. For Signature". Austin American-Statesman. June 11, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Taxay 1967, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b c d e f Bowers 1991, p. 267.

- ^ "Congressional Record, June 7, 1933, p. 5148" (PDF).

- ^ "Texas Coins Approved". Waco Times Herald. June 8, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Congressional Record, June 7, 1933, p. 5148" (PDF).

- ^ "Texas Coinage Bill Signed". Corsicana Daily Sun. June 16, 1933. p. 15. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Flynn 2008, p. 351.

- ^ Bowers 1991, pp. 267–269.

- ^ a b Vermeule 1971, p. 186.

- ^ Remy, Caroline; Levering, Jean L.; Branda, Eldon Stephen; Curlee, Kendall (July 19, 2023). "Coppini, Pompeo Luigi (1870–1957)". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Support of Texas Centennial Urged". Austin American. August 1, 1933. p. 10. Retrieved June 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Taxay 1967, pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b Swiatek & Breen 1981, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen 1981, p. 233.

- ^ Rochette, Ed (October 6, 1985). "Collectors Remember the Alamo". Newsday. p. 69. ProQuest 285372898. Retrieved July 9, 2024 – via Proquest.

- ^ Mehl 1937, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen 1981, p. 234.

- ^ Swiatek 2012, p. 236.

- ^ a b "Commemorative Half-Dollars On Sale Here". Pampa Daily News. December 30, 1934. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved July 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com. Page 7 here

- ^ "Ma Owns First Centennial Coin as Auction Ends". Austin American-Statesman. December 16, 1934. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved July 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com. Page 2 here

- ^ "Centennial Coins". Houston Post. December 30, 1934. p. 6. Retrieved July 2, 2024 – via Abilene Daily Reporter and Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Centennial 'Four-Bit' Piece Given Garner". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. March 3, 1935. p. 13. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coin Sale to Build Museum". The Amarillo Globe-Times. March 7, 1935. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Centennial Coins Sold". The Paris Times. February 28, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Adair, Anthony Garland (June 4, 1935). "Buying of New Coins to Help Museum Plans". McAllen Daily Press. p. 2.

- ^ "Legion Funds for Museum Are Growing". Pampa Daily News. April 1, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Official of Texas Still Has Only Two Children in Family". Shreveport Journal. June 14, 1935. p. 24. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bowers 1991, p. 270.

- ^ "Few W Texans Anxious to Pay $1 for 50 Cents". San Angelo Standard-Times. December 1, 1935. p. 10. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Coin Orders Soon". San Angelo Standard-Times. August 18, 1935. p. 21. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Government Moves to Coin More Half Dollars Texas Centennial Issue". Wichita Falls Times. November 12, 1935. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bowers 1991, p. 271.

- ^ "Centennial Coins Will Be Minted". Abilene Daily Reporter. December 12, 1935. p. 12. Retrieved July 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mehl 1937, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Bowers 1991, pp. 268–270.

- ^ a b c d e Swiatek & Breen 1981, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Senate hearing, p. iii.

- ^ Bowers 1991, pp. 248–249, 301–302.

- ^ "Texas University to have a Great Memorial Museum". The Hamlin Herald. February 14, 1936. p. 2. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knight, Hugh (February 16, 1936). "Coins". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 47. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "30,000 Texas Coins Ready for Disposal". The Philadelphia Inquirer. April 26, 1936. p. 18. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Midkiff, Morris (June 12, 1936). "30,000 Austin People Greet President Roosevelt". The Austin American. p. 1. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sale of Centennial Coins Being Offered Many State Points". Corsicana Daily Sun. July 22, 1936. p. 9. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Untitled". The Comanche Chief. May 29, 1936. p. 4. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Untitled". The Kerrville Times. April 9, 1936. p. 3. Retrieved July 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "First Unit of New Memorial Museum to be Ready Soon". Victoria Advocate. August 27, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved July 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Allred Praises Texas Memorial Museum". Wichita Falls Times. December 20, 1937. p. 2. Retrieved July 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Texas Memorial Museum Opens Doors to Public; Structure is Art Masterpiece". Clovis News-Journal. August 18, 1938. p. 12. Retrieved July 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1938 Centennial Coins Received". Austin American. January 22, 1938. p. 12. Retrieved July 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen 1981, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Swiatek 2012, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Bowers 1991, pp. 270–275.

- ^ Yeoman 2020, pp. 1083–1084.

Bibliography

- Bowers, Q. David (1991). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Bowers and Merena Galleries. ISBN 0-943161-36-3.

- Mehl, B. Max (1937). The Commemorative Coins of the United States. B. Max Mehl. OCLC 2872685.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, Georgia: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States: History, Art, Investment & Collection of America's Memorial Coinage (2nd ed.). Chicago: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins 1892-1954. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 0-668-04765-8.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York: Arco Publishing. LCCN 67-10696.

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (March 11, 1936). Coinage of commemorative 50-cent pieces. United States Government Printing Office.

- Vermeule, Cornelius Clarkson III (1971). Numismatic Art in America: Aesthetics of the United States Coinage. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3. SBN 674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2020). A Guide Book of United States Coins (Mega Red 5th ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4705-0.