Cepheus (constellation)

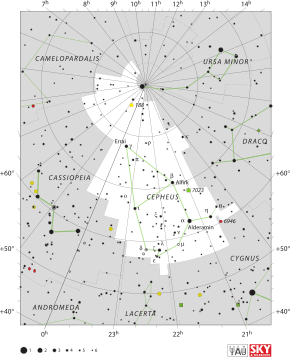

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Cep |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Cephei |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsiːfiəs/ or /ˈsiːfjuːs/; genitive /ˈsiːfiaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the King/King Cepheus |

| Right ascension | 20h 01m 56.4481s–09h 03m 19.7931s[1] |

| Declination | 88.6638870°–53.3532715°[1] |

| Area | 588 sq. deg. (27th) |

| Main stars | 7 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 43 |

| Stars with planets | 1 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 1 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | α Cep (Alderamin) (2.45m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | 0 |

| Bordering constellations | Cygnus Lacerta Cassiopeia Camelopardalis Draco Ursa Minor |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −10°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of November. | |

Cepheus is a constellation in the far northern sky, named after Cepheus, a king of Aethiopia in Greek mythology. It is one of the 48 constellations listed by the second century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 constellations in the modern times.

The constellation's brightest star is Alpha Cephei, with an apparent magnitude of 2.5. Delta Cephei is the prototype of an important class of star known as a Cepheid variable. RW Cephei, an orange hypergiant, together with the red supergiants Mu Cephei, MY Cephei, VV Cephei, V381 Cephei, and V354 Cephei are among the largest stars known. In addition, Cepheus also has the hyperluminous quasar S5 0014+81, which hosts an ultramassive black hole in its core, reported at 40 billion solar masses, about 10,000 times more massive than the central black hole of the Milky Way, making this among the most massive black holes currently known.[2][3]

History and mythology

Cepheus was the King of Aethiopia. He was married to Cassiopeia and was the father of Andromeda, both of whom are immortalized as modern day constellations along with Cepheus.[4]

Features

Alderamin, also known as Alpha Cephei, is the brightest star in the constellation, with an apparent magnitude of 2.51.[5] Gamma Cephei, also known as Errai, is the second-brightest star in the constellation, with an apparent magnitude of 3.21.[6] It is a binary star, made up by a orange giant or subgiant[7] and a red dwarf.[8] The primary component hosts one exoplanet, Gamma Cephei Ab (Tadmor).[9] Delta Cephei is a yellow-hued supergiant star 980 light-years from Earth and the prototype of the class of the Cepheid variables. It was discovered to be variable by John Goodricke in 1784. It varies between 3.5m and 4.4m over a period of 5 days and 9 hours. The Cepheids are a class of pulsating variable stars; Delta Cephei has a minimum size of 40 solar diameters and a maximum size of 46 solar diameters. It is also a double star; the primary star also has a wide-set blue-hued companion of magnitude 6.3.[10]

There are four red supergiants in the constellation that are visible to the naked eye. Mu Cephei is also known as Herschel's Garnet Star due to its deep red colour. It is a semiregular variable star with a minimum magnitude of 5.1 and a maximum magnitude of 3.4. Its period is approximately 2 years.[11] The star's radius has been estimated to be from 972 solar radii (4.52 AU)[12] to 1,420 solar radii (6.6 AU).[13] If it were placed at the center of the Solar System, it would possibly reach the orbit of Jupiter. The second, VV Cephei A, is a semiregular variable star, located approximately 5,000 light-years from Earth. It has a minimum magnitude of 5.4 and a maximum magnitude of 4.8,[14] and is paired with a blue main sequence star called VV Cephei B. The red supergiant primary is around 1,050 times larger than the Sun.[15] VV Cephei is also an unusually long-period eclipsing binary, but the eclipses, which occur every 20.3 years, are too faint to be observed with the unaided eye. The third, V381 Cephei Aa, is the faintest of all, at maximum magnitude 5.5.[14] It is part of a triple star system similar to VV Cephei,[16][17] and has a diameter 980 times that of the Sun.[18] The fourth, Zeta Cephei, is not as large as with a diameter less than 200 times that of the Sun;[19] however, its surface would lie between the orbits of Venus and Earth if placed at the center of the Solar System. Zeta Cephei has an apparent magnitude of 3.35, being the fourth-brightest star in the constellation.[13] All four stars have initial masses more than eight times that of the Sun and are accepted core-collapse supernova candidates.[20]

Nu Cephei is a blue supergiant similar to Deneb with an initial mass of over 20 solar masses. It belongs to the Cepheus OB2 stellar association along with Mu Cephei and VV Cephei, which have similar initial masses.[21]

There are several prominent double stars and binary stars in Cepheus. Omicron Cephei is a binary star with a period of 800 years. The system, 211 light-years from Earth, consists of an orange-hued giant primary of magnitude 4.9 and a secondary of magnitude 7.1. Xi Cephei is another binary star, 102 light-years from Earth, with a period of 4,000 years. It has a blue-white primary of magnitude 4.4 and a yellow secondary of magnitude 6.5.[11]

Krüger 60 is an 11th-magnitude binary star consisting of two red dwarfs. The star system is one of the nearest, being only 13 light-years away from Earth. It was once proposed as a possible home system for 2I/Borisov, the first accepted interstellar comet, but this was later rejected.[22]

Deep-sky objects

- NGC 188 is an open cluster that has the distinction of being the closest open cluster to the north celestial pole, as well as one of the oldest-known open clusters.

- NGC 6946 is a spiral galaxy in which ten supernovae have been observed, more than in any other galaxy. It is sometimes called the Fireworks Galaxy.[24][25]

- IC 469 is another spiral galaxy, characterized by a compact nucleus, of oval shape, with perceptible side arms.

- The nebula NGC 7538 is home to the largest-yet-discovered protostar.[26]

- NGC 7023 is a reflection nebula with an associated star cluster (Collinder 429); it has an overall magnitude of 7.7 and is 1,400 light-years from Earth. The nebula and cluster are located near Beta Cephei and T Cephei.[27]

- S 155, also known as the Cave Nebula,[28] is a dim and very diffuse bright nebula within a larger nebula complex containing emission, reflection, and dark nebulosity.

- The quasar 6C B0014+8120 is one of the most powerful objects in the universe, powered by a supermassive black hole which is as massive as 40 billion Suns.[29]

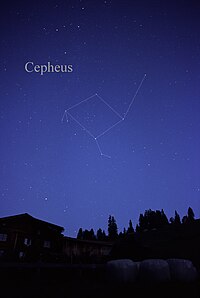

Visualizations

Cepheus is most commonly depicted as holding his arms aloft, praying for the deities to spare the life of Andromeda. He also is depicted as a more regal monarch sitting on his throne.[4]

Equivalents

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of the constellation Cepheus are found in two areas: the Purple Forbidden enclosure (紫微垣, Zǐ Wēi Yuán) and the Black Tortoise of the North (北方玄武, Běi Fāng Xuán Wǔ).

Namesakes

- USS Cepheus (AKA-18) and USS Cepheus (AK-265), United States Navy ships.

- Update 3.4 "Cepheus" of the videogame Stellaris[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Cepheus, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Ghisellini, G.; Ceca, R. Della; Volonteri, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; Tavecchi, F.; Foschini, L.; Tagliaferri, G.; Haardt, F.; Pareschi, G.; Grindlay, J. (2010). "Chasing the heaviest black holes in active galactic nuclei, the largest black hole". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 405 (1): 387. arXiv:0912.0001. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.405..387G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16449.x. S2CID 40214759. This paper does acknowledge the possibility of an optical illusion that would cause an overestimation of the mass.

- ^ Ghisellini, G.; Foschini, L.; Volonteri, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; Haardt, F.; Burlon, D.; Tavecchio, F.; et al. (14 July 2009). "The blazar S5 0014+813: a real or apparent monster?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. v2. 399 (1): L24 – L28. arXiv:0906.0575. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399L..24G. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2009.00716.x. S2CID 14438667.

- ^ a b Staal 1988, pp. 14–18

- ^ van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. Jr. (1995-11-01). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Hoffleit+, 1991)". VizieR Online Data Catalog: V/50. Bibcode:1995yCat.5050....0H.

- ^ Keenan, Philip C.; McNeil, Raymond C. (1989-10-01). "The Perkins Catalog of Revised MK Types for the Cooler Stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 71: 245. Bibcode:1989ApJS...71..245K. doi:10.1086/191373. ISSN 0067-0049. S2CID 123149047.

- ^ Neuhaeuser, Ralph; Mugrauer, Markus; Fukagawa, Misato; Torres, Guillermo; Schmidt, Tobias (February 2007). "Direct detection of exoplanet host star companion gamma Cep B and revised masses for both stars and the sub-stellar object". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 462 (2): 777–780. arXiv:astro-ph/0611427. Bibcode:2007A&A...462..777N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066581. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ "First Discoveries: Gamma Cephei A b". exoplanets.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 112–115.

- ^ a b Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Montargès, M.; Homan, W.; Keller, D.; Clementel, N.; Shetye, S.; Decin, L.; Harper, G. M.; Royer, P.; Winters, J. M.; Le Bertre, T.; Richards, A. M. S. (2019-05-01). "NOEMA maps the CO J = 2 - 1 environment of the red supergiant μ Cep". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 485: 2417–2430. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz397. ISSN 0035-8711.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Levesque, Emily M.; Massey, Philip; Olsen, K. A. G.; Plez, Bertrand; Josselin, Eric; Maeder, Andre; Meynet, Georges (August 2005). "The Effective Temperature Scale of Galactic Red Supergiants: Cool, But Not As Cool As We Thought". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (2): 973–985. arXiv:astro-ph/0504337. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..973L. doi:10.1086/430901. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b Samus, N. N.; Kazarovets, E. V.; Durlevich, O. V.; Kireeva, N. N.; Pastukhova, E. N. (2009-01-01). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+, 2007-2017)". VizieR Online Data Catalog. 1: B/gcvs.

- ^ Bauer, Wendy Hagen; Gull, Theodore R.; Bennett, Philip D. (2008-08). "SPATIAL EXTENSION IN THE ULTRAVIOLET SPECTRUM OF VV CEPHEI". The Astronomical Journal. 136 (3): 1312. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/3/1312. ISSN 1538-3881.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (2008-09-01). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 389: 869–879. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Halbedel, Elaine M. (1991-03-01). "Photometric Variability for the VV Cephei-Like Star HR 8164". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 103: 310. doi:10.1086/132820. ISSN 0004-6280.

- ^ Healy, Sarah; Horiuchi, Shunsaku; Molla, Marta Colomer; Milisavljevic, Dan; Tseng, Jeff; Bergin, Faith; Weil, Kathryn; Tanaka, Masaomi (2024-03-23). "Red Supergiant Candidates for Multimessenger Monitoring of the Next Galactic Supernova". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 529 (4): 3630–3650. doi:10.1093/mnras/stae738. ISSN 0035-8711.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Baines, Ellyn K.; Armstrong, J. Thomas; Clark, James H.; Gorney, Jim; Hutter, Donald J.; Jorgensen, Anders M.; Kyte, Casey; Mozurkewich, David; Nisley, Ishara; Sanborn, Jason; Schmitt, Henrique R.; Belle, Gerard T. van (October 2021). "Angular Diameters and Fundamental Parameters of Forty-four Stars from the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (5): 198. arXiv:2211.09030. Bibcode:2021AJ....162..198B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac2431. ISSN 1538-3881.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay, Mainak; Lunardini, Cecilia; Timmes, F. X.; Zuber, Kai (2020-08-01). "Presupernova neutrinos: directional sensitivity and prospects for progenitor identification". The Astrophysical Journal. 899 (2): 153. arXiv:2004.02045. Bibcode:2020ApJ...899..153M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab99a6. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Humphreys, R. M. (1978-12-01). "Studies of luminous stars in nearby galaxies. I. Supergiants and O stars in the Milky Way". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 38: 309–350. doi:10.1086/190559. ISSN 0067-0049.

- ^ Dybczyński, Piotr A.; Królikowska, Małgorzata; Wysoczańska, Rita (2019-11-26). "Kruger 60 as a home system for 2I/Borisov -- a case study". arXiv:1909.10952 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ "Smoky Shells". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Michaud, Peter (1 January 2015). "Gemini Observatory Welcomes 2005 with Release of Galactic Fireworks Image". NASA. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- ^ Boen, Brooke (20 May 2015). "NGC 6946: The 'Fireworks Galaxy'". NASA. Retrieved 2016-12-08.

- ^ Sandell, Göran; Wright, Melvyn (2010). "A Detailed Study of the Accretion Disk Surrounding the High-Mass Protostar NGC 7538 S". The Astrophysical Journal. 715 (2): 919–938. arXiv:1004.0643v1. Bibcode:2010ApJ...715..919S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/715/2/919. S2CID 119284322.

- ^ Levy 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Mobberley, M. (9 March 2017). The Caldwell Objects and How to Observe Them. Springer. ISBN 9781441903266.

- ^ Ghisellini, Gabriele; Foschini, Luigi; Volonteri, Marta; Ghirlanda, Giancarlo; et al. (14 Jul 2009). "The blazar S5 0014+813: a real or apparent monster?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 399 (1): L24 – L28. arXiv:0906.0575. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399L..24G. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2009.00716.x. S2CID 14438667. 17:53:24 GMT.

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

- Staal, Julius D.W. (1988), The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars (2nd ed.), The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, ISBN 0-939923-04-1