Dick Butkus

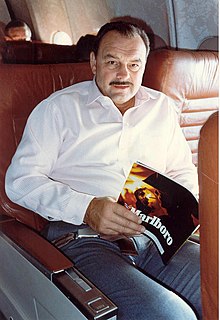

Butkus c. 1995 | |||||||

| No. 51 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Linebacker | ||||||

| Personal information | |||||||

| Born: | December 9, 1942 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | ||||||

| Died: | October 5, 2023 (aged 80) Malibu, California, U.S. | ||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) | ||||||

| Weight: | 245 lb (111 kg) | ||||||

| Career information | |||||||

| High school: | Chicago Vocational (IL) | ||||||

| College: | Illinois (1962–1964) | ||||||

| NFL draft: | 1965 / round: 1 / pick: 3 | ||||||

| AFL draft: | 1965 / round: 2 / pick: 9 | ||||||

| Career history | |||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||

| |||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||

| |||||||

Richard Marvin Butkus (December 9, 1942 – October 5, 2023) was an American football linebacker, sports commentator, and actor. He played football for the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) from 1965 to 1973. He was invited to eight Pro Bowls in nine seasons, named a first-team All-Pro five times, and was twice recognized by his peers as the NFL's Defensive Player of the Year. Butkus was renowned as a fierce tackler and for the relentless effort with which he played. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most intimidating linebackers in professional football history.

Butkus was born in Chicago and played his entire football career in his home state of Illinois, which began at Chicago Vocational High School. He was a linebacker and a center for the Illinois Fighting Illini. He was a twice consensus All-American, and he led the Illini to a Rose Bowl victory in 1963 and was deemed the most valuable player in the Big Ten Conference. Butkus was named college football's Lineman of the Year in 1964. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1983.

Butkus was selected by the Bears as the third overall pick in the 1965 NFL draft. He soon established himself as a ball hawk with his penchant for forcing turnovers. During his NFL career, he intercepted 22 passes and recovered 27 fumbles (a record when he retired),[a] and he was responsible for causing many more fumbles with his jarring tackles. His tackling ability earned him both admiration and trepidation from opposing players.[1] In 2009, the NFL Network named Butkus the most feared tackler of all time.

Butkus is credited with having defined the middle linebacker position and is still viewed as the "gold standard by which other middle linebackers are measured".[2] In his honor, the Butkus Award recognizes American football's most outstanding linebacker. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1979, and his No. 51 jersey was retired by the Bears. Following his playing career, Butkus worked in acting, sports commentary, and celebrity endorsement. He was active in philanthropy through the Butkus Foundation, which manages various charitable causes.

Early life

Butkus was born in Chicago, the youngest of eight children, and first to be born in a hospital. He was a very large baby, weighing 13 pounds 6 ounces (6.1 kg) at birth.[3] His father John, a Lithuanian immigrant to Ellis Island who spoke broken English, was an electrician and worked for the Pullman-Standard railroad car manufacturing company. His mother, Emma, worked 50 hours a week at a laundry.[4] Butkus grew up in the Roseland neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. He was a fan of the Chicago Cardinals of the National Football League (NFL) and attended their games at Comiskey Park. His older brother Ron played football for three colleges and tried out for the Cardinals before quitting due to a bad knee.[5] For four years starting at age 15, Butkus worked with his four brothers as a mover.[6]

Butkus played high school football as a fullback, linebacker, punter, and placekicker for coach Bernie O'Brien at Chicago Vocational High School. He averaged five yards per carry as a fullback, but preferred playing linebacker, where he made 70 percent of his team's tackles.[4] In Butkus's first year on the varsity team, Chicago Vocational surrendered only 55 points in eight games.[5] In 1959, he was the first junior to be honored by the Chicago Sun-Times as Chicago's high school player of the year.[5] Injuries limited his play as a senior, but he was still heavily recruited by colleges to play football.[3]

In the summer of 1960, Butkus was the starting catcher on a Chicago Park District baseball team known as the Sundodgers. An article in the Daily Calumet credits Butkus with having driven in all of the Sundodgers' runs in a loss in having hit a home run to center field.[7]

College career

Butkus chose to attend the University of Illinois, and played center and linebacker from 1962 through 1964 for the Illinois Fighting Illini football team. He initially wanted to play for the Notre Dame Fighting Irish, however the team frowned upon married players at the time. In his first year on the varsity team, he was named to the 1962 All-Big Ten Conference football team as the third-team center by the Associated Press (AP) and second-team center by United Press International (UPI).[8][9] In 1963, Illinois compiled an 8–1–1 record and defeated Washington in the 1964 Rose Bowl. Butkus was named the team's most valuable player for the season, and was awarded the Chicago Tribune Silver Football as the Big Ten's most valuable player.[10] He was a unanimous choice as a center for the 1963 College Football All-America Team, earning first-team honors from all seven major selectors.[11]

As a senior in 1964, Butkus was named the team's co-captain along with safety George Donnelly.[12] UPI deemed Butkus college football's Lineman of the Year for 1964,[13] and he was named the player of the year by the American Football Coaches Association and The Sporting News.[14] For the second consecutive season he was deemed the Illini's most valuable player. He was chosen for the 1964 All-America team by five of the six major selectors. In a cover story for Sports Illustrated that season, sportswriter Dan Jenkins remarked, "If every college football team had a linebacker like Dick Butkus of Illinois, all fullbacks soon would be three feet tall and sing soprano."[15] Butkus also finished sixth in Heisman Trophy balloting in 1963 and third in 1964, rare results both for a lineman and a defensive player.[16] According to statistics kept by the university, he completed his college career with 374 tackles: 97 in 1962, 145 in 1963, and 132 in 1964.[17]

Professional career

Butkus was the third overall selection of the 1965 NFL draft, taken by the Chicago Bears, and also in the second round of the 1965 AFL draft by the Denver Broncos of the American Football League.[18] After several days of recruiting by both the teams and leagues, his decision to sign with the Bears was viewed as a major victory for the NFL.[19] Although the Bears offered him less money than the Broncos, playing for his hometown team and coach George Halas was more enticing.[20] His rookie contract was worth $200,000.[21] Along with fellow future Hall of Famer Gale Sayers (fourth overall), Butkus was one of three first-round picks for the Bears that NFL draft. The pick they used for Butkus had been acquired in a trade with the Pittsburgh Steelers.[22]

1965–1970

Succeeding hall of famer Bill George at middle linebacker, Butkus made an immediate impact as a rookie in 1965.[23] He established himself as a ball hawk by intercepting five passes and recovering six opponents' fumbles, and he was also credited unofficially with having forced six fumbles.[24] Against the New York Giants on November 28, he intercepted a pass and recovered a fumble, and was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Week by the AP for the first of four times in his career.[25]

He finished third in balloting for the AP's rookie of the year award, behind Sayers and Ken Willard of the San Francisco 49ers, with AP sportswriter Jack Hand remarking that Butkus would have certainly won if there was a separate award for defenders.[b][26] He was named a first-team All-Pro by the AP and was invited to his first of eight straight Pro Bowls.[18]

In 1966, Butkus was named the second-team middle linebacker on the All-Pro teams of the AP, UPI, Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA), and New York Daily News, with each selector placing him behind Ray Nitschke of the Green Bay Packers.[27] He reclaimed the first-team spot on the UPI and NEA teams in 1967, the AP team in 1968, and the Daily News team in 1969, all of which he occupied through the 1970 season.[18]

Butkus scored the first points of his career in 1969, when he tackled Steelers' quarterback Dick Shiner in the end zone for a safety on November 9. He also recorded 25 tackles in the game, and for his efforts was recognized as the NFL Defensive Player of the Week by the AP.[28] That 38–7 win for the Bears was their only one of the season; they finished with a 1–13 record, which was the worst in franchise history. Additionally, Butkus's five-year contract had reached its end. A number of Bears players, including Butkus, expressed interest in being traded or cut by the team,[29] but he signed a multi-year contract extension prior to the 1970 season to remain in Chicago.[30] The contract raised his salary from $50,000 per year to around $80,000 to $100,000 per year.[21]

Despite the ineptitude of the Bears as a team, Butkus developed a reputation around the league as one of its best players. In both 1969 and 1970, he was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Year by the NEA, which was voted on by NFL players.[31][32] He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in September 1970 with the caption, "The Most Feared Man in the Game".[33] A panel of NFL coaches that year named Butkus the player they would most prefer to start a team with if they were building one from the ground up.[34]

1971–1973

Prior to the 1971 season, Butkus underwent preventive surgery on his right knee; he had torn ligaments in high school, but was able to continue playing due to strong muscles compensating for the injury.[35] In the Bears' first ever game at Soldier Field on September 19 against the Pittsburgh Steelers, Butkus turned in a great performance. With the Bears down 15–3 in the 4th, Butkus picked off quarterback Terry Bradshaw twice. Butkus did intercept a pass from Bradshaw a third time but was called back by a penalty against the Bears. In the final minutes with the Bears down 15–10, Butkus forced a fumble on running back Warren Bankston which was recovered by Bears defensive end Ed O'Bradovich on the Steelers' 12-yard line. The turnover led the Bears to score and win 17–15. In 1971, he recorded 117 tackles and four interceptions, leading the Bears in both statistics.[36] On November 14, he scored a point; in the closing minutes of a game against the Washington Redskins, the score was tied at 15 and the Bears had lined up to kick an extra point. The snap went over the head of holder Bobby Douglass, who then raced back to retrieve the ball and looked to pass it. Butkus, who was playing as a blocking back, ran into the end zone and leapt to receive the pass for the winning score.[c][37][38] Butkus later called the play his favorite of his career.[34] Despite the statistical output, for the first time since 1966 Butkus was not named to a major All-Pro first-team, instead earning second-team honors from the NEA and Pro Football Writers Association.[18]

Butkus sparked controversy in 1972 with the release of Stop-Action, a memoir describing the final week of the 1971 season. The Bears had lost their final five games in 1971, and Butkus used the memoir as an outlet for his frustrations and grievances. In particular, he harshly criticized the Detroit Lions organization, saying, "I think they are a lot of jerks, from the owner, the general manager, the coach on down... If we were voting for a jerk team or organization they'd have my vote all the way."[39] The Lions responded with a 38–24 win over the Bears in Week 3 of 1972.[40] After the game Lions linebacker Mike Lucci, whom Butkus had labeled a "crybaby", denied that the book had any bearing on the game's outcome, but told reporters, "Butkus should just keep his mouth shut and play football." Butkus, who was notoriously surly with reporters, also denied any connection and accused the media of sensationalism.[41] Bears teammate Gale Sayers later said he did not like the book, feeling Butkus was above such name-calling.[42] The season as a whole was another productive one for Butkus, who reclaimed the first-team middle linebacker spot on the major All-Pro teams and was invited to his final Pro Bowl.[18]

Early in the first quarter against the Houston Oilers in 1973, Butkus pounced on a fumble in the end zone for the only touchdown of his career. Houston tight end Mack Alston accused Butkus of intimidating the officials, saying he "grabbed the ball and started yelling 'touchdown, touchdown,'" after which "the officials looked at each other, shrugged their shoulders and called it a touchdown."[43] His season was cut short after nine games by a lingering right knee injury, which he had been playing through for years, but was further aggravated after it gave out in Week 5 against the Atlanta Falcons.[44] Prior to the 1974 season an orthopedic surgeon told him, "I don't know how a man in your shape can play football or why you would even want to."[45] The injury ultimately forced him to retire in May 1974 at age 31.[46]

Lawsuit against Bears

Butkus's retirement came with four years remaining on a five-year contract with the Bears, which was to pay him $115,000 per year through 1977. It came with a no-cut, no-trade clause, and was payable even if surgery was needed. The contract also promised necessary medical and hospital care which, according to Butkus, the Bears neglected to provide him, causing irreparable damage to his knee. The Bears then told him he would not be paid if he could not play. Butkus filed suit against the Bears' team doctor in May 1974 asking for $600,000 in compensatory damages and $1 million in punitive damages.[47][48] It was eventually settled out of court when the Bears agreed to pay Butkus the full value of his contract. The episode caused a rift between Butkus and Bears owner George Halas, and the two did not speak for the next five years.[49]

Profile and reputation

Dick was an animal. I called him a maniac. A stone maniac. He was a well-conditioned animal, and every time he hit you, he tried to put you in the cemetery, not the hospital.[1]

— Deacon Jones, Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive end

Standing 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) tall and weighing 245 pounds (111 kg), Butkus was a large linebacker for the era in which he played football.[16] This size was a common trait in his family, as all four of his brothers and his father each stood over six feet tall and weighed over 200 pounds. He was also diligent with his conditioning. In high school he would push a car up and down a street to strengthen his legs,[50] and in college he developed a routine of running at trees and dodging them to emulate avoiding blockers.[51] Despite his size, he also had the speed and agility to make tackles from sideline to sideline and cover tight ends and running backs on pass plays.[52]

Hall of Famer Bill George, whom Butkus succeeded as the Bears' middle linebacker, said, "The first time I saw Butkus, I started packing my gear. I knew my Bear days were numbered. There was no way that guy wasn't going to be great."[53]

Consistently cited as one of football's meanest, toughest, and most feared players, Butkus was renowned for his intimidating profile and style of play.[21][15] He was known to snarl at the opposition prior to plays.[54] Quarterbacks would complain of Butkus biting them in pileups.[55] Lions tight end Charlie Sanders recalled Butkus poking him in the eyes with his fingers through his face mask.[56] He once intercepted a pass from Minnesota Vikings quarterback Fran Tarkenton near the goal line, and instead of taking the ball into the end zone for an easy touchdown, he took aim at Tarkenton to run him over.[6] When asked by a reporter if he was as mean as the rumors suggested, Butkus replied, "I wouldn't ever go out to hurt anybody deliberately. Unless it was, you know, important—like a league game or something."[57]

He played angry, often "manufacturing" things to make him mad, because he felt it gave him a competitive edge.[52][58] After the Bears lost to the Lions in their first matchup of 1969, Lions rookie running back Altie Taylor told reporters that Butkus was overrated. The next time the teams played that season, Butkus responded by chasing Taylor out of bounds after a play and causing him to jump into the stands at Wrigley Field.[59][60]

Butkus became most noted for his tackling ability, and the ferocity with which he tackled opponents. He was named the most feared tackler of all time by the NFL Network in 2009.[61] Once during practice, he hit a metal football sled so hard that he crumpled it and left a piece of it dangling off.[53] "Tackling wasn't good enough," recalled former Bears defensive end Ed O'Bradovich. "Just to hit people wasn't good enough", he continued. "He loved to crush people."[59] Butkus is credited with 1,020 tackles in his NFL career.[16][62][63]

Butkus recovered 27 fumbles in his career,[a] an NFL record at the time of his retirement.[16] One of his greatest strengths was his ability to rip the ball from a ball carrier's hands. Although not an official statistic at the time, it has been noted that Butkus would certainly be one of the all-time leaders in forced fumbles.[59][34]

In spite of all he could do on defense, Butkus could not turn the Bears into a winner: during his time there, the team only won 48 games, lost 74, and tied 4.[66]

Legacy and honors

USA Today called Butkus the "gold standard by which other middle linebackers are measured."[2] Although not the creator of the middle linebacker position—which is credited to his predecessor Bill George—Butkus is recognized as having defined the role.[1][62] He is also recognized for having set the benchmark for the success of Bears middle linebackers, which continued with Mike Singletary and Brian Urlacher.[67] Hall of Fame running back Earl Campbell, known for his hard-hitting running style, cited Butkus as his hero growing up.[68]

After his university years, Butkus continued to receive recognition for his college career. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1983.[69] His No. 50 jersey is one of only two retired by the Illinois Fighting Illini football program, the other being the No. 77 of Red Grange,[70] and he was an inaugural inductee into the Illinois Athletics Hall of Fame in 2016.[71] Butkus was named to the Walter Camp Football Foundation's All-Century Team in 1999, compiled to honor the best college players of the 20th century.[72] In November 2017, Illinois announced it would erect a statue of Butkus on campus to overlook a future football performance center.[73]

Butkus was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1979, his first year of eligibility.[74] The Hall's voters also named him to the NFL's 1960s All-Decade Team and 1970s All-Decade Team, deeming him one of the best players of both decades.[65] On October 31, 1994, the Bears retired Butkus's No. 51 jersey along with Sayers's No. 40 jersey during a ceremony at Soldier Field.[75] In 2004, a sculpture featuring Butkus, Halas, and seven other former Bears greats was unveiled at Soldier Field.[49]

Butkus has been repeatedly ranked among the top players in NFL history, being named the ninth-best player in NFL history by The Sporting News in 1999,[76] the tenth-best by the NFL Network in its The Top 100: NFL's Greatest Players series in 2010,[77] and the eighth-best by the New York Daily News in 2014.[78] In 2017, NFL senior analyst Gil Brandt ranked Butkus as the third greatest linebacker of all time, behind Derrick Thomas and Lawrence Taylor.[79] He was also selected the 70th greatest athlete of the 20th century by ESPN.[80] In 1994, he was named to the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team, compiled to recognize the best players of the NFL's first 75 years as adjudged by NFL officials and media personnel.[81] In 2019, Butkus was named to the NFL 100th Anniversary All-Time Team.[82]

Butkus was ranked No. 1 on NFL Top 10: Most Feared Tacklers when the episode aired in 2008.[83]

Honoring his contributions to Chicago sports, Butkus was inducted into the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame in 2008.[84] On August 24, 2013, he was inducted into the National Lithuanian American Hall of Fame.[85] In 2018 Butkus was inducted as a laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln, the state's highest honor, by the Governor of Illinois.[86]

In 1985, the Downtown Athletic Club of Orlando, Florida, created the Butkus Award, which is given annually to the most outstanding linebacker at the high school, college, and professional levels as chosen by a nationwide panel of 51 coaches and sportswriters.[87] Butkus sued the Downtown Athletic Club for rights to the award in 2007, which it relinquished after a yearlong court battle. It has since been presented by the Butkus Foundation.[88]

As an homage, actor Sylvester Stallone named his pet Bullmastiff Butkus after the dog ate a security blanket. He decided to name him after "possibly the fiercest football player in history".[89] The dog later starred alongside Stallone in the Rocky film series.[1]

Film and television career

After his career as a player, Butkus became a celebrity endorser, broadcaster, and actor.[90][91] He appeared in films such as The Longest Yard (1974),[92] Cry, Onion! (1975),[93] Mother, Jugs & Speed (1976),[94] Gus (1976),[95] Superdome (1978),[95] Cracking Up (1983),[94] Johnny Dangerously (1984),[94] Hamburger: The Motion Picture (1986),[94] The Stepford Children (1987),[95] Spontaneous Combustion (1990),[95] Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990),[90][96] Necessary Roughness (1991),[90] and Any Given Sunday (1999),[90] and as a regular character on TV shows such as Blue Thunder,[90] My Two Dads,[90] MacGyver,[90] and Hang Time,[90] as well as in a guest role on Murder, She Wrote.[97] He portrayed himself in both the critically acclaimed TV movie Brian's Song (1971)[98] and the 2002 comedy Teddy Bears' Picnic.[90] Butkus portrayed Officer Alvin Dimsky in Cass Malloy,[99] the 1982 CBS pilot for what later became the syndicated situation comedy She's the Sheriff, and also made cameo appearances in episodes of several television shows.[90][91]

Butkus endorsed Prestone, a brand of antifreeze, in a commercial during Super Bowl IV in 1970. The ad marked the first highly successful celebrity endorsement in Super Bowl advertising.[100] Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, Butkus appeared alongside fellow former NFL star (and later Blue Thunder co-star) Bubba Smith in a series of ads for Miller Lite, which were released to high acclaim.[101] In 1985, he was a pitchman for Echo Tools, a producer of outdoor power equipment.[102] In the 1990s, Butkus promoted the "Qwik-Cook Grill", a grill using newspaper as its main fuel.[103]

Butkus returned to the Bears as a color analyst on radio broadcasts in 1985, teaming with first-year play-by-play man Wayne Larrivee and former St. Louis Cardinals quarterback Jim Hart. He was hired as the replacement for Jimmy "The Greek" Snyder on CBS's pregame show The NFL Today in 1988,[104] serving as an analyst through 1989. He was named as head coach of the XFL's Chicago Enforcers franchise, but was replaced by coach Ron Meyer for the league's only season in 2001.[103] Instead, Butkus served as the league's director of competition and, during the second half of the season, a color commentator for the league's regional telecasts.[105]

In 2005, as part of the ESPN reality series Bound for Glory, Butkus served as head football coach of Montour High School in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.[106] He coached the team to a 1–6 record before departing with two games remaining in the season, saying he had fulfilled his contract for the show.[107]

Personal and later life

Butkus married his high school sweetheart, Helen Essenberg, in 1963 while they were students at the University of Illinois.[108][56] After his retirement, Butkus moved to Florida, and later to Malibu, California. He was an avid fan and frequent media image for the Bears.[15]

Butkus had three children: Ricky, Matt, and Nikki.[109] Matt played college football for the USC Trojans as a defensive lineman, and joined his father in philanthropic activities.[110][111] Butkus's nephew Luke Butkus has been an assistant coach in the NFL for the Bears, Seattle Seahawks, and Jacksonville Jaguars, he also coached for the University of Illinois, his alma mater, and as of 2023 is the offensive line coach for the Green Bay Packers.[112][113] Butkus's grandson Ian Parish plays volleyball for the UCLA Bruins.[114]

Injuries sustained during Butkus's playing career compounded with time. He had his knee replaced with a metal unit. An osteotomy left him with one leg 1.5 inches shorter than the other, which affected his hips, back, and neck. Around 2002, nerve damage in his spine caused him to develop foot drop. He lost strength in his hands, needing both to lift a coffee cup.[6] Still, Butkus maintained that football had a largely positive impact on his life, and that its benefits should not be overlooked.[115]

In August 2001, Butkus underwent quintuple bypass surgery to remove blockages in his arteries. After the surgery, he co-authored a book titled The OC Cure For Heart Disease with Lawrence J. Santora, the doctor who performed the procedure.[116]

Butkus died in his sleep at his home in Malibu, California, on October 5, 2023, at the age of 80.[117] The cause of death was a stroke, with atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis, and hypercholesterolemia listed as underlying causes.[118] His death came hours before the Bears were scheduled to play a Thursday Night Football game against the Washington Commanders. The Commanders held a moment of silence prior to the game.[119][120]

Philanthropy

Through The Butkus Foundation, Butkus has supported many charitable causes. The foundation was formed to manage the receipt and disbursement of funds for his charitable causes. These include:

- The Butkus Award, instituted in 1985, is one of the elite individual honors in football. The Butkus Foundation takes stewardship of the award recognizing athletic achievement and service to the community while honoring the nation's best high school, college, and professional linebackers. An independent selection committee is composed of 51 people, including professional, college, and high school scouts, and sports journalists.[87]

- The Dick Butkus Center for Cardiovascular Wellness is a nonprofit organization in Orange County, California, with a cardiac screening program that uses specialized testing to help identify those at risk of heart disease and sudden cardiac death.[121]

- The I Play Clean Campaign addresses the issue of steroids among high school athletes. The campaign educates and encourages high school athletes to train and eat well, without resorting to illegal steroids and performance-enhancing products.[122]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d Mullin, John (November 8, 2016). "Bears Classics: Dick Butkus Profiles the Standard for MLB Greatness". CSN Chicago. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Davis, Nate (November 4, 2010). "Who is NFL's greatest player ever? NFL Network reveals No. 1 Thursday night". USA Today. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Nelson, Murry R. (2013). American Sports: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-0313397530. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Pompei 2012, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Acocella, Nick (November 19, 2003). "Butkus was ferocious for struggling Bears". ESPN. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Telander, Rick (July 12, 2004). "Forever Growlin'". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 101, no. 2. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ "Tops Have Busy Weekend of Ball". The Daily Calumet (Ill.). June 15, 1960. p. 8. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1962 All-Big Ten Teams". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. November 27, 1962. p. 24. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ^ "Pick Big Ten All-Star Squad". Galesburg Register-Mail. United Press International. November 27, 1962. p. 12. Retrieved June 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dick Butkus Named MVP By Tribune". Freeport Journal-Standard. December 23, 1963. p. 13. Retrieved June 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, Lew (December 29, 1963). "Four Unanimous Choices". The Lawton Constitution. p. 11. Retrieved June 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Liska, Jerry (September 15, 1964). "Like a Rich Banker, Pete Elliott Has Gilt-Edge Assets At Illinois". Mt. Vernon Register-News. Associated Press. p. 8. Retrieved June 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dick Butkus Top Lineman". Valley Morning Star. United Press International. December 10, 1964. p. 10. Retrieved June 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bradley, Ken (December 16, 2014). "Sporting News all-time College Football Players of the Year". Sporting News. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c Rosenthal (December 7, 2017). "As Dick Butkus turns 75, Bears fans can embrace 51, who's more than media image". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Dick Butkus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ "Illinois: The Record Book" (PDF). University of Illinois. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Dick Butkus Stats". Pro Football Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Rathet, Mike (December 3, 1964). "Butkus Will Sign With Bears Today". Times Daily. Associated Press. p. 22. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "Butkus Takes Lesser Sum of Money To Play for Chicago". Dixon Evening Telegraph. Associated Press. December 4, 1964. p. 11. Retrieved August 13, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Eubanks, Lon (September 13, 1970). "Bear linebacker Butkus monster on Sunday". Southern Illinoisan. p. 45. Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pierson, Don (April 16, 1989). "Bears Didn't Blow It The Last Time They Had 3 First-rounders". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Cosgrove, Ben (December 3, 2013). "Dick Butkus in 1965: The Baddest Rookie the NFL Has Ever Seen". Time. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ^ "Dick Butkus Proving Budding Football 'Thief'". News-Journal. December 19, 1965. p. 36. Retrieved June 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hand, Jack (December 1, 1965). "Butkus Defensive Player Of Week". Anderson Daily Bulletin. Associated Press. p. 19. Retrieved August 13, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hand, Jack (December 22, 1965). "Chicago's Gale Sayers Named Rookie of Year; Polls All But 7 Votes". The Post-Crescent. Associated Press. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1966 NFL All-Pros". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Bears' Star Dick Butkus Selected Best On Defense". Fond du Lac Commonwealth Reporter. Associated Press. November 13, 1969. p. 39. Retrieved July 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Virgil Carter's Outburst Draws Stiff Fine from Chicago Bears". Great Bend Tribune. Associated Press. December 17, 1969. p. 11. Retrieved July 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Chicago Bears Sign Butkus To Multi-Year Pact". Anderson Herald. United Press International. May 31, 1970. p. 20. Retrieved July 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Butkus Beats Out All Other 'Front Four'". Pampa Daily News. Newspaper Enterprise Association. December 22, 1969. p. 4. Retrieved July 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (January 10, 1971). "Dick Butkus Named NFL's Defensive Player Of Year". Post-Herald and Register. Newspaper Enterprise Association. p. 22. Retrieved July 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McDill, Kent (2013). 100 Things Bears Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Triumph Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1617495779. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Bears in the Hall – Dick Butkus". Chicago Bears. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ^ "Surgery slated for Dick Butkus". Star-News. United Press International. January 28, 1971. p. 1-D. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Freedman 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Lowitt, Bruce (November 15, 1971). "Bears Nip Redskins, 16–15 On Butkus' Conversion Grab". The Journal News. Associated Press. p. 23. Retrieved July 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Freedman 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Olmert, Michael (October 16, 1972). "In 'Stop-Action,' the Bears' Dick Butkus may have taken his title too seriously". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 37, no. 16. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Angry Lions Smash Bears, Butkus 38–24". The Times Recorder. United Press International. October 2, 1972. p. 10. Retrieved July 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Smith, John (October 3, 1972). ""Back off" Dick Butkus". Belvidere Daily Republican. p. 5. Retrieved July 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Claus, Jimmy (October 5, 1972). "Sporting Around". The Terre Haute Tribune. p. 31. Retrieved July 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bears Find Someone To Pick On In Oilers". Freeport Journal-Standard. Associated Press. October 29, 1973. p. 13. Retrieved August 1, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dick Butkus' knee is worse than ever". The Post-Crescent. Associated Press. October 20, 1973. p. 7. Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nightingale, Dave (February 3, 1974). "Dick Butkus' knee—almost beyond repair". The Billings Gazette. p. 47. Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bears' Dick Butkus Retires". York Daily Record. United Press International. May 21, 1974. p. 17. Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Butkus Sues Bears for $1.6 Million, Charging Breach of Contract". The New York Times. May 30, 1974. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ Rollow, Cooper (May 30, 1974). "Butkus sues Bears for 1.6 million". Chicago Tribune. p. 1, section 3. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Pompei 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Gershman, Michael (1996). "Dick Butkus: Born to Play Football" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. 18 (2). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "Illini Center Dodges The Trees". Mt. Vernon Register-News. September 15, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved June 27, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Dick Butkus Bio". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Chicago Tribune 2015, p. 128.

- ^ Wojciechowski, Gene (January 25, 2012). "Toughness defined". ESPN. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Murray, Jim (May 23, 1976). "Name Inspired Terror". News-Journal. p. 27. Retrieved August 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Jones, Robert F. (September 21, 1970). "Nobody thinks I can talk". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 2015, p. 130.

- ^ Magee, Jerry (August 30, 1970). "Dick Butkus— 'I Personally Don't Like Anybody'". The San Bernardino County Sun. p. 21. Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Rand, Jonathan (2006). 300 Pounds of Attitude: The Wildest Stories And Craziest Characters The NFL Has Ever Seen. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 88–89. ISBN 1461749824. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Pompei 2012, p. 2.

- ^ "Top Ten Most Feared Tacklers: Dick Butkus". National Football League. January 7, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Center, Bill (January 12, 2013). "Prototype Butkus still No. 1 among NFL linebackers". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "ESPN Chicago Hall of Fame". ESPN. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Freedman 2006, p. 2.

- ^ a b Mayer, Larry (November 8, 2016). "Butkus featured on 'Bears Classics'". Chicago Bears. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Hopkins, Doc (March 22, 2013). "Chicago Bears Breakdown: The Best 8 Players in Team History". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ Isaacson, Melissa (August 11, 2011). "Bears' legacy deep up the middle". ESPN. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ Peter, Josh (January 31, 2017). "NFL legend Earl Campbell still hits hard, compares current NFL to wrestling". USA Today. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ "Simpson, Cannon head Hall of Fame list". The Salina Journal. United Press International. February 11, 1983. p. 19. Retrieved August 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Asmussen, Bob (September 1, 2003). "Grabowski, Howard join Butkus, Grange on stadium scoreboard". The News-Gazette. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Illini start sports Hall of Fame, Dick Butkus in 1st class". The Washington Times. Associated Press. October 27, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Walter Camp Football Foundation All-Century Team". Tallahassee Democrat. December 29, 1999. p. 24. Retrieved August 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ryan, Shannon (November 20, 2017). "Illinois to build Dick Butkus statue". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Butkus, Unitas among grid Hall of Fame picks". The Pantagraph. Associated Press. January 30, 1979. p. 11. Retrieved August 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul (October 22, 1994). "Richly Deserved Retirement For Butkus, Sayers Numbers". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ "Sporting News Top 100 Football Players". Democrat and Chronicle. August 15, 1999. p. 3D. Retrieved November 10, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barall, Andy (November 5, 2010). "Jim Brown Should Be No. 1, but What About Most Underrated?". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Myers, Gary (December 3, 2014). "NFL Top 50: Jim Brown is best player in league history, edges Giants' Lawrence Taylor in Daily News' rankings (Nos. 1–10)". Daily News. New York. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Brandt, Gil (June 30, 2017). "Gil Brandt's greatest NFL linebackers of all time". National Football League. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Top N. American athletes of the century". ESPN. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ "Very Best of the NFL". Detroit Free Press. August 24, 1994. p. 1D. Retrieved November 10, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mayer, Larry (November 29, 2019). "Butkus, Atkins, Hewitt named to NFL All-Time Team". chicagobears.com. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Stinson, Scott (April 7, 2012). "Scott Stinson: NFL sends mixed messages on violent hits". National Post. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "Self, Sayers to Hall of Fame". The Topeka Capital-Journal. September 26, 2008. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ "Football legends, actress to be inducted into Lithuanian Hall of Fame in Lemont". Suburban Life Media. August 20, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Gov. Rauner announces recipients of 2018 Order of Lincoln award" (PDF). illinois.gov. Office of the Governor. September 15, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "College football: 2016 Butkus Award preseason watch list announced". NCAA.com. July 18, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Schmadtke, Alan (April 29, 2008). "Downtown Athletic Club of Orlando relinquishes rights to the Dick Butkus Award". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Shepatin, Matthew (2009). "Then Madden Said to Summerall. . .": The Best NFL Stories Ever Told. Triumph Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-1617491986. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hernandez, Victoria; Henderson, Cydney. "Dick Butkus wasn't just a Chicago Bears legend. He became a busy actor after football". USA Today. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Nelson, Mark (October 6, 2023). "Remembering Dick Butkus and the XFL". XFL News and Discussion. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Browning, Matt; Browning, Matthew A. (September 15, 2021). The Definitive "Golden Girls" Cultural Reference Guide. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-6337-6.

- ^ Stewart, John (1994). Italian film: a who's who. McFarland. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-89950-761-3.

- ^ a b c d LuKanic, Steven A. (1991). Film actors guide. Lone Eagle Publ. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-943728-38-4.

- ^ a b c d Leonard Maltin's movie and video guide 1993. Penguin Group. 1992. pp. 499, 1166, 1181, 1209. ISBN 978-0-452-26857-9.

- ^ Colangelo, B. J. (February 9, 2022). "Let's Revisit Gremlins 2's Wonderfully Strange Cameos". /Film. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Conner, Floyd (September 1, 2000). Football's Most Wanted™: The Top 10 Book of the Great Game's Outrageous Characters, Fortunate Fumbles, and Other Oddities. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-309-1.

- ^ Marill, Alvin H. (1987). Movies Made For Television: The Telefeature and the Mini-series, 1964–1986. New York: Baseline/New York Zoetrope. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-918432-85-5.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (January 17, 2020). Encyclopedia of Television Pilots. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3810-2.

- ^ Batchelor, Bob; Coombs, Danielle Sarver, eds. (2014). We Are What We Sell: How Advertising Shapes American Life. . . And Always Has. ABC-CLIO. p. 161. ISBN 978-0313392450. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Alfano, Peter (October 9, 1983). "Athletes Advertising Images: Bullies to 'Beefcake'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Dick Butkus Out To Give Echo Greater Exposure". Chicago Tribune. July 11, 1985. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ a b McCallum, Jack (2012). Sports Illustrated Book of the Apocalypse: Two Decades of Sports Absurdity. Diversion Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1938120152. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ "Butkus Joins CBS Team". Logansport Pharos-Tribune. Associated Press. July 19, 1988. p. 10. Retrieved August 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stewart, Larry (March 23, 2001). "Butkus Believes XFL Had Bad Marketing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (September 20, 2005). "Mr. Butkus Goes Back to High School". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ White, Mike (October 10, 2005). "Butkus leaves Montour". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ Telander, Rick (September 6, 1993). "The Last Angry Men". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Where are they now: Dick Butkus". University of Illinois. June 20, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ Bisheff, Steve (December 26, 1993). "Butkus' USC Work Habits Deserve Hall Of Fame Vote". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "Matthew "Matt" Butkus". National Lithuanian American Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Evans, Thayer (March 8, 2016). "Jaguars' Luke Butkus will be new offensive line coach at Illinois". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ "Luke Butkus". packers.com. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "2018 Men's Volleyball Roster". UCLA Bruins. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Butkus, Dick (September 4, 2017). "Dick Butkus: Don't overlook football's benefits". USA Today. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Farrar, Doug (November 20, 2012). "Outside the Game: Long after his retirement, Dick Butkus shows more heart than ever". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Fred (October 5, 2023). "Dick Butkus, legendary Chicago Bears linebacker and Hall of Famer, dies at 80". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ DeArdo, Bryan (November 8, 2023). "Dick Butkus, Bears legend and Hall of Fame linebacker, cause of death at 80 revealed". CBS Sports. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "Fields and Moore lead the Bears to their first win of the season, beating the Commanders 40-20". ESPN. October 5, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Ryan (October 6, 2023). "Bears win after Dick Butkus' death reminiscent of Walter Payton 1999 game". NBC Chicago. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Pompei 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Reyes, Lorenzo (February 28, 2014). "Through 'I Play Clean' campaign, Butkus creates awareness". USA Today. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

Bibliography

- Chicago Tribune staff (2015). The Chicago Tribune Book of the Chicago Bears: A Decade-By-Decade History. Agate Publishing. ISBN 978-1572847583.

- Freedman, Lew (2006). Game of My Life: Chicago Bears. Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 1596701005.

- Pompei, Dan (December 15, 2012). "Bear for all seasons". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

Further reading

- Butkus, Dick (1997). Butkus: Flesh and Blood. Doubleday. ISBN 0385486480.

- Butkus, Dick (1972). Stop-Action. Dutton. ISBN 0525210059.

External links

- Dick Butkus at the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Dick Butkus at the College Football Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from NFL.com · Pro Football Reference

- Dick Butkus at IMDb

- Dick Butkus at the TCM Movie Database

- 1942 births

- 2023 deaths

- All-American college football players

- American football centers

- American football middle linebackers

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American people of Lithuanian descent

- Chicago Bears announcers

- Chicago Bears players

- Chicago Vocational High School alumni

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Deaths from atherosclerosis

- Illinois Fighting Illini football players

- National Conference Pro Bowl players

- National Football League announcers

- National Football League players with retired numbers

- Players of American football from Chicago

- Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees

- United States Football League announcers

- Western Conference Pro Bowl players

- XFL (2001) announcers