Pale of Calais

Pale of Calais | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1347–1558 | |||||||||

| Motto: Veritas Temporis filia "Truth, the daughter of Time" | |||||||||

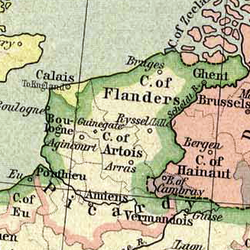

The Pale of Calais (yellow) in 1477. | |||||||||

| Status | Overseas possession of England | ||||||||

| Capital | Calais | ||||||||

| Common languages | English, Dutch, French, Picard | ||||||||

| Religion | Official: Catholic (until 1534); (from 1553) Church of England (1534-1553) Others: Judaism | ||||||||

| Lord | |||||||||

• 1347–1377 | Edward III (first) | ||||||||

• 1553–1558 | Mary I (last) | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1353 | Reynold Cobham (first) | ||||||||

• 1553–1558 | Thomas Wentworth (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages | ||||||||

| 3 August 1347 | |||||||||

| 8 May 1360 | |||||||||

| 8 January 1558 | |||||||||

| 2 May 1598 | |||||||||

| Currency | Sterling | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | France | ||||||||

The Pale of Calais[1] was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558.[2] The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent siege of Calais, and was confirmed at the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, in the reign of Edward III of England. It became an important economic centre for England in Europe's textile trade centred in Flanders.

The Pale, which was historically part of Flanders, also provided England with a permanent strategic, defensible outpost from which it could plan and launch military action on the continent. Its position on the English Channel meant it could be reinforced, garrisoned and supplied over the short distance by sea. The territory was bilingual with English and Flemish commonly spoken.[3][4][5] It was represented in the Parliament of England by the Calais constituency.

During the reign of Mary I of England, the Pale was unexpectedly retaken by the French following a siege in 1558 during their campaigns against the Spanish (whose king was also married to queen Mary) in the County of Flanders. Subsequently, the English textile trade abandoned Calais and moved to the Habsburg Netherlands.

Toponym

The pale is a "jurisdiction, area"[6] (see 'pale', English: Etymology 2.6. on Wiktionary). English "Cales" (now supplanted by French Calais) derives from Caleti, an ancient Celtic people who lived along the coast of the English Channel.[7]

Geography

The actual area of the Pale of Calais is difficult to delineate because boundaries constantly changed and often included ill-defined marsh and waterways. Over those wetlands, the territory was roughly divided in low hills on the west and the lower coastlands to the east.[8] The Pale roughly encompassed the land between Gravelines and Wissant, which was about 20 square miles (52 km2).[9][8] Throughout its history, the French were continually retaking small pieces of the territory, particularly land in the southwest.[8]

The Pale of Calais is roughly within the modern French communes of Andres, Ardres, Balinghem, Bonningues-lès-Calais, Calais, Campagne-lès-Guines, Coquelles, Coulogne, Fréthun, Guemps, Guînes, Les Attaques, Hames-Boucres, Hervelinghen, Marck, Nielles-lès-Calais, Nouvelle-Église, Offekerque, Oye-Plage, Peuplingues, Pihen-lès-Guînes, Sangatte, Saint-Pierre,[10] Saint-Tricat, and Vieille-Église.

History

Calais was a prize of war won in the Battle of Crécy of 1346 by Edward III of England after a long siege. Its capture gave England not only a key stronghold in the world’s textile trade centered in Flanders, but provided a strategic, defensible military outpost for England to regroup in future wars on the continent; the city's position on the English Channel could be reinforced over the short distance by sea. English sovereignty was confirmed under the Treaty of Brétigny, signed on 8 May 1360, when Edward renounced the throne of France in return for substantial lands, namely Aquitaine and the territory around Calais.[11] By 1453, at the end of the Hundred Years' War, the Pale was the last part of mainland France in English hands. It served successfully as a base for English expeditions such as the Siege of Boulogne, launched by Henry VII in 1492.

The short trip across the Strait of Dover afforded convenient garrison and supply by sea. However, the lack of natural inland defences necessitated the construction and maintenance of military fortifications, at some expense. Nevertheless, a critical factor in the stability of English government there over the centuries was the rivalry of France and Burgundy, both of which coveted the strategic position of the city; each left it to the English rather than to concede it to each other. Eventually, political strategies shifted at the division of Burgundian territory in the Low Countries between France and Spain and, when Henry VIII suffered setbacks in the Sieges of Boulogne (1544–1546), the approach to Calais opened to the south. Then in 1550 the Crown, in a crisis of royal succession, withdrew from Boulogne.[8]

The Pale of Calais remained part of England until unexpectedly lost by Mary I to France in 1558. After secret preparations, 30,000 French troops, led by Francis, Duke of Guise, took the city, which quickly capitulated under the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559). In England, blame was attached to the Queen, entrenching Protestant resolve against her. Although the loss of the Pale of Calais was a lesser blow to the English economy than was feared, the retreat of English power was a permanent blot to her reign. Indeed, the chronicler Raphael Holinshead records that a few months later a distraught Mary, lying on her death bed, graphically confided to her family her feelings: “When I am dead and opened, you shall find ‘Calais’ lying in my heart”.[12] Subsequently, the English wool market adjusted and the English textile trade shifted up to the Habsburg Netherlands.[13]

During English governance, the weavers of the Pale maintained their output, which industry was a distinctive mark of Flemish culture.[3] At the same time, the Pale performed as an integral part of England in election of its members to Parliament, and as English citizens the Pale sent and received people to and from various parts of the British Isles.

Artistic interpretations

The hardships endured during the prolonged siege of 1346–47 are the subject of Auguste Rodin's poignant sculpture of 1889, The Burghers of Calais.[14]

See also

- English claims to the French throne

- History of Calais

- List of Captains, Lieutenants and Lords Deputies of English Calais

- The Pale (Ireland)

- Treasurer of Calais

References

- ^ (Middle English, Cales /ˈkæləs/; Template:Lang-vls; Template:Lang-fr)

- ^ Rose, Susan (2008). Calais: An English Town in France, 1347–1558. pp. 107, 156.

- ^ a b Dumitrescu, Theodor (2007). The early Tudor court and international musical relations. England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7546-5542-8.

- ^ Rose, Susan (2008). Calais: An English Town in France, 1347–1558. pp. passim.

- ^ Sandeman, George Amelius Crawshay (October 2009). Calais under English Rule. BiblioBazaar. pp. 48, 61, 81. ISBN 9781115448154.

- ^ "Pale (noun)". The New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd ed.). 2013.

See also: The English Pale in Ireland. - ^ Harper, Douglas. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d Sandeman, George Amelius Crawshay (October 2009). Calais under English Rule. BiblioBazaar. p. 114. ISBN 9781115448154.

- ^ Darian-Smith, Eve (1999). Bridging divides: the Channel Tunnel and English legal identity in the new Europe. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-21610-5.

- ^ Calais absorbed Saint-Pierre-lès-Calais inhabited with 33290 inhabitants in 1885, now southern part of Calais

- ^ Fisher, H.A.L. (1936). A History of Europe. Great Britain: Edward Arnold & Co. p. 322.

- ^ Bentley, James (1991). The Gateway to France. London: Viking. p. 10. ISBN 0670832065. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Jocelyn (1999). The Renaissance. New York: Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 0-203-98177-4.

- ^ Linduff, David G. Wilkins, Bernard Schultz, Katheryn M. (1994). Art past, art present (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 454. ISBN 0-13-062084-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pale of Calais

- 1347 establishments in Europe

- 1558 disestablishments in Europe

- 14th century in England

- 14th century in France

- 15th century in England

- 15th century in France

- 16th century in England

- 16th century in France

- Former exclaves

- Geographical, historical and cultural regions of France

- Geography of the Pas-de-Calais

- History of Calais

- Hundred Years' War