Dallas Grand Prix

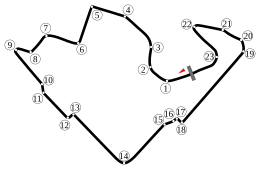

| Fair Park, 1984 | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 8 |

| First held | 1984 |

| Last held | 1996 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | Chevrolet (2) Ford (2) Oldsmobile (2) |

| Circuit length | 2.1 km (1.3 miles) |

| Race length | 161.7 km (100.4 miles) |

| Laps | 77 |

| Last race (1996) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

The Dallas Grand Prix was a round of the Formula One World Championship held in Dallas in 1984. The race was cancelled in 1985 due to financial problems, safety concerns, and citizen complaints stemming from the temporary street circuit's close proximity to residential neighborhoods. In 1988, the race was revived as a round of the Trans-Am Series. In 1989, the event moved to the northern Dallas suburb of Addison. After a one-year hiatus in 1992, the event returned to Dallas at a new street circuit around Reunion Arena, and was last held in 1996.

Formula 1

The 1984 Dallas Grand Prix was conceived as a way to demonstrate Dallas's status as a "world-class city".[1][2] The Formula One (F1) race took place on July 8, 1984 on a temporary street circuit in Fair Park, despite pre-race organizational problems, intense 100 °F (38 °C) heat, and poor track conditions including pavement failures. Of the 26 cars that started the race, only eight finished, and the race is perhaps best known for driver Nigel Mansell collapsing from exhaustion while trying to push his broken car to the finish line. In a 2022 statement to D Magazine, co-organizer Larry Waldrop said that the July date was chosen to minimize the possibility of rain during the event, and he expressed regret that the organizers did not adequately anticipate the effects of Texas summer heat on the event generally and the pavement specifically.[2]

Financial problems and safety concerns contributed to the 1985 race being cancelled.[3] Race organizer Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc., founded by Waldrop, Don Walker, and Buddy Boren, had executed a contract with the Formula One Constructors' Association (FOCA) to hold five races in Dallas.[2] Walker, a local real estate investor, bought out Boren's share in late 1983 and sidelined Waldrop. Walker clashed with co-organizers and officials and spent money prodigiously. Walker could not agree with FOCA or Dallas officials on a 1985 race date, and the company would not pay the front money for the race. Around this time, Walker suddenly withdrew from Can-Am racing citing financial reasons, was forced off the corporate boards of two banks over alleged financial irregularities, and began selling his large collection of exotic sports cars. Both Walker and Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc. ended up in financial distress and were soon under investigation by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and Securities and Exchange Commission over allegations that Walker had illegally siphoned money from the company and various real estate ventures to fund his lavish lifestyle.[4] Waldrop negotiated with FOCA leader Bernie Ecclestone in late 1984 in an attempt to bypass Walker and revive the event, but the effort came to naught.[2] Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc. entered bankruptcy in March 1985, ending any possibility that a follow-on F1 race would take place at Fair Park.[2][4]

Another major factor in the cancellation of future F1 races was pushback from residents of the nearby, populous Fair Park neighborhood,[2] which was majority Black and low-income.[5] Although the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce said the event would benefit some local Black-owned businesses, the organization and Dallas city councilwoman Diane Ragsdale said they had been excluded from the planning process, and Ragsdale told The New York Times that the failure to consult with neighbors and take noise concerns seriously were part of a historic pattern of "total disrespect for the neighborhood."[5] In 1984, Ragsdale and the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuit against Walker and Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc.; in 2022, Waldrop said that it was the main hurdle in his late 1984 FOCA negotiations, because he could not guarantee that authorities would allow the 1985 race to take place.[2]

Trans-Am era

Boren was eventually able to organize a 1988 Trans-Am Series race at Fair Park after reaching an agreement with Ragsdale and the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce to donate a substantial portion of the race receipts to charity.[6]

Continued complaints about noise and inconvenience from nearby Fair Park homeowners led organizers to seek a less noise-sensitive venue. They decided on Addison Airport, located in a largely industrial area in the nearby town of Addison. The 1989 event was held on May 12–14 on a new temporary 2.53 km (1.57 mi) circuit built partially on public streets and partially on taxiways and the south end of the runway. Although it benefited Addison hotels and restaurants, the race disrupted operations at the busy airfield for weeks, prompting airport businesses and the airport management company to lodge complaints with the town and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in 1990. After the 1991 race, the FAA, the town, the race organizers, and airport managers and tenants agreed that 1992 would be the last year the race would be held at the airport. The agreement became moot when the race organizers, who had lost money on the previous events, cancelled the 1992 race citing financial reasons.[7]

In 1993, the race relocated to a temporary street circuit around the Reunion Arena, at the time home to many of Dallas's sports teams.

Winners

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Year | Driver | Constructor | Location | Class | Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Williams-Honda | Fair Park | Formula One | Report | |

| 1985 – 1987 |

Not held | ||||

| 1988 | Audi | Fair Park | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1989 | Ford | Addison Airport | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1990 | Oldsmobile | Addison Airport | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1991 | Oldsmobile | Addison Airport | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1992 | Not held | ||||

| 1993 | Chevrolet | Reunion Arena | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1994 | Ford | Reunion Arena | Trans-Am | Report | |

| 1995 | Not held | ||||

| 1996 | Chevrolet | Reunion Arena | Trans-Am | Report | |

| Sources:[8][9] | |||||

References

- ^ Lang, Mike (1992). Grand Prix!: Race-by-race account of Formula 1 World Championship motor racing. Volume 4: 1981 to 1984. Haynes Publishing Group. pp. 259–264. ISBN 0-85429-733-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Arnold, Jon (October 21, 2022). "Remembering the 1984 Dallas Grand Prix, Formula 1's Disastrous Trip to North Texas". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ David Hayhoe, Formula 1: The Knowledge – 2nd Edition, 2021, page 35.

- ^ a b Arnold, Jon (July 1, 1985). "Grand Prix, Grand Scam, Grand Jury?". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Applebome, Peter (July 8, 1984). "Dallas Seeks Glamour in Grand Prix". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

It shows a total disrespect for the neighborhood, said a black Dallas City Councilwoman, Diane Ragsdale. It's an age-old problem here.

- ^ Lumpkin, Rhae (April 1, 1988). "Grand Prix '88". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Bleakley, Bruce (2017). Addison Airport: Serving Business Aviation for 60 Years, 1957–2017. Dallas, Texas: Brown Books Publishing Group. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-61254-839-5.

- ^ Higham, Peter (1995). "Fair Park". The Guinness Guide to International Motor Racing. London, England: Motorbooks International. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-7603-0152-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "SCCA Pro Racing Archives". Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2008.