Enceladus Orbilander

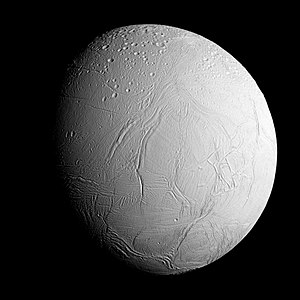

Artist's impression of the Enceladus Orbilander | |

| Mission type | Enceladus Orbiter and Lander |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Website | https://space.jhuapl.edu/projects-and-studies/enceladus-orbilander |

| Mission duration |

|

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | APL (proposed) |

| Launch mass | 6610 kg [1]: 18 |

| Dry mass | 2690 kg |

| Power | 741 W (at launch) 589 W (landing) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | October 2038 (proposed) [1]: 33 |

| Rocket | Space Launch System Block 2 (proposed) |

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center, Pad 39B |

| Contractor | NASA |

| Flyby of Jupiter | |

| Closest approach | October 2040 (proposed) |

| Distance | 4,730,000 km (2,940,000 mi) |

| Saturn orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | August 2045 (proposed) |

| Orbital departure | early 2050 (proposed) |

| Enceladus orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | early 2050 (proposed) |

| Orbital departure | mid 2051 (proposed) |

| Enceladus lander | |

| Landing date | mid 2051 (proposed) |

Large Strategic Science Missions Planetary Science Division | |

The Enceladus Orbilander is a proposed NASA Flagship mission to Saturn's moon Enceladus. The Enceladus Orbilander would spend a year and a half orbiting Enceladus and sampling its water plumes, which stretch into space, before landing on the surface for a two-year mission to study materials for evidence of life.[1] The mission, with an estimated cost of $4.9 billion, could launch in the late 2030s on a Space Launch System or Falcon Heavy with a landing in the early 2050s. It was proposed in the 2023–2032 Planetary Science Decadal Survey as the third highest priority Flagship mission, after the Uranus Orbiter and Probe and the Mars Sample Return program.[2]

Background

At 500 kilometres (310 miles) in diameter, Enceladus is the sixth largest moon of Saturn and the 19th largest in the solar system.[3] Enceladus has been visited and imaged in detail by three other probes: the twin Voyager spacecraft, and the Saturn orbiting Cassini spacecraft. Out of these, Cassini investigated Enceladus in the most detail and contributed the most to the current scientific understanding of Enceladus. Cassini's 23 targeted closed flybys,[4] helped discover that not only was Enceladus' terrain was youthful and geologically active world, but that the moon possessed a subsurface ocean and active water plumes.[5]. Cassini also provided evidence of hydrothermal processes driving both the geysers and Enceladus' active geology, making the moon one of the most attractive places to find life within the solar system.

After Cassini's mission, a variety of proposals to follow-up on Cassini's findings at Enceladus.[6] Journey to Enceladus and Titan, an astrobiology mission to Enceladus and Titan, competed for the 13th Discovery Program mission but was not selected.[7][8] Later, In 2017, two Enceladus focused astrobiology missions, Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability and Enceladus Life Finder competed for the 4th New Frontiers mission, but were ultimately not selected.[9][10]

The Enceladus Orbilander proposal was created by a team led by Shannon MacKenzie to support the Planetary Science Decadal Survey.[11] While previous mission studies had investigated multiple flybys to study Enceladus, MacKenzie's team, studying a Flagship mission architecture with a greater budget cap, decided to study an orbiter, lander, or a combination thereof.[12] Ultimately, the decision to combine the orbiter and lander into one spacecraft was informed by Enceladus' small size and negligible gravity, which results in trivial delta-v to land.[13] In the 2022-2032 Planetary Decadal Survey, the Enceladus Orbilander was recommended as the third highest priority new flagship mission.[14] The selection was motivated by proposal's exobiology and planetary habitability focus.[15]

Spacecraft Design

Due to Enceladus's small size, the amount of energy required to land compared to capturing into orbit is negligible. Therefore, the Enceladus Orbilander is envisioned uniquely combine both the functions of an orbiter and a lander into a single spacecraft.[16]

Scientific instruments

The proposed spacecraft will carry three separate instrument suites and a sampling system. Each instrument suite is tailored towards a different regime of science operations.

The proposed instruments are: [1]: 10,B7-B10

| Instrument | Heritage Instrument (Mission) | Science Suite |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) | MASPEX (Europa Clipper) | Life Detection Suite |

| Separation Mass Spectrometer (SMS) | Sample Analysis at Mars (Curiosity) | Life Detection Suite |

| Electrochemical Sensor Array (ESA) | Wet Chemistry Laboratory (Phoenix) | Life Detection Suite |

| Microcapillary Electrophoresis-Laser Induced Fluorescence | N/A | Life Detection Suite |

| Microscope | MECA Atomic Force Microscope (Phoenix) | Life Detection Suite |

| Solid State Nanopore Sequencer | N/A | Life Detection Suite |

| Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) | Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (New Horizons) | Remote Sensing and Reconnaissance Detection Suite |

| Wide Angle Camera (WAC) | ECAM-M50 (Janus) | Remote Sensing and Reconnaissance Detection Suite |

| Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) | Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (BepiColombo) | Remote Sensing and Reconnaissance Detection Suite |

| Context Imager | Stereo Surface Imager (Phoenix) | In Situ Suite |

| Seismometer | Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (Insight) | In Situ Suite |

Additionally, three separate sampling systems are proposed for each stage of flight: a 1 square meter funnel to passively collect particles, a scoop for active particle collection on the surface, and a gas inlet for gas emissions.[1]: 10,B11

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Astrobiology

- Enceladus Explorer

- Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability (ELSAH)

- Explorer of Enceladus and Titan (E2T)

- Europa Clipper

- Journey to Enceladus and Titan (JET)

- Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE)

- THEO

References

- ^ a b c d e f MacKenzie, Shannon M.; Kirby, Karen W.; Greenauer, Peter J.; Neveu, Marc; Gold, Rob; Davila, Alfonso; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Cable, Morgan; Craft, Kate; Eigenbrode, Jennifer; Glein, Christopher; Hofgartner, Jason; Mckay, Christopher; Phillips-Lander, Charity; Waite, Hunter; Burton, Dana; Seifert, Helmut; Boye, Jeff; Brock, Spencer; Chen, Michelle; Coker, Rob; Colonel, Grace; Criss, Tom; Crowley, Doug (14 October 2020). "Encealdus Orbilander: A Flagship Mission Concept for Astrobiology". NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (19 April 2022). "Planetary science decadal endorses Mars sample return, outer planets missions". SpaceNews. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Enceladus: Facts & Figures". Solar System Exploration. NASA. 12 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ Cofield, Calla (26 October 2017). "How Cassini Mission's Twists and Turns Led to Discovery of Enceladus' Plumes". Space.com. Future US Inc. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Cassini at Enceladus: A Decade-Plus of Discovery - NASA Science". NASA. 24 January 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Carter, Jamie (10 June 2022). "Seven Things You Need To Know About NASA's New $4.9 Billion Mission To Enceladus, A Tiny Moon Of Saturn". Forbes. Forbes. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Sotin, C.; Altwegg, K.; Brown, R.H.; et al. (2011). JET: Journey to Enceladus and Titan (PDF). 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne. "NASA Selects Two Missions to Explore the Early Solar System - NASA". nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (15 September 2017). "Back to Saturn? Five Missions Proposed to Follow Cassini". The New York Times.

- ^ Inner Workings: Icy ocean worlds offer chances to find life. Adam Mann, PNAS, 2 May 2017, vol. 114 no. 18 4566–4568, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703361114

- ^ Bartels, Meghan = (5 October 2020). "If we want to find life on Saturn's moon Enceladus, we need to rule out Earthly hitchhikers". Space.com. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ MacKenzie, Shannon M.; Neveu, Marc; Davila, Alfonso F.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Craft, Kathleen L.; Cable, Morgan L.; Phillips-Lander, Charity M.; Hofgartner, Jason D.; Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; Waite, J. Hunter; Glein, Christopher R.; Gold, Robert; Greenauer, Peter J.; Kirby, Karen; Bradburne, Christopher; Kounaves, Samuel P.; Malaska, Michael J.; Postberg, Frank; Patterson, G. Wesley; Porco, Carolyn; Núñez, Jorge I.; German, Chris; Huber, Julie A.; McKay, Christopher P.; Vera, Jean-Pierre de; Brucato, John Robert; Spilker, Linda J. (27 April 2021). "The Enceladus Orbilander Mission Concept: Balancing Return and Resources in the Search for Life". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (2): 77. doi:10.3847/PSJ/abe4da. ISSN 2632-3338. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Strauss, Mark (19 June 2023). "Diamond in the Dark". Air & Space Quarterly. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Blatt, Josh. "Report Identifies Priority Planetary Science Missions, Planetary Defense Efforts, and Strategic Investments for the Next Decade". www.nationalacademies.org. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032". National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 23 October 2023. doi:10.17226/26522. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy. "Meet Orbilander, a Mission to Search for Life on Enceladus". The Planetary Society. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 26 April 2024.