Étienne-Jules Marey

Étienne-Jules Marey (French: [etjɛn ʒyl maʁɛ]; 5 March 1830, Beaune, Côte-d'Or – 15 May 1904,[1] Paris) was a French scientist, physiologist and chronophotographer.

His work was significant in the development of cardiology, physical instrumentation, aviation, cinematography and the science of laboratory photography. He is widely considered to be a pioneer of photography and an influential pioneer of the history of cinema. He was also a pioneer in establishing a variety of graphical techniques for the display and interpretation of quantitative data from physiological measurement.[2]

Biography

[edit]

Marey started by studying blood circulation in the human body. Then he shifted to analyzing heart beats, respiration, muscles (myography), and movement of the body. To aid his studies he developed many instruments for precise measurements. For example, in 1859, in collaboration with the physiologist Auguste Chauveau and the watch manufacturer Breguet, he developed a wearable Sphygmograph to measure the pulse. This sphygmograph was an improvement on an earlier and more cumbersome design by the German physiologist Karl von Vierordt.[3] In 1869 Marey constructed a very delicate artificial insect to show how an insect flies and to demonstrate the figure-8 shape it produced during movement of its wings. He fixed a gold foil to an insect wing and shone light on it to study the flapping of the wing. He also used a soot covered glass-fibre introduced along the path of the insect wing to determine if it crossed with the wing in the upper stroke or lower stroke by examining the side on which the soot was cleared.[4] Then he became fascinated by movements of air and started to study bigger flying animals, like birds. He adopted and further developed animated photography into a separate field of chronophotography in the 1880s. His revolutionary idea was to record several phases of movement on one photographic surface. In 1890 he published a substantial volume entitled Le Vol des Oiseaux (The Flight of Birds), richly illustrated with photographs, drawings, and diagrams. He also created stunningly precise sculptures of various flying birds.

Marey studied other animals too. He published La Machine animale in 1873 (translated as "Animal Mechanism"). The English photographer Eadweard Muybridge carried out his "Photographic Investigation" in Palo Alto, California, to prove [dubious – discuss] that Marey was right when he wrote that a galloping horse for a brief moment had all four hooves off the ground. Muybridge published his photos in 1879 and received some public attention.

Marey hoped to merge anatomy and physiology. To better understand his chronophotographic images, he compared them with images of the anatomy, skeleton, joints, and muscles of the same species. Marey produced a series of drawings showing a horse trotting and galloping, first in the flesh and then as a skeleton.

The presence and activity of Marey in Naples is well documented,[5] in particular thanks to the documentation preserved in the historical archive of the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. Marey began to travel to Naples presumably because of his relation with madame Vilbort, wife of Joseph Vilbort, the director of the French journal Le Globe. Madame Vilbort moved to Naples to cure her illness, thanks to the warm climate, and Marey followed her. Marey and madame Vilbort bought villa Maria in Posillipo in 1880. Marey accomplished in Naples part of his studies aimed at the realization of his pre-cinematographic tools and in the Dohrn zoological station studied the movement of fishes hosted in the aquarium's tanks. In a letter dated 1 November 1876 Marey requested the Stazione Zoologica to provide live ray fishes for his studies. Among the documentation that witnesses the collaboration of Marey with Anton Dohrn is the archive at the zoological station which preserves photos where the two appear together during an excursion and show Marey on board Dohrn's boat. The usage of the chronophotographic gun, which Marey used to aim at birds, but without shooting, appeared unusual to local people who referred to Marey sometimes as the "silly from Posillipo" ("lo scemo di Posillipo").[6]

He proposed "Marey's Law", a law that stated that an increase in blood pressure caused a lowering of the heart rate and vice versa.[7]

He also invented "Marey's tambour" for physiological experiments.[8]

Chronophotography

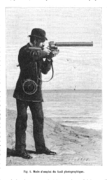

[edit]Marey's chronophotographic gun was first made in 1882.[9] This instrument was capable of taking 12 consecutive frames a second, with all the frames recorded on the same picture. Using these pictures he studied horses, birds, dogs, sheep, donkeys, elephants, fish, microscopic creatures, molluscs, insects, reptiles, etc. Some call it Marey's "animated zoo". Marey also conducted the famous study about cats always landing on their feet. He conducted very similar studies with a chicken and a dog and found that they could do almost the same. Marey also studied human locomotion. He published another book Le Mouvement in 1894.

-

Étienne-Jules Marey in Napoli. In the hand notes the date is readable: "March 1882"

-

Illustration of the chronophotographic gun from La Nature n. 464, 22 April 1882, p. 326

-

Marey's photographic gun, on display at Conservatoire national des arts et métiers.

In 1885 Marey mentioned how he could playback the animation from his gun using the phenakistiscope.[10] In 1889 he developed the chronophotographe camera which took images on film at even spacing. He however did not manage to play it back as he was unable to move between the frames in an even manner. Edison visited Marey in 1889 and was able to solve the problem using a sprocketed film advance mechanism along with W.L. Dickison who was developing something using the cylindrical model of the phonograph.[11]

Towards the end of his life he returned to studying the movement of quite abstract forms, like a falling ball. His last great work was the observation and photography of smoke trails. This research was partially funded by Samuel Pierpont Langley under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution, after the two met in Paris at the Exposition Universelle (1900). In 1901 he was able to build a smoke machine with 58 smoke trails. It became one of the first aerodynamic wind tunnels.

Bibliography

[edit]

- Physiologie médicale de la circulation du sang (1863) (Physiology of blood circulation.)

- Études physiologiques sur les caractères graphiques des battements du cœur (1865) (Physiological studies on the graphic characteristics of heartbeats.)

- Du mouvement dans les fonctions de la vie (Movement in the functions of life.)

- Experiments done in his private laboratory – La Revue scientifique (1866)

- Experiments done at Collège de France – Germer-Baillière (1868)

- Du vol des oiseaux (The flight of birds), La Revue scientifique 14, 21 August 11 September and 2 October 1869 (Text on line)

- La Machine animale. Locomotion terrestre et aérienne (The animal machine, terrestrial and aerial locomotion)(1873–1874)

- Physiologie expérimentale (Experimental physiology) (1875)

- Pression et vitesse du sang (Pressure and flow-rate of blood) (1876)

- Moteurs Animés. Expériences de physiologie graphique, (A Study in Motion) La Nature, N°278 – 28 September 1878 et N°279 – 5 October 1878

- La Méthode graphique dans les sciences expérimentales (1878) (Text on line)

- La Circulation du sang à l'état physiologique et dans les maladies (1881) (Text on line)

- Études pratiques sur la marche de l'homme. Expériences faites à la station physiologique du Parc des Princes., La Nature, N° 608 – 24 January 1885

- Le vol des oiseaux (1890) éd. G. Masson – Préface, La Revue scientifique, 19 October 1889

- Des appareils enregistreurs de la vitesse, La Nature, N°878 – 29 March 1890 (Text on line)

- Le vol des insectes étudié par la chronophotographie. La Nature N°974 – 30 Janvier 1892 Text on line

- Mouvements de natation de la raie, La Nature, N°1029 – 18 February 1893 (Text en line)

- Le Mouvement Des Liquides Étudié Par La Chronophotographie La Nature, N°1040 – 6 mai 1893 (Text en line)

- avec Georges Demenÿ, Études de physiologie artistique faites au moyen de la chronophotographie (1893)

- Des mouvements que certains animaux exécutent pour retomber sur leurs pieds, lorsqu'ils sont précipités d'un lieu élevé, La Nature, N°1119 – 10 November 1894 (Text en line)

- Le Mouvement (1894)

- La Station physiologique de Paris, La Revue scientifique, 29 December 1894 (Text en line) et 6 January 1895 (Text en line)

- Analyse des mouvements du cheval par la chronophotographie, La Nature, N°1306 – 11 Juin 1898 Text en line

See also

[edit]- Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904)

- Chronophotography

- Velocimetry

References

[edit]- ^ "Bulletin de décès".

- ^ Smith, Laurence D.; Best, Lisa A.; Cylke, Virginia A.; Stubbs, D. Alan (2000). "Psychology without p values: Data analysis at the turn of the 19th Century". American Psychologist. 55 (2): 260–263. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.260. PMID 10717979.

- ^ Braun, Marta, 1992, Picturing Time: The Work of Etienne-Jules Marey, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ^ Braun, Marta (1994). Picturing Time: The Work of Etienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904). University of Chicago Press. pp. 31–34.

- ^ (IT) Étienne-Jules Marey nell’Archivio Storico della Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli

- ^ (IT) Laurent Mannoni, La grande arte della luce e dell'ombra. Archeologia del cinema, Lindau 1994–2007, ISBN 978-88-71-80-684-6, (IT) Virgilio Tosi Il cinema prima del cinema, Il castoro, 2007, ISBN 978-88-80-33-393-7

- ^ Prescott, Sara L.; Liberles, Stephen D. (16 February 2022). "Internal senses of the vagus nerve". Neuron. 110 (4): 579–599. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.020. ISSN 0896-6273. PMC 8857038. PMID 35051375.

- ^ Putnam, James J. (September 1879). "On the Reliability of Marey's Tambour in Experiments requiring Accurate Notations of Time". The Journal of Physiology. 2 (3): 209–213. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1879.sp000059. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 1484634. PMID 16991287.

- ^ Rossell, Deac (2013). "Chronophotography in the context of moving pictures". Early Popular Visual Culture. 11 (1): 10–27. doi:10.1080/17460654.2012.756651. ISSN 1746-0654.

- ^ Tortajada, Maria (31 December 2014), Albera, François; Tortajada, Maria (eds.), "Marey And The Synthesis Of Movement: The Reconstruction of a Concept", Cine-Dispositives, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 93–114, doi:10.1515/9789048523443-007, ISBN 978-90-485-2344-3, retrieved 24 July 2024

- ^ Haddleton, Graham P. (2003). "Etienne-Jules Marey: a short biography and appreciation". In Cavailler, Claude; Haddleton, Graham P.; Hugenschmidt, Manfred (eds.). 25th International Congress on High-Speed Photography and Photonics. p. 188. doi:10.1117/12.516735.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Étienne-Jules Marey at the Internet Archive

- Works by Étienne-Jules Marey at Open Library

- The science of movement and the image of time: online exhibition by the BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris), with the Collège de France and Pr Marta Braun (Ryerson University), author of Picturing Time : The Work of Etienne-Jules Marey (University of Chicago Press, 1992)

- Movements of Air, Etienne-Jules Marey, Photographer of Fluids

- Online exhibition of images, and movies, and animation

- Etienne-Jules Marey: digital library, BIUM (Paris)

- Photo, bibliography, and biography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Étienne-Jules Marey at IMDb

- La machine animale

- "Bodies Against Time," an essay by Zoe Beloff in online magazine Triple Canopy.

- Archival Materials on the European Film Gateway Portal

- Le Vol des Oiseaux

- 1830 births

- 1904 deaths

- 19th-century French photographers

- People from Beaune

- Pioneers of photography

- French physiologists

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Academic staff of the Collège de France

- 19th-century French scientists

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala