List of battleships of France

Between 1889 and 1949, the French Navy built a series of pre-dreadnought, dreadnought, and fast battleships, ultimately totaling thirty-four vessels: twenty-three pre-dreadnoughts, seven dreadnoughts, and four fast battleships. Another seven—five dreadnoughts and two fast battleships—were cancelled in various stages of construction (one of which was converted into an aircraft carrier while being built) and seven more were cancelled before work began. The first battleship construction program followed a period of confusion in strategic thinking in France over the optimal shape of the fleet. At the time, the French naval command consisted of competing factions, with one that favored building fleets of capital ships, continuing the program of traditional ironclad warships that had dominated the fleet in the 1860s and 1870s. The other major faction preferred the Jeune École doctrine, which emphasized the use of cheap torpedo boats to destroy expensive capital ships. During the period, naval construction decisions often depended on the Minister of the Navy in office at the time.

A pair of ironclad battleships were cancelled by Admiral Théophile Aube, an adherent of the Jeune École, but one of the two was redesigned as the pre-dreadnought Brennus following Aube's departure. By the end of the decade, the British Naval Defence Act of 1889 that considerably strengthened the Royal Navy provided the justification the battleship faction needed to embark on a similar naval expansion program. The French replied with the Statut Naval (Naval Law) of 1890 that projected a total force of twenty-eight battleships. The initial program ordered four ships, with a fifth added during the design process: Charles Martel, Carnot, Jauréguiberry, Masséna, and Bouvet. These were experimental ships, built to different designs but all to the same broad specifications; they were all characterized by pronounced tumblehome and a lozenge arrangement of a mixed-caliber main battery. All five proved to be disappointments, owing to poor stability and poor resistance to underwater attacks.

The navy then began a series of standardized ships designed by a single architect; these were the three Charlemagne class and the derivatives Iéna and Suffren. The initial series of French battleships saw relatively little activity, being primarily occupied with training activities through the 1890s and 1900s. They alternated between the Northern and Mediterranean Squadrons before being withdrawn from front-line service at the end of the first decade of the 20th century as more modern battleships entered service. In 1900, the French government passed a new Statut Naval to counter growing German naval strength, which resulted in the two République- and four Liberté-class battleships; they were very similar but differed in their secondary battery. These vessels proved to be much more successful than the earlier battleships of the French fleet, and they formed the backbone of the Mediterranean Squadron when war came in 1914.

A new Statut Naval in 1906 brought about the construction of the six Danton-class battleships and the seven dreadnoughts of the Courbet and Bretagne classes. The Dantons were pre-dreadnought vessels built after the launch of the British "all-big-gun" HMS Dreadnought rendered such vessels obsolescent, though the French at that time preferred the higher rate of fire of the lighter secondary guns. Convinced of the need to follow suit with dreadnoughts of their own, the French ordered the four Courbets in 1910 followed by three Bretagnes in 1912. These would be the last battleships completed for two decades, as World War I forced the French to cancel the Normandie and Lyon classes (ordered for the 1913 and 1915 programs) as industrial and financial resources were diverted to the French Army and financial limitations after the war prevented further construction. During the war, the bulk of the French fleet was occupied with guarding the southern end of the Adriatic Sea to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy, while older vessels were used elsewhere, particularly during the Dardanelles campaign, where Bouvet was sunk in 1915. After the war, the surviving pre-dreadnoughts were either scrapped or reduced to secondary roles.

By the mid-1930s, the French again embarked on a naval construction program to counter the German and Italian fleets, resulting in the two Dunkerque-class battleships and fourRichelieu-class battleships; of the four Richelieus that were planned, two were cancelled by the start of World War II, and only one was completed in time to see action during the war. A final design, the Alsace class, was authorized in 1940 after the war began but were cancelled following France's defeat in the Battle of France. The two Dunkerques saw limited action during the war, with Dunkerque being sunk during the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir to prevent her from being seized by the Germans. Bretagne and Provence were also sunk there, and the third member of the class, Lorraine, was seized by the British and turned over to the Free French Naval Forces. Refloated and returned to Toulon, Dunkerque and Provence were later scuttled there with the former's sister ship Strasbourg when the French intentionally scuttled the fleet to prevent German soldiers from capturing the vessels. Richelieu meanwhile was overhauled in the United States and served with the Free French from 1943. Jean Bart, with only one main battery gun turret operational, briefly engaged United States forces during Operation Torch in November 1942, and was eventually completed in the late 1940s. Both she and Richelieu served as training ships before eventually being decommissioned in 1968.

| Armament | The number and type of the primary armament |

|---|---|

| Armor | The maximum thickness of the armored belt |

| Displacement | Ship displacement at full combat load |

| Propulsion | Number of shafts, type of propulsion system, and top speed generated |

| Service | The dates work began and finished on the ship and its ultimate fate |

| Laid down | The date the keel assembly commenced |

| Commissioned | The date the ship was commissioned |

Pre-dreadnought battleships

[edit]Brennus

[edit]

Brennus, built in the late 19th century, was the first pre-dreadnought battleship of the French Navy. During this period, the French Navy experimented with the Jeune École, which emphasized cheap torpedo boats and cruisers instead of the expensive ironclad warships that had dominated naval construction in the 1860s and 1870s, and so the navy ordered a series of experimental designs to determine the most effective ship types. Admiral Théophile Aube, then the Minister of the Navy and a proponent of the Jeune École, cancelled a pair of ironclad battleships in 1886, but after Aube left office his successor allowed one of the vessels to be redesigned as a modern pre-dreadnought battleship. Brennus was the only vessel built to her design, which had been prepared by Charles Ernest Huin, though it provided the basis for several subsequent ships. She departed from earlier French ironclad battleship designs by introducing a number of innovations. These included a main battery of heavy guns mounted on the centerline, homogeneous steel armor, and the first use of Belleville boilers.[1][2]

Brennus spent the majority of her career in the Mediterranean Squadron, initially serving as its flagship. In 1900, she accidentally rammed and sank the destroyer Framée. As newer battleships were commissioned into the fleet, Brennus was relegated to the Reserve Squadron in the early 1900s; she spent this period largely inactive with a reduced crew, being reactivated for training exercises with the rest of the fleet. She was used as a training ship from 1908 to 1914. By the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, her old age and poor condition prevented her from seeing action and she was instead reduced to a hulk. She was ultimately stricken from the naval register in 1919 and sold for scrap three years later.[3][4]

| Ship | Armament[5] | Armor[6] | Displacement[6] | Propulsion[7] | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down[8] | In service[9] | Fate[4] | |||||

| Brennus | 3 × Canon de 340 mm (13.4 in) Modèle 1887 guns | 400 mm (15.7 in) | 11,370 metric tons (11,190 long tons) | 2 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17 kn (31 km/h; 20 mph) | 2 January 1889 | 11 January 1896 | Broken up, 1922 |

Charles Martel

[edit]

Charles Martel was the first of a group of five broadly similar battleships ordered during the 1890 construction program as part of the French response to a major British naval construction program. The five ships were built to the same basic design parameters, though the individual architects were allowed to deviate from each other in lesser details. The ships were ordered in response to the British Naval Defence Act of 1889, which had authorized the construction of the eight Royal Sovereign-class battleships; the French law aimed to keep the fleet in a position of relative parity with the Royal Navy. A total of twenty-eight battleships were to be built throughout the program. To keep costs down and minimize objections from the Chamber of Deputies, the displacement of the new ships would be limited to 12,000 t (12,000 long tons).[10] The basic design for the first ship, Charles Martel, was also prepared by Huin, who based it on Brennus, though the armament was arranged in the lozenge layout that had been used on a number of older ironclad battleships like the Magenta class.[11] The ship proved to be a disappointment in service, as did her four half-sisters, all of which suffered from poor stability, largely a result of their pronounced tumblehome and overloaded construction.[12]

The ship spent her career with the Mediterranean Squadron. In 1897, she joined the International Squadron sent to intervene in the 1897–1898 Greek uprising on Crete against rule by the Ottoman Empire.[13] Charles Martel served as the flagship of the 2nd Division of the Mediterranean Squadron beginning in 1900 before being transferred to the Reserve Squadron in 1902. There, she served as the flagship until she was replaced in 1903. Charles Martel was assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron in 1910 and was then moved to the newly created 3rd Battle Squadron the next year. She returned to reserve status in 1912 and saw no further activity, ultimately being scrapped in 1922.[14][15]

| Ship | Armament[15] | Armor[16] | Displacement[17] | Propulsion[18] | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down[16] | Commissioned[16] | Fate[15] | |||||

| Charles Martel | 2 × Canon de 305 mm (12 in) Modèle 1887 guns 2 × Canon de 274 mm (10.8 in) Modèle 1887 guns |

460 mm | 11,880 t (11,692 long tons) | 2 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17 kn (31 km/h; 20 mph) | 1 August 1891 | June 1897 | Broken up, 1922 |

Carnot

[edit]

Carnot was ordered under the same program that produced Charles Martel, and like the other vessel, she was largely based on Brennus and Magenta. But rather than simply repeat the same design, the French Naval Staff decided to allow different naval architects to build several different designs to evaluate the competing proposals for future programs. Carnot was designed by Victor Saglio, the Under-director of Naval Construction in Toulon. Compared to Charles Martel, Carnot was broadly similar, with the same main battery, though she had a smaller superstructure in an attempt to minimize topweight and thus instability that plagued many French capital ships during this period. The ship was nevertheless still too top-heavy and proved to suffer from insufficient stability. Modifications were made to the ship after she was completed, but they did not solve the problem, and like the rest of the ships of the 1890 program, Carnot was not a particularly successful vessel.[19]

The ship's early career followed a similar trajectory to Charles Martel's; she spent much of it in the Mediterranean Squadron, and she too served with the International Squadron in 1897.[13] She thereafter began alternating stints in the Northern and Mediterranean Squadrons; she was with the Northern Squadron in 1901,[20] followed by a brief return to the Mediterranean as part of the Reserve Squadron in 1903.[21] The year 1904 saw her back with the Northern Squadron,[22] where she remained until 1907, when she was assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron in the Mediterranean.[23] In early 1911, the unit was moved to Brest, France, before returning to Toulon later that year, where it was renumbered as the 3rd Squadron. Carnot was reduced to reserve in 1913 and was ultimately broken up in 1922.[24][25]

| Ship | Armament[26] | Armor[16] | Displacement[27] | Propulsion[27] | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down[28] | Commissioned[28] | Fate[25] | |||||

| Carnot | 2 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1887 guns 2 × Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1887 guns |

460 mm | 11,954 t (11,765 long tons) | 2 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17.8 kn (32.97 km/h; 20.48 mph) | July 1891 | July 1897 | Broken up, 1922 |

Jauréguiberry

[edit]

Jauréguiberry was designed by Amable Lagane, the naval architect who had overseen the construction of one of the Magneta-class ironclads, and as a result, the ship was heavily influenced by the earlier vessel, particularly in the vessel's comparatively short and wide hull. The Chilean ironclad Capitán Prat, then being built in the same shipyard and also designed by Lagane, also proved to be influential. Capitán Prat's secondary battery was mounted in twin-gun turrets to save weight and space, and Lagane adopted that innovation for Jauréguiberry, the first time such an arrangement was used on a French battleship. Like her other French contemporaries, she was unstable and suffered from poor seakeeping, a result of their limited displacement.[29]

As with the other battleships built during this period, Jauréguiberry had a relatively uneventful peacetime career. She suffered several minor accidents, including a pair of accidental explosions of torpedo compressed air chambers in 1897 and 1905.[30] Also in 1897, she joined Charles Martel and Carnot in the International Squadron for operations off Crete.[13] In 1913, the ship was assigned to the Training Division, thereafter serving with the Special Division in 1914. After the outbreak of World War I, the ship was sent to cover troopship convoys from North Africa to France and was later stationed in the Syrian Division in early 1915. Jauréguiberry then joined the Dardanelles Division for operations against the Ottoman Empire, including supporting the Landing at Cape Helles in April 1915. She then returned to Syria, where she remained largely until 1918 when she was reduced to reserve status. Decommissioned in 1919, she was converted into a barracks ship in 1920 and was ultimately broken up in 1934.[31][32]

| Ship | Armament[33] | Armor[34] | Displacement[34] | Propulsion[34][35] | Service[36] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Jauréguiberry | 2 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1887 guns 2 × Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1887 guns |

400 mm (15.7 in) | 11,818 t (11,631 long tons) | 2 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17.5 kn | 23 April 1891 | 16 February 1897 | Broken up, 1934 |

Masséna

[edit]

Masséna was designed by Louis de Bussy, who had also designed the revolutionary armored cruiser Dupuy de Lôme; like the other members of the 1890 program, Masséna was built within the same displacement limitations and accordingly suffered from the same stability and seakeeping problems. She also retained the same lozenge arrangement of her half-sisters. The ship introduced one significant innovation to French capital ship design: the three-shaft arrangement for her propulsion system. All previous French capital ships had used two screws. She was also the first ship to mount the improved 1893 versions of the 305 mm and 274 mm main guns—albeit of an experimental 45-caliber (cal.) version that was later reduced to 40-cal. in later vessels—that was to equip all French battleships for more than a decade.[37][38]

The ship's career was uneventful; she served as the flagship of the Northern Squadron for her first years in service. In 1903, she was transferred to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Squadron. For the next several years, she was periodically reactivated to take part in training exercises with the rest of the fleet, before being reduced to reserve again in 1913.[39] Hulked in 1915,[40] Masséna was ultimately scuttled in November 1915 to form a breakwater to protect the vessels that evacuated the Allied army that had been defeated in the Gallipoli campaign.[25]

| Ship | Armament[40] | Armor[41] | Displacement[41] | Propulsion[41] | Service[25][40][41] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Masséna | 2 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns 2 × Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns |

450 mm (17.7 in) | 11,920 t (11,735 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17 kn | September 1892 | June 1898 | Scuttled, 9 November 1915 |

Bouvet

[edit]

Bouvet was the last and most successful member of the 1890 program; she was the third vessel designed by Huin. He used the experience gathered with Charles Martel to produce an improved version in an attempt to correct the faults of the other vessels ordered under the program. Bouvet's superstructure was smaller than the other vessels, and though she was not as top-heavy as the other ships, she still had insufficient stability, which contributed to her eventual loss in 1915. This was largely a result of the pronounced tumblehome and an insufficiently subdivided hull that was not able to cope with underwater damage. The ship was the first major French warship to be completed with an integrated fire-control system that coordinated the rangefinders, observers, and the gun crews with a central command post to direct the aiming of her main guns.[42]

Bouvet spent her career in the Mediterranean Squadron, occupied primarily with training exercises and cruises. In 1903, she was involved in a collision with the battleship Gaulois that saw both vessels slightly damaged and both ships' captains relieved of duty. She assisted with relief efforts after Mount Vesuvius erupted in 1906 and the following year she was transferred to the 2nd Battle Squadron, part of what was then the Mediterranean Fleet. Unlike her four half-sisters, she remained in active service with the fleet at the outbreak of World War I, and after covering convoys from North Africa, she was sent to the Dardanelles. From February to March 1915, she participated in several attacks on the Ottoman coastal fortifications guarding the straits, culminating in a major attempt to force the straits on 18 March. During the battle, Bouvet was heavily engaged by Ottoman artillery, suffered eight hits, but had neutralized one fortress's guns before she struck a naval mine that caused uncontrolled flooding. She capsized and sank with heavy loss of life; 24 officers and 619 enlisted men were killed in the sinking.[40][43][44]

| Ship | Armament[45] | Armor[46] | Displacement[47] | Propulsion[48] | Service[49] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Bouvet | 2 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns 2 × Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns |

400 mm | 12,200 t (12,007 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 18 kn | 16 January 1893 | June 1898 | Sunk during operations off the Dardanelles on 18 March 1915 |

Charlemagne class

[edit]

The Minister of the Navy, Auguste Burdeau, instructed the naval design staff to prepare a new battleship proposal that was limited to 11,000 t (11,000 long tons) in 1892. The weight reduction was to be achieved by returning to twin-gun turrets for the main battery, which would halve the number of turrets and thus reduce the weight that would be expended armoring them. Burdeau initially suggested a battery of two 305 mm guns in a turret forward and two 274 mm guns in a turret aft, but it was determined that the smaller gun would be incapable of penetrating the armor on the latest British battleships, so a uniform battery of 305 mm guns was adopted. The Navy requested several proposals for the new ships, but negative experience with the experimental series of battleships ordered under the 1890 program led to a decision to build three ships to the same plan. During the design process, the various designers found it difficult to stay within the 11,000-ton limit while incorporating the necessary offensive and defensive characteristics. The naval command accepted the growth of the design and in 1893 selected the proposal prepared by Jules Thibaudier, the director of the Arsenal de Rochefort shipyard, with construction beginning on the first of three vessels later that year.[50]

The first two ships—Gaulois and Charlemagne—were briefly assigned to the Northern Squadron before being moved to the Mediterranean Squadron in 1899, where they were joined by Saint Louis the next year. The last member of the class became the squadron flagship. The ships were involved in a number of accidents: Gaulois collided with the destroyer Hallebarde in 1900 and Bouvet in 1903, Saint Louis was struck by the destroyer Poignard and rammed the submarine Vendémiaire in 1911 and 1912, respectively. The new battleship Suffren replaced Saint Louis as the flagship in 1904, and the three Charlemagnes were moved to the North Sea in 1909 and returned to the Mediterranean in 1912. They escorted convoys at the start of World War I and later took part in the Dardanelles campaign, where Gaulois was badly damaged by Ottoman artillery fire. Gaulois was later torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat in 1916 and the other two vessels saw little activity thereafter, being withdrawn from service in mid-1917.[51] Charlemagne was sold for scrap in 1923,[52] while Saint Louis remained in the navy's inventory as a barracks ship until 1931, when she was struck from the naval register and sold two years later.[53]

| Ship | Armament[54] | Armor[54] | Displacement[55] | Propulsion[54][55] | Service[55][56][57][58] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Charlemagne | 4 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns | 400 mm | 11,275 t (11,097 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 18 kn | 2 August 1894 | 12 September 1899 | Broken up, 1923 |

| Saint Louis | 25 March 1895 | 1 September 1900 | Broken up, 1933 | ||||

| Gaulois | 6 January 1896 | 15 January 1899 | Sunk by UB-47, 27 December 1916 | ||||

Iéna

[edit]

The Board of Construction requested an improved version of the Charlemagne class in 1897, which was to correct the stability problems that perennially plagued French battleships of the period. The Navy Minister asked Thibaudier to design a larger version of the ship, with displacement increased to 12,000 t, as the naval staff had determined that, like the ships of the 1890 program, the Charlemagnes represented an attempt to fit too much into a limited displacement. Thibaudier prepared the next design, which was in many respects a simple repeat of the Charlemagnes, incorporating relatively minor improvements, including a more effective armor layout (the result of using Harvey armor to reduce the thickness but not the effectiveness of armor) and a heavier secondary battery. Iéna retained the pronounced tumblehome of the earlier French battleships, which was a primary cause of the ships' poor stability. She was nevertheless a good sea-boat and very maneuverable.[59][60]

On entering service, Iéna became the flagship of the 2nd Battle Division in the Mediterranean Squadron. She thereafter embarked on the routine of training exercises and cruises with the rest of the fleet. Her career passed uneventfully, apart from a collision with a torpedo boat off Toulon in 1906 that resulted in the latter's sinking. The ship's career was cut short in March 1907 when, while in drydock in Toulon, a magazine explosion destroyed the ship. An investigation blamed Poudre B, the smokeless propellant used by the French Navy for its shells. The wreck was repaired to make her watertight and was refloated in 1909 for use as a target ship, being partially broken up between 1913 and 1914 off Porquerolles, though parts of the ship remained there until 1957 when final demolition was completed.[61]

| Ship | Armament[62] | Armor[62] | Displacement[62] | Propulsion[62] | Service[63] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Iéna | 4 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns | 320 mm (12.6 in) | 12,105 t (11,914 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17 kn | 15 January 1898 | 14 April 1902 | Destroyed by magazine explosion, 12 March 1907 |

Suffren

[edit]

The Navy Minister issued a request for a new battleship in 1898 that was to be an improved version of the basic Charlemagne/Iéna design. The funding for the ship had already been authorized and so displacement was limited to the same as that of Iéna. As a result, Thibaudier was constrained in what he could accomplish with the design, and so he considered improvements to stability, the caliber and arrangement of the secondary battery, and the armor layout of the hull. He considered the use of twin-gun turrets for the secondary battery, but concerns over the risk that damage would disable two guns rather than just one and the arrangement for effective fields of fire led the command to reject them. Requests from the various technical sections of the French Navy for increased ammunition storage, improved armor for the secondary battery, and accommodations for a flag officer and his staff complicated Thibaudier's task. As a result of the competing requests, the secondary battery could only be strengthened by the addition of a pair of guns. Increases in the ship's length necessitated improvements to the Arsenal de Brest shipyard before work could begin.[64]

Suffren became the flagship of the 1st Battle Division after her commissioning. Her peacetime career was marked by a number of accidents: she collided with Saint Louis in 1905 and the submarine Bonite in 1906, nearly sinking the latter. She was moored next to Iéna when the latter vessel exploded in 1907; the blast hurled burning fragments that set Suffren on fire. She broke her starboard propeller shaft while underway in 1910 and lost power during maneuvers in 1911 and collided with the battleship Démocratie, though she was not seriously damaged in any of these incidents. During World War I, she took part in the Dardanelles campaign through the end of 1915. In 1916, she joined the main French fleet in Greek waters, where she saw little activity. While en route to Lorient for a refit in November 1916, she was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-boat U-52 off the coast of Portugal, killing her entire crew.[65][66]

| Ship | Armament[67] | Armor[67] | Displacement[67] | Propulsion[67] | Service[68] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Suffren | 4 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns | 300 mm (11.8 in) | 12,892 t (12,688 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 17 kn | 5 January 1899 | 3 February 1904 | Sunk by U-52, 26 November 1916 |

République class

[edit]

The two République-class ships were ordered under the 1900 Fleet Law, which was a reaction to the German 1898 Naval Law; the French law called for six new battleships, which were initially to be a homogeneous class. Louis-Émile Bertin prepared the design for the new ships, with an allowed displacement of up to 15,000 t (15,000 long tons), a major increase over earlier vessels. Bertin correctly perceived the flaws of the narrow belt armor of earlier French battleships, and so designed what was to become République with a more comprehensive arrangement. Developments with heavier secondary batteries abroad, particularly with the British King Edward VII-class battleships, led to the last four ships being redesigned with more powerful secondary guns, resulting in four-ship Liberté class. Like many late French pre-dreadnoughts, their lengthy design and construction periods resulted in their completion after the revolutionary British "all-big-gun" battleship HMS Dreadnought.[69][70]

Both vessels served with the Mediterranean Fleet throughout their careers, initially with the 1st Squadron and, after the Danton-class ships entered service, with the 2nd Squadron. They took part in convoy escort operations in the first days of World War I and then deployed to the southern Adriatic Sea to engage the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The Austro-Hungarians refused to take the bait, and the French only caught the small protected cruiser Zenta, which they sank in the Battle of Antivari. République and Patrie were later involved in Allied efforts to force Greece to enter the war against Germany and Austria-Hungary, which ultimately succeeded in 1917. République was partially disarmed in early 1918 to provide guns for the French Army and thereafter became a training ship, but Patrie remained in service until 1919, when she, too, was reduced to a training role. The lead ship was sold for scrap in 1921, but Patrie was retained for training purposes until 1936, when she was finally decommissioned and sold the following year.[71]

| Ship | Armament[72] | Armor[72] | Displacement[72] | Propulsion[72] | Service[73] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| République | 4 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns | 280 mm (11 in) | 14,605 t (14,374 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 18 kn | 27 December 1901 | 12 January 1907 | Broken up, 1921 |

| Patrie | 14,900 t (14,700 long tons) | 1 April 1902 | 1 July 1907 | Broken up, 1937 | |||

Liberté class

[edit]

Initially meant to be identical to the Républiques, the four Liberté-class ships were redesigned after foreign battleships began to carry heavier secondary guns; these included the British King Edward VII class, armed with 9.2 in (230 mm) secondaries, which were in turn a response to American and Italian battleships armed with 203 mm (8 in) guns. Accordingly, the Naval General Staff requested the last four members of the 1900 program to be redesigned to carry 194 mm guns. Ironically, Bertin had suggested the exact same caliber during the initial design process, which the General Staff rejected over fears that the rate of fire would fall. The two classes were otherwise nearly identical, which has led some historians, including John Jordan and Philippe Caresse, to consider them to be one class with two variants.[74][75]

The four ships' service history largely mirrored that of the République class. In 1909, Liberté, Justice, and Vérité traveled to the United States for the Hudson–Fulton Celebration and, in 1911, they joined the Républiques in the 2nd Squadron. In September that year, Liberté was destroyed by an accidental explosion while moored in Toulon; the cause of the blast was determined to be the same unstable Poudre B that had destroyed Iéna in 1907. Along with their squadron mates, the three surviving Libertés escorted convoys early in World War I and took part in the Battle of Antivari.[76] Vérité briefly took part in operations against the Ottomans in November and December,[77] and later took part in the operations in Greece in 1916 and early 1917. After securing Greece's alliance, the ships returned to the fleet's main wartime anchorage at Corfu, where it remained for the rest of the war. Immediately after the German surrender, Justice and Démocratie were sent to the Black Sea to oversee German demilitarization and then to take part in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. War-weary sailors later mutinied in several vessels and forced the French to withdraw in 1919. The three ships saw no further significant service and all were discarded in 1921–1922[78]

| Ship | Armament[79] | Armor[79] | Displacement[79] | Propulsion[79] | Service[73] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Liberté | 4 × Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns | 280 mm | 14,900 t (14,700 long tons) | 3 shafts, triple-expansion engines, 18 kn | November 1902 | 13 April 1908 | Destroyed by magazine explosion, 25 September 1911 |

| Justice | 1 April 1903 | 15 April 1908 | Broken up, 1922 | ||||

| Vérité | April 1903 | 11 September 1908 | Broken up, 1921 | ||||

| Démocratie | 1 May 1903 | 9 January 1908 | Broken up, 1921 | ||||

Danton class

[edit]

Following the beginning of construction of Liberté, France began planning for the next major construction program. By this time, France had concluded the Entente Cordiale with Britain, and the increasingly powerful German fleet was viewed as the most significant threat; the program of 1906 called for a total of sixteen new battleships to be built by 1919 to counter the Germans. In an effort to control the cost of the next ships to be built, the Minister of the Navy, Gaston Thomson, imposed a limit of 18,000 t (18,000 long tons). The design staff began its work in the aftermath of the Battle of Tsushima; the French Navy determined that Japanese success in the battle had been the result of the high speed of their ships and the large number of medium-caliber guns that inflicted significant damage to the unarmored superstructures of the Russian warships. As a result, the navy decided to adopt a heavier secondary battery than the preceding Libertés, but decided against following many other major navies then building "all-big-gun" battleships. The naval command determined that replacing the planned 240 mm (9.4 in) guns with single 305 mm guns would have increased displacement over the limit and reduced the rate of fire. The navy did introduce a new, longer 45-cal. version of the 305 mm gun, the Modèle 1906 type. Pressure from Parliament to keep technological pace with foreign navies led the designers to adopt steam turbines, the first time they were used in French capital ships. The navy had initially intended to build three ships as the first stage of the program, but delays during the design process led to the authorization of six ships to account for the slowdown.[80][81]

After entering service in 1911, all six ships were assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron, where they remained until the outbreak of World War I. Like the rest of the fleet, they escorted convoys from North Africa at the start of the war and then went to the Adriatic, seeing action at the Battle of Antivari, with the exception of Mirabeau, which was being refitted in Toulon at the time. The six Dantons remained based at Corfu and Malta for much of the war to blockade the Austro-Hungarian fleet. During this period, portions of the ships' crews were stripped to provide men for anti-submarine warships to combat the German and Austro-Hungarian U-boats; combined with coal shortages that curtailed operations, the reduction in crews led to crippling morale problems for the fleet. In March 1917, Danton was sunk by a German U-boat. After the war, the surviving ships participated in the intervention in Russia in 1919 and Mirabeau was damaged after running aground off the Crimea; she was never repaired and was eventually broken up.[82][83] The other vessels were modernized in the early 1920s, with the exception of Vergniaud, which was in poor condition. They continued on in secondary roles into the 1930s, and Condorcet remained in use as a depot ship until 1942, when she was captured by German forces in Toulon, ultimately being bombed and sunk in 1944.[84]

| Ship | Armament[85] | Armor[85] | Displacement[85] | Propulsion[85] | Service[86] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Danton | 4 × 305mm/45 Modèle 1906 guns | 250 mm (9.8 in) | 18,754 t (18,458 long tons) | 4 shafts, steam turbines, 19.25 kn (35.65 km/h; 22.15 mph) | 9 January 1908 | 24 July 1911 | Sunk by U-64 on 19 March 1917 |

| Condorcet | 23 August 1907 | 25 July 1911 | Sunk, August 1944 | ||||

| Diderot | 20 October 1907 | 25 July 1911 | Broken up, 1937 | ||||

| Mirabeau | 4 May 1908 | 1 August 1911 | Broken up, 1928 | ||||

| Vergniaud | July 1908 | 18 December 1911 | Broken up, 1928 | ||||

| Voltaire | 8 June 1907 | 5 August 1911 | Broken up, 1949 | ||||

Dreadnought battleships

[edit]Courbet class

[edit]

The French naval command had become convinced by 1909 that the so-called dreadnought battleships were superior to the mixed-battery ships like the Dantons, and so the new naval minister, Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère, instructed the design staff to prepare an all-big-gun proposal. Displacement was limited to 21,000 t (21,000 long tons), which corresponded to contemporary foreign dreadnoughts. Consideration was given to uniform batteries of 240, 274, and 305 mm guns; the Technical Section prepared three designs, the first of which was essentially a repeat Danton with increased ammunition storage, the second was a Danton variant with the six 240 mm wing turrets replaced by four 305 mm turrets, bringing the total number of guns to twelve. The turrets were arranged in a superfiring pair forward, two wing turrets amidships, and another superfiring pair aft. The third version included a mix of twin and triple turrets, but Boué de Lapeyrère ordered a modified version of the second proposal, and the first two ships were ordered for the 1910 budget. Two more followed in 1911.[87]

Three of the four ships were completed shortly before World War I, and France and Jean Bart carried President Raymond Poincaré on a visit to Russia during the July Crisis, the proximate cause of the war. The ships operated with the main fleet during the conflict and saw little activity after the Battle of Antivari; they suffered the same fate as the Dantons, with crews being thinned to provide men for more important vessels. France and Jean Bart were involved in the intervention in Russia in 1919 and after returning to France later that year, were assigned to the new Western Mediterranean Squadron. In 1922 France struck an uncharted rock in Quiberon Bay and sank. The three surviving ships were refitted in the late 1920s and early 1930s. They thereafter served in secondary roles, including as training ships and later as barracks ships. Courbet remained in service as a training vessel early in World War II and she shelled German forces during the Battle of France in June 1940 before fleeing to Britain and eventually being sunk as a breakwater for the Normandy invasion. Jean Bart, which had been renamed Océan in 1937, was seized by the Germans in 1942 and used for weapons tests before being bombed and sunk in 1944. Paris, the last surviving member of the class, was also evacuated to Britain after the German invasion and was used as a depot ship first in Britain and then in France until 1955.[88]

| Ship | Armament[89] | Armor[89] | Displacement[89] | Propulsion[89] | Service[90] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Courbet | 12 × 305mm/45 Modèle 1906 guns | 250 mm | 25,579 t (25,175 long tons) | 4 shafts, steam turbines, 21 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph) | 1 September 1910 | 19 November 1913 | Sunk as a breakwater, 9 June 1944 |

| Jean Bart | 15 November 1910 | 19 November 1913 | Broken up, 1945 | ||||

| Paris | 10 November 1911 | 1 August 1914 | Broken up, 1956 | ||||

| France | 30 November 1911 | 10 October 1914 | Wrecked, 1922 | ||||

Bretagne class

[edit]

The Bretagne class was modeled on the preceding Courbet class, using the same hull design as a result of the size constraints of French shipyards. Design work began before the Courbets had been ordered, and the emphasis was on increasing the caliber of the main battery to match foreign development of the so-called superdreadnought type such as the British Orion class.[91] The naval high command initially specified a maximum displacement of 23,500 t (23,100 long tons) and a main battery of twelve 340 mm (13 in) guns. The 340 mm turrets were significantly heavier than the 305 mm versions used in the Courbets, and the design staff found it impossible to retain six turrets within the prescribed displacement. They submitted a five-turret design, removing one of the wing turrets and moving the other to the centerline amidships, which kept the same ten-gun broadside. In addition, the belt armor was reduced slightly to accommodate for the greater weight of the main battery.[92][93][94] A new naval law was passed in 1912 that projected a fleet of twenty-eight battleships by 1920; three ships were authorized for the 1912 budget, which became the Bretagnes.[91]

Upon completion, the ships were assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron and sent to join the fleet at Corfu; by this point, the fleet had settled into the blockade of the southern Adriatic and so the Bretagnes saw little activity during the war. The ships spent the 1920s and 1930s in the Mediterranean and Atlantic Squadrons, undergoing periodic refits and modernizations, and in the late 1930s, they took part in the non-intervention patrols off Spain during the Spanish Civil War. After the start of World War II, they operated as convoy escorts in the Atlantic and in 1940, as war with Italy became increasingly likely, they were concentrated with the bulk of the French fleet in the Mediterranean as a deterrent. Bretagne and Provence were in Mers El Kébir when Germany defeated France in June 1940, and during a British operation to neutralize the French fleet, were attacked in the port by the British Force H. Bretagne was destroyed and Provence was badly damaged, later being refloated and returned to Toulon for repairs, where she was scuttled in 1942 to prevent her capture by the Germans. Meanwhile, Lorraine was seized by the British while she was moored in Alexandria, Egypt and then turned over to the Free French Naval Forces. She saw action during the last years of the war bombarding German forces in occupied France. After the war, she was used as a training vessel and later a barracks ship, ultimately being scrapped in 1953.[95][96][97]

| Ship | Armament[98] | Armor[98] | Displacement[98] | Propulsion[98] | Service[99] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Bretagne | 10 × 340mm/45 Modèle 1912 guns | 250 mm | 26,600 t (26,200 long tons) | 4 shafts, steam turbines, 21 kn | 22 July 1912 | 10 February 1916 | Sunk at the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, 3 July 1940 |

| Provence | 21 April 1912 | 1 March 1916 | Broken up, 1949 | ||||

| Lorraine | 7 November 1912 | 10 March 1916 | Broken up, 1953 | ||||

Normandie class

[edit]

Before work on the Bretagne class had even begun, the French Navy's Technical Committee issued a report in late 1911 criticizing the decision to adopt a centerline, amidships turret based on previous experience with ships in the 1880s; the center turret inflicted excessive blast damage on the superstructure. Work on the next design began in early 1912 and three initial versions were prepared; the first was essentially a repeat of Bretagne but the other two attempted a radical solution to the problem identified by the Technical Committee. To avoid the central turret, they proposed a new quadruple turret; the first variant used two of these turrets, each with a twin-turret superfiring above them, and the second incorporated four quadruple turrets with 305 mm guns. The General Staff decided to retain the 340 mm gun and preferred the quadruple turret if development could be completed in time, ultimately settling on a finalized version equipped with three quadruple turrets, one forward and two aft. The 1912 naval law had initially called for two ships to be ordered in 1913 and two more in 1914, but an amendment increased the pace to four in 1913 and a fifth in 1914, owing to the increased tension in Europe during this period.[100]

The first two ships were ordered in April 1913, followed by two more in July, and a fifth vessel in January 1914. Work was halted after the outbreak of war, as resources were diverted to more critical projects for the Army and to complete the Bretagnes, then much further along in construction. Much of the material that had been assembled for the ships was used for other purposes, including boilers to replace those of older vessels, and main guns converted into railway guns for the Army. After the war, the first four ships were cancelled and parts of those vessels were used to complete Béarn as an aircraft carrier. She remained in service during World War II and the French Indochina War and was ultimately scrapped in 1967.[92][101][102]

| Ship | Armament[103] | Armor[103] | Displacement[103] | Propulsion[103] | Service[104][92][105] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Normandie | 12 × 340 mm /45 Modèle 1912 guns | 300 mm | 28,270 t (27,820 long tons) | 4 shafts, triple-expansion engines and steam turbines, 21 kn | 18 April 1913 | — | Broken up, 1924 |

| Flandre | 1 October 1913 | Broken up, 1924 | |||||

| Gascogne | 1 October 1913 | Broken up, 1923 | |||||

| Languedoc | 1 May 1913 | Broken up, 1929 | |||||

| Béarn | 5 January 1914 | May 1927 | Broken up, 1967 | ||||

Lyon class

[edit]

The amendment to the 1912 naval law called for four ships to be ordered in 1915. Design work for the new vessels began in mid-1913, and since longer graving docks would soon be completed in Brest and Toulon, the new ships would not be limited by infrastructure. The naval command considered increasing the caliber to 380 mm (15 in) to keep pace with the latest British battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class, but the French did not yet have a gun of that caliber completed, and the delays necessary to design and test it were deemed unacceptable. Additionally, the French expected to be fighting at ranges where the existing 340 mm gun was able to defeat heavy armor, so there was little need to step up to the larger caliber. The 340 mm gun was adopted, but to improve the ships' firepower, a fourth quadruple turret was added. The ships were allocated to shipyards in late 1913, with work to begin on the first two in January 1915, with the second pair to follow at an unspecified time. Work to complete the design continued into 1914, but the details of the ships' underwater protection system had not yet been finalized by the time war broke out in August 1914. With the start of the war, the project was cancelled; no work was done and no material was assembled for the vessels.[106]

| Ship | Armament[107] | Armor[108] | Displacement[108] | Propulsion[108] | Service[109] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Lyon | 16 × 340 mm /45 Modèle 1912 guns | 300 mm | 29,600 t (29,100 long tons) | 4 shafts, unknown type, 21 kn | — | — | — |

| Duquesne | |||||||

| Lille | |||||||

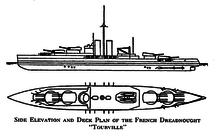

| Tourville | |||||||

Fast battleships

[edit]Dunkerque class

[edit]

In the early 1920s, the major naval powers concluded the Washington Naval Treaty to limit battleship construction; under the terms of the treaty, France was limited to a total of 175,000 long tons (178,000 t) of battleship tonnage. All members of the treaty system were barred from building battleships for a decade, apart from France and Italy, both of which had 70,000 long tons (71,000 t) allotted, since their fleets consisted of older vessels. Financial weakness after the war, coupled with indecision over what type of ship to build delayed the construction of new French battleships. The navy initially conceived of small, fast battleships to counter new Italian heavy cruisers that threatened France's lines of communication in the Mediterranean. The advent of the German Deutschland-class cruisers, armed with 283 mm (11.1 in) guns, necessitated larger, more capable battleships, with armor heavy enough to defeat the German large-caliber guns. This process eventually produced the Dunkerque class.[110]

Dunkerque and Strasbourg were commissioned in the late 1930s; they spent the majority of their peacetime years conducting training. Following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 that started World War II, the ships were initially used as part of the Force de Raid (Raiding Force) to hunt down German commerce raiders and to escort convoys. The ships were moored in Mers El Kébir to deter Italy from joining the war when Germany defeated France in May and June 1940, and were to be demilitarized there under the terms of the Armistice of 22 June 1940. Concerned that the Germans would seize the French fleet, the British launched Operation Catapult to neutralize the vessels; during the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, Force H damaged Dunkerque but Strasbourg was able to escape the harbor and reach Toulon. After a second attack that sank her, Dunkerque was refloated and returned to Toulon as well, before both ships were ultimately scuttled in the harbor to prevent the Germans from seizing them in 1942. Both vessels were eventually broken up in the 1950s.[111][112]

| Ship | Armament[113] | Armor[114] | Displacement[115] | Propulsion[116] | Service[117] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Dunkerque | 8 × 330 mm (13 in) /50 Modèle 1931 guns | 225 mm (8.9 in) | 35,500 t (34,900 long tons) | 4 shafts, steam turbines, 29.5 kn (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph) | 24 December 1932 | 31 December 1936 | Broken up, 1958 |

| Strasbourg | 238 mm (9.4 in) | 36,380 t (35,810 long tons) | 24 November 1934 | 15 September 1938 | Broken up, 1955 | ||

Richelieu class

[edit]

The Italian response to the Dunkerques, the first two Littorio-class battleships, which displaced 35,000 long tons (36,000 t) and were armed with nine 380 mm guns, prompted France to respond in kind. The French considered a scaled-up version of the Dunkerque design armed with eight 380 mm or 406 mm (16 in) guns, or a version with three triple-turrets. The design staff quickly determined that the weight of the 406 mm battery would preclude the other technical requirements for the ships and decided that 380 mm was the largest caliber that could be carried in the specified displacement. The design was finalized by August 1935 and two ships were ordered and quickly laid down; because the ships were larger than the shipyards available, the builders adopted a plan to build the bulk of the hull on the slipway and then add bows and sterns after moving them to drydocks. Beginning construction of the ships in late 1935 placed France in violation of the naval arms treaty, as the total tonnage exceeded the 70,000 tons allowed before the building holiday expired in 1936. But the French government had objected to Britain failing to uphold its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles by signing a separate Anglo-German Naval Agreement earlier in 1935, which directly undermined the limitations of German armament imposed by Versailles. Two more ships, to be built to modified designs, were projected, but only Clemenceau was laid down before the start of the war. She was quickly cancelled, as was the fourth vessel, Gascogne.[118]

Neither Richelieu or Jean Bart was ready in time to see action before France was defeated in 1940. Jean Bart was moved to Casablanca and Richelieu fled to Dakar before they could be captured by German forces. The latter was attacked by British forces in July and September to prevent her from being turned over to the Germans, but Jean Bart was far from complete and so was ignored. In November 1942, the Allies invaded French North Africa and Jean Bart initially fired on the invasion fleet before being disabled by the US battleship Massachusetts. After the invasion, which resulted in French forces in North Africa turning to Free France, Richelieu was sent to the United States to be completed and modernized. She thereafter served with the British Home Fleet in the Indian Ocean and later in French Indochina, where she ended the war. Jean Bart was finally completed after the war; both vessels continued on in service with the French fleet, primarily as training vessels, before being decommissioned in 1968 and broken up.[119]

| Ship | Armament[120] | Armor[121] | Displacement[120] | Propulsion[120] | Service[122] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Richelieu | 8 × 380 mm (15 in) /45 Modèle 1935 guns | 327 mm (12.9 in) | 44,698 t (43,992 long tons) | 4 shafts, steam turbines, 32 kn (59 km/h; 37 mph) | 22 October 1935 | 1 April 1940 | Broken up, 1968 |

| Jean Bart | 12 December 1936 | 1 August 1949 | Broken up, 1970 | ||||

| Clemenceau | 320 mm | 17 January 1939 | — | Broken up, 1951 | |||

| Gascogne | — | — | — | ||||

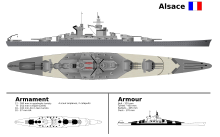

Alsace class

[edit]

After work on the Richelieus began and the international naval treaty system fell apart following Japan's and Italy's refusal to sign the Second London Naval Treaty, the French Navy began design studies on the next class of battleships that would take advantage of the escalator clause in the treaty that allowed displacement to be increased to 45,000 long tons (46,000 t) and the main battery to be increased to 406 mm (the treaty had added a limit of 356 mm (14 in) guns). The design staff prepared several studies in 1939, all of which were derivatives of the three-turret design that had been drawn up during the Richelieu design process. The first variant had nine 380 mm guns in triple turrets, with slightly improved protection over the Richelieus and a more powerful secondary battery. The second version was essentially the same, but scaled up for 406 mm guns, and the third featured three quadruple 380 mm turrets. The navy settled on the first version, as the second variation would have introduced a fourth shell caliber to the fleet, thus complicating logistics, and the third design was too large and expensive. Two ships were authorized in April 1940, with construction to begin in 1941 after the aircraft carrier Joffre was launched, but following the French collapse in June, the program was cancelled.[123]

| Ship | Armament[124] | Armor | Displacement[124] | Propulsion[124] | Service[124] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Alsace | 9 × 380 mm /45 Modèle 1935 guns | 330 mm | 41,000 t (40,000 long tons) | Unknown, estimated 31 kn (57 km/h; 36 mph) | — | — | — |

| Unnamed | |||||||

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Ropp, pp. 222–223, 230.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 20, 217–219, 223.

- ^ a b Smigielski, p. 191.

- ^ Campbell, p. 292.

- ^ a b Caresse 2019, p. 30.

- ^ Caresse 2019, p. 31.

- ^ Caresse 2019, p. 32.

- ^ Caresse 2019, p. 35.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Ropp, p. 223.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 32, 38–40.

- ^ a b c Robinson, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 217–219, 223–224, 232, 239.

- ^ a b c Campbell, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 26.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 22–25, 28–29.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Brassey 1903, p. 57.

- ^ Brassey 1904, p. 89.

- ^ Palmer, p. 171.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 229, 232, 239.

- ^ a b c d Smigielski, p. 192.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 27.

- ^ a b Jordan & Caresse, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Jordan & Caresse, p. 28.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 25, 29–30, 38–40.

- ^ d'Ausson, pp. 22–23.

- ^ d'Ausson, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 239, 252–254, 266–267.

- ^ Gibbons, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Jordan & Caresse, p. 30.

- ^ d'Ausson, p. 23.

- ^ d'Ausson, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 25, 32, 38–40.

- ^ Friedman, p. 203.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 217, 223.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, p. 294.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 32.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 25, 32–33, 35–40.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 217–223, 252–254, 263.

- ^ Corbett 1921, pp. 142–149, 158–161, 215–219.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 33.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 38.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 32, 263.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 218–229, 252–253, 261–267, 279.

- ^ Silverstone, p. 92.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 280.

- ^ a b c Caresse 2012, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Gille, p. 98.

- ^ Caresse 2012, pp. 116, 134.

- ^ Silverstone, pp. 92, 111.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 44.

- ^ Caresse 2007, p. 121.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 64–66, 74.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 220–225.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 67.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 66, 224.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 222–224.

- ^ Caresse 2010, pp. 16–26.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 75.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 75, 270.

- ^ Ropp, p. 329.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 223, 225–226, 231–234, 274, 276–277, 285–286.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 89.

- ^ a b Jordan & Caresse, pp. 88, 285–286.

- ^ Burt, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 223, 225–226, 231–238, 252–258.

- ^ Corbett 1920, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 269–270, 274, 276–277, 285–286.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 101.

- ^ Jordan, pp. 46–49, 53, 65.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 113–116, 139.

- ^ Gille, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 274–278.

- ^ Meirat, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 119.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 116, 275, 287–288.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 252–258, 274–278, 288–301.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 143.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 142, 290, 319–320.

- ^ a b Jordan & Caresse, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Smigielski, p. 198.

- ^ Dumas, p. 74.

- ^ Whitley, p. 40.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 244–245, 275–277.

- ^ Whitley, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Roberts, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 163.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 163, 314, 320–321.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 162, 184–185, 188–189.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 189, 202, 300.

- ^ Friedman, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Caresse, p. 191.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 189.

- ^ Roberts, p. 261.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, pp. 162, 204–207.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Jordan & Caresse, p. 204.

- ^ Jordan & Caresse, p. 207.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 15–32.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 58–61, 65–70, 75, 77, 84–92.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 50.

- ^ Roberts, p. 259.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 38.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 59, 93.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 94–98, 163, 167, 176.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 122–126, 141–145, 154–156, 181–185, 221.

- ^ a b c Jordan & Dumas, p. 94.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 94, 167, 173.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 123, 171, 208, 222.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 178–181.

- ^ a b c d Jordan & Dumas, p. 180.

References

[edit]- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1903). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1904). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Burt, R. A. (2013) [1988]. British Battleships 1889–1904. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-173-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Caresse, Philippe (2007). "The Iéna Disaster, 1907". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2007. London: Conway. pp. 121–138. ISBN 978-1-84486-041-8.

- Caresse, Philippe (2010). "The Drama of the Battleship Suffren". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2010. London: Conway. pp. 9–26. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Caresse, Philippe (2012). "The Battleship Gaulois". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2012. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-156-9.

- Caresse, Philippe (2019). "The French Battleship Brennus". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2019. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 29–46. ISBN 978-1-4728-3595-6.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1920). Naval Operations: To The Battle of the Falklands, December 1914. Vol. I. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 174823980.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1921). Naval Operations: From The Battle of the Falklands to the Entry of Italy Into the War in May 1915. Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 924170059.

- de la Loge d'Ausson, Enseigne de Vaisseau (1976). "French Battleship Jaureguiberry". F.P.D.S. Newsletter. IV (3). F.P.D.S.: 22–24. OCLC 41554533.

- Dumas, Robert (1986). "The French Dreadnoughts: The 23,500 ton Bretagne Class". In Lambert, Andrew D. (ed.). Warship. Vol. X. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 74–85, 158–165. ISBN 978-0-85177-449-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garzke, William H. Jr. & Dulin, Robert O. Jr. (1980). British, Soviet, French, and Dutch Battleships of World War II. London: Jane's. ISBN 978-0-7106-0078-3.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships: A Technical Directory of Capital Ships from 1860 to the Present Day. New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-37810-6.

- Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français [A Century of French Battleships] (in French). Nantes: Marines édition. ISBN 2-909675-50-5.

- Jordan, John (2013). "The 'Semi-Dreadnoughts' of the Danton Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2013. London: Conway. pp. 46–66. ISBN 978-1-84486-205-4.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Jordan, John & Dumas, Robert (2009). French Battleships 1922–1956. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-034-5.

- Meirat, Jean (1978). "French Battleships Vergniaud and Condorcet". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. VI (1): 5–6. OCLC 41554533.

- Palmer, W., ed. (1908). "France". Hazell's Annual. London: Hazell, Watson & Viney, Ltd. OCLC 852774696.

- Roberts, John (1980). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 255–279. ISBN 978-0-85177-146-5.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (1897). "The Fleets of the Powers in the Mediterranean". The Navy and Army Illustrated. III. London: Hudson & Kearnes: 186–187. OCLC 7489254.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Smigielski, Adam (1985). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 190–220. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.

External links

[edit]