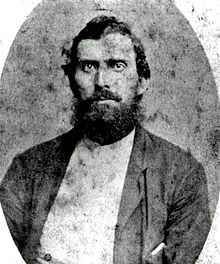

Newton Knight

Newton Knight | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captain of Knight Company | |

| In office October 13, 1863 – April 9, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 10, 1829 Jones County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | February 16, 1922 (aged 92) Jasper County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Resting place | Knight Cemetery, Jasper County, Mississippi |

| Political party | Republican[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Serena Turner Rachel Knight (common law) |

| Occupation | Farmer, former blacksmith, former soldier, U.S. Marshal |

Newton Knight (November 10, 1829 – February 16, 1922) was an American farmer, soldier and Southern Unionist in Mississippi, best known as the leader of the Knight Company, a band of Confederate Army deserters who resisted the Confederacy during the Civil War. Local legends tell of Knight and his men forming the "Free State of Jones" in the area in and around Jones County, Mississippi, at the height of the war. The nature and extent of the Knight Company's opposition to the Confederate government is disputed among historians. After the war, Knight joined the Republican Party and served in Mississippi's Reconstruction government as a deputy U.S. Marshal.

Knight has long been a controversial figure in the region, with people divided over his motives and actions. He and his allies developed a small mixed-race community in southeastern Mississippi.[2] His interracial marriage with Rachel Knight was considered illegal, as Mississippi had banned interracial marriages before and after the war, except for a brief period during Reconstruction.

Films about Knight have included Tap Roots (1948), directed by George Marshall, and Free State of Jones (2016), directed by Gary Ross and starring Matthew McConaughey as Knight.

Early life and education

My father was born on November 10, 1830, though the family records show it was 1833. His mother changed the record after he shot an African American boy to get him out of being punished in court. He was the eighth of the twelve boys, and was raised a poor farmer boy, making his living farming, also building houses for his neighbors.

Newton Knight was born near the Leaf River in Jones County, Mississippi, most likely in November 1837, to Albert Knight and his wife. His birth year has been recorded by his son, Tom Knight, in a biography as 1830, and his grandniece, Ethel Knight, wrote that he was born in 1829. His gravestone has his full name as "Capt. Newton Knight" born November 10, 1829, died February 16, 1922. But the 1900 census records that Knight was born in November 1837, likely from his own testimony.[citation needed][original research?] This date is consistent with census records from other years. However, it is possible Knight gave the wrong year of his birth to the census takers to hide his family origin.[4]: 243 [5] He was probably taught to read and write by his mother, as there were no public schools for yeomen children.[4]: 85

Newton was a grandson of John "Jackie" Knight (1773–1861), one of Jones County's largest slaveholders before the war. The first Knight forebear in America is believed to have emigrated to Yorktown from Worcestershire, England, in 1674. The family initially settled in Culpeper County, Virginia where they lived until the 1720s, when the family moved to Brunswick County, Virginia. In 1759, the family moved further south to Richmond County, North Carolina. In 1788, Knight's great-grandfather, William Knight, is understood to have moved to Dawson County, Georgia. John Jackie Knight moved to Mississippi in 1801, settling first in Union County, and then moving to the area of Jasper County in 1811 to establish plantations[4]: 62 Newton's father, Albert (1799–1862), however, neither owned slaves nor inherited any after his father's death.[6] Newton Knight never owned slaves.[4]: 64 His son wrote that he was morally opposed to the institution due to his Primitive Baptist beliefs. In accordance with its teachings, Newton forswore alcohol, unlike his father and grandfather.[1]

Newton Knight married Serena Turner in 1858, and the two established a small farm just across the county line in southwest Jasper County, Mississippi.[1]

Career

American Civil War

Jones County elected John H. Powell, the "cooperation" (anti-secession) candidate, to represent them at Mississippi's secession convention in January 1861. Powell voted against secession on the first ballot, but under pressure, switched his vote on the second ballot, joining the majority of whites in voting to secede from the Union. In an interview many years later, Knight suggested that many voters of Jones County, not understanding how limited Powell's choices were, felt betrayed by his action.[2][7]

Knight joined the Confederate Army in July 1861, enlisting in the 8th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Six months later he was given a furlough in order to return home and tend to his ailing father. In May 1862, Knight, along with a number of friends and neighbors, enlisted in Company F of the 7th Mississippi Infantry Battalion. They preferred to serve together in the same company, rather than with strangers.[4]: 99

Throughout the summer and fall of 1862, a number of factors increased the rate of desertions from the Confederate Army. There was a lack of food and supplies for soldiers in the aftermath of the siege of Corinth. The men of Jones County and the region were disturbed by news from home reporting the poor conditions, as their wives and children found it hard to keep up the farms. Knight was enraged when he received word that Confederate authorities had seized his family's horses for their use. However, many believe Knight's principal reason for desertion was his anger over the Confederate government's passing of the Twenty Negro Law. This act allowed large plantation owners to avoid military service if they owned 20 slaves or more. An additional family member was exempted from service for each additional 20 slaves owned by the planter. Knight had also received word that his brother-in-law, Morgan, who had become the head of the family in Knight's absence, was abusing Knight's children.[4]: 100–101 Morgan's identity has since been lost, but he is thought to have been Morgan Lines, a day laborer and convicted murderer.[8]

Knight was reported absent without leave in October 1862. He later defended his desertion, arguing, "if they had a right to conscript me when I didn't want to fight the Union, I had a right to quit when I got ready."[2] After making his way 200 miles home from deserting in the retreat following the defeat at Corinth, Knight, according to relatives, shot and killed Morgan.[4]: 100

In early 1863, Knight was arrested and jailed for desertion, and possibly tortured, by Confederate authorities.[9] They burned his homestead and farm as an example to others, leaving his family destitute.[4]: 104 [10]

As the ranks of deserters swelled after the Union was victorious in the siege of Vicksburg, Confederate authorities began receiving reports that deserters in the Jones County area were looting and burning houses.[11] A local quartermaster, Captain W. J. Bryant, reported that "the deserters have overrun and taken possession of the country, in many cases exiling the good and loyal citizens or shooting them in cold blood on their own door-sills."[12] General Braxton Bragg dispatched Major Amos McLemore to Jones County to investigate and round up deserters and stragglers. On October 5, 1863, McLemore was shot and killed in the Ellisville home of Amos Deason; Knight is believed to have killed him.[1]

Knight had taken to the swamp on the Leaf River to evade authorities, finding other deserters and fugitive slaves there. He and followers organized what they called the Knight Company on October 13, 1863. It was a band of guerrillas from Jones County and adjacent counties of Jasper, Covington, Perry and Smith, who intended to protect the families and farms from Confederate authorities, including high takings of goods for taxes.[2] Knight was elected "captain" of the company, which included many of his relatives and neighbors.[13] The company's main hideout, known as "Devils Den," was located along the Leaf River at the Jones-Covington county line. Local women and slaves provided food and other aid to the men. Women blew cattlehorns to signal the approach of Confederate authorities to their farms.[4]: 112

| A Rebel Soldier who recently deserted and came into our lines tells me that in the Tulahoma [Tallahoma] Swamps in Jones Co., Mississippi, there are some six hundred Deserters who are waiting for our forces to get near, so they can join them. They have deserted the Confederate cause and are determined to fight them to the last. All efforts from the Confederates to force them out have been unsuccessful and they are now offering a bounty to Deserters to join them. |

| —James Lamon, Union scout[14] |

From late 1863 to early 1865, the Knight Company allegedly fought fourteen skirmishes with Confederate forces. One skirmish took place on December 23, 1863, at the home of Sally Parker, a Knight Company supporter, leaving one Confederate soldier dead and two badly wounded.[4]: 107

During this same period, Knight led a raid into Paulding, where he and his men captured five wagonloads of corn, which they distributed among the local population.[4]: 112 The company harassed Confederate officials, with numerous tax collectors, conscript officers, and other officials being reported killed in early 1864.[1] In March 1864, the Jones County court clerk notified the governor that guerillas had made tax collections in the county all but impossible.[4]: 112 In 2016, a letter dated February 13, 1864, from a Union scout addressed to Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer of the Union Army was discovered by a historian working in the National Archives. It estimates the Knight Company's numbers to be as high as 600 and confirms their intention to join up with the Union Army.[14] The exact number is still a matter of debate, in light of an interview Knight gave after the war stating, "There was about 125 of us, never any more."[15]

By the spring of 1864, the Confederate government in the county had been effectively overthrown.[1] Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk wrote to Jefferson Davis on March 21, 1864, describing the conditions in Jones County. Polk stated that the band of deserters were "in open rebellion, defiant at the outset, proclaiming themselves 'Southern Yankees,' and resolved to resist by force of arms all efforts to capture them."[16] On March 29, 1864, Confederate Captain Wirt Thomson wrote to James Seddon, Confederate Secretary of War, claiming the Knight Company had captured Ellisville and raised the U.S. flag over the courthouse in Jones County. He further reported, "The country is entirely at their mercy."[17] General William Tecumseh Sherman received a letter from a local group declaring its independence from the Confederacy.[1] In July 1864, the Natchez Courier reported that Jones County had seceded from the Confederacy.[2]

General Polk initially responded to the actions of the Knight Company by sending a contingent under Colonel Henry Maury into the area in February 1864. Maury reported he had cleared the area, but noted the deserters had threatened to obtain "Yankee aid" and return.[2] Shortly afterward, Polk dispatched a veteran contingent of soldiers from the 6th Mississippi Infantry Regiment led by Colonel Robert Lowry, a future governor who would later describe Knight as an "ignorant and uneducated man."[18] Using bloodhounds to track down guerillas in the swamps, Lowry rounded up and executed ten members of the Knight Company, including Newton's cousins, Benjamin Franklin Knight and Sil Coleman. Newton Knight, however, evaded capture. He later stated his company had unsuccessfully attempted to break through Confederate lines to join the Union Army.[2]

Reconstruction and later life

After the end of the war, the Union Army tasked Knight with distributing food to struggling families in the Jones County area. He also led a raid that liberated several children who were still being held in slavery in nearby Smith county.[1] Like many Southern Unionists, he supported the Republican Party. He had returned to his farm in Jasper County, where he cultivated local crops.

In 1870, Knight petitioned the federal government for compensation for several members of the Knight Company, including the ten who had been executed by Lowry in 1864. He provided sworn statements from several individuals attesting to his loyalty to the Union, including a local judge and a state senate candidate.[2] But the federal Court of Claims ruled that "the evidence fails to support the allegation of the petition that the Jones County Scouts were organized for military service in behalf of United States or that they were in sentiment and feeling throughout the war loyal to the Government of the United States."[19]

Knight supported the Reconstruction administration of Republican Governor Adelbert Ames. In 1872, he was appointed as deputy U.S. Marshal for the Southern District. As conflict mounted between white paramilitary insurgents and the Republican Reconstruction government, in 1875, Ames appointed Knight as colonel of the First Infantry Regiment of Jasper County, an otherwise all-black regiment defending residents against insurgent activity. White Democrats regained control of the state government later that year, and forced Ames out of office. Reconstruction ended officially in 1877. Knight withdrew from politics.[1]

By the mid-1870s, Knight had separated from his wife, Serena. He married Rachel, a freedwoman formerly held as a slave by his grandfather.[1] In this period, Knight's grown son, Mat (from his first wife), married Rachel's grown daughter, Fannie, from a previous union. Knight's daughter, Molly, married Rachel's son, Jeff, making three interracial families in the community.[4]: 2 Newton and Rachel Knight had several children before her death in 1889.[1]

Newton Knight died on February 16, 1922, at the age of 92. In spite of a Mississippi law that barred the interment of whites and blacks in the same cemetery,[20] he was buried at his request in what is now called the Knight Family Cemetery, next to Rachel on a hill in Jones County overlooking their farm.[1] Newton's engraved epitaph read, "He lived for others."[21]

In 1964, the great-great-grandchildren of Newton Knight and Rachel, 9-year-old Edgar and 8-year-old Randy Williamson had never attended a day of school because local school authorities, fearing violence and opposition from residents, refused their admittance to a white school and, being 1/16 or 1/32 African American, they were considered as whites and consequently barred from being admitted to a black school.[22]

Legacy

Early accounts of Knight and his followers were published by descendants of him and other local figures of the Civil War years. In 1935, Knight's son, Thomas Jefferson "Tom" Knight, published a book about his father, The Life and Activities of Captain Newton Knight. Tom Knight portrayed his father as a Civil War-era Robin Hood who refused to fight for a cause with which he did not agree. The book notably omits Newton Knight's post-war marriage to Rachel.[4]: 2

A great-niece, Ethel Knight, wrote a 1951 history entitled Echo of the Black Horn: An Authentic Tale of 'The Governor' of the 'Free State of Jones.' She criticized Knight as a traitor to the Confederacy and castigated him for his marriage to a freedwoman, Rachel Knight.[23] Ethel Knight portrayed Newton as a backward, ignorant, murderous traitor. She argued that most members of the Knight Company were not Unionists, but had been manipulated by Knight into joining his cause.[2]

Dr. Rudy H. Leverett wrote The Legend of the Free State of Jones (University of Mississippi Press, 1984, reprinted 2009), the first 20th-century book-length academic study of events in Jones County before and during the Civil War. The great-grandson of Major Amos McLemore, who was allegedly assassinated by Knight,[1] Leverett argues that the Knight Company's actions did not represent most residents of Jones County. He provides evidence that a majority were loyal to the Confederacy, and concludes that Jones County never seceded from the Confederacy.[24] Leverett wrote that, while "few of these people had any real stake in the great economic and political issues that precipitated the war and that most of them opposed the political policy of secession [of the South from the Union], the threat of coercion of the South by the North galvanized the loyalties of Jones Countians to their region and their way of life [The Confederacy]. And for most of them, that loyalty never wavered."[24]

His ancestor McLemore commanded one of eight volunteer companies raised in the county for service in the war.[25] Leverett notes a "Union raiding party entering the county in June of 1863 was captured in part by civilians or the Ellisville 'Home Guard,' and the Union prisoners had to be protected from the local citizens."[25]

Dr. Victoria E. Bynum wrote The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest War (2003), exploring the economic, religious and kinship factors that helped shape the views of Civil War era residents of the Jones County area. Most were not slaveholders; only 12% of the county population in 1860 was black. Bynum also concluded that Jones County had not seceded from the Confederacy. She writes that Newt Knight and two followers contended that they had never left the Union.

Bynum writes,

Newt himself, as well as his 1st Sgt., Jasper J. Collins, and Jasper's son, Loren, all denied the myth of secession during their lifetimes. In separate interviews or publications, these three men made the same point: that it was their belief that Jones County had never left the Union in the first place.[26]

Bynum explored the regional history beyond the War, examining the common-law marriages of Newton Knight and Rachel, a freedwoman, and of two pairs of their grown children, forming three interracial families. She traces their legacy into the twentieth century, including a case that reached the Mississippi Supreme Court.[27]

Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer wrote a popular account, 'The State of Jones', that expands marginally on Leverett's and Bynum's research. The authors emphasize the extent to which Knight and his close allies ended Confederate control of Jones County during the war and continued to express anti-racist, pro-Unionist sympathies during Reconstruction.

In popular culture

James H. Street's 1942 novel, Tap Roots, is very loosely based on the Knight Company's actions. The novel's protagonist, Hoab Dabney, was inspired by Newton Knight.[4]: 2 The book was the basis of the 1948 film, Tap Roots, directed by George Marshall and starring Van Heflin and Susan Hayward.[citation needed] In 2016, the film Free State of Jones, directed by Gary Ross and starring Matthew McConaughey and Gugu Mbatha-Raw, was released.[28] The film closely follows Knight's life.[29]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m James R. Kelly, Jr., "Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine," Mississippi History Now, April 2009. Retrieved: 2 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Victoria Bynum, "Telling and Retelling the Legend of the 'Free State of Jones,'" Guerillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front (University of Arkansas Press, 1999), pp. 17–29.

- ^ The Free State of Jones and The Echo of the Black Horn: Two Sides of the Life and Activities of Captain Newt Knight (2016)[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Victoria Bynum, The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 378

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 43–45

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 73–7

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 38–39, 80–82

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 82–83

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 95–99, 112–15

- ^ Official Records of the War, 1:32, part 3, p. 580

- ^ Official Records of the War, 1:32, part 3, p. 727

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, pp. 2–3, 137–41

- ^ a b Bynum, Victoria (11 March 2016). "An Important Archival Discovery: 1864 Letter describes Free State of Jones". Renegade South. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ^ Rudy H. Leverett, Legend of the Free State of Jones, p. 22

- ^ Official Records of the War, 1:32, part 3, pp. 662–63

- ^ Sally Jenkins, John Stauffer, The State of Jones (2009) p. 5

- ^ Samuel Willard, "A Myth of the Confederacy," The Nation, Vol. 54, No. 1395 (March 1892), p. 227.

- ^ United States Congressional Serial Set, Issue 5156 (Washington, 1907), pp. 111–112. [2]

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 283

- ^ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 307

- ^ Brannock, Jennifer (1964). "Letter documenting the struggle of two children's attempt to attend school". University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved 2019-06-24.

- ^ Knight, Ethel. The Echo of the Black Horn, pp. 69, 261, 321, 327.

- ^ a b Leverett (1984), Legend of the Free State of Jones, p. 64.

- ^ a b Leverett (1984), Legend of the Free State of Jones, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Vikki Bynum, "Did Jones County Secede from the Confederacy?", Renegade South blog, December 23, 2008.

- ^ The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War by Victoria E. Bynum, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, page 186, and Knight v. State (1949) 207 Miss. 564 [42 So.2d 747]

- ^ Pamela McClintock, "Matthew McConaughey's 'Free State of Jones' Goes Up Against 'Independence Day: Resurgence'", The Hollywood Reporter, March 9, 2016.

- ^ Richard Grant, "The True Story of the 'Free State of Jones'", Smithsonian, 2016

Further reading

Books

- Knight, Ethel (1951), Echo of the Black Horn: An authentic tale of "the Governor" of "The Free State of Jones, ASIN B0007EMIXG

- Bynum, Victoria E. (2003), The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-5467-0

- Downing, David C. (2007), A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy. Nashville: Cumberland House. ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9

- Jenkins, Sally; Stauffer, John (2009), The State of Jones, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-385-52593-0

- Bynum, Victoria E. (2010), The Long Shadow of the Civil War: Southern Dissent and Its Legacies, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 231, ISBN 978-1-4696-0987-4

- Marsh, Dorthy Knight (2016), Cotton Fields to Mission Fields: The Anna Knight Story, Morrisville, NC: Lulu Publishing Services, p. 208, ISBN 978-1-4834-6024-6

Articles

- Moulds, Wyatt (2016), The Legend of Newt Knight and the Free State of Jones

- Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones, Smithsonian Associates Civil War Newsletter, Volume 10, Number 3

- The story behind "Free State of Jones", CBS News

- The True Story of the 'Free State of Jones', Smithsonian magazine

- Newton Knight Biography, biography.com

- Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones, Mississippi Historical Society

External links

- Newt Knight Preservation Society

- The Free State of Jones – Literary Works of Victoria Bynum, author of The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War

- Renegade South, blog by Vikki Bynum

- Newton Knight at Find a Grave

- 1829 births

- 1922 deaths

- American Calvinist and Reformed Christians

- Baptists from Mississippi

- Mississippi Republicans

- People from Jones County, Mississippi

- People of Mississippi in the American Civil War

- Southern Unionists in the American Civil War

- United States Marshals

- 19th-century Baptists

- Left-wing populism in the United States

- Left-wing populists