Value-stream mapping

Value-stream mapping, also known as material- and information-flow mapping,[1] is a lean[2]-management method for analyzing the current state and designing a future state for the series of events that take a product or service from the beginning of the specific process until it reaches the customer. A value stream map is a visual[2] tool that displays all critical steps in a specific process and easily quantifies the time and volume taken at each stage. Value stream maps show the flow of both materials and information as they progress through the process.[3]

Whereas a value stream map represents a core business process that adds value to a material product, a value chain diagram shows an overview of all activities within a company.[3] Other business activities may be represented in "value stream diagrams" and/or other kinds of diagram that represent business processes that create and use business data.

Purpose

[edit]The purpose of value-stream mapping is to identify and remove or reduce "waste" in value streams,[2] thereby increasing the efficiency of a given value stream. Waste removal is intended to increase productivity by creating leaner operations which in turn make waste and quality problems easier to identify.[4]

Applications

[edit]Value-stream mapping has supporting methods that are often used in lean environments to analyze and design flows at the system level (across multiple processes).

Although value-stream mapping is often associated with manufacturing, it is also used in logistics, supply chain, service related industries, healthcare,[5][6] software development,[7][8] product development,[9] project management,[2] and administrative and office processes.[10]

Identifying waste

[edit]Types of waste

[edit]Daniel T. Jones (1995) identifies seven commonly accepted types of waste. These terms are updated from Toyota's operating model "The Toyota Way" (Toyota Production System, TPS) original nomenclature (muda):[11]

- Faster-than-necessary pace: creating too much of a good or service that damages production flow, quality, and productivity. Previously referred to as overproduction, and leads to storage and lead time waste.

- Waiting: any time goods are not being transported or worked on.

- Conveyance: the process by which goods are moved around. Previously referred to as transport, and includes double-handling and excessive movement.

- Processing: an overly complex solution for a simple procedure. Previously referred to as inappropriate processing, and includes unsafe production. This typically leads to poor layout and communication, and unnecessary motion.

- Excess stock: an overabundance of inventory which results in greater lead times, increased difficulty identifying problems, and significant storage costs. Previously referred to as unnecessary inventory.

- Unnecessary motion: ergonomic waste that requires employees to use excess energy such as picking up objects, bending, or stretching. Previously referred to as unnecessary movements, and usually avoidable.

- Correction of mistakes: any cost associated with defects or the resources required to correct them.

Waste removal operations

[edit]Yasuhiro Monden (1994) identifies three types of operations:[12]

- Non-value adding operations (NVA): actions that should be eliminated, such as waiting.

- Necessary but non-value adding (NNVA): actions that are wasteful but necessary under current operating procedures.[11]

- Value-adding (VA): conversion or processing of raw materials via manual labor.[11]

NNVA activities may also be referred to as "sustaining non-value adding", i.e. they have to be done, or they are necessary to sustain the business but do not contribute to customer requirements.[13]

For additional views on waste, see Lean manufacturing.

Using the method

[edit]There are two kinds of value stream maps, current state and future state. The current state value stream map is used to determine what the process currently looks like, the future state value stream map focuses on what the process will ideally look like after process improvements have occurred to the value stream.[3]

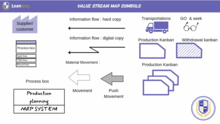

The current state value stream map must be created before the future state map and is created by observing the process and tracking the information and material flow.[14] The value stream map is then created using the following symbols:[15]

In a build-to-the-standard form, Shigeo Shingo[16] suggests that the value-adding steps be drawn across the centre of the map and the non–value-adding steps be represented in vertical lines at right angles to the value stream. Thus, the activities become easily separated into the value stream, which is the focus of one type of attention, and the "waste" steps, another type. He calls the value stream the process and the non-value streams the operations. The thinking here is that the non–value-adding steps are often preparatory or tidying up to the value-adding step and are closely associated with the person or machine/workstation that executes that value-adding step. Therefore, each vertical line is the "story" of a person or workstation whilst the horizontal line represents the "story" of the product being created.

Value-stream mapping is a recognised method used as part of Lean Six Sigma methodologies.[17]

Value-stream mapping analyzes both material (artifact) and information flow.[18] The following two resources exemplify the use of VSM in the context of software process improvement in industrial settings:

- "Artifact analysis": analysis of software artifacts like requirements, use case, change request or defect report through the development process[19]

- "Information flow analysis": analysis of information flows in the development process[20]

Associated analysis methods

[edit]Hines and Rich (1997) defined seven value-stream mapping tools.[21] These are:

- Process activity mapping: the initial step of constructing a map which consists of a study of process flows, waste identification, and business process re-engineering.

- Supply chain response matrix: identifying critical bottlenecks for processes in a simple diagram.

- Production variety funnel: helps draw connections to other industries that may have solutions to existing problems.

- Forrester effect mapping: line graphs showing the customer demand and production, allowing visualisation of supply and demand and potential delays.

- Quality filter mapping: locates product and service defects in the supply chain.

- Decision point analysis: determines inflection points for push-and-pull demand in the supply chain.[22]

- Physical structure mapping: combined model that overviews supply chain from an industry level.[11]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Manos, Tony (June 2006). "Value Stream Mapping—an Introduction". Quality Progress. American Society for Quality. p. 64 – via University of Washington.

- ^ a b c d Project Management Institute 2021, §4.6.6 Focus on Value.

- ^ a b c Rother, Mike; Shook, John (1999). Learning to See: value-stream mapping to create value and eliminate muda. Brookline, Massachusetts: Lean Enterprise Institute. ISBN 0-9667843-0-8.

- ^ Depository, Book. "34 for Quality : John Bicheno : 9780951382943". www.bookdepository.com. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ Graban, Mark (2011). Lean Hospitals: Improving Quality, Patient Safety, and Employee Engagement. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439870433.

- ^ Graban, Mark; Swartz, Joseph (2011). Healthcare Kaizen: Engaging Front-Line Staff in Sustainable Continuous Improvements. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439872963.

- ^ Plenert, Gerhard (2011). Lean Management Principles for Information Technology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 9781420078602.

- ^ Bell, Steven; Orzen, Michael (2010-09-14). Lean IT: Enabling and Sustaining Your Lean Transformation. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439817568.

- ^ Mascitelli, Ronald (2011). Mastering lean product development: a practical, event-driven process for maximizing speed, profits and quality. Northridge, California: Technology Perspectives. ISBN 9780966269741.

- ^ Keyte, Beau; Locher, Drew (2004). The Complete Lean Enterprise: Value Stream Mapping for Administrative and Office Processes. New York: Productivity Press. ISBN 9781563273018.

- ^ a b c d Hines, Peter; Rich, Nick (1997-01-01). The seven value stream mapping tools. Vol. 17.

- ^ Toyota Production System - An Integrated Approach to Just-In-Time | Y. Monden | Springer.

- ^ Cain, M., Business Process Improvement: the Hambleton Story, accessed 13 August 2020

- ^ Ali N.B., Operationalization of lean thinking through value-stream mapping with simulation and FLOW [dissertation]. Karlskrona: Department of Software Engineering, Blekinge Institute of Technology; 2015.

- ^ "Value Stream Mapping symbols : From Clarity to Chaos The Unintended consequences". Leandemy. 2023-09-08. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ Shingo, Shigeo (1985). A Revolution in Manufacturing: The SMED System. Stamford, Connecticut: Productivity Press. pp. 5. ISBN 0915299097.

- ^ "Value Stream Mapping" Article Source: http://www.isixsigma.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&layout=category&task=category&id=90&Itemid=222#

- ^ Rother, Mike, and John Shook. Learning to see: value stream mapping to add value and eliminate muda. Lean Enterprise Institute, 2003.

- ^ Ali NB, Petersen K, Breno Bernard Nicolau de França. Evaluation of simulation-assisted value-stream mapping for software product development: Two industrial cases. Information and Software Technology. 2015;68:45.

- ^ Ali NB, Petersen K, Schneider K. FLOW-assisted value-stream mapping in the early phases of large-scale software development. Journal of Systems and Software. 2016;111:213-27.

- ^ Rich, Nick; Esain, Ann; Bateman, Nicola (1997). Lean Evolution: Lessons from the Workplace. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Hoekstra, Sjoerd; Romme, Jac (1992). Integral Logistic Structures: Developing Customer-oriented Goods Flow. Industrial Press Inc. ISBN 9780831130374.

References

[edit]- Project Management Institute (2021). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide). Project Management Institute (7th ed.). Newtown Square, PA. ISBN 978-1-62825-664-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit] Media related to Value stream mapping at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Value stream mapping at Wikimedia Commons- Value-stream mapping – Lexicon term at the Lean Enterprise Institute website