George Washington Masonic National Memorial

| George Washington Masonic National Memorial | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Museum, observation |

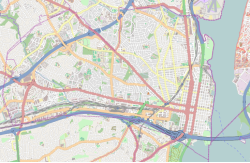

| Location | 101 Callahan Drive, Alexandria, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 38°48′27″N 77°03′58″W / 38.80748°N 77.06598°W |

| Construction started | June 5, 1922[1] |

| Completed | 1932 |

| Opening | May 12, 1932[2] |

| Cost | $6 million[3] |

| Owner | George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association |

| Height | |

| Roof | 333 ft (101 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 9 |

| Lifts/elevators | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Harvey Wiley Corbett of Helmle & Corbett |

| Structural engineer | Osgood & Osgood, Grand Rapids, Michigan |

| Main contractor | Percy Cranford Co., Washington, D.C. |

George Washington Masonic National Memorial | |

| Coordinates | 38°48′27″N 77°03′58″W / 38.80748°N 77.06598°W |

| NRHP reference No. | 15000622 |

| Designated NHL | July 21, 2015[4] |

| Part of a series on |

| Freemasonry |

|---|

|

The George Washington Masonic National Memorial is a Masonic building and memorial located in Alexandria, Virginia, outside Washington, D.C. It is dedicated to the memory of George Washington, first president of the United States and charter Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 (now Alexandria-Washington Lodge, No. 22). The tower is fashioned after the ancient Lighthouse of Ostia in Ostia Antica (or Rome).[5][6][7] The 333-foot (101 m)[8][9] tall memorial sits atop Shooter's Hill[10][11][12] (also known as Shuter's Hill)[13] at 101 Callahan Drive. Construction began in 1922,[1] the building was dedicated in 1932,[2] and the interior finally completed in 1970.[14] In July 2015,[4] it was designated a National Historic Landmark[15] for its architecture, and as one of the largest-scale private memorials to honor Washington.[16]

The memorial is served by the King Street–Old Town Metro station on the Blue and Yellow Lines of the Washington Metro.[10] The station is located about four blocks from the memorial.

Early memorial efforts and Washington Memorial Park

[edit]The idea to construct a Masonic memorial for George Washington was first proposed in 1852 by the Washington area's "mother lodge," Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 (located in Fredericksburg, Virginia).[17] Funds were sought from Grand Lodges (state-level Masonic organizations) throughout the United States to construct a memorial Masonic Temple with a large statue in the vestibule.[18] Enough funds were raised to commission a life-size bronze statue of Washington in full Masonic regalia from the famous sculptor, Hiram Powers who was living in Rome, Italy.[19] The statue reached Alexandria in early 1861, just before the outbreak of the American Civil War.[19] It remained on display in Alexandria until the summer of 1863, when it was moved to Richmond, Virginia.[19] The statue was destroyed in the fire which occurred as Richmond surrendered to the Army of the Potomac on April 3, 1865.[19]

Plans for a Masonic memorial moved forward again in 1909 after work on a competing memorial began. The proposed site for the new memorial was Shooter's Hill, which at one time had been seriously considered by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson as the site of the United States Capitol building.[20][21] On May 8, 1900, citizens of Alexandria formed the "Washington Monument Association of Alexandria" (WMAA), a nonprofit organization whose mission was to build a memorial to George Washington in the city of Alexandria. Little was accomplished in the organization's first few years of life, but in February 1908 the WMAA purchased an option to buy a 50-acre (20 ha) tract of land on and around Shooter's Hill and the nearby Alexandria Golf Course.[22] Most of the land immediately on either side of King Street was subdivided into housing tracts and sold, with 25 acres (10 ha) on top of Shooter's Hill reserved for a memorial.[23] The sale of the housing subdivisions paid for the purchase of the entire tract, with enough left over to provide for construction of a memorial.[23]

Within a month of the purchase of Shooter's Hill, the WMAA decided to build a park rather than a memorial.[24] About 15 acres (6.1 ha) were set aside for the George Washington Memorial Park, while another 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) were set aside for a small memorial within the park.[24] The new subdivision, named Fort Ellsworth (after an American Civil War fort which used to occupy Shooter's Hill), was platted in November 1908, and public streets laid out.[25][26] The park was ready for dedication on April 30, 1909—the 120th anniversary of the inauguration of Washington as president. Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22 (George Washington's Masonic lodge, as well as the lodge he led as a Worshipful Master) was asked to preside over its dedication.[27] President William Howard Taft, Vice President James S. Sherman, Speaker of the House Joseph Gurney Cannon, Virginia Governor Claude A. Swanson, Virginia Lieutenant Governor J. Taylor Ellyson, the Board of Commissioners of the District of Columbia, Baltimore Mayor J. Barry Mahool, and numerous other dignitaries attended the dedication ceremony.[28] (Shooter's Hill was incorporated into the city of Alexandria on April 1, 1914.)[29]

Formation of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association

[edit]There were several reasons why Masonic bodies finally began to build a memorial. The construction of George Washington Memorial Park sparked renewed Masonic interest in building their own memorial. But another reason was the safety of items owned or used by George Washington ("Washingtoniana") and which were now owned by the Alexandria-Washington lodge. The lodge had suffered several fires over the previous century, and a number of these historic items were destroyed.[14][30] Constructing a fire resistive building which would more safely house these important items was a major factor in pushing the Masonic memorial forward.[14][30][31]

In late 1907 or early 1908, Alexandria Commissioner of Revenue Charles H. Callahan (the deputy master of Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22) proposed to his fellow Masons that, at last, a memorial to George Washington should be built.[2][32][33] Callahan proposed the construction of a $10,000 memorial temple.[34] In early 1908, the Alexandria-Washington Lodge formed a "local memorial temple committee" to research the costs and obstacles involved in building a memorial temple.[2] The committee passed a resolution asking Joseph Eggleston, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Virginia, to approve the creation of a memorial temple and to assist in creating a national memorial association in which all Masons and Masonic organizations could participate.[2]

On May 7, 1909, the Grand Lodge of Virginia called upon all grand lodges in the United States to meet in Alexandria on February 22, 1910, to discuss plans for organizing a George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association whose purpose would be to construct a memorial temple.[34][35] President Taft, Representative Champ Clark, Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson, and Virginia Governor William Hodges Mann all spoke at the February 22 meeting.[36] The George Washington Masonic National Memorial Association (GWMNMA) was formed at this meeting, and plans were adopted to raise $500,000 to go toward the cost of construction and another $500,000 for an endowment and maintenance fund.[37] Thomas J. Shryock, Grand Master of Maryland (and a former treasurer of Maryland and brigadier general in the Maryland National Guard), was elected president of the GWMNMA.[38]

At this point, the GWMNMA only planned to construct a Masonic temple, not a giant memorial.[37] One floor was to be set aside for use by Masonic lodges, and one or more fire resistive, secure rooms in the temple were to be used for the display of Washingtoniana and historical documents owned by the Alexandria-Washington Lodge.[37] By February 1911, the GWMNMA had ruled out all locations except Alexandria as the site for its memorial temple, and fund-raising activities were being planned.[39] A more formal association structure was also adopted at this time.[40] But except for fund-raising activities, little was done in the association's first five years of activity.

Site selection

[edit]Nearly everyone involved in the project in its early years agreed the memorial temple had to be built in Alexandria due to Washington's extensive ties to that city.[2] George Washington Memorial Park seemed a good location, but this park was still privately owned by the WMAA.[41] In September 1915, the Alexandria-Washington Lodge offered to buy several lots on top of Shooter's Hill for $1,000.[41] At about the same time, the city of Alexandria discussed whether it should ask the WMAA to turn over the remainder of George Washington Memorial Park to the city.[41] The lodge suggested that 28 acres (11 ha) of the eastern slope of George Washington Memorial Park be retained as a public park, while the rest of the tract could be used for any purposes the city wanted.[41] This plan was not acted on. By December 1915, the city had purchased all of Shooter's Hill and George Washington Memorial Park from the WMAA except for a 2-acre (0.81 ha) area (lots 29 through 38, inclusive, of block 5)[42] on the north slope of the hill.[29] In October or December 1915 (sources disagree on the date), the Alexandria-Washington Lodge purchased the north slope of Shooter's Hill (an area about 400 by 200 feet (122 by 61 m)) for $1,000.[43][44][45] Under the terms of the conveyance of the deed, the Masons were required to build a memorial temple (costing no less than $100,000) to George Washington at the top of the hill within 10 years or they would be forced to turn over the land to the city of Alexandria.[29]

With land secured, the Masons began making plans to build a memorial. In 1917, the Alexandria-Washington Lodge reported that the intent remained to construct a $500,000 building to house the Washingtoniana (valued at $2 million) which the lodge held.[44] The GWMNMA had raised $5,000, and another $20,000 in donations was anticipated.[43][44] GWMNMA President Thomas J. Shryock died on February 3, 1918, and Louis Arthur Watres (former Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania and a former Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania) was elected president as his successor.[2] At its annual meeting just two weeks later, the association approved the employment of an architect to begin developing plans for the memorial. Watres departed for New York City to interview architects. On the train, he met Harvey Wiley Corbett of the New York City firm of Helmle & Corbett (and coincidentally a Freemason).[46] The GWMNMA selected Corbett to be the chief architect.[47][48][49][9]

By February 1922, the GWMNMA had radically revised its plans for the memorial. Now the association planned a building which would cost $1.5 million, with another $400,000 set aside for landscaping the grounds and $500,000 as an endowment for perpetually maintaining the memorial.[50][51] The directors of the GWMNMA also approved a new charter for the organization, inspected the building site, and approved blueprints for the building.[51] The state of Virginia approved the revised charter for the GWMNMA on March 16, 1922.[52]

Early designs

[edit]

Corbett planned a three-story memorial temple topped by a three-story tower. The first three floors (which constituted the temple and the base of the tower) would be built in the Neoclassical style, while the tower would be a variation on the setbacks popular in Modern architecture.[48] The structure was to be built entirely of masonry, with almost no metal used in its construction (except for reinforcing rods in the concrete).[32][53] The rationale for this decision was that a building constructed purely of stone would be the most permanent structure possible.[32][53] The firm of Osgood & Osgood of Grand Rapids, Michigan, was the consulting engineer.[49][54][55] Daniel E. Moran (of the firm Moran, Maurice & Proctor of New York) designed the building's foundation; Gunvald Aus was the structural engineer; the firm of Clarke, McMullen & Riley (of New York) was the mechanical engineer; and Carl Rust Parker of Olmsted Brothers was the landscape architect.[56] The general contractor was the Percy Cranford Co., but the actual masonry work was done by the Samuel Miller Co. (both companies were located in Washington, D.C.).[56]

Corbett's initial design was for a memorial about 200 feet (61 m) high.[57] Corbett drew his inspiration from the restoration of the lighthouse at the port of Ostia Antica near Rome.[8][58] The first floor was occupied by a main hall with a colonnade on either side and clerestory windows, at the back of which a large statue of Washington would reside.[57] Historic murals would be painted on the walls.[57] To the right and left of the main hall would be large meeting rooms (one for the use of the Alexandria-Washington Lodge and one for use by other Masonic bodies).[57] To the left of the main hall there would also be a small room which would contain a replica of the original Masonic lodge room in which Washington himself had presided.[59]

Additional details and apparent design changes were revealed in July 1922. Although the building was still just 200 feet (61 m) in height, the press now reported that the building would be built specifically in the Greek and Romanesque Revival styles and be constructed of white marble and white concrete.[60][61] The atrium of the building (as the first floor main hall was now called) was now slated to contain space along the walls which could be used by Grand Lodges to memorialize their prominent members, while the rooms around the atrium would be dedicated to the various Masonic "appendant bodies" (jurisdictional bodies, social groups, youth and women's organizations, etc.).[60] The plan called for the second floor to be used as an art gallery as well as a museum, and for the museum to not only honor Washington but also other famous Masons from Virginia.[60] The memorial was still intended to house Washingtoniana and contain a replica of the original Alexandria-Washington Lodge's meeting room.[60]

A major revision to the memorial plans was made in February 1923. The GWMNMA approved constructing the building entirely of granite (rather than marble and concrete), a change which increased the cost of the structure to $3 million.[62] Including landscaping and the endowment, the total cost of the structure had risen to $4 million.[63]

These plans were revised and elaborated on again by April 1923. Now the memorial was to stand 330 feet (100 m) high.[54] The atrium on the first floor was specified to be 45 feet (14 m) wide by 80 feet (24 m) deep.[54] With the clerestory windows, this hall would be 60 feet (18 m) in height.[54] Meeting rooms would still surround the atrium.[54] The second story, now 45 by 60 feet (14 by 18 m) in size with a high ceiling and extensive windows (to let in large amounts of natural light), was still slated to house the Washington museum.[54] The purpose of the third floor was not yet agreed upon.[54] The tower above the third floor now contained an observation deck forming a seventh and ultimate floor at the top of the tower.[54] The new plans specified that terraces would lead from the front steps of the memorial down to the street below.[54] The cost, however, was still budgeted for $4 million.[49]

The final major change in the memorial came in early 1924. The height of the tower had been decreased at some point to 280 feet (85 m).[61] But in February 1924, architect Corbett raised the tower's height back to 330 feet (100 m).[61]

Construction of the building

[edit]Building the foundation

[edit]Given the size and weight of the memorial, even in its early design stages, a solid foundation for the structure was critical. An initial test borehole into Shooter's Hill (which reached a depth of 200 feet (61 m)) found no bedrock, leading to concerns that the site might not be a suitable location for the building.[30] Daniel E. Moran, the foundation engineer, further investigated the earth beneath the building.[64] Moran drilled 125 feet (38 m) below the lowest point of the foundation and found gravel, hard clay, and sand.[30][64] Soil experts in New York City and with the United States Geological Survey analyzed the soil and provided a guarantee (backed up by a bond) that no settling of the building would occur due to soil conditions.[30][64]

Ground for the memorial was broken at noon on June 5, 1922.[1] Louis Watres, president of the association, and Charles H. Callahan, vice president, broke ground in a driving rain.[1] The shovel and pick used to break ground, as well as four small stones from the first two spades of earth turned, were preserved by the Alexandria-Washington Lodge.[1] Excavation of the memorial's foundation began a few days later, with Cranford Paving Co. of Washington, D.C., doing the work.[1][56] The foundation was roughly hemispherical to provide the greatest stability,[30] and 25 feet (7.6 m) of the top of hill removed (lowering the elevation to just 108 feet (33 m)) in order to accommodate the 177-foot (54 m) wide by 195-foot (59 m) long foundation.[65] To ensure that the clay remained damp and did not dry out, which would cause the building to settle, a concrete pad 168 by 248 feet (51 by 76 m) was laid on top of the clay. This pad was 9 feet (2.7 m) deep in the center but only 6.5 feet (2.0 m) deep on the edges, and consisted of 9,000 cubic yards (6,900 m3) of concrete and 720 short tons (650 t) of reinforcing steel rods. The pad was allowed to set for several months before work began on the foundation itself.[66] The basement of the building was as large as the first two floors combined and was intended to house the structure's mechanical plant.[67] Although steam shovels were used to excavate the foundation, the earth was carried away by mule-drawn wagons.[30][68] A wide road was constructed to the top of Shooter's Hill to permit the transport of earth off the site and construction materials to the hilltop.[68]

By July 1922, the GWMNMA had received $700,000 in donations and another $900,000 in pledges.[60] Some time in the spring of 1922, the GWMNMA also obtained title to the 32-acre (13 ha) tract encompassing the rest of Shooter's Hill.[60] About 22 acres (8.9 ha) of the tract, valued at $1 million, was purchased from the city of Alexandria at almost no cost (essentially making it a gift from the city).[2][60] The total size of the tract owned by the Masons was now 36 acres (15 ha).[2]

By January 1923 the foundation was almost completed and the granite walls for the first floor were rising. Work proceeded very rapidly through June.[69] By February 1923, $1 million had been spent on constructing the foundation and walls and on landscaping.[62] Topsoil for the landscaping came from the Earl Strong Co. of Alexandria, the grass seed from O.M. Scotts and Sons of Ohio, and other trees, shrubs and landscaping products from C.F. Armiger of Washington, D.C.[56] Revenues easily exceeded these expenditures, as $1.8 million had been received in donations and pledges.[63] The same month, the GWMNMA expanded its board of directors from nine to 12.[63] By April 1923, the foundation had been fully excavated and the foundation walls constructed.[70] The Washington Post reported that the concrete foundation was the largest ever cast in a single piece.[56][71] The foundation (of articulate girder design) was 39,000 square feet (3,600 m2) in size, 4.5 to 9 feet (1.4 to 2.7 m) thick, and contained 9,000 cubic yards (6,900 m3) of concrete.[56][67] Plows pulled by mules had reshaped the side of the hill into its terraced form,[68] and most of the landscaping was now done.[70] Total cash donations received by April 1923 totaled more than $1 million.[70] Concrete for the first floor was poured in June 1923 and once it had set, the eight green 20 short tons (18 t) granite marble columns in the atrium were set in place. Each green marble column was 40.5 feet (12.3 m) high and 2.5 feet (0.76 m) in diameter when finished.[72] To prevent the columns from twisting or slipping, a mortise and tenon was used. A mortise approximately 3 feet (0.91 m) deep was created in the floor and a tenon carved on the bottom of the column base. A small amount of mortar mixed with small flat discs of metal was used to help fix the tenon into the mortise. Between the base and the first drum (or section of the column), between the drums and between the top drum and the capital were placed wedge-shaped thin sheets of lead to inhibit slippage.[73] By October 15, the first floor and granite outer walls were complete.[69]

Laying of the cornerstone

[edit]

Laying of the memorial's cornerstone occurred on November 1, 1923. Planners had initially proposed that cornerstone be laid on November 4, 1923—the 170th anniversary of George Washington's initiation into Freemasonry.[30] But because November 4 fell on a Sunday in 1923, the ceremony was scheduled for November 1.[30] The ceremony almost did not occur. A short time before the event, contractors discovered that the cornerstone for the memorial had been cut too small.[30] A new cornerstone was quickly fashioned and completed just in time.[30] Alexandria Mayor William Allen Smoot declared a holiday, and all businesses closed except for banks and the U.S. post office.[74] The United States Navy light cruiser USS Richmond and a U.S. Navy destroyer anchored at the Alexandria torpedo factory as part of the festivities.[75] Trains ran every three minutes into the city of Alexandria in order to accommodate the crowds.[74]

An estimated 14,000 Masons, dignitaries, United States armed forces personnel, police, and others marched in a parade from the Alexandria waterfront to Shooter's Hill to kick off the event.[74] During the parade, four United States Army Air Corps planes circled overhead.[75] Among the dignitaries present at the 1:00 p.m. cornerstone-laying event were President Calvin Coolidge, now-Chief Justice of the United States William Howard Taft, Virginia Governor Elbert Lee Trinkle, and Alexandria Mayor Smoot.[74][76][77] Charles H. Callahan was master of ceremonies,[77] and the Rt. Rev. James Edward Freeman, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, provided the invocation and benediction.[74][77] President Coolidge laid the cornerstone using the same trowel Washington used on September 18, 1793, to lay the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol building (the trowel was owned by the Alexandria-Washington Lodge).[76] Loudspeakers were used to broadcast the speeches of President Coolidge and the other speakers to the crowd, and a temporary radio station (operated by radio station WCAP) was set up on Shooter's Hill to broadcast the proceedings nationwide.[74][75] (Both the loudspeakers and temporary radio station were the same which President Warren G. Harding had used during the laying of the cornerstone for the Lincoln Memorial.)[75]

Every U.S. state deposited an item into the cornerstone.[74] Other items deposited in the cornerstone were an American flag; a bronze medal celebrating the inauguration of Warren G. Harding; a bronze plaque containing the names of the architects, consulting architects, landscape architects, engineers, and contractors working on the memorial; a Christian Bible; a lambskin apron; a copy of William Joseph Williams' 1794 portrait of George Washington in Masonic regalia; several books and pamphlets concerning the life of Washington and the history of Freemasonry in America; and the names of the board of directors and officers of the GWMNMA.[74] Beneath the cornerstone was another container, which held several dimes, copies of the Constitution, copies of the Declaration of Independence, books, and other items.[68]

Construction milestones

[edit]Construction proceeded slowly after the cornerstone was laid. This was because construction stopped every winter to ensure that the memorial remained free of moisture, frost damage, and the effects of cooling (to improve the fit between stones).[61][72][78][79] The Helmle & Corbett architectural firm did an extensive study of stone buildings in Europe, and determined that working during good weather was the best way to construct a durable building.[79] During 1923, the GWMNMA raised another $500,000 in cash donations, which brought the total received to $2 million.[61] The granite for the memorial came from quarries in New Hampshire,[78] and was provided by the Maine & New Hampshire Granite Corp.[56] Some of these blocks were as much as 20 feet (6.1 m) long.[80]

By the time of the GWMNMA's annual meeting in February 1924, construction on the first floor was almost complete.[61] The first five terraces above the street (the "lower terrace") were built using Potomac bluestone for the walls, while the walks were graveled. The topmost sixth terrace (the "upper terrace", which encircled the building and its main entrance) was constructed with Conway Pink Granite for a base. The base was 13.875 feet (4.229 m) high and 3.33 feet (1.01 m) thick. The upper portion of this wall was concrete. More than 2,200 cubic yards (1,700 m3) of concrete and 60 short tons (54 t) of steel reinforcing bars were used in this part of the wall.[81][82] The GWMNMA believed that the second floor would be finished by the end of the construction season in the fall of 1924,[61] and that the entire structure would be done by late 1927 or early 1928.[78] The association also decided that a statue of Washington should be placed in the memorial atrium, and that this statue should be a marble copy of Jean-Antoine Houdon's 1788 statue of George Washington (which stood in the rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond).[61] In May 1924, the GWMNMA resodded the terrace and spent $6,000 on a new gateway and entrance to the memorial at the foot of Shooter's Hill.[78]

The 1924 construction year ended in December with the installation of eight green marble columns (each weighing 11 to 18 short tons (10.0 to 16.3 t)) in the first floor atrium.[32] Each column was 18 feet (5.5 m) high and 4.5 feet (1.4 m) in diameter,[83] and arrived at Alexandria's Union Station by train from Redstone, New Hampshire.[68] One columnar section was damaged, and given to the Ladies Auxiliary of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). The VFW turned it into a memorial to American war dead, and erected it in front of Alexandria's Union Station.[83] In December 1924, it was estimated that the building would be complete in three to six years.[32]

Work on the building slowed in 1925 due to the difficult nature of completing the roof and raising the tower.[72] About 5,500 cubic feet (160 m3) of pink Conway granite (also quarried near Redstone) was received in May 1925 and used to build the memorial hall on the second floor.[72] The walls of the hall were already 32 feet (9.8 m) high, and about 14 feet (4.3 m) of granite needed to be raised on the northeast and south sides of the hall to complete them.[72] (They were 50 feet (15 m) when finished in December 1925.)[72] Sixteen columns of St. Genevieve marble, quarried in Missouri, were procured and placed around the perimeter of the second floor auditorium to help support the auditorium roof.[72] Each column was 18.5 feet (5.6 m) high and 2.3 feet (0.70 m) in diameter,[72] and weighed 56 short tons (51 t).[84] Once the columns were in place, a jack arch was constructed above them. The arch had two cross-members (each consisting of five stones weighing a total of 70 short tons (64 t)) supported by four 3 inches (7.6 cm) wide, 50 feet (15 m) long steel rods placed in shallow grooves on the underside.[85] The GWMNMA anticipated spending $595,000 in construction funds in 1925,[72] and raised another $500,000 in cash donations.[53]

In 1926, the GWMNMA appropriated another $500,000 to continue construction on the memorial.[86] The first event held in the memorial was the February 22, 1926, GWMNMA annual meeting.[53] The group reported that $2 million in cash donations had been received thus far, and $1.8 million expended.[53] Eight pink Conway granite columns—each 40 feet (12 m) high and weighing 68 short tons (62 t)[64][79]—for the portico were raised into position in October 1926, nearly completing this portion of the structure.[87] Also nearing completion was a massive bas-relief sculpture of Washington's head in profile, designed by sculptor Gail Sherman Corbett (wife of architect Harvey W. Corbett).[56][88][89] G. Fred Coles, who helped execute the statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, did the carving of the sculpture on-site in the summer of 1927 from Corbett's maquette.[89]

At the group's February 1927 meeting, the GWMNMA officers reported raising another $125,000 in cash donations.[90] Six months later, the roof over the first three floors was put in place. The concrete roof was designed by Gunvald Aus, who also designed the Woolworth Building in New York City.[64] Pouring of the concrete roof began on August 22, 1927,[64] and was completed on August 30.[79] Steel for the roof was provided by Concrete Steel Co. of Washington, D.C.[56] The Vulcanite Portland Cement Co. of Philadelphia provided the cement,[56] and Cranford Construction Co. poured the roof.[79] A total of 71 short tons (64 t) of steel reinforcing rods were used in the roof, which contained 953 cubic yards (729 m3) of concrete.[79] The roof was 74.75 feet (22.78 m) wide and 110 feet (34 m) long—reportedly the largest concrete roof in the world at the time.[64][71][79] The roof was supported by four steel-reinforced concrete beams, each beam 72 feet (22 m) long and 14.5 feet (4.4 m) deep.[64][79] Each beam varied from 1 to 5 feet (0.30 to 1.52 m) in thickness, contained 7.5 short tons (6.8 t) of steel reinforcing rods, and weighed 98 short tons (89 t)).[64][79] The beams were supported at the front of the building by four of the pink Conway granite columns.[64][79] At the four corners of the roof were concrete piers, each 9 square feet (0.84 m2) in size.[64][79] Spandrel beams between the columns—6.3 feet (1.9 m) wide at the bottom, 9 feet (2.7 m) wide at the top, and 24 feet (7.3 m) deep—also supported the roof.[64] The roof was waterproofed, sealed, and covered with copper sheeting by the New York Roofing Co. and the Ehret-Warren Co.[56][91] In August 1927, it was believed the building would be finished in another three to five years.[79]

At its February 1928 annual meeting, the GWMNMA agreed to spend another $500,000 in the coming year on construction costs.[92][93] The association also agreed to increase the endowment fund to $1.5 million, for a total cost of building, grounds, and endowment of $5 million.[92][93] At this time, it was estimated that the building could be completed if another $500,000 was raised in 1929.[92][93] The Grand Lodge of the state of Virginia announced at the meeting that it had agreed to fund the construction of bronze doors for the memorial at a cost of $10,000.[67][93] At the close of the meeting, the GWMNMA established a formal dedication date of 1932 for the memorial.[94]

In February 1929, the GWMNMA learned that $400,000 in cash donations were received in 1928.[95] When work on the structure began again in March 1929, the terrace and lawns were resodded.[71] The first Masonic degrees were conferred in the unfinished memorial in mid-October 1929.[96] The first Blue Lodge meeting to be held at the memorial occurred on November 14, 1929.[97] With so many skilled workers unemployed due to the Great Depression, the association was able to hire more men at lower wages than before. By February 1930, the tower section had risen to 190 feet (58 m) above elevation, 50 feet (15 m) more than the construction schedule anticipated.[98] At the GWMNMA annual meeting, the association voted to establish a $1 million endowment fund to maintain the memorial after it was completed.[99] In 1930, the association spent $225,000 on the memorial.[100] That same year, GWMNMA President Watres donated a large Celesta-like set of chimes for the memorial's tower.[67][101] The tower was completed, and floors for the eighth, ninth, and tenth levels installed.[102]

Work on the exterior of the memorial ended on February 8, 1931.[103] The Grand Chapter of Virginia of Royal Arch Masonry donated the aluminum double-keystone symbol and light at the top of the building.[67][100] The fixture, the largest of its kind in the world at the time, was in place by February 1929 but not yet illuminated (as exterior lighting systems were still being installed).[100] The $17,000 light fixture is 19 feet (5.8 m) high, made of aluminum, and has its own independent power supply. Claude Haynes, a steelworker employed on the memorial since 1923 and a member of Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22, completed the light by installing the aluminum sheeting on it on February 8.[103] Construction of decorative items, flooring, landscape drainage, marble walls, and plumbing continued throughout 1931 and was expected to be complete by February 1932.[100] Work on the outbuilding housing the memorial's boiler room began in late March 1931.[104] The brick building was constructed by the Temple B. Greenstreet Co. of Washington, D.C., and the brick smokestacks built by the Alphonse Custodis Co. of New York.[56] A steam tunnel 8 by 8 feet (2.4 by 2.4 m) square and 600 feet (180 m) long carried heat to the building.[105] The outbuilding's two low-pressure boilers and the memorial's interior radiators were supplied and installed by the American Radiator Co.[56] Interior heating and ventilation units and ductwork were provided by the B.F. Sturtevant Co., Benjamin F. Shore Co., and Buffalo Forge Co.[56] Modern thermostats provided by Johnson Service Co. were used to control the heating and cooling.[56] The furnaces used heating oil for fuel, and were installed by the Automatic Heating Corporation of Washington, D.C.[56][106]

Dedication

[edit]The George Washington Masonic National Memorial was dedicated on May 12, 1932. Planners had hoped for a dedication date of February 22, 1932—the 200th anniversary of Washington's birth.[100] But the structure was not ready in time, as many of the interior details had not yet been agreed on or installed,[56] electrical and plumbing work had not yet reached the third floor, and the George Washington National Bicentennial Commission had already scheduled numerous programs for February.[105] Initially, May 13—the 325th anniversary of the founding of the English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia—was chosen as the date for the dedication. But since the number 13 was considered unlucky, May 12 was chosen instead.[107]

Even with an extra two months, the contractors still rushed to finish the building.[108] The huge granite steps leading up to the main entrance were not in place (and would not be until 1940).[109] Among the rooms being prepared at the last minute was the 1,000-seat circular auditorium at the rear of the second floor.[108] Workers laid a cement floor for the auditorium (although this would later be replaced with marble).[108] The marble wall material in the auditorium came from the Hilgartner Marble Co. of Baltimore, while the seating and woodwork came from the American Seating Co. of Grand Rapids.[56][108] The fan-shaped ceiling and the frieze in the auditorium were designed by Louis Ludwig of Washington, D.C., while the installation of the ceiling and the frieze was done by the A.W. Lee Co. of Washington.[56] Contractors were also busy installing sashes, windows and ventilation grillwork throughout the building, and laying a cement floor in the memorial hall on the second floor.[108] Bronze was used for the sashes, doors, doorjambs and other exterior work where connection to the granite was required, and these items were installed by the William H. Jackson Co. of New York.[56] The interior and exterior ironwork was supplied by the Alexandria Iron Works and the Washington Stair and Ornamental Iron Co.[56] Other than the auditorium, no attempt was made to complete the first floor, the lodge rooms on the second floor or any of the tower rooms in time for the dedication.[108]

The memorial had been constructed without incurring any debt. From the start of the project, the Masonic bodies involved in the memorial's construction resolved not to sign any contract or begin any work until the money for such efforts was in hand.[110] At the time of the dedication, not a single bond had been sold or loan sought to fund the building's construction.[110]

A number of special events marked the dedication ceremony. More than 100 special trains carried an estimated 150,000 spectators into Alexandria.[2] Many attendees slept in railway sleeping cars (which remained parked in the city's rail yards) because hotel accommodations were lacking.[2] The U.S. Navy sailed the historic wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate USS Constitution to Alexandria for the dedication.[111] Three United States Coast Guard cutters and a U.S. Navy submarine also anchored in the Potomac River for the ceremony.[112] The United States Post Office Department established a special temporary ceremonial post office at the site of the memorial to postmark letters and postcards with the memorial's name and location and the date of the dedication ceremony.[113] (More than 200,000 letters were postmarked at the ceremonial station that day.)[114] The United States House of Representatives adjourned because most House members were attending the dedication event.[115] Most members of the United States Senate also went to the dedication, as did a number of foreign ambassadors.[2]

A continuous heavy rain dampened the May 12 festivities.[116] Only about 20,000 people (rather than the anticipated 150,000) lined Alexandria's streets to view the parade.[116] Originally estimated to incorporate 20,000 participants, only 15,000 marched in the parade through Alexandria to the memorial prior to the dedication ceremony.[2][112][116] More than 5,000 U.S. military personnel and 3,000 Knights Templar (the third part of the York Rite system of Masonic degrees) marched in the procession.[2][112] The contingents took more than two hours to pass the reviewing stand.[116] Representatives from every branch of Freemasonry in the U.S. attended and many representatives from overseas Masonic lodges were also present.[2] President Hoover and nearly his entire Cabinet attended the dedication.[2][34] When the President and his party arrived at the memorial site, the Constitution, the three Coast Guard ships and a battery of the 16th Field Artillery fired a 21-gun salute.[2][112][116]

Due to the heavy rain, the ceremony was moved from the portico of the memorial to the newly completed auditorium.[116] Several items of Washingtoniana were employed during the dedication. Among these were the Bible which Washington used when initiated into Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 in 1752, the trowel and gavel Washington used while laying the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol building, the Bible on which Washington took the presidential oath of office and a silver urn made by Paul Revere which contained a lock of Washington's hair.[2][30][117] A special Masonic ritual was written for the dedication.[117] The ceremony incorporated a 4-foot (1.2 m) high model of the memorial (manufactured by inmates at the Lorton Reformatory),[34] and the pouring of wine, oil and corn (Masonic symbols) from gold and silver pitchers onto the model.[2][117] The pitchers were made by metalsmith Olaf Saugstadt.[2] The invocation was given by the Rt. Rev. W. Bertrand Stevens, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles.[116] The benediction was given by William J. Morton, Rector of Christ Church, Alexandria (the church where Washington worshipped).[116]

Construction of the interior

[edit]

1930s

[edit]Construction on some of the exterior and nearly all of the interior of the memorial continued after its May 1932 dedication. Sheet metal for interior window sashes, doorjambs and other moldings, fixtures and fittings was provided by G.O. Robertson of Delaware; Ernest Gichner of Washington, D.C.; and the E. Van Norden Co. of New York. The Hires-Turner Glass Co. of Rosslyn, Virginia, provided the windows and stained glass. The lighting fixtures were supplied by the Sterling Bronze Works, while electrical supplies were furnished by the National Electrical Supply Co. of Washington and A.L. Ladd of Alexandria. Four firms oversaw the plumbing and sewage work: Earl Riley, the D.C. Engineering Co., Potomac Clay Works and the Thos. Somerville Co. The interior heavy hardware as well as some heavy internal equipment was supplied by Henry H. Meyer & Co. of Washington, D.C., while lighter hardware and fixtures were supplied by Worth Hulfish & Sons of Alexandria, Baldwin-Stuart Co. of Hartford, Connecticut and Sargent & Co. of New York. Many of the non-marble floors were covered in cork (provided and installed by the David E. Kennedy Co.) and carpeting was provided by Woodward & Lothrop (the department store chain). Acoustic tile was used in many rooms to dampen the echoes produced by the granite walls. This tile was provided by the George P. Little Co. Terrazzo (faux marble flooring) work was done by the V. Foscato Co. of New York. Much of the interior woodwork was supplied by W.A. Smoot & Co. of Alexandria. Interior painting was done by the W.W. MacCallum Co. of Alexandria, while the terracotta (unglazed baked ceramic) decorations were provided by Ernest Simpson of Alexandria. The aluminum for interior work was supplied by the Aerocrete Corporation and worked and molded into forms by the Aluminum Company of America.[56] Gold vein and Tennessee pink marble were used to line the walls of the first floor atrium and the second floor memorial hall and ceilings on both floors were plastered. But by the end of 1933, no heating had been installed in the second floor hall.[118]

Despite the immediate flurry of work on the memorial after its dedication, construction and decoration of the interior slowed significantly over the next two decades. The Great Depression and World War II left both funds and building materials in short supply.

The association wished to complete the memorial hall, the north lodge room and the Alexandria-Washington replica lodge room on the second floor of the memorial. To complete the rooms and hallways leading to them would cost about $193,000. Although fund-raising for the effort began, in 1936 the organization learned that it had to complete the library and elevators in the tower first.[119] In February 1931, Florence M. Lemert, widow of Rae John Lemert, Grand Historian of the Grand Lodge of Montana, donated more than 6,000 books and manuscripts about Masonic history and Masonry to the memorial as a means of founding a national Masonic library.[120] With these books in danger of deterioration, a library had to be constructed immediately and at least one elevator installed in order to reach the library room in the tower. Additional landscaping had to be done in order to reduce the fire danger in the area, walls had to be erected around the land to prevent the public from cutting across the property and roads had to be re-graveled and maintained.[119]

In 1935, the GWMNMA set aside the fourth floor as a "States Memorial Hall" (where each state's Grand Lodge could recognize its famous Masons), the sixth floor as a Masonic library and the eighth floor as a museum.[67] The third, fifth and seventh floors had not yet been assigned a function.[67] But these plans were not carried out. After the death of Louis Watres in June 1937, Elmer R. Arn, Past Grand Master of Ohio, was elected president of the association as his successor.[3] Four large lighting sconces were added to the second floor memorial hall in 1938, with the $4,000 cost of their installation paid for by the General Grand Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star.[121] In 1939, the granite steps leading up to the portico, the walls containing the patio which surrounds the memorial and the stone balustrade for the granite steps were installed.[109] Several hundred plants were also added to the landscaping.[109]

1940s

[edit]

In February 1941, the association reported its first big fundraising season since the memorial's dedication, receiving $100,000 in cash donations.[122] In 1941, the association raised an additional $70,000, leaving it with total funds on hand of $225,000.[3] By now, the total cost of completing the structure had risen to $6 million.[3] The GWMNMA agreed to spend $60,000 in 1942 in order to finish the south lodge room on the second floor[123] and dedicate it to the Blue Lodge. The sum also would cover the cost of finishing the room in the southwest corner of the second floor to house the Alexandria-Washington Lodge's Washingtoniana.[3] Five empty lots on Shooter's Hill were also purchased in 1942, so that a large building could not be built next to the memorial. Additionally, the United States Department of Commerce provided, free of charge, equipment for lighting the building and tower as an aid to aviation. The association paid to have the equipment installed. In February 1942, Representative Sol Bloom donated an oil painting of Washington in full Masonic regalia to the memorial that year as well.[3] Bloom was a member of Pacific Lodge No. 233 in the state of New York and had served as director of the Washington Bicentennial Commission. Artist Hattie Elizabeth Burdette painted the picture in 1932. Actor Tefft Johnson modeled for the portrait, posing in the Masonic apron and wearing the same jewel Washington himself had worn. The chair in the painting also belonged to Washington and the pedestal and background cloth belonged to the Alexandria-Washington Lodge. The painting had been used to advertise the Washington Bicentennial and Bloom donated it to the memorial in memory of his wife (who had died in 1941).[124]

The Blue Lodge room and Alexandria-Washington Lodge replica room were finished in late 1942. During the following year, one of the granite columns in the memorial cracked and was repaired.[124]

Work on the interior did not really begin in earnest until after the war.[14] It was not until May 1945 that the room dedicated to the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (the Shriners) on the north side of the first floor was begun.[125] Placed in the finished room was an original oil painting of Shrine co-founder William J. Florence (valued at $5,000), a copy of the Shrine's Ritual in the handwriting of co-founder Walter M. Fleming, a collection of jewels, and other items.[126] In time, the Shriners would furnish two more rooms on ground floor at a total cost of $168,000.[126][127] In 1946, the association received a major donation of about $154,700 which went to its maintenance fund (which now had to be at least $3 million to generate enough funds to keep the structure maintained).[128]

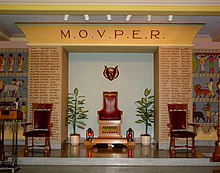

At the GWMNMA's annual meeting in February 1947, the Alexandria-Washington Lodge Replica Room was dedicated. The association also voted to allot one of the rooms in the unfinished tower to the Mystic Order of Veiled Prophets of the Enchanted Realm (also known as "the Grotto"), which had raised $25,000 to finish the room. The Supreme Council, Scottish Rite (Southern Jurisdiction, USA) donated $100,000 to finish the north lodge room on the second floor and dedicate it to Cryptic Masonry. Prior to this donation, the association was unsure whether appendant bodies of Freemasonry should be allowed to occupy rooms in the memorial. The Southern Jurisdiction's donation effectively ended this debate. It also encouraged many Grand Lodges (state organizations) of Masonry to make large donations to the memorial, bringing new life to the memorial's fund-raising efforts. The association also agreed to expend funds to build a kitchen and dining room, hang bronze doors on the first floor and install bronze grillwork for the heating and ventilation system on the first floor.[129] Two other major decisions were made in 1947 as well. Long-time memorial architect Harvey W. Corbett presented his plans for completing the memorial's interior and sculptor Bryant Baker discussed his plans for a life-size statue of George Washington to adorn the memorial hall.[128] The Order of DeMolay, the young men's affiliate of Freemasonry, had won the association's approval for a campaign to raise money for a bronze statue of George Washington back in 1934.[130] Baker proposed a marble statue that would cost $50,000 to $60,000 and stand on a pedestal worth $7,000 to $10,000. The association also began work on its first elevator. The Otis Elevator Company was awarded this contract on October 23, 1947. Designed to fit into the southeast stairwell, the company overcame the 7.5 degree incline of the stairwell by putting wheels on one side of the elevator car to keep it vertical.[129] The memorial's dining room was completed at the end of 1947, and its first use was for a meeting of the GWMNMA in February 1948.[131]

The Grotto dedicated its finished room (designed to house its archives) on the third floor of the building in February 1948.[127][132] The association, meanwhile, outfitted the first floor auditorium with handrails and bronze windowsills and HVAC ventilation grills.[129] The association also made the decision to begin fund-raising for a number of other projects at the memorial. These included designing, manufacturing and installing stained glass windows in the second floor memorial hall, designing and painting murals on the walls of the memorial hall, finishing the roof over the auditorium and portico, installing marble over the rough cement in the interior stairwells and replacing the large wooden doors at the memorial's entrance with bronze doors.[133] That same year, President Harry S. Truman[134] presented the memorial with a replica of the Great Seal of the United States which was 7 feet (2.1 m) in diameter and lit from within.[135] The sign had originally topped of the United States Government Printing Office headquarters, but had been damaged by lightning.[135] Removed and listed as scrap, a Freemason noticed the sign in a government warehouse and asked that it to be donated to the memorial.[135] A presentation ceremony was set for June 24, 1948. Truman's arrival at the presentation was significantly delayed, for he had spent the morning giving military orders to begin the Berlin airlift.[135]

By September 1949, the memorial was still "nowhere near finished."[136] None of the tower rooms in floors three through nine were finished, although the observation deck was under construction.[136] The Scottish Rite agreed to fund the observation deck.[127] The observation deck was accessible only by a circular stairway.[136] In late 1949, the Cryptic Lodge Room (also known as the "North Room") was finished[137] and the two elevators were installed on the north and south side of the building.[136] The room contained seating for 450 and an organ (which was used for the first time during the room's dedication ceremony).[137][138] To avoid piercing the second floor's memorial hall, the elevators slanted inward at 7.5 degrees.[9][136][139] They were 61 feet (19 m) apart on the first floor, but only 4.5 feet (1.4 m) apart at the observation deck.[136] They were the only slanting elevators in the world when installed,[136] and the motors for them had to be passed up through the shafts in order to get them to the roof.[140] Other decorative changes were made by late 1949 as well. A woven Persian carpet, the largest in the world and worth $1 million, was donated to the memorial by Sarkis Nahigian (a Masonic member from Chicago).[136] (It was installed in the Alexandria-Washington Replica Lodge Room. But it had to be folded in order to fit in the room, which caused wear on the rug. The rug was removed after several years and reinstalled in the memorial hall on the second floor.)[129] In the Memorial Hall, two stained glass windows designed and manufactured by Robert M. Metcalf were being installed. Bronze doors, grillwork and window sashes had been installed throughout the first floor, the first floor assembly hall was completed, the kitchen and dining room were finished, the north and south corridors on the first floor were completed and an addition to the heating plant installed.[141] The "Hall of Presidents" was also finished. This walkway on the upper level of the auditorium contained plaques depicting presidents of the United States who were Masons.[142] The Shriners, too, completed their rooms on the first floor.[143]

At some point during 1949, Bryan Baker's sculpture of George Washington was changed from marble to bronze.[136] The statue and its base were both paid for that year.[141]

1950s

[edit]

Baker's 17-foot high (5.2 m) bronze statue of Washington was finally unveiled on February 22, 1950.[130] President Truman, past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Missouri, dedicated the statue and delivered a major foreign policy address at its unveiling.[130] The same year, muralist painter Allyn Cox was hired to paint murals throughout the memorial depicting allegorical Masonic events from history as well as scenes from the life of George Washington.[144][145] The Grand Lodge of California donated the funds for these murals.[146] Cox also designed six stained glass windows for installation above the murals,[146] each depicting a famous Masonic patriot (such as Benjamin Franklin and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette).[147] The windows were executed and installed by stained glass artist Robert Metcalf.[146]

In 1951, the General Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons agreed to fund the completion of the room on the fifth floor and dedicate it to Holy Royal Arch Masonry.[127] That same year, two more Metcalf windows were installed in the memorial hall, the chimes were installed on the 10th floor, and a ladder (acting as a staircase) was placed to provide access to the 10th floor from the ninth floor. A water tank was installed on the fifth floor (to help ensure high pressure) and plumbing extended to the eighth floor, and air conditioning placed in the second floor South Lodge Room. A spiral staircase was added between the third and ninth floors to provide an emergency exit.[148] It was also in 1951[148] that the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania sponsored the completion of the memorial's sixth-floor main library.[127] Outside the memorial, the northwest parking lot was paved and two flagpoles placed outside the main entrance.[148]

Work on the memorial continued in 1952, although most of the work was not finished until a year later. The ninth floor observation deck remained unfinished (although money had been donated to enclose it in a suicide-proof iron cage), and only two floors were open to the public. But the sixth floor library was dedicated on February 22, and later that year Allyn Cox's sketches for the memorial hall murals were approved.[149] Finally, with the second-floor auditorium nearing completion, the memorial association authorized the expenditure of funds for the Moller Organ Co. to begin design and construction of a pipe organ for this space.[150] By early 1953, however, the observation deck was finished and opened for use, and the second inclined elevator began to be installed.[151] Problems with the shaft, however, delayed its completion.[150] Additional internal construction was also completed at this time. The building plans had called for two sets of stairs to descend from the second floor's memorial hall to the first floor's assembly hall. These stairs had never been completed, however, and the space had been used for storage for years. Now funds were available to build the staircases. In order to do so, the unfinished space beneath the main portico was turned into a storage room, and the stairs were installed. Contractors also resealed the exterior of the tower and the second floor roof parapet to prevent water from leaking into the memorial.[151] By the end of 1953, the remaining stained glass windows in the memorial hall were installed.[150]

In 1954, the 42-rank Moller organ was installed in the main auditorium.[152] The $50,000 for the organ had been donated by the Grand Lodge of New Jersey in 1930.[67][150] The marble staircases between the first and second floors were also completed,[153] and the fifth floor with its Royal Arch Masonry room was almost finished as well.[154] The memorial association now began reconsidering some of its plans. It was clear now that there was no need for a "States Remembrance Room" on the fourth floor, and that the eighth floor did not have enough space to hold all the Washingtoniana in the possession of the Alexandria-Washington Lodge. So the association resolved to make the fourth floor a Washington museum, while leaving the eighth floor open.[154]

Allyn Cox's mural on the south wall of the memorial hall was completed in early 1955. Although a mural on the ceiling of the memorial hall had also long been planned, the association decided to forgo this.[155] In February 1955, Theodor Vogel, Grand Master of the United Grand Lodges of Germany, presented the memorial association with intricate wood carvings depicting the Four Crowned Martyrs (in this case, Claudius, Castorius, Nicostratus, and Symphorian). The carvings were hung in the memorial library.[156] That same year, the Knights Templar asked that their assigned room be moved from the seventh to the eighth floor.[127] This request was quickly granted, although it left the seventh floor unoccupied. Throughout the year, Allyn Cox continued to work on murals in the Royal Arch Masonry room and on the mural on the north wall of the memorial hall. At the end of the year, the north and south steps from the parking lots to the first floor were completed. William and Annetta Childs of Oklahoma donated an electronic, automated carillon to the memorial, which was installed in the tenth floor.[157]

The following year, the north side elevator was finally completed.[157] With the elevators freed from the need to carry construction materials and workmen, the tower was finally opened to the public.[158] A number of exterior projects remained, however: granite facing for the upper terrace walls, bronze trim for the main doors, bronze lighting standards for the portico, granite facing for the lower terrace walls, and granite facing for the back of the auditorium. Some interior work was also needed. For example, holes had been drilled in the marble floor of the memorial hall so that electric plugs could be installed for lighting fixtures.[159] The unassigned seventh floor finally found a sponsor as well. That year, the Grand Central Council of Cryptic Masonry agreed to sponsor the floor, and by year's end had raised half the funds necessary to complete and furnish the floor.[160]

The Royal Arch Room was dedicated on April 20, 1957, by Vice President of the United States Richard Nixon.[161] The four bays in the room remained unfinished for many years, however, and were curtained off.[162] The same year, the Southern and Northern Jurisdictions of the Scottish Rite dedicated the George Washington museum on the memorial's fourth floor[163] (although there were no display cases or other furnishings to permit the Washington museum to open).[159] The day before Easter (April 20), the Knights Templar dedicated their eighth floor chapel. At year's end, the second of Allyn Cox's murals for the memorial hall was completed.[160]

Work on the seventh-floor Cryptic Masonry room was well under way by late 1957[160] and the room was dedicated on February 12, 1958.[164] A change was made to the portico as well that year. The portico had been designed so that large bronze plaques could be installed on either side of the main doors. Fundraising for these plaques had not gone well, leaving two gaping holes in the marble walls. The memorial association decided that marble, rather than bronze, plaques be installed in these spaces. Quotations from George Washington's Masonic correspondence were selected and inscribed on these marble plaques. Additionally, the bronze doors for both sets of elevators were also installed (at a cost of $18,000).[165] At the end of the year, the memorial association spent more than $108,000 to finish the granite facing of the auditorium.[164]

In 1959, a large bronze bust of Washington by sculptor Donald De Lue (commissioned by the Grand Lodge of Louisiana, and originally destined for their headquarters) was donated to the museum.[163] The Scottish Rite offered to finance the completion of the fourth floor's museum.[164]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]In 1962, artists Dwight Franklin and Robert N.S. Whitelaw completed 12 dioramas (worth $75,000) to be placed in the assembly hall and which depicted key incidents in Washington's life.[166] These dioramas had been part of the original decorative scheme for the memorial, with eight dioramas (two for each corner) to be placed in the assembly hall. Due to a dispute over the subject matter, 12 rather than eight dioramas were ordered.[167] Air conditioning was added to the North Lodge (form the Cryptic Lodge) Room in 1963.[168]

But despite these achievements, by 1964 the memorial still wasn't finished. More than 150,000 people a year were visiting the memorial, but the Washington museum was still unfinished.[169] A major push to finish the museum came after 1966, when Washington's descendants—Anne Madison and Patty Willis Washington—donated the Washington family's collection of papers and memorabilia to the museum.[9] The donation included a large portrait of George Washington and his family, as well as the Washington family Bible.[170] Only after this donation was made were funds for the museum's completion finally raised.[171]

The late 1960s saw the completion of the memorial. In February 1966, Senator Everett Dirksen (a Mason) dedicated the George Washington museum on the memorial's fourth floor.[172] The dedication meant that the final room in the tower was now complete and open to the public. In 1967, the city of Alexandria changed the street layout around the memorial. As part of this alteration, the memorial granted the city a 12-foot (3.7 m) wide access path (or "alley") between the memorial's access road and Park Road.[170] Since the back wall of the auditorium had never been faced with granite, the protruding steel reinforcing bars had rusted. These were removed in 1968, as they were no longer fit for use. Finally, in 1970, the 40-year-old oil-burning heating plant was replaced with new natural gas-burning boilers, the city of Alexandria donated a back-up electrical generator to keep the tower lit in case of blackouts, additional lighting for the tower was installed, and additional landscaping work completed.[173]

The memorial was considered complete in 1970.[14][174] However, the granite facing still remained incomplete. The memorial association finally raised the funds to finish the facing in July 1972, and the facing was finished in March 1973.[175] The tower, too, remained only partially lit. But the Grand Lodge of New York provided the funds to finish the lighting, and the final tower exterior illumination was completed in the summer of 1973.[176]

About the building

[edit]

The George Washington Masonic National Memorial is Neoclassical in style.[48] Portions of the building are also in the Greek Revival and Romanesque Revival styles.[60] The columns which form the portico, are in the first floor assembly hall and the second floor main hall, and on the first tier of the tower are Doric.[67] However, the columns on the second tier of the tower are Ionic, and the columns on the third tier of the tower are Corinthian.[67]

The memorial consists of nine floors. The first (or "ground") floor appears, from the outside, to be part of the foundation. In the center of the first floor is the Grand Masonic Hall. The Grand Masonic Hall features eight large green granite columns, four on each side of the hall.[67] The Grand Masonic Hall is 66 feet (20 m) long, 66 feet (20 m) wide, and 20 feet (6.1 m) high.[67] The 12 dioramas commissioned in the mid-1960s are located in this hall.[31] At the western end of the hall are short steps which lead up to an alcove in which a bronze bust of George Washington was placed in 2008.[177] The semicircular alcove surrounding the bust contains murals depicting Masonic events in the life of Washington. For many years, the Great Seal of the United States donated by President Truman to the memorial in 1948 was displayed in this hall, but it was removed in the late 1990s.[135] Large, medium, and small meeting rooms are on the north and south sides of the Grand Masonic Hall. All three rooms on the north side contain exhibits which document the history and activities of the Shriners.[8][14] Many of the models in these rooms depict Shriner charities, and one model is a miniature mechanical version of a Shriners' parade.[14][80] The medium-sized room on the memorial's southwest corner contains an exhibit about Freemasonry in general.[14] The medium-sized meeting room (the George Washington Room) and large-sized meeting room (the Andrew Jackson Room) on the south side are generally closed to the public but can be rented as meeting space.

The second (or "main") floor appears, from the outside, to be the main level of the memorial.[31] The Parthenon-inspired portico with its Doric columns forms the primary entrance to the memorial.[67] The portico is supported by eight fluted columns of pink Conway granite 5.92 feet (1.80 m) in diameter and 33 feet (10 m) high,[67] each weighing 63 short tons (57 t).[146] The bas-relief medallion of Washington in profile which is incorporated into the pediment above the portico is 7 feet (2.1 m) across.[67] Bronze doors lead the way into the memorial. Once inside the memorial, to the left is the Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22 Replica Lodge Room, which faithfully duplicates the look of the lodge room at the time Washington presided over the lodge.[14][31] This room contains several items which belonged to Washington as well as historic items (such as furniture) from the Alexandria-Washington Lodge.[31][80] Behind the Master Mason's chair in this room is the William Joseph Williams portrait of Washington in his Masonic garb.[31][178] Along the south side of this floor is the South Lodge Room,[14] which replicates the Neoclassical look of the Alexandria-Washington Lodge when it was located in the Alexandria City Courthouse. This room is used for meetings of Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22 as well as other Masonic lodges who wish to use it for meetings while visiting the memorial.

The main feature of the second floor is the Memorial Hall, which is 100 feet (30 m) long, 66 feet (20 m) wide, and 51 feet (16 m) high.[67] Eight green granite columns (four on each side) support the roof of the Memorial Hall.[31][139] Each column is 38.5 feet (11.7 m) high, 4 feet (1.2 m) wide at the base, and weighs 63 short tons (57 t).[146] On the western end of the hall is the 17 feet (5.2 m) high bronze statue of Washington in Masonic regalia.[31][80] It weighs 7 short tons (6.4 t).[139] The floor is composed of Tennessee marble in a geometric design, and the walls are of Missouri marble.[146] In the corners of the Memorial Hall are four 8-foot (2.4 m) high bronze lamps, donated by the Order of the Eastern Star (a Masonic social organization composed primarily of women).[146] On the north and south sides of the Memorial Hall are murals by Allyn Cox depicting Washington attending a service at Christ Church, Alexandria and of Washington (in Masonic garb) laying the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol building.[9][14][139] The murals were photographed in their entirety for the first time in 2000.[179]

Behind the Memorial Hall to the west is the semicircular Memorial Theater,[180] which was designed to seat 1,000.[67] (After being reconfigured, it seats just 358 today.) The Memorial Theater features a fan-shaped ceiling and 16 St. Genevieve marble columns around its perimeter.[108] Around the mezzanine are 14 bronze bas-relief portraits of presidents of the United States who were Freemasons.[181] Behind the stage is the portrait of Washington donated by Rep. Sol Bloom. In the balcony in the theater's eastern end is the Moller organ donated by Grand Lodge of New Jersey.[67] On the north side on the first floor is the North Lodge Room.[14] An open-beam arched ceiling marks this room, which is in the half-timbered style and has balconies on three sides and a stage in front.[182] This is the meeting room of Andrew Jackson Lodge No. 120, as well as other Masonic lodges who wish to use it for meetings while visiting the memorial.[182]

The tower contains the third through ninth floors. The tower is divided into four sections, each smaller in circumference than the one below.[9] There are two floors in the first, second, and third section, but only one floor in the fourth section. The third floor contains exhibits about the history, charitable activities, and socializing that various Masonic bodies engage in. The third floor used to be solely dedicated to the Mystic Order of Veiled Prophets of the Enchanted Realm ("the Grotto"), and housed the organization's archives.[8][14] But beginning in February 2012, the third floor was renovated to contain displays about other appendant bodies as well (although the Grotto's display in the room remains by far the largest).[183] The fourth floor contains the George Washington Museum, which is maintained with funding from the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite of the Southern and Northern Jurisdictions of the United States.[14] The Donald De Lue bronze statue of Washington is located in the museum,[184] which also contains many items used or owned by Washington.[8] The fourth floor is double the height of the third floor, with a mezzanine that contains additional exhibits. The fifth floor is the same height as the third floor, and is dedicated to exhibits and symbols important to Royal Arch Masonry.[8] This floor is in the Egyptian Revival and ancient Hebraic architectural styles.[14][80] It also contains a replica of the Ark of the Covenant (curtains automatically open and close to reveal the replica to visitors).[80] The sixth floor contains the Memorial Library.[14][180] This floor is double the height of the fifth floor, and like the fourth floor contains a mezzanine. The seventh floor is the same height as the third and fifth floors, and is dedicated to Cryptic Masonry (the second part of the York Rite system of Masonic degrees).[8][14] The room is a symbolic replica of the legendary crypt beneath the Temple of Solomon where secrets and treasures were kept.[14] It also contains murals which depict key events mentioned in Cryptic initiation rituals (such as the murder of Hiram Abiff, architect of Solomon's Temple). The eighth floor is the same height as the seventh floor, and contains a chapel dedicated to the Knights Templar.[14][80] It is in the early French Gothic architectural style. Like the fourth and sixth floors, it is double the height of the third and fifth floors but it lacks the mezzanine found on the fourth and sixth floors. The stained glass windows in this chapel depict four scenes from the Christian Bible:[80] Jesus healing the blind, the Sermon on the Mount, the crucifixion of Jesus, and the ascension of Jesus into heaven. The ninth floor is the same height as the third, fifth, and seventh floors, and contains both the Tall Cedars Room and the observation platform. The Tall Cedars of Lebanon is a social group for Master Masons, and their room on the ninth floor depicts King Solomon's throne room and symbols important to this group.[14] The observation platform, which rings the exterior of the ninth floor, is accessible only from this room.[14]

The structure is capped by a step pyramid with seven steps.[9][185] The light fixture atop the pyramid is in the shape of a double keystone (a shape which is of symbolic importance to Freemasons).[80]

The memorial sits on 36 acres (15 ha) of parkland.[80] Since the GWMNMA is a nonprofit organization, the memorial and its land are not taxed.[80] The first and second floors are open to all visitors,[31] but visitors are required to be accompanied by a docent when visiting the other floors.[8] Tours occur every hour.[8] Tours were free for most of the memorial's history, but a fee began to be charged in 2010.[139]

Building operations

[edit]

Finances and organizational changes

[edit]The George Washington Masonic National Memorial is the only Masonic building supported by all 52 grand lodges of the United States.[80][180][186] By 1983, the memorial had 35 full-time staff and an annual budget of $500,000.[80] At that time, each person initiated into Freemasonry in the United States paid a one-time-only $5 fee which was deposited in the memorial's building maintenance fund.[80]

But despite this income and its endowment, the memorial faced a severe financial crisis in the 1980s.[187] A significant decline in the number of Freemasons in the United States led to strong declines in donations to the memorial's maintenance and endowment funds.[187] The building needed significant repairs, but making them left the maintenance fund exhausted.[187] For the first time in its history, the GWMNMA considered taking out a loan to pay for the repairs and the upkeep of the memorial.[187] The financial crisis was avoided when several Grand Lodges adopted a per capita assessment on their members to keep the memorial afloat, and the GWMNMA began a series of fundraisers and the sale of gifts to generate additional income.[187]

In 1993, to make the memorial a more central part of the cultural life of Alexandria, the memorial began renting out its meeting rooms, assembly halls, and theaters to private groups for various kinds of functions.[178] In 1994, the memorial's operating budget was $600,000.[178] By 2000, the GWMNMA's endowment had grown to $12 million.[188] But revenues were still inadequate. In the 1920s and 1930s, many Grand Lodges had enacted a per capita assessment on their members to provide general support for the GWMNMA. But by 2003, only one-quarter of all Grand Lodges still did so.[189] That year, the GWMNMA began pushing Grand Lodges to assess an automatic per capita contribution again.[189] The program met with some success. But despite this growth, in 2004 the endowment was still only half the size it needed to be.[190]

The GWMNMA also made some organizational changes. Between 1910 and 1951, the association had had just three presidents (Shryock, Watres, and Arn). The GWMNMA board of directors decided that imposing term limits on the office of the president would give board members a chance to become president and implement new ideas more frequently. In 2004, the GWMNMA amended its constitution to impose a limit of three one-year terms on presidents of the association.[191] In 2008, the number of presidential terms limit was reduced further to two one-year terms.[192]

For the calendar year 2008,[193] the GWMNMA had 21 staff, total revenues of just over $1 million, total expenses of about $1.6 million, and total assets of about $15.8 million.[194] The association's endowment, however, was not as robust as it had once been. About $500,000 had been spent (primarily on building repairs), and losses due to the economic downturn were significant (close to $2.7 million).[194] The endowment had dropped from about $11.8 million at the end of 2007 to about $8.7 million at the end of 2008.[194]

Renovations

[edit]Major changes have occurred to the memorial and the nearby area since it was completed in 1970. The King Street Metro station opened about three blocks from the memorial in November 1983.[195] Storm windows on the exterior of building were also replaced about this time, at a cost of $75,000.[80] Microwave transmission antennas were added to the top of the memorial in 1990 to help the City of Alexandria improve police radio transmissions in the area.[196]

For the memorial's 60th anniversary in 1992, the George Washington museum exhibited a special collection of Washingtoniana. A rhinestone Past Master's Masonic "jewel," owned by Martha Washington and sold by the Washington family at the time of her death, was part of the display.[9] Also loaned to the museum was the desk in the Maryland Statehouse on which Washington resigned his commission in the Continental Army at the end of the American Revolution.[9] The Washington museum's collection was recataloged at this time as well.[9] This led to some historic discoveries. It had long been known that the Washington family Bible had a half-page of the family torn out, but the recataloging discovered that one of Washington's descendants had ripped it out to go into the cornerstone of the Washington Monument on July 4, 1848.[9] A map, hand-drawn by Washington to show the route a British military expedition took to Ohio in 1790, turned up in a desk.[9] Also uncovered was a book on the use of artillery sent to Washington by a Scotsman, and a 1798 encyclopedia (the first printed in America) specially ordered by Washington.[9] Researchers also uncovered a print of Washington's deathbed scene, and the stub of a candle carried by Freemasons in a ceremony after his death.[9]

In 1999, the George Washington Masonic National Memorial was branded for the first time as a Masonic building. Although twin sidewalks used to run directly up the eastern slope of Shooter's Hill toward the memorial's front steps,[80] these were partially replaced by curving cement paths and a large Square and Compasses (the Masonic symbol) in a landscaped setting.[14][197] The new symbol cost $250,000,[198] and is 70 feet (21 m) wide by 60 feet (18 m) long.[197] (It is visible from aircraft landing at nearby Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.)[197]