Timeline of Los Angeles

Appearance

The following is a general historical timeline of the city of Los Angeles, California in the United States of America.

Pre-Columbian era

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

- 8,000 BCE – Chumash and Tongva Tribes inhabited the Los Angeles Basin for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans in the area.

- Angeles Mesa skeletons Remains of Indigenous people Discovered in Ballona Plain,1924

- La Brea Woman 10,250 year old BP Remains of Indigenous woman Discovered in La Brea Tar Pits,1914

- 2,000 BCE to 700 CE, the Uto-Aztecan (formerly known as Shoshonean) peoples entered the LA basin, absorbing or displacing the previous Hokan-speaking peoples

15th century

English exploration

- 1542

- October 8: Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sails from Catalina Island to San Pedro Bay and names it Bay of Smoke.

- October 9: Cabrillo Anchors in Santa Monica Bay then Departs North.

- November 23: Cabrillo on his return trip Anchors and Lands in Catalina Island to overwinter and make repairs. The Party of Explorers departed a short time later.

17th century

- 1602

- November 20: Sebastián Vizcaíno Anchors and lands in Catalina Island for a short time during his voyage northward.[citation needed]

18th century

Spanish colonization

- 1769

- Late July: José Francisco Ortega scout leader for the Portolá expedition is the first non-indigenous person to explore the LA Basin via a land trail.

- 1771

- September 8: Original San Gabriel Mission is Built near Whittier Narrows.

- 1776 – Original San Gabriel Mission is destroyed in a flash flood forcing the Priest to move the location 5 miles north. Building the new Mission San Gabriel Arcángel.

- 1781

- September 4: El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles de Porciuncula founded in colonial New Spain by 44 settlers, 20 of whom were of African American or Native American descent.[1][2]

- 1790's – Vicente Sanchez Adobe is built in the Eastern Foothills of Baldwin Hills

- 1795 – Construction commences on the Casa de Rancho San Antonio completed in 1810.

19th century

- 1818 – Avila Adobe built.[3]

- 1820 – Los Angeles Pueblo Population: 650 [4]

Mexican period

- 1821

- Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, Land Granted to Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez, by CA Governor.

- September 28: In Mexico City, the Mexican Empire declares independence; news would reach California months later.[5]

- 1822

- Joseph John Chapman an Anglo-American then one of the earliest English-speaking settlers and builders of Mexican Alta California. Chapman Helps to build the roof of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles .[6]: 393

- April 9: A junta in Monterey headed by governor De Solá swear an oath allegiance of the Alta California Province to the Mexican Empire; in the following days, public oaths were taken in the pueblos and missions of Alta California.[5]

- May: José Palomares goes to Monterey as the elector selected to represent the pueblo de Los Ángeles in the election of a deputy from the province to the Congress.[5]

- 1823

- Rancho Las Ciénegas, Land Granted to Francisco Avila, by CA Governor.

- 1826

- November 27: Jedediah Smith an Anglo-American Explorer arrives at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel from the Great Salt Lake area, making him the first American to reach Alta California via a land route

- 1827 – Jonathan Temple and John Rice opened the first general store in the pueblo, soon followed by J. D. Leandry.[7]

- 1828 - Rancho La Brea, Land Granted to Antonio Jose Rocha and Nemisio Dominguez, by LA Mayor.

- 1830 – Los Angeles Pueblo Population: 730.[1]

- 1831

- Jean-Louis Vignes bought 104 acres (0.42 km2) of land located between the original Pueblo and the banks of the Los Angeles River. He planted a vineyard and prepared to make wine.[8]

- Rancho Rosa Castilla, Land Granted to Juan Ballesteros, by CA Governor.

- 1833 – Los Angeles Trade and commerce further increased with the secularization of the California missions by the Mexican Congress. Extensive mission lands suddenly became available to government officials, ranchers, and land speculators. The governor made more than 800 land grants during this period to wealthy Californios.

- 1834

- Governor Pico married Maria Ignacio Alvarado in the Plaza church. It was attended by the entire population of the pueblo, 800 people, plus hundreds from elsewhere in Alta California.

- Rancho San Pascual, Land Granted to Juan Marine, by CA Governor.

- 1835

- May 23: On the advice of the territory's deputy, José Carrillo, Los Angeles, is given the title of Ciudad and was declared the capital of the Alta California Territory by the Mexican Congress.[1] The de facto capital remained in Monterey until decades later and the decision furthered political tensions in the territory.

- 1836 – The Indian village of Yaanga was relocated near the future corner of Commercial and Alameda Streets.

- 1839 – Francisco Sepúlveda is granted land Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica which later developed as the west side of Los Angeles.[9]

- 1841 – Los Angeles City Population: 1,680 [4]

- 1845 – The Indian village of Yaanga was relocated again to present-day Boyle Heights.

American invasion

- 1846

- August 6: US Navy Commodore Robert F. Stockton lands Military Force in San Pedro and sets up camp near Casa de San Pedro

- August 13: Stockton and Frémont rendezvous South of Los Angeles to commence the Capture of the City.

- September 23–30: Siege of Los Angeles, a Civil rebellion against American occupation led By Jose Maria Flores recaptures Los Angeles from U.S. forces, U.S. Officer Gillespie is forced to retreat to San Pedro Camp.

- October 6: U.S. troops under William Mervine land in San Pedro to attempt to recapture Los Angeles.

- October 8–9: Battle of Dominguez Rancho, US Marines engage in a battle with the Mexican Californios, the Mexicans defeated the United States Military forces. causing them to retreat once again.

- 1847

- January 8–9: Battle of Río San Gabriel, Mexican's block path into Los Angeles at Pico Rivera. American Troops are Victorious and the Mexicans Retreat.

- January 10: Battle of La Mesa, Los Angeles taken by U.S. forces.[1][10]

- January 13: Treaty of Cahuenga, Signed by Andrés Pico & John C. Frémont ends American military action and completes the American Conquest of California.

American period

- 1848

- February 2: Los Angeles becomes part of U.S. territory per Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

- 1849 – Lieutenant Edward Ord surveyed Los Angeles to confirm and extend the streets of the city. His survey put the city into the real-estate business, creating its first real-estate boom and filling its treasury.[11] Street names were changed from Spanish to English.

- 1850

- April 4: Los Angeles incorporated.[1]

- September 9: Los Angeles becomes part of the new U.S. state of California.[1]

- Population: 1,610 city; 3,530 county.[1]

- Los Angeles County established.

- 1851 – Los Angeles Star, city's first newspaper, begins publication.[12] Hugo Reid, who was married to an indigenous woman Victoria Reid published his series The Indians of Los Angeles County in the newspaper as part of his campaign to be named Indian agent

- 1854 – Round House constructed.

- 1855 – First City public school building built.[1]

- 1859 – Los Angeles County votes to secede from California to form the Territory of Colorado, voting 1,407–441 in favor of secession.[13][page needed] Congress throws out secession proposal the following year amid the Civil War.[citation needed]

1860s

- 1860 – Los Angeles Soap Company in business, founded by John A. Forthmann. [14]

- 1865 – Loyola High School (Los Angeles) opens.[15]

- 1866 – Town Square established.[16]

- 1868 – Street lighting installed.[16]

- 1869

- October 26: Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad begins operating.[17]

- William Rosecrans Buys Rosecrans Tract a very large portion of land in South Los Angeles an investment in which he subdivides and sells developing lots eventually beginning settlement in the area.

1870s

- 1871

- October 24: Anti-Chinese unrest.[1]

- Evening Express newspaper begins publication.[18]

- San Pedro Harbor development begins.[19]

- 1872 – First African Methodist Episcopal Church established.[16]

- 1873 – Los Angeles Daily Herald newspaper begins publication.[18]

- 1874

- May: Tiburcio Vásquez California's first Notorious Celebrity was caught and apprehended after a shootout in Today's West Hollywood

- 1875 – Los Angeles and Independence Railroad begins operating to Santa Monica.[1]

- 1876

- September 6 – Southern Pacific Railroad (San Francisco-Los Angeles line) begins operating Los Angeles' first link to transcontinental railroad.[1]

- Cathedral of Saint Vibiana built.[16]

- Pico Canyon Oilfield drilled in LA Outskirts, making it the first commercially successful oil well in the Western United States[20][21][22][23] and is considered the birthplace of California's oil industry.

- 1877

- First oranges shipped to eastern markets.[1]

1880s

- 1880

- University of Southern California opens.

- Population: 11,183 city;[1] 33,381 county.

- 1881 – Los Angeles Daily Times begins publication.[18]

- 1882 – Los Angeles State Normal School opens.[1]

- 1883 – City Railroad Company established.[24]

- 1884 – Child's Grand Opera House opens.[25]

- 1886

- Kansas City-Los Angeles railway begins operating.

- City Fire Department[26] and Elysian Park established.

- Pasadena and Santa Monica incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- Many people arrive as a result of railroad rate war; speculative real estate boom begins.[1]

- 1887

- Peak of 1880s Southern California real estate boom; many towns laid out.[1]

- Los Angeles Athletic Club incorporated.

- April 20 – Occidental College founded.[1]

- Pomona incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- 1888

- Land boom collapses.[1]

- Southern Pacific's Arcade Depot opens.

- Chamber of Commerce founded.

- California Club incorporated.

- Long Beach incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- 1889

- City Parks Department[27] and Los Angeles Oil Exchange founded.

- Orange County established.[28]

1890s

- 1890 – Population: 50,400 city; 101,454 county.

- 1891 – Courthouse built.[1]

- 1892

- Redondo Beach incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- February – Oil discovered within Los Angeles City limits.[1]

- 1893

- Bradbury Building constructed.[1]

- July 4 – Mount Lowe Railway opens north of Pasadena.

- July 29 – La Grande StationLa Grande Station railway opens.

- 1894 – Fiesta de Los Angeles begins.[1]

- 1895

- Highland Park becomes part of the City of Los Angeles.[1]

- Los Angeles Consolidated Electric Railway taken over by bondholders and renamed the Los Angeles Railway[29]

- 1896

- May – Congress approves $2,900,000 for deep-water harbor at San Pedro.[1]

- 1897 – Los Angeles Country Club founded.

- 1898

- September 1: Henry E. Huntington and Isaias W. Hellman syndicate purchase Los Angeles Railway and begin expanding it[29]

- March 5: Griffith Park presented to Los Angeles by Col. Griffith J. Griffith.[14]

- 1899

20th century

1900s

- 1901

- Angels Flight funicular begins operating.

- Children's Hospital founded.

- November 1 – Huntington group incorporates the Pacific Electric Railway of California[29]

- 1902

- Tally's Electric Theater opens.[25]

- Los Angeles takes over water system.[1]

- 1903

- Los Angeles Examiner newspaper begins publication.[1]

- Braly Building constructed.

- 1905

- Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad begins operating.[1]

- Design of the seal of the City of Los Angeles adopted.

- Vernon incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- Southern California Buddhist Church, the first in Los Angeles, is established on Jackson Street with its first resident minister Koyu Uchida.[30]

- 1906

- Alexandria Hotel in business.[14]

- Shoestring strip, to connect Wilmington to Los Angeles, annexed to City of Los Angeles.[31]

- Glendale, Huntington Park, and Watts incorporated in Los Angeles County.[1]

- 1907

- Port of Los Angeles[17] and City Club of Los Angeles[32] established.

- Silver Lake Reservoir built.[14]

- Los Angeles Ostrich Farm[14] and Los Angeles Alligator Farm open.

- 1908

- Mount Wilson Observatory begins operating in Los Angeles County.

- October 1: Construction begins on Owens River Aqueduct.[1]

- 1909

- Selig Polyscope Company relocates to Los Angeles.[33]

- City Market Wholesale Produce Terminal built.[34]

- San Pedro and Wilmington become part of the City of Los Angeles.[1]

1910s

- 1910

- October 1: Los Angeles Times bombing.[1]

- East Hollywood and Hollywood become part of City of Los Angeles.[31]

- Trolleybus service operates Laurel Canyon.[35]

- Population: 319,200 city; 504,131 county.

- 1911

- Nestor Studios begin operating.[33]

- Pacific Electric Railway Company[1] created from merger of eight streetcar companies.

- Los Angeles College created.[1]

- Burbank incorporated in Los Angeles County.

- San Fernando incorporated in Los Angeles County.

- 1912 – County of Los Angeles Public Library established.[1]

- 1913

- Los Angeles Aqueduct completed.[33]

- La Brea Tar Pits excavation begins.[36]

- 1914

- Southern Pacific's Central Station and Southwest Museum[1] open.

- "First ship via Panama Canal arrives."[1][17]

- Beverly Hills incorporated in Los Angeles County.[16]

- 1915

- Universal Studios begins operating.[16]

- San Fernando Valley becomes part of City of Los Angeles.[31]

- Breed Street Synagogue active.

- Japan-Los Angeles steamship begins operating.[16]

- Area of city: 288 square miles.[37]

- 1916

- Westgate becomes part of City of Los Angeles.[31]

- Lincoln Motion Picture Company in business.[38]

- 1917

- Culver City incorporated in Los Angeles County.[16]

- The Southern California Buddhist Church is renamed to Hongwanji Buddhist Church of Los Angeles and is moved to Yamato Hall.[30]

- 1918

- Warner Bros. Studios begin operating.[16]

- Los Angeles Philharmonic[25] and Otis College of Art and Design founded.

- 1919

- September – Southern branch of University of California is founded.[1]

1920s

- 1920

- Population: 576,673 city;[39] 936,455 county.

- Douglas Aircraft Company in business in nearby Santa Monica.[1]

- 1921

- May 2: the Los Angeles Steamship Company starts their five times per week overnight passenger and freight service to San Francisco

- Hollywood Legion Stadium opens.[1]

- Hollywood Masonic Temple and Hollyhock House (residence) built.

- Watts Towers sculpture construction begins.

- Chouinard Art Institute founded.

- Ambassador Hotel in business.

- 1922

- KFI, KHJ and KNX radio stations begin broadcasting.[16]

- Hollywood Bowl (amphitheater) and Grauman's Egyptian Theatre open.

- Rose Bowl completed in Pasadena.[1]

- 1923

- Post World War I building boom reaches its peak.[1]

- Hollywoodland sign erected.[40]

- Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum opens.

- Biltmore Hotel in business.

- Angelus Temple built.[15]

- Illustrated Daily News begins publication.[1]

- 1924 – Harding High School established.

- 1925

- Grand Olympic Auditorium opens.

- Junior League www.jlla.org and Yogananda Self-Realization Fellowship[41] established.

- A new building for the Hongwanji Buddhist Church, designed by Edgar Cline, is built.[30][42]

- 1926

- Orpheum Theatre, El Capitan Theatre,[43] and 28th Street YMCA[44] open.

- June – New Central Public library building completed.[1]

- Shrine Auditorium rebuilt.

- Venice and Watts become part of City of Los Angeles.

- La Opinión Spanish-language newspaper begins publication.

- 1927

- Grauman's Chinese Theatre opens.

- May 5, Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel opens for business.

- Barnsdall Art Park established.

- 1928

- Los Angeles City Hall built.

- March 13: Collapse of St. Francis Dam in nearby San Francisquito Canyon.[1]

- Huntington Library opens in Los Angeles County.[1]

- 1929

- August: Graf Zeppelin (aircraft) arrives from Tokyo.[15]

- Academy Awards begin.[45]

- Los Angeles Board of Trade Building and Bullocks Wilshire department store built.

- Nuart Theatre opens.

1930s

- 1930

- Olvera Street restored.[46]

- Hollywood Reporter begins publication.

- Greek Theatre[16] and Pantages Theatre[43] open.

- Highland Park synagogue built.

- Population: 1,238,048 city; 2,208,492 county.

- Burbank airport begins operating.

- 1931

- The Chateau Marmont is converted from an apartment building to a hotel.

- Figueroa Street Tunnels open.

- The Hongwanji Temple in Kyoto confers betsuin status to their temple in Los Angeles, which is renamed as the Hompa Honwanji Los Angeles Betsuin.[30]

- 1932 – 1932 Summer Olympics held.

- 1933

- March 10: 1933 Long Beach earthquake.

- June 6: Frank L. Shaw becomes mayor.

- October 12: Los Angeles Garment Workers Strike of 1933 begins.

- Los Angeles Sentinel newspaper[16] and Daily Variety begin publication.

- 1934 – Los Angeles Science Fiction Society formed.[12]

- 1935 – Griffith Park Planetarium dedicated.[1]

- 1936

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles established.

- Crossroads of the World shopping mall built.

- 1937

- Los Angeles purchases Mines Field for a municipal airport.[1]

- 1938

- Los Angeles flood of 1938.[1]

- China City developed.[34]

- CBS Columbia Square built.

- Mayor Shaw ousted; Fletcher Bowron becomes mayor.[1]

- 1939

- Union Station opens.[1]

- Chandler's fictional detective novel The Big Sleep published.[16]

1940s

- 1940

- Arroyo Seco Parkway opens.[16]

- United States Court House built.

- 1941

- Los Angeles Airport in operation.

- Pueblo Del Rio housing complex built.

- Turnabout Theatre of puppets established.[46]

- 1942

- February: Incarceration of Japanese, Germans and Italians to internment camps begins.

- US-Mexico Bracero program begins.

- Parking meters installed.[16]

- Battle of Los Angeles occurs.

- 1943 – Ethnic Zoot Suit Riots occur.[15]

- 1944 – Imperial Courts and Jordan Downs housing projects built.[47]

- 1946

- 1947 – KTLA television begins broadcasting.[12]

- 1948 – In-N-Out Burger is founded

- 1949 – Los Angeles Valley College opens in the Valley Glen neighborhood of Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley.

1950s

- 1950

- Fictional Sunset Boulevard film released.[16]

- Population: 1,970,358 city; 4,151,687 county.

- 1951 – Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority created.[24]

- 1953 – Four Level Interchange highway begins operating.[50]

- 1954 – Church of Scientology[15] and Getty Museum[16] open.

- 1955

- Nickerson Gardens housing complex built.[47]

- Disneyland amusement park opens in nearby Anaheim.[16]

- 1956 – Capitol Records Tower built.[16]

- 1957 – Ferus Gallery of art opens.[51]

- 1958 – Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team active.[52]

- 1959

- Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena opens.

- Grammy Award begins.[53]

- KPFK radio begins broadcasting.[54]

- Sister city relationships established with Eilat, Israel; and Nagoya, Japan.[55]

1960s

- 1960

- July: 1960 Democratic National Convention held.

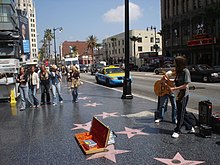

- Hollywood Walk of Fame established.[16]

- Los Angeles Lakers basketball team active.[16]

- 1961

- Theme Building constructed at Los Angeles Airport.

- Pacific Electric Railway ceases Red Car interurban operations (last line in service was Long Beach Line).[56]

- 1962

- Los Angeles Herald-Examiner newspaper in publication.

- City Cultural Heritage Board created.

- Dodger Stadium opens.[16]

- Sister city relationship established with Salvador, Brazil.[55]

- 1963

- Last Yellow Car metropolitan streetcar service runs.[57][58]

- Vincent Thomas Bridge opens.

- Century City development begins.

- 1964

- Whisky a Go Go nightclub[16] and Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (concert hall) opens.[16]

- UCLA Labor Center and Los Angeles Master Chorale founded.

- Sister city relationship established with Bordeaux, France.[55]

- 1965

- August 11–17: Watts Riots.[59]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art opens on Wilshire Boulevard.[51]

- Marina del Rey harbor opens in Los Angeles County.[16]

- 1966

- Los Angeles Zoo opens.[16]

- Gemini G.E.L. art studio founded.[51]

- 1967

- Super Bowl I is held at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

- City's Community Analysis Bureau established.[60]

- Two California Plaza built.

- The Advocate newsletter begins publication.[12]

- Mark Taper Forum (theatre)[61] and Brockman Gallery of art[51] open.

- Forum (arena) opens in nearby Inglewood.[16]

- Los Angeles Kings hockey team active.

- Sister city relationship established with Berlin, Germany.[55]

- 1968

- June 5: Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel.

- July 3: Crosby, Stills and Nash first harmonize during an impromptu meeting at the home of Joni Mitchell in Laurel Canyon. The group will come to epitomize the Laurel Canyon sound identified with L.A. into the 1970s.

- Sister city relationship established with Lusaka, Zambia.[55]

- 1969 – The Tate–LaBianca murders are committed by the Manson Family cult/commune/gang who are arrested by year's end.

- Sister city relationship established with Mexico City, Mexico.[55]

- Formation of the Crips and Pirus

- November: The new Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple is completed.[30][42]

1970s

- 1970 – Chinatown Service Center established.[34]

- Former Leave it to Beaver actor Ken Osmond joins the Los Angeles Police Department

- The trial of the Manson Family cult starts on July 15.

- 1971

- January 25: Charles Manson and his cult's members are convicted of the Tate-LaBianca Murders.

- January 28: A federal building on Los Angeles Street is bombed, killing a teenage employee.

- February 9: 1971 San Fernando earthquake.

- March 29: The Manson Family is sentenced to death.

- Six Flags Magic Mountain (originally named Magic Mountain) opens in Valencia.

- Los Angeles Convention Center opens.

- California Institute of the Arts opens in nearby Valencia.[51]

- Sister city relationships established with Auckland, New Zealand; and Busan, South Korea.[55]

- 1972

- Womanhouse art event occurs.[51]

- Self Help Graphics & Art active.

- Sister city relationships established with Mumbai, India; and Tehran, Iran.[55]

- 1973

- Tom Bradley becomes mayor.[62]

- Aon Center built.

Formation of the Bloods

- 1974 – Security Pacific Plaza built.

- 1975 – Chinese Historical Society of Southern California founded.

- 1976 – Los Angeles City Historical Society founded.[63]

- 1977 – X (musical group) formed.

- 1978

- L.A. Weekly begins publication.

- President Carter makes his first visit (May 4)

- Los Angeles Conservancy founded.

- 1979 – Sister city relationship established with Taipei, Taiwan.[55]

- President Carter makes his second visit (May 5)

- The City Council passes Los Angeles' first homosexual rights bill on June 1 which Mayor Bradley sings on the next day, June 2.

1980s

- 1980 – Population: 2,966,850 city; 7,477,421 county.

- 1981 – Sister city relationship established with Guangzhou, China.[55]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) publishes the first report from here of symptoms of what would be later known as AIDS, with Los Angeles at least second or third highest reporting city for it after New York's #1 and San Francisco's # 2.

- Mötley Crüe formed.

- 1983

- Crocker Tower built.

- Red Hot Chili Peppers (musical group) formed.

- 1984

- L.A. surpasses Chicago as the second largest city in the United States.[64]

- 1984 Summer Olympics held.

- Forever 21 clothier in business.

- "Power of Place" group formed.

- West Hollywood incorporated in Los Angeles County.

- Sister city relationships established with Athens, Greece; and Saint Petersburg, USSR.[55]

- 1985 – Latino Theater Company founded.

- City Council passes Los Angeles anti-AIDS-discrimination bill that Mayor Bradley signs

- "Night stalker", aka Night Prowler killer Richard Ramirez is arrested in East Los Angeles.

- 1986

- Devastating fire at the Central Library.

- Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles established.

- Los Angeles Opera active.

- Sister city relationship established with Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.[55]

- Proposition U passed

- 1987 – Whittier Narrows earthquake

- 1988 – Museum of Jurassic Technology founded.

- 1989

- U.S. Bank Tower built.

- Sister city relationship established with Giza, Egypt.[55]

1990s

- 1990

- Hollywood Bowl Orchestra founded.

- Sanwa Bank Plaza built.

- Population: 3,485,398.[39]

- Sony Pictures Entertainment headquartered in nearby Culver City.

- Sister city relationship established with Jakarta, Indonesia.[55]

- Metro Blue Line opens, re-establishing light rail in the city

- 1991

- Gas Company Tower and 777 Tower built.

- Maxine Waters becomes U.S. representative for California's 29th congressional district.[65]

- Sister city relationship established with Kaunas, Lithuania.[55]

- 1992

- April 29: Rodney King riots begin.[59]

- Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance founded.

- Sister city relationship established with Makati, Philippines.[55]

- 1993

- Richard Riordan becomes mayor

- Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority created.

- Metro Red Line opens.

- Sister city relationship established with Split, Croatia.[55]

- 1994 – January 17: 1994 Northridge earthquake.

- 1995

- City website launched.[66][67][68]

- Los Angeles Independent Film Festival and LA as Subject project[69] begin.

- Drudge Report begins publication.

- Metro Green Line opens.

- 1996

- Loyola Marymount University's Center for the Study of Los Angeles founded.[70]

- Council on American–Islamic Relations Los Angeles chapter founded.[71]

- Museum of Television & Radio opens in Beverly Hills.

- 1997

- American Apparel clothier headquartered in Los Angeles.

- The Getty Center opens in Brentwood.

- 1998 – Los Angeles Almanac begins publication.[72]

- California Science Center opens to the public.

- 1999 – Staples Center (sports arena) opens.

- 2000

- August: 2000 Democratic National Convention held.[73]

- Los Angeles Police Rampart scandal report issued.

21st century

2000s

- 2001

- James Hahn becomes mayor

- Kodak Theatre opens.

- Disney California Adventure opens adjacent to Disneyland.

- 2002 – Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels built.

- 2003

- Walt Disney Concert Hall[74] and Chinese American Museum[34] open.

- Los Angeles Derby Dolls (rollerderby) team formed.

- Metro Gold Line opens.

- 2004 – National Day Laborer Organizing Network headquartered in Los Angeles (approximate date).[citation needed]

- 2005

- Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority homeless census begins.[75]

- Antonio Villaraigosa becomes mayor.[15]

- Sister city relationship established with San Salvador, El Salvador.[55]

- Metro Orange Line opens.

- 2006

- LA Weekly Detour Music Festival begins.

- Sister city relationships established with Beirut, Lebanon; and Ischia, Italy.[55]

- Metro Purple Line opens.

- 2007

- May 1: 2007 MacArthur Park rallies.

- Los Angeles Theatre Center opens.[76]

- Sister city relationship established with Yerevan, Armenia.[55]

- 2008

- Anime Expo first arrives at the Los Angeles Convention Center

- First DineLA Restaurant Week was held[77]

- 2009 – Los Angeles Times' Mapping L.A. project begins.

- Metro Sliver Line opens.

2010s

- 2010

- 2011

- October 1: Occupy Los Angeles begins.[80]

- QuakeBot in use.[81]

- 2012

- Metro Expo Line opens.

- Los Angeles Review of Books begins publication.

- Wilshire Grand Tower, the new tallest building in the city begins groundbreaking in downtown LA.

- September 19–21: Endeavour makes final landing at LAX.

- FIGat7th Reopens the newly constructed center happened in fall 2012.[82]

- 2013

- Eric Garcetti becomes mayor.

- Population: 3,884,307.[83]

- 2014

- DataLA (city data website) begins publication.[60]

- The long-stalled Metropolis Towers breaks ground and begins construction in downtown LA.

- 2015

- August: Shade balls put into Los Angeles Reservoir during 2015 California drought.[84]

- A massive natural gas leak in the Santa Susana Mountains near Porter Ranch, also known as Aliso Canyon gas leak, was discovered.

- 2016

- Los Angeles Rams NFL football team moves back to Los Angeles.

- ET94 Space Shuttle fuel tank arrives in LA at the California Science Center.

- 2017

- Measure S fails

- Los Angeles Chargers NFL football team moves back to Los Angeles.

- Los Angeles population reaches 4 million.[85]

- Los Angeles is selected as the host city for the 2028 Summer Olympics.

- 2018 – Woolsey Fire burns across Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

- 2019

- Typhus outbreak spreads in Los Angeles.[86]

- Bracero Monument by Dan Medina installed with 19-foot-tall featuring a bronze sculpture of a Mexican migrant and his family.[87][88]

- Teachers in LA went on strike at the beginning of the year with about 30,000 following a string of success across the country.[89]

- The construction of $44 million affordable housing of low income in Willowbrook, California, is now completed.[90]

- Construction of Oceanwide Plaza, halted in 2019 in Downtown LA.

2020s

- 2020

- January 26 – American professional basketball player Kobe Bryant dies in a helicopter crash.

- Los Angeles was hardest-hit by COVID-19 pandemic, which put few thousands of residents out of work, and shifted others to work at home.

- Oceanwide Plaza remains uncompleted as Chinese foreign real estate investment capital pulled out due to the China–United States trade war.

- 48 apartments could replace single family home in downtown L.A.[91]

- Hotel-Residential project at Wilshire takes another step forward, which will be completed in 2023. There are 14 residences in affordable units.[92]

- May 29–31 – Civil Unrest during George Floyd protests occurs in Downtown Los Angeles, Central LA, & Santa Monica

- September 8 – SoFi Stadium opens in Inglewood, which occupies the former site of the Hollywood Park Racetrack.

- October 11 – The Los Angeles Lakers win the NBA Finals, their first championship since 2010.

- October 27 – The Los Angeles Dodgers win the World Series, their first championship since 1988.

- 2021

- November 16: The naming rights of the Staples Center is acquired by Crypto.com, renaming it to the Crypto.com Arena.

- 2022

- February 13: Los Angeles Rams win Super Bowl LVI at SoFi Stadium.

- May 22: Amazon opens its first clothing store in Los Angeles.[93]

- October 9 - 2022 Los Angeles City Council scandal, an audio recording surfaced of a private meeting involving Los Angeles City Council members and a union leader that involved racist and disparaging comments and led to a local political scandal.

- October 12: City council president Nury Martinez resigns amid a racism scandal.

- December 12: Karen Bass is sworn in as mayor, becoming the city's first woman to serve as mayor.

- 2023

- May–November: The 2023 Hollywood labor disputes occur primarily in Los Angeles and New York City.

- 2024

- April–May: Pro-Palestinian campus protests occur in a number of LA-based universities, including UCLA and USC.

- August 15: The Intuit Dome opens in Inglewood.

- September: The Bridge Fire burns in Angeles National Forest.

Future events

See also

- History of Los Angeles

- List of mayors of Los Angeles

- List of districts and neighborhoods of Los Angeles

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Los Angeles, California

- Timeline of California[94]

- Timelines of other cities in the Southern California area of California: Anaheim, Bakersfield, Long Beach, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, Santa Ana

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be Federal Writers' Project 1941, p. 405: "Chronology"

- ^ Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration of Northern California (1939). "Chronology". California : a guide to the Golden state. Prelinger Library. New York: Hastings House.

- ^ "Los Angeles, as a Pedestrian", New York Times, December 19, 2014

- ^ a b Northrop, Marie E., ed. (December 1960). "The Los Angeles Padron of 1844 as Copied from the Los Angeles City Archives". Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. 42 (4): 360–417. doi:10.2307/41169490. JSTOR 41169490.

- ^ a b c Bolton, Herbert E. (1919). "The Iturbide Revolution in the Californias". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 2 (2): 188–242. doi:10.2307/2505905. ISSN 0018-2168.

- ^ Bancroft, H. H. History of California, 1801–1824 (1886) Free ebook

- ^ Newmark, Marco R. (1942). "Pioneer Merchants of Los Angeles". Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. 24 (3): 76–97. doi:10.2307/41168008. JSTOR 41168008.

- ^ Gaughan, Tim (June 19, 2009). "Where the valley met the vine: The Mexican period". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Map of Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica, Santa Monica: Calendar of Events in the Making of a City, 1875–1950". Santa Monica Public Library. 1875. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Monnette 1915.

- ^ Robinson, William Wilcox (1966). Maps of Los Angeles; From Ord's Survey of 1849 to the Boom of the Eighties. Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop.

- ^ a b c d McNamara 2010.

- ^ Ellison, William Henry (October 1, 1913). The Movement for State Division in California, 1849–1860. JSTOR. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly.

- ^ a b c d e Federal Writers' Project 1941: "Los Angeles"

- ^ a b c d e f Starr 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab "Historical Timeline of Los Angeles". LA Tourism & Convention Board. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c Port of Los Angeles. "Timeline of Historic Events". City of Los Angeles. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c "US Newspaper Directory". Chronicling America. Washington DC: Library of Congress. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Newmans 1903.

- ^ "Mentryville Path to Be Repaired". Daily News (Los Angeles). June 17, 2007. ("Mentryville was established in 1876 after workers drilled what became the first commercially successful oil well in the West.")

- ^ Judy Raphael (October 8, 1998). "Boomtown Bash: Tiny town of Mentryville, site of 1876 oil rush, will hold festival fund-raiser". Los Angeles Times. ("The well, known as Pico No. 4, was the first commercially successful oil well in the western U.S.")

- ^ Nicholas Grudin (August 3, 2003). "Ghosts of an Era: Mentryville Is a Monument to Both the Start and Decline of the Area's Oil Drilling Industry". Daily News (Los Angeles). ("Scofield formed California Star Oil Works, and with skilled oil man Alex Mentry, tapped the first commercial oil well in California – Pico No. 4.")

- ^ Jonathan Gaw (February 21, 1993). "Oil in a Day's Work The Boom May Be Over, but a Few Wells Pump On". Los Angeles Times. ("Oil men had been groping around the canyons of the area since 1876, when the first commercially successful oil well west of Pennsylvania was built several miles south of Lechler's ranch in Pico Canyon.")

- ^ a b Blueprint America 2008.

- ^ a b c Smith 2007.

- ^ Directory 1915.

- ^ Parks 1988.

- ^ "How Orange County Seceded from Los Angeles". KCET. August 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c Friedricks 1992, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e "About us". Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple (Nishi). Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Auditor 1917.

- ^ City Clubs in America, Chicago: City Club of Chicago, 1922

- ^ a b c "Events (timeline)". New Perspectives on the West. USA: Public Broadcasting System. 1996.

- ^ a b c d "Chinese in America: Timeline". Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (April 2, 2013). "CityDig: The Trackless Trolleys of Laurel Canyon". LAmag -Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles.

- ^ "Animals of the La Brea Tar Pits: Timeline". Los Angeles: Page Museum. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Guinn 1915.

- ^ S. Torriano Berry; Venise T. Berry (2015). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of African American Cinema (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-4702-4.

- ^ a b Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990, US Census Bureau, 1998

- ^ Not for Tourists 2014.

- ^ Timothy Miller, ed. (1995). America's Alternative Religions. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-1311-2.

- ^ a b "JANM Campus | Japanese American National Museum". www.janm.org. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ a b "Movie Theaters in Hollywood, Los Angeles, CA". CinemaTreasures.org. Los Angeles: Cinema Treasures LLC. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Nina Mjagkij (1994). Light in the Darkness: African Americans and the YMCA, 1852–1946. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2801-3.

- ^ "Academy Awards through the years (timeline)". Los Angeles Times. March 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Los Angeles Public Library. "Visual Collections". City of Los Angeles. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Independent Lens 2008.

- ^ Jeffrey M. Pilcher (2008). "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?". Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies. 8: 26–38. doi:10.1525/gfc.2008.8.1.26.

- ^ Best of LA 1999.

- ^ "A history of cities in 50 buildings", The Guardian, UK, 2015

- ^ a b c d e f Art in Context 2011.

- ^ "Dodgers Timeline". MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Grammys history and winners through the years (timeline)". Los Angeles Times. January 26, 2014.

- ^ Pulido 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Sister Cities of Los Angeles". City of Los Angeles. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Rasmussen, Cecilia (March 23, 2003). "From the Archives: Did Auto, Oil Conspiracy Put the Brakes on Trolleys?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Long, Tony. "March 31, 1963: L.A. Streetcars Take Their Last Ride". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028.

- ^ "Who killed L.A.'s streetcars? We all did". Los Angeles Times. November 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "On This Day", New York Times, retrieved December 30, 2014

- ^ a b Vallianatos 2015.

- ^ James Fisher (2011). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of Contemporary American Theater: 1930–2010. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7950-8.

- ^ Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis, ed. (2005). "Chronology". To Make Our World Anew: a History of African Americans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983893-6.

- ^ "History of the Los Angeles City Historical Society". lacityhistory.org. January 5, 2017. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ LOS ANGELES REPLACES CHICAGO AS SECOND CITY Retrieved August 1, 2020

- ^ "California". Official Congressional Directory: 103rd Congress. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. 1993. hdl:2027/uc1.l0072691827.

- ^ "Welcome to the Wiring of the City", Los Angeles Times, May 1995

- ^ "Feuer Calls for Guidelines on Officials' Internet Sites", Los Angeles Times, December 1995

- ^ "Official Site of L.A. City Government". Archived from the original on October 31, 1996 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- ^ "LA as Subject". Retrieved December 30, 2014 – via University of Southern California Libraries.

- ^ "Online resources related to Southern California history". LA History Archive. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "CAIR CALIFORNIA | Greater Los Angeles Area » Our Mission & Vision". ca.cair.com. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Resources". Los Angeles City Historical Society. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Center for the Study of Los Angeles. "CSLA Research Collection: List of Collections". Loyola Marymount University. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Walt Disney Concert Hall through the years (timeline)". Los Angeles Times. September 13, 2013.

- ^ "L.A. County has its most accurate count yet of its homeless population", Los Angeles Times, June 4, 2015

- ^ "Los Angeles Theatre Center | History and Background". thelatc.org. 2014. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Fine dining becomes affordable". Daily Bruin. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "Los Angeles (city), California". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Largest Urbanized Areas With Selected Cities and Metro Areas (2010)". US Census Bureau. 2012.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street: Timeline". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "How an algorithm helped the LAT scoop Monday's quake", Columbia Journalism Review, March 18, 2014

- ^ "City Target Opens Next Week, Sprinkles and the Melt Sign on at FIGat7th in Downtown LA | DTLA RISING". October 5, 2012. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The 15 Cities with the Largest Numeric Increase from July 1, 2012 to July 1, 2013" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 2014.

Vintage 2013 Population Estimates

- ^ "L.A. Covers Its Reservoirs With Millions of 'Shade Balls'", City Lab, Atlantic Monthly Group, August 12, 2015

- ^ "Los Angeles' Population Jumps By 40,000, Now Tops 4 Million". May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Typhus Epidemic Worsens in Los Angeles". nbclosangeles.com. February 1, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Dan Medina, The Bracero Monument, Los Angeles". Public Art in LA. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Monument honoring 'braceros,' Mexican migrant workers, unveiled in downtown L.A." Los Angeles Times. September 30, 2019. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Hess, Abigail Johnson. "Teachers in Los Angeles want more than a raise—here's why over 30,000 just went on strike". CNBC. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ "$44-Million Senior Affordable Development Completed in Willowbrook". Urbanize LA. February 7, 2019.

- ^ "48 Apartments Could Replace Single-Family Home in South L.A." Urbanize LA. October 15, 2020.

- ^ "Hotel-Residential Project at Wilshire & La Brea Takes Another Step Forward". Urbanize LA. October 15, 2020.

- ^ Hicks, Jasmine (May 25, 2022). "Amazon's first clothing store opens its doors in Los Angeles". The Verge. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939), "Chronology", California: Guide to the Golden State, American Guide Series, New York: Hastings House – via Open Library

Bibliography

- "History of Los Angeles City". Newmans's Directory and Guide of Los Angeles. 1903. hdl:2027/hvd.hn3nkq.

- J.M. Guinn (1915). "How the Area of Los Angeles City was Enlarged". Publications. 9. Historical Society of Southern California.

- Los Angeles City Directory, Los Angeles Directory Co., 1915–, 1915

- Orra Eugene Monnette (1915). California Chronology: A Period of Three Hundred and Fifty Years, 1510–1860. Los Angeles: Standard printing Company.

- "Annexation and Area of City". Report of the Auditor of the City of Los Angeles, California. 1917.

- Federal Writers' Project (1941), Los Angeles: a Guide to the City and its Environs, American Guide Series, NY: Hastings House – via Hathi Trust + Chronology

- Friedricks, William B. (1992). Henry Huntington and the Creation of Southern California. Columbus, OH.: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0553-4.

- Robert Mayer, ed. (1978), Los Angeles: a Chronological & Documentary History, 1542–1976, American Cities Chronology Series, Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications

- "100 Years of Recreation and Parks" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. 1988.

- "Best of LA", Los Angeles Magazine, Emmis Communications, July 1999

- Catherine Parsons Smith (2007). "Music Chronology for Los Angeles, 1781–1941". Making Music in Los Angeles: Transforming the Popular. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93383-5.

- Kevin Starr (2007). "Chronology". California: A History. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-43075-5.

- "Timeline: Driven to Despair: Los Angeles". America in Gridlock. Blueprint America. USA: Public Broadcasting System. 2008.

- "Timeline: South Central Los Angeles". Crips and Bloods: Made in America. Independent Lens. USA: Public Broadcasting System. 2008.

- Kevin R. McNamara, ed. (2010). "Chronology". Cambridge Companion to the Literature of Los Angeles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51470-5.

- "Art in Context: L.A. from 1945 to 1980 (timeline)". Los Angeles Times. September 15, 2011.

- Laura Pulido; et al. (2012). People's Guide to Los Angeles. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95334-5.

- "Los Angeles Timeline". Not For Tourists Guide to Los Angeles. Skyhorse. 2014. ISBN 978-1-62873-583-3.

- Mark Vallianatos (June 2015), "Uncovering the Early History of "Big Data" and the "Smart City" in Los Angeles", Boom, University of California

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Los Angeles.

- "Los Angeles City Directories, 1875–1942" – via Los Angeles Public Library.