Ol' Rip the Horned Toad

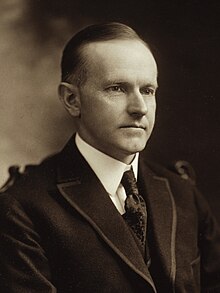

Ol' Rip the Horned Toad (died January 19, 1929) was a Texas horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum), commonly referred to as a "horned toad" or "horny toad", which supposedly survived a 31-year hibernation as an entombed animal following its exhumation from a cornerstone in Eastland, Texas, on February 18, 1928. The lizard became a national celebrity and appeared in the 1920s motion pictures.[1][2] Its name was a reference to American writer Washington Irving's fictional character Rip Van Winkle.[1][3] The same year, a Texas political delegation led by Senator Earle Mayfield presented the docile lizard to President Calvin Coolidge at the White House for his inspection.[4]

Following the creature's fame, horned toads were sold by the thousands as souvenirs at public events, including the 1928 Democratic National Convention.[3] The ensuing mass capture and export of the horned toads resulted in the genus's abrupt decline in West Central Texas and prompted an intervention by the Texas Department of Agriculture.[3]

Decades later, the saga of Ol' Rip inspired Looney Tunes scribe Michael Maltese to write a 1955 animated theatrical short entitled One Froggy Evening.[5] In the cartoon, a construction worker demolishing an old building finds an 1892 time capsule inside a cornerstone.[5] The capsule contains a living toad which is able to sing Tin Pan Alley songs such as "Hello! Ma Baby" and "I'm Just Wild About Harry".[5]

History

Alleged entombment

On July 29, 1897, a four-year-old boy named Will Wood caught a horned toad in Eastland County, Texas.[3][6] His father, Eastland County clerk Ernest E. Wood, decided to test the West Texas tradition that the creatures could survive for many years in hibernation.[3][6] The horned lizard was placed in a time capsule in a cornerstone of the Eastland courthouse along with memorabilia, including a Bible and a bottle of alcohol.[1][6]

Thirty years later, during the Jazz Age, construction workers began to tear down the old courthouse, and town officials scheduled a public event to open the time capsule in mid-February 1928.[7] An ambitious young newspaperman named Boyce House reported on the forthcoming ceremony in his articles for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.[8] House particularly emphasized the mystery of the horned toad which supposedly had been entombed in the capsule since 1897.[8]

As a result of House's sensationalist newspaper articles, a crowd of 1,500 spectators gathered in Eastland, Texas, to witness the opening of the time capsule and to learn the fate of the horned toad.[1][8] Many spectators had traveled more than 25 miles to be present, and hundreds thronged around the makeshift fence that encircled the old courthouse.[8] At exactly four o'clock on Saturday, February 18, 1928, a live horned lizard was allegedly produced from within the time capsule in front of the excited audience.[9][10] Newspaperman Boyce House recalled the chaotic scene:

When the brick wall was pulled away from the cornerstone, the crowd rushed forward, in its excitement, pressing so closely against a worker that he barely had room to ply his pick to break a layer of cement over the top of the stone. Then, he lifted a sheet of metal underlying the cement. As this covering was raised, disclosing the cavity, Rev. F. E. Singleton (pastor of the Eastland Methodist Church), standing beside the cornerstone, leveled a finger and said: "There's the frog!" An oil man, Eugene Day, thrust his hand into the cavity and lifted a flat, dust-covered toad, which he handed to Rev. Mr. Singleton. The pastor handed the creature to Judge Pritchard, who dangled it with a hind leg that all might see. Suddenly, the other hind leg twitched: The frog was alive! [3]

Within days, national newspaper chains reported the discovery of the entombed lizard on their front pages.[3] The New York Times reported the event on its front page with the declarative headline: "Toad Alive After 31 Years Sealed in Texas Cornerstone".[11] The Times article credulously reported:

After the cornerstone was removed, the toad appeared lifeless for some time, but in a little while, it opened its eyes. In about twenty minutes, it began to breathe. The mouth, however, appeared to have grown together. Efforts will be made to induce the toad to take food, and, if necessary, the mouth will be opened by an operation. The toad is now on exhibition.[11]

Following these newspaper reports, zoologists and other scientists began a public debate over whether a Texas horned toad could survive such an extended period without water, sunlight, or oxygen.[12] Dr. Raymond L. Ditmars, curator of mammals and reptiles at the Bronx Zoo, declared the alleged survival of the entombed lizard in Eastland, Texas, to be "utterly impossible".[13] In contrast, preeminent naturalist William T. Hornaday, the curator of the New York Zoological Gardens, asserted that "the incident was possible—and gave an instance from his own experience in Ceylon".[8] Indifferent to this scientific debate, Eastland locals instead ascribed the horned toad's "miraculous" survival for thirty-one years to the presence of the Bible in the time capsule.[14]

National fame

Due to the extensive media coverage, Ol' Rip became a national celebrity.[1][15] The docile lizard was transported to Dallas, Texas, for public exhibition by Will Wood, the same individual who purportedly found the specimen as a boy in 1897. After a public outcry by Eastland inhabitants and profit-hungry business people over removing the famous creature from their otherwise nondescript and insignificant town, Wood returned Ol' Rip to Eastland. Dallas exhibitors promptly sued Wood for $6,000 (equivalent to $106,465 in 2023)[16] for alleged breach of contract.[3]

After this incident, Ol' Rip went on a national tour, and forty thousand spectators viewed him at the Zoological Gardens in St. Louis, Missouri. Later that same year in New York City, motion pictures were produced with Will Wood introducing Ol' Rip, and "a bug-catcher was paid $0.50 (equivalent to $8.87 in 2023)[16] each for insects that the frog devoured to please the cameraman".[3]

The peak of Rip's fame occurred in May 1928 when, during his national tour, the lizard was transported to Washington, D.C., where Texas senator Earle Bradford Mayfield presented the specimen to President Calvin Coolidge.[1][15] A bemused Coolidge purportedly declined to touch the horned toad and merely nudged it with his spectacles.[15] A newspaper article reported the incident:

President Coolidge asked numerous questions concerning his celebrated guest; stroked the frog's back with his horn-rimmed glasses, and then President and Old Rip gazed steadily at each other for a full minute without a sound—Silent Cal had met his match.[3]

As a consequence of the creature's immense fame, horned toads were sold as souvenirs at the 1928 Democratic National Convention in Houston, Texas, for $2.50 (equivalent to $44.36 in 2023).[16][3] The mass capture and export of horned toads for such sales resulted in the genus' precipitous decline in West Texas.[7] According to Texas journalist Boyce House: "So many [horned toads] were shipped out of West Texas that a Department of Agriculture bulletin foretold damage amounting to thousands of dollars if the [export] shipments did not stop inasmuch as horned frogs preyed on insects that would devour [local] crops."[3]

Death and controversy

Soon after his national tour, Ol' Rip died of pneumonia on January 19, 1929.[1] After Ol' Rip's death, the specimen was kept in a tiny satin-lined casket, provided by the National Casket Company,[17] and displayed in the lobby of the new Eastland courthouse.[3]

Decades later, in September 1961, Old Rip briefly disappeared from the museum exhibit, and a ransom note demanded $10,000 (equivalent to $101,960 in 2023)[16] for his return.[18] After a city-wide search, the specimen was recovered.[18] A year later, in 1962, John Connally visited the courthouse while running for governor of Texas for a publicity event.[1] An impetuous Connally lifted the embalmed creature by its hind leg which abruptly detached.[1]

In 1972, Rip's body was again stolen.[19] Soon after, the City of Eastland claimed they had somehow "found" the stolen specimen and returned the object to exhibition.[20] However, museum visitors noted the "recovered" toad now inexplicably had four feet, while the original specimen only had three feet,[20] presumably due to the earlier 1962 incident with John Connally.[1]

In 1976, an anonymous letter was sent to newspapers claiming the original, three-footed specimen was still in the thief's possession, and the City of Eastland had replaced the original specimen with a fake.[20] Angry that "the city of Eastland was building its future around a dried-up horned frog",[20] the letter-writer offered to pay $5,000 (equivalent to $26,772 in 2023)[16] to anyone who could prove the toad in the courthouse was truly Ol' Rip.[20]

Legacy and influence

In 1955, Looney Tunes writer Michael Maltese was inspired by the story of Ol' Rip to write an animated theatrical short entitled One Froggy Evening.[5] In the cartoon, a construction worker demolishing a building finds an 1892 time capsule inside a cornerstone.[5] The capsule contains a living frog, retroactively named Michigan J. Frog years later, which is able to sing Tin Pan Alley songs such as "Hello! Ma Baby" and "I'm Just Wild About Harry".[5]

Old Rip's story was told in the 2004 documentary short ToadSpotting: The Legend of Old Rip.[21]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Scudder & Watkins 2018.

- ^ Newton 2008; Ellsworth 1997; Greenville News 1928, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m House 1938, p. 8.

- ^ House 1938, p. 8; Greenville News 1928, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Michael J. Frog 2017; Gordon 2003.

- ^ a b c Newton 2008.

- ^ a b House 1938, p. 8; Phillips 1929, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Phillips 1929, p. 6.

- ^ Phillips 1929, p. 6; The Kansas City Star 1928, p. 2.

- ^ House 1938, p. 8; The Idaho Statesman 1928, p. 1; Ellsworth 1997.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1928a, p. 1.

- ^ Fremont Tribune 1928, p. 1; Times Record News 1928, p. 1; Wichita Falls Times 1928, p. 6.

- ^ The New York Times 1928b, p. 11.

- ^ House 1938, p. 11: "In the cornerstone with Old Rip had been a copy of the Bible and Arthur Brisbane, in his column read by scores of millions, said that Will Wood believed the frog had derived strength from the presence of the Scriptures. Sermons were preached on the subject."

- ^ a b c d Greenville News 1928, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Newton, Teresa S. "Old Rip". Texas Parks and Wildlife. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Austin American-Statesman 1961, p. 14.

- ^ Fort Worth Star-Telegram 1972, p. 25; Dabney 1976, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Dabney 1976, p. 4.

- ^ ToadSpotting: The Legend of Old Rip at IMDb

Works cited

- "Coolidge Sees Famous Horned Toad of Texas". Greenville News (Friday ed.). Greenville, South Carolina. May 4, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dabney, James (September 10, 1976). "Letter Reawakens 'Rip' Toad Legend". Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Friday ed.). Fort Worth, Texas. p. 4. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Doubts Horned Toad Tale: Dr. Ditmars Calls Survival for 31 Years in Cornerstone 'Impossible'". The New York Times (Tuesday ed.). New York City. February 21, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- "Eastland Asks Old Rip's Return". Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Tuesday ed.). Fort Worth, Texas. April 18, 1972. p. 25. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ellsworth, Ken (March 2, 1997). "A Century Ago Old Rip Was Placed in a Cornerstone". Reporter News. Abilene, Texas: Scripps Newspaper Group. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Frog Lives In Stone 31 Years But Specimen in an Old Texas Courthouse Can't Eat Now". Kansas City Star (Sunday ed.). Kansas City, Missouri. February 19, 1928. p. 2. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Frog Question Acute and Threatens to Become National: Letters, Verbal Testimony and Even Living Specimens of Toads and Frogs Pour Steadily Into Office of Times". Wichita Falls Times (Sunday ed.). Wichita Falls, Texas. February 26, 1928. p. 6. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gordon, David George (December 2003). "Hibernating Hoppers: Can Toads Live Buried for Decades?". MSN Encarta. Redmond, Washington. Archived from the original on December 28, 2003. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- "Horned Frog Alive After Being Buried For Thirty-one Years". Idaho Statesman (Sunday ed.). Boise, Idaho. February 19, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- House, Boyce (February 13, 1938). "Amazing Story of Rip Is Told in Its Entirety". Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Sunday ed.). Fort Worth, Texas. p. 8. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Michigan J. Frog: Biography — American Animated Character". who2.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- Newton, Teresa S. (October 2008). "Legend, Lore & Legacy: Old Rip". Texas Parks and Wildlife. Austin, Texas: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Old Frog Leaps Back Into Case". Austin American-Statesman (Friday ed.). Austin, Texas. September 29, 1961. p. 14. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Phillips, R. K. (February 21, 1929). "Death of Texas Horned Frog Recalls His Hop to Fame". The Knoxville Journal (Thursday ed.). Knoxville, Tennessee. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- Scudder, Charles; Watkins, Chelsea (October 5, 2018). "The strange tale of Old Rip, the horned toad on display in a Texas courthouse". Dallas Morning News (Friday ed.). Dallas, Texas. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Texas Horned Frog Center of Nation-Wide Disputes: Scientists Doubt 31 Year Sleep Story of Reptile". Fremont Tribune (Wednesday ed.). Fremont, Nebraska. February 22, 1928. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Texas Horned Frog Upsets Scientists: 'Impossible!' Says Zoologists But Eastland Toad Still Lives Anyway". Times Record News (Tuesday ed.). Wichita Falls, Texas. February 21, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Toad Alive After 31 Years Sealed in Texas Cornerstone". The New York Times. New York City. February 20, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

External links

- Newkirk, Greg (July 7, 2014). "Meet Ol' Rip, the toad that survived 31 years trapped in a time capsule". Roadtrippers.

- Horned Lizard from the Handbook of Texas Online

- DiMeo, Nate (29 September 2022). "Nee Blinky". The Memory Palace. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "ToadSpotting: The Legend of Old Rip". (January 31, 2004). Esteem Education