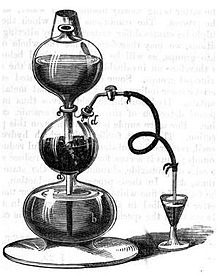

Kipp's apparatus

Kipp's apparatus, also called a Kipp generator, is an apparatus designed for preparation of small volumes of gases. It was invented around 1844 by the Dutch pharmacist Petrus Jacobus Kipp and widely used in chemical laboratories and for demonstrations in schools into the second half of the 20th century.

It later fell out of use, at least in laboratories, because most gases then became available in small gas cylinders. These industrial gases are much purer and drier than those initially obtained from a Kipp apparatus without further processing.

Design and operation

[edit]The apparatus is usually made of glass, or sometimes of polyethylene, and consists of three vertically stacked chambers, roughly resembling a snowman. The upper chamber extends downward as a tube that passes through the middle chamber into the lower chamber. There is no direct path between the middle and upper chambers, but the middle chamber is separated from the lower chamber by a retention plate, such as a conical piece of glass with small holes, which permits the passage of liquid and gas. The solid material (e.g., iron sulfide) is placed into the middle chamber in lumps sufficiently large to avoid falling through the retention plate. The liquid, such as an acid, is poured into the top chamber. Although the acid is free to flow down through the tube into the bottom chamber, it is prevented from rising there by the pressure of the gas contained above it, which is able to leave the apparatus only by a stopcock near the top of the middle chamber. This stopcock may be opened, initially to permit the air to leave the apparatus, allowing the liquid in the bottom chamber to rise through the retention plate into the middle chamber and react with the solid material. Gas is evolved from this reaction, which may be drawn off through the stopcock as desired. When the stopcock is closed, the pressure of the evolved gas in the middle chamber rises and pushes the acid back down into the bottom chamber, until it is not in contact with the solid material anymore. At that point the chemical reaction comes to a stop, until the stopcock is opened again and more gas is drawn off.

Kipp generators only work properly in the described manner if the solid material is insoluble in the acid, as otherwise the dissolved material would continue to evolve gas even after the level dropped. The produced gas often requires further purification and/or drying, due to content of water vapor and possibly mist if the reaction is vigorous.

Examples for prepared gases and their educts

[edit]For successful use in a Kipp's apparatus, the solid material has to be available in lumps large enough to stay on the retention plate without falling through its holes.

- Hydrogen from iron flakes or zinc and hydrochloric acid or diluted sulfuric acid respectively.

- Carbon dioxide from pieces of marble (calcium carbonate) and hydrochloric acid

- Hydrogen sulfide from iron(II) sulfide and hydrochloric acid

- Acetylene from calcium carbide and water

- Methane from aluminium carbide and lukewarm water, deuterated methane (CD4) from aluminium carbide and heavy water

- Chlorine from potassium permanganate, calcium hypochlorite, or manganese dioxide and hydrochloric acid; also from barium ferrate and hydrochloric acid

- Oxygen from calcium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide with a bit of nitric acid; also from barium ferrate and dilute sulfuric acid

- Ozone from barium peroxide and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Nitric oxide from copper turnings and diluted nitric acid

- Nitrogen dioxide from copper turnings and concentrated nitric acid

- Ammonia from magnesium nitride and water, deuterated ammonia when heavy water is used;[1] also from calcium oxide and solution of ammonium chloride

- Carbon monoxide from pumice impregnated with oxalic acid and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Sulfur dioxide from pumice impregnated with sodium metabisulfite (or sufficiently large pieces of sodium metabisulfite) and concentrated sulfuric acid, or from sodium hydrogen sulphite and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Hydrogen chloride can be prepared from lumps of ammonium chloride and concentrated sulfuric acid[2]

Generally, weak acidic gases can be released from their metal salts by dilute acids, and sometimes just with water:[1]

- Hydrogen sulfide from metal sulfides

- Hydrogen selenide from selenides, e.g. aluminium selenide

- Hydrogen telluride from tellurides, e.g. aluminium telluride

- Some hydrocarbons can be prepared from certain carbides

- Methane from methanides

- acetylene from acetylides

- Methylacetylene and propadiene from sesquicarbides, e.g. magnesium carbide

- Ammonia from certain nitrides, e.g. magnesium nitride

- Phosphine from phosphides, e.g. calcium phosphide (often produced together with small amount of diphosphane)

- Arsine from arsenides, e.g. zinc arsenide

- Stibine from antimonides, e.g. magnesium antimonide

- Silanes from some silicides (analogue of hydrocarbons, with number of silicon atoms corresponding to the silicide anion structure, sometimes more are produced from the same compound; e.g. silane, disilane and trisilane from decomposition of magnesium silicide)

- Germanes from germanides, e.g. magnesium germanide

- Stannanes from stannides, e.g. magnesium stannide

- Boranes from borides (e.g. tetraborane from magnesium boride, aluminium boride, or beryllium boride and an acid)

- Hydrogen fluoride can be made from concentrated sulfuric acid and e.g. calcium fluoride

- Hydrogen bromide can be prepared from bromides with concentrated phosphoric acid (conc. sulfuric acid is too oxidizing)

A version of the apparatus can be used for reaction between two liquid precursors. A mercury trap has to be added as a check valve, and the middle bulb is filled with an inert porous material, e.g. pumice, onto which one of the precursors is dropped.[3]

- Hydrogen chloride is prepared from hydrochloric acid and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Hydrogen sulfide from concentrated sodium sulfide solution and diluted sulfuric acid

- Sulfur dioxide from 40% solution of sodium metabisulfite and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Nitric oxide from ferrous chloride in hydrochloric acid and 20% solution of sodium nitrite

- Dinitrogen trioxide, aka nitrous anhydride, from 20% solution of sodium nitrite and concentrated sulfuric acid

- Carbon monoxide, from concentrated formic acid and concentrated sulfuric acid.

Further gas treatments

[edit]The prepared gas is usually impure, contaminated with fine aerosol of the reagents and water vapor. The gases may need to be filtered, washed and dried before further use.

Hydrogen can be washed from sulfane, arsine and oxygen with subsequent bubbling through solutions of lead acetate, silver nitrate, and alkaline pyrogallic acid.[4]

Acidic gases (e.g. hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen chloride, sulfur dioxide) can be dried with concentrated sulfuric acid, or with phosphorus pentoxide. Basic gases (e.g. ammonia) can be dried with calcium oxide, sodium hydroxide or soda lime.

Disposal of the gases can be done by burning the flammable ones (carbon monoxide, hydrogen, hydrocarbons), absorbing them in water (ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, chlorine), or reacting them with a suitable reagent.[2]

Variants

[edit]Many variants of the gas production apparatus exist. Some are suitable for production of larger amounts of gases (Gay-Lussac and Verkhovsky), some for smaller amounts (Kiryushkin, U-tube).

A Döbereiner's lamp is a small modified Kipp's apparatus for production of hydrogen. The hydrogen is led over a platinum sponge catalyst, where it reacts with air oxygen, heats the catalyst and ignites from it, producing a gentle flame. It was commercialized for lighting fires and pipes. It's said that in 1820s over a million of the "tinderboxes" ("Feuerzeug") was sold.[5]

Further reading

[edit]- Griffin, John Joseph (1860). Chemical Recreations: A Popular Manual of Experimental Chemistry (10 ed.). John Joseph Griffin. p. 616. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

kipp's apparatus.

- Sella, Andrea (November 2007). "Kipp's Apparaatus". Chemistry World: 81. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Kipp's apparatus - extensive explanation with pictures and references

References

[edit]- ^ a b Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 267–. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ a b László Erdey (22 October 2013). Gravimetric Analysis: International Series of Monographs in Analytical Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 221–. ISBN 978-1-4832-2259-2.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on 2016-12-25.

- ^ Dunn, C. L.; Pandya, D. D. (2013-10-22). The Chemistry and Bacteriology of Public Health. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9781483195537.

- ^ Thomas, John Meurig; Thomas, W. John (February 2015). Principles and Practice of Heterogeneous Catalysis (Google Books) (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9783527314584.