Obadiah of Bertinoro

Obadiah ben Abraham of Bertinoro | |

|---|---|

| Personal life | |

| Born | c. 1450 (?)[1][2] |

| Died | c. 1516 (?) or before[1][2] |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

Obadiah ben Abraham of Bertinoro (Hebrew: ר׳ עוֹבַדְיָה בֵּן אַבְרָהָם מִבַּרְטֵנוּרָא; c. 1445 – c. 1515), commonly known as "The Bartenura", was a 15th-century Italian rabbi best known for his popular commentary on the Mishnah. In his later years, he rejuvenated the Jewish community of Jerusalem and became recognised as the spiritual leader of the Jews of his generation.[3]

Biography

[edit]In an Italian municipal document, his name is recorded as "Maestro Servadio di Habramo da Bertinoro", with Serviado being a translation of Ovadiah and Habramo a transliteration of Abraham (his father's name).[4] He was also known by the Hebrew acronym יר"א (Yareh).[4]

Obadiah was a student of Joseph Colon Trabotto[5] and became rabbi in Bertinoro, a town in the modern province of Forlì-Cesena, whence he derived his by-name, and in Castello.[6]

In Israel

[edit]The desire to visit the Holy Land led him to Jerusalem, and he arrived there on March 25, 1488, having commenced his journey on October 29, 1486. At the time, the Jewish community in Jerusalem was suffering greatly from oppressive levels of taxation, which led to suffering and emigration.[6]

In a letter written to his brother from Jerusalem on 24 August 1489, Obadiah mentions that Jews flock to Jerusalem from Egypt, Damascus, Aleppo, and other places to worship God. During that same year he says that he also met Jews from Aden. He says of himself that he was living in the home of the nagid, and that he gives regular sermons in a synagogue twice a month to the Jewish community, in the Hebrew language, and that he was exempt from paying the customary tax assessed to all other Jewish citizens.[7] He succeeded in obtaining a reduction in taxation levels from the government and supported the Jewish poor using his wealth from Italy.[6] On 17 December 1489, he writes that he had moved to Hebron where he found the atmosphere much more conducive and a small Jewish community numbering 20 households who were of a better temperament than those in Jerusalem, and where they lived along one alleyway.[8]

Bertinoro's personality, eloquence, and great reputation as a scholar led to his being accepted as the community's spiritual head immediately upon his arrival. His first care was to raise the intellectual plane of the community, and for this purpose, he interested the younger generation in the study of the Talmud and rabbinic literature, and he delivered sermons every other Shabbat in Hebrew.[6]

Upon the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, many exiles settled in Jerusalem, and Bertinoro became their intellectual leader. These Spanish Jews, more educated than the Musta'arabi Jews of Israel, presented Bertinoro with a site for a yeshiva in Jerusalem, which he founded, centuries after the extinction of the last academy in Israel. The Jews of Egypt and Turkey supported the maintenance of the yeshiva at Bertinoro's written solicitation. Isaac b. Nathan ibn Shulal, the nagid of Egypt, was especially helpful.[6]

In the decade during which Bertinoro thus controlled the best interests of the Jewish community at Jerusalem, a radical change for the better developed. Shortly after his arrival, he had been compelled upon one occasion to dig a grave because the community had provided no one to perform that labour; a few years later, the community enjoyed the benefits of hospitals, charitable relief societies, and similar associations. His reputation spread widely; not only was he accepted as a rabbinical authority, but the Muslim population frequently asked him to decide judicial cases.

He harshly reproved the rabbis for exacting fees for services at weddings and divorces, believing it their duty to perform religious ceremonies without monetary compensation.[6]

Works

[edit]Religion

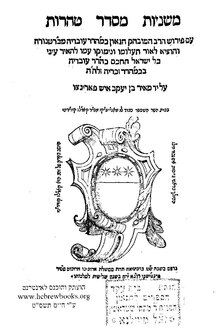

[edit]Bertinoro is best known as the primary commentator of the Mishnah; since its appearance (Venice, 1549) hardly an edition of the Mishnah has been printed without it.[6] The commentary is based mainly on Rashi and Maimonides.[6][4] Dedicated Mishnah study had been a marginal phenomenon in Jewish communities for many centuries; the few commentaries that were published tended to be limited to the tractates not covered by the Talmud, while Maimonides' commentary was written in Judeo-Arabic and thus inaccessible to many Jewish communities. Such study grew vastly in popularity in the late 16th century, aided by the spread of Bertinoro's accessible Hebrew Mishnah commentary.[4]

Bertinoro also authored a supercommentary upon Rashi's Pentateuch commentary. It was later published under the name Amar Nakeh (from Daniel 7:9);[9] but this title was given by a later printer rather than Bertinoro himself.[4]

Some piyyutim by Bertinoro exist in manuscript.[10][6]

Travel

[edit]He also wrote descriptions of his travels; and his letters to his relations in Italy, although intended only as private communications, are of great historical value. Most interesting in these letters[11] is the wealth of information concerning the social and intellectual conditions of the Jews in Greece, Egypt, and Israel. He shows himself not only a close observer, but a conscientious and unprejudiced chronicler. For example, he studied attentively the conditions of the Karaites in Alexandria, and did not hesitate to praise them for the possession of the very virtues which the Rabbanites denied to them, such as generosity and liberality.[12] His description of the Samaritans in Egypt[13] is one of the most valuable and reliable of medieval times."[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Obadiah of Bertinoro". Britannica online. Accessed 1 Aug 2022.

- ^ a b Bertinoro, Obadiah (1450?-1516?) (in French) at IdRef - Identifiants et Référentiels pour l'ESR. Agence bibliographique de l'enseignement supérieur. Accessed 1 Aug 2022.

- ^ Israel Zinberg (1978). "Spanish Exiles in Turkey and Palestine". A History of Jewish Literature: The Jewish center of culture in the Ottoman empire. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-87068-241-4. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Coffee with the Bartenura

- ^ Maharik, Responsa, No. 70, ed. Venice, 62a

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ginzberg (1906) in Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Igros Eretz Yisroel (Letters of the Land of Israel), in the "Letter of Rabbi Obadiah di Bertinora from Jerusalem to his Brother," written in 1489, Tel-Aviv 1943, pp. 140 Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine–141 (in PDF).

- ^ Iggerot Eretz Yisroel (Letters of the Land of Israel), in the "Letter of Rabbi Obadiah Jaré di Bertinora from Hebron," Tel-Aviv 1943, pp. 142–143 (Hebrew).

- ^ Pisa, 1810; reprinted in the collective work "Rabbotenu Ba'ale ha-Tosafot," Warsaw, 1889

- ^ Bodleian Library, Oxford (Nos. 1061; 2266, 6); in the first the name of his father is mentioned

- ^ First published by S. Sachs in the "Jahrbuch für Geschichte der Juden," 1863, iii. 195-224

- ^ l.c. p. 208; the text is to be emended according to the manuscript mentioned in Steinschneider, "Hebr. Bibl." vi. 131

- ^ l.c. pp. 206–208

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Bertinoro, Obadiah (Yareh) b. Abraham (called also Bartinoro)". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Bertinoro, Obadiah (Yareh) b. Abraham (called also Bartinoro)". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Further reading

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 813.