Upiór

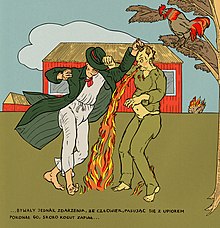

Illustration of Upiór | |

| Grouping | Male legendary creatures |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Slavic paganism |

| First attested | In folklore |

| Other name(s) | Ukrainian: Упир |

Upiór (Tatar language: Убыр (Ubır), Turkish: Ubır, Obur, Obır, (modern Belarusian: вупыр (vupyr), Bulgarian: въпир(văpir), Serbian: вампир (vampir), Czech and Slovak: upír, Polish: upiór, wupi, Russian: упырь (upyr'), Ukrainian: упир(upyr), from Old East Slavic: упирь (upir'))) is a demonic being from Slavic and Turkic folklore, a prototype of the vampire.[1] It is suggested that the ubır (upiór) belief spread across the Eurasian steppes through the migrations of the Kipchak-Cuman people, after having its origins in the regions surrounding the Volga (İtil) River and the Pontic steppes. The modern word "vampire" derives from the Old Slavic language and Turkic form онпыр (onpyr), with the addition of the sound "v" before a large nasal vowel (on), characteristic of Old Bulgarian, as evidenced by the traditional Bulgarian form впир (vpir). (other names: onpyr, vopir, vpir, upir, upierz.)[2]

Etymology

This section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (November 2021) |

The exact etymology is unclear. Among the proposed proto-Slavic forms are ǫpyrь and ǫpirь.[3] Another, less widespread theory, is that the Slavic languages have borrowed the word from a Turkic term for Ubır or Ubar 'witch, vampire, hortdan'.[4] Czech linguist Václav Machek proposes the Slovak verb vrepiť sa ('stick to, thrust into'), or its hypothetical anagram vperiť sa (in Czech, the archaic verb vpeřit means 'to thrust violently') as an etymological background, and thus translates upír[what language is this?] as 'someone who thrusts, bites'.[5]

An early use of the Old East Slavic word is in the anti-pagan treatise "Word of Saint Grigoriy" (Russian Слово святого Григория), dated variously to the 11th–13th centuries, where pagan worship of upyri is reported.[6][7]

The term upiór (upir – Proto-Slavic language *ǫpirь, OCS ǫpyrь/ѫпырь) was introduced to the English-language culture as a "vampyre", mentioned by Lord Byron in The Giaour in 1813, described by John William Polidori in "The Vampyre" in 1819, and popularised by Bram Stoker's Dracula. With the development of mass culture, he returned as a "vampire" recognizable in literature and film.[8] In Slavic folk culture, the upiór has features that are strongly present in strzyga,[9] and so Adam Mickiewicz has theorized upiór developed from an ancient Roman and Greek strix.[10] In Ukraine (e.g. in the Chigirinsky Uyezd), the term martvyets was used to describe the upiór.[11]

In Slavic culture

Common Slavic belief indicates a stark distinction between soul and body. The soul is not considered to be perishable. The Slavs believed that upon death the soul would go out of the body and wander about its neighbourhood and workplace for 40 days before moving on to an eternal afterlife. Thus pagan Slavs considered it necessary to leave a window or door open in the house for the soul to pass through at its leisure. During this time the soul was believed to have the capability of re-entering the corpse of the deceased. Much like the spirits mentioned earlier, the passing soul could either bless or wreak havoc on its family and neighbours during its 40 days of passing. Upon an individual's death, much stress was placed on proper burial rites to ensure the soul's purity and peace as it separated from the body. The death of an unbaptized child, a violent or an untimely death, or the death of a grievous sinner (such as a sorcerer or murderer) were all grounds for a soul to become unclean after death. A soul could also be made unclean if its body were not given a proper burial. Alternatively, a body not given a proper burial could be susceptible to possession by other unclean souls and spirits. Slavs feared unclean souls because of their potential for taking vengeance.[12]

From these deep beliefs pertaining to death and the soul derives the invention of the Slavic concept of Ubır. A vampire is the manifestation of an unclean spirit possessing a decomposing body. This undead creature needs the blood of the living to sustain its body's existence and is considered to be vengeful and jealous towards the living. Although this concept of vampire exists in slightly different forms throughout Slavic countries and some of their non-Slavic neighbours, it is possible to trace the development of vampire belief to Slavic spiritualism preceding Christianity in Slavic regions.

Folk beliefs

Origin, appearance, and activity of the upiór

An upiór was a person cursed before death,[13] a person who died suddenly, or someone whose corpse was desecrated. Other origins included a dead person over whom an animal jumped, suicide victims,[13][14] witches, unchristened children, and those who were killed by another upiór.[15][16]

It was believed that those who were physically different in a community were potential upiór candidates: redheads, the left-handed, those with a limp, unibrow, a double set of teeth[17] or with a gray mark on their back[18] and religiously "other" (e.g. Lutherans in Catholic communities).[8] Suspicious traits among the living also included walking by moonlight, having a big head, or no armpit or pubic hair.[19]

Many of these ideas are reproduced in the legends and ethnographic records of strzygas,[17] and upiórs are often described as having two hearts and two souls, just like strzygas.[18]

Women who died during or after childbirth were particularly vulnerable to the transformation. It was feared that they would return to the orphaned child as upiórs to feed it at night. That is why in Silesia, for example, those who died in childbirth were buried by the edge of the cemetery, near the wall.[20]

Lack of rigor mortis, a flushed face or blood beneath the nails were signs that a deceased person could become an upiór/wąpierz. The signs of its misdeeds among family or neighbours could be fatigue, pallor, sweating, or recurring nightmares.[8][13] A upiór could haunt its family if the family burned the photograph or portrait of the deceased.[14] A dead person buried in an old shirt could also become an upiór.[20]

One way to recognize an upiór was to have an innocent child ride a horse to a cemetery and have them indicate the grave of the upiór.[18] A upiór could be seen in the mirror in the evening, so in the Sieradz region, people would not look into mirrors after dusk.[20]

Upiórs arrived at night, carrying their heads in their arms, or, if the head was not detached, with glowing "wolf-like" eyes.[21][11] Some of them caused menace during daytime, climbing up bell towers and killing everyone who heard their shriek.[16]

Upiórs drank human blood, and used their superhuman strength to tear their victims to shreds. They could also kill with their breath or shrieks.[16] They harassed people at night, making them suffocate or sleepwalk. There were claims of husbands and wives becoming upiórs and visiting the widowed spouse after death. They would do the chores they did during lifetime, and sometimes harass the family.[11][8]

Cattle and human plagues were often blamed on witches or upiórs, causing the communities to accuse and lynch innocent people.[10]

Remedies against upiórs

It was said that the dead should be taken out of the house through a special exit or hole, because if they were taken out via the main door they could become upiórs.[14]

Dead people thought to be upiórs had garlic heads, bricks, or iron chunks placed in their mouths before burial.[20] Branches of wild rose, hawthorn, or blackthorn were put into their coffins. The coffins were sprinkled with poppy-seed, so the upiórs would have a chore (picking all the seeds up) to occupy them.[20] Another method of keeping the upiórs busy was to give them little knots or nets or other small things to untangle in the grave (Pomerania).

If a person thought to be an upiór died, or if someone's grave was believed to be an upiór's grave, a vampire burial was performed. The head could be cut off and put between the legs of the corpse,[10] the corpse could be burned,[18] nailed to the coffin,[10] or repositioned to lie face-down.

If an upiór harassed a human at night, the remedy was to stop the upiór returning to its grave - at dawn it would disappear or change into black tar.[8][21] Another protective measure was to drink the upiór's blood or eat soil off its grave.[18]

Local variations

- Near Słupia, a young man who committed suicide due to unrequited love was thought to be an upiór. After burying him in a secluded hole, the upiór supposedly appeared and attacked people and cattle. It disappeared when the rooster called at dawn.[21]

- Near Warsaw, a body found on the road was treated as a potential upiór, and branches were thrown over it. In spring, those stacks of branches were burned, so that the soul of the dead underneath would be purged of its sins.[16]

- Near Kraków, a way to free an upiór's soul was recorded in 1847: one was supposed to stake the upiór's head with a nail, and then put paper with writings by a teacher/professor underneath its tongue. Then a priest would be asked to cut the upiór's head and reposition it face-to-the-pillow in the coffin.[18]

- In Liszki village, a story was told about a woman who found an upiór in one of three coffins at night. She cut its liver out to make a meal for her husband. The upiór later harassed the family until they fell ill and died.

- In Lubelskie, the dead were buried face-down with hands tied with blessed herbs to prevent them from becoming upiórs.[20]

- In Pokuttia, a Ruthenian woman who was said to be "loved by an upiór" was taken out of her house after her death via a hole made in a wall, and then buried at the crossroads, in accordance with her wishes.[14]

- In Volhynia, housewives baking bread would cover the ovens, so that they "would not die with open mouth", which would cause them to "become a man-eating everyone".[14]

- A story from Ukrainian farmers from Chigirinsky Uyezd was recorded, about an upiór who protected a Cossack from a hangman.[11]

- A story from a 1701 journey to Mykonos described a days-long fight between the locals and an upiór. The deceased man supposedly entered houses, threw candles, and scared families so that they would sleep outside. His heart was taken out and burned by the sea, and when this measure combined with prayers did not help, the exhumed body was burned entirely.[18]

- Near Gradiška until the end of the 19th century, a story was told about a dead father haunting his son and asking for food. After one visit, six family members fell sick and died. After a commission examined the body and decided it looked unusual, the father was deemed an upiór. The heart was staked, and the body burnt.[18]

In Turkish culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

The ubir (Chuvash: Вупăр (Vupăr) or Вупкăн (Vupkăn), Tatar: Убыр, Turkish: Ubır) of Turkic mythology is a mythological or folkloric being very similar to the Slavic upiór. Ubirs subsist by feeding on the life essence (generally in the form of blood) of living creatures, regardless of whether it is an undead person or being.

Ubirs were usually reported as bloated in appearance, and ruddy, dark in colour; these characteristics were often attributed to the recent drinking of blood. The causes of vampiric generation were many and varied in original folklore. Ubirs are reanimated corpses that kill living creatures to absorb life essence from their victims.

Tales of supernatural beings consuming the blood or flesh of the living have been found in nearly every culture around the world for many centuries. Almost every nation has associated blood drinking with some kind of revenant or demon, or in some cases a deity. A story is told about blood drinking in the Epic of Ural-Batyr. Once, when the parents were gone hunting, Shulgen challenged Ural to drink the blood of an animal left by their parents at home. [22] Ural refused to do it, and Shulgen drank the blood himself. Their parents cursed their son Shulgen and rejected him.

See also

References

- ^ Jarosław Kolczyński (2003). "Jeszcze raz o upiorze (wampirze) i strzygoni (strzydze)". Etnografia Polska. 1–2.

- ^ Yaltırık, Mehmet Berk; Sarpkaya, Seçkin (2018). Turkish: Türk Kültüründe Vampirler, English translation: Vampires in Turkic Culture (in Turkish). Karakum Yayınevi. pp. 43–49.

- ^ "Russian Etymological Dictionary by Max Vasmer" (in Russian). Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- ^ (in Bulgarian)Mladenov, Stefan (1941). Etimologičeski i pravopisen rečnik na bǎlgarskiya knižoven ezik.

- ^ MACHEK, V.: Etymologický slovník jazyka českého, 5th edition, NLN, Praha 2010

- ^ Рыбаков Б.А. Язычество древних славян / М.: Издательство 'Наука,' 1981 г. (in Russian). Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ Зубов, Н.И. (1998). Загадка Периодизации Славянского Язычества В Древнерусских Списках "Слова Св. Григория ... О Том, Како Первое Погани Суще Языци, Кланялися Идолом...". Живая Старина (in Russian). 1 (17): 6–10. Archived from the original on 2007-02-25. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ a b c d e Jarosław Kolczyński (2003). "Jeszcze raz o upiorze (wampirze) i strzygoni (strzydze)". Etnografia Polska. 1–2.

- ^ Strzelczyk, Jerzy. (2007). Mity, podania i wierzania dawnych Słowian. Poznań: Rebis. ISBN 9788373019737. OCLC 228025091.

- ^ a b c d Adam Mickiewicz (1865). Literatura słowiańska: Wykładana w Kolegium francuzkiem przez Adama Mickiewicza. Poznań.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d A. Podbereski (1880). "Materiały do demonologii ludu ukraińskiego: z opowiadań ludowych w powiecie czehryńskim". Kraków.

- ^ Perkowski, "Vampires of the Slavs," pp. 21–25.

- ^ a b c Adam Mickiewicz (1823). Upiór.

- ^ a b c d e Henryk Biegeleisen (1929). U kolebki. Przed ołtarzem. Nad mogiłą. Lwów.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ L. Stomma (1986). Antropologia kultury wsi polskiej XIX w.

- ^ a b c d Oskar Kolberg (1970). "Dzieła Wszystkie – Lud..."

- ^ a b "Strzygoń/strzyga – Polska bajka ludowa. Słownik – red. Violetta Wróblewska". bajka.umk.pl. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Oskar Kolberg (1874). Lud: jego zwyczaje, sposób... Vol. t. VII -Krakowskie, cz. 3.

- ^ "Upiór – Polska bajka ludowa. Słownik – red. Violetta Wróblewska". bajka.umk.pl. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Adam Fischer (1921). "Zwyczaje pogrzebowe ludu polskiego".

- ^ a b c Oskar Kolberg (1964). "Lud..."

- ^ Ural Batyr- Variant English, Kuzbekova Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Cheung, Theresa: The Element Encyclopedia Of Vampires. Harper Collins Publishers, London 2009, ISBN 9780007312795

- Maiello, Giuseppe: Vampyrismus v kulturních dějinách Evropy. Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, Praha 2005, 190 s.

- Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythological Dictionary), Deniz Karakurt, (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)(in Turkish)

- Türk Mitolojisi Ansiklopedik Sözlük, Celal Beydili, Yurt Yayınevi (Page - 435) (in Turkish)

External links

- Upiri: od mrtvol k supermanům (in Czech)