Citadel of Erbil

| Erbil Citadel | |

|---|---|

Kurdish: قەڵای هەولێر | |

| Erbil, Kurdistan Region, Iraq | |

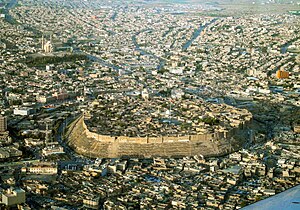

Aerial view of the Erbil citadel | |

| Coordinates | 36°11′28″N 44°00′32″E / 36.191°N 44.009°E |

| Type | Citadel |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Kurdistan Region |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Partially ruined |

| Site history | |

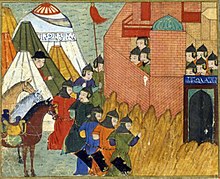

| Battles/wars | Siege by the Mongols (1258) |

| Official name | Erbil Citadel |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 2014 (38th session) |

| Reference no. | 1437 |

| Region | List of World Heritage Sites in Iraq |

The Erbil Citadel (Kurdish: قەڵای هەولێر Qelay Hewlêr, Arabic: قلعة اربيل, romanized: Qal'at Erbīl) locally called Qalat, is a tell or occupied mound, and the historical city centre of Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.[1] The citadel has been included in the World Heritage List since 21 June 2014.

The earliest evidence for occupation of the citadel mound dates to the 5th millennium BC, and possibly earlier. It appears for the first time in historical sources in the Ebla tablets in modern Syria around 2000 BC, and gained particular importance during the Neo-Assyrian period. During the Sassanian period and the Abbasid Caliphate, Erbil was an important centre for Christianity. After the Mongols captured the citadel in 1258, the importance of Erbil declined. During the 20th century, the urban structure was significantly modified, as a result of which a number of houses and public buildings were destroyed. In 2007, the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) was established to oversee the restoration of the citadel. In the same year, all inhabitants, except one family, were evicted from the citadel as part of a large restoration project. Since then, archaeological research and restoration works have been carried out at and around the tell by various international teams and in cooperation with local specialists. The government plans to have 50 families live in the citadel once it is renovated.

The buildings on top of the tell stretch over a roughly oval area of 430 by 340 metres (1,410 ft × 1,120 ft) occupying 102,000 square metres (1,100,000 sq ft). The only religious structure that currently survives is the Mulla Afandi Mosque. The mound rises between 25 and 32 metres (82 and 105 ft) from the surrounding plain. When it was fully occupied, the citadel was divided in three districts or mahallas: from east to west the Serai, the Takya and the Topkhana. The Serai was occupied by notable families; the Takya district was named after the homes of dervishes, which are called takyas; and the Topkhana district housed craftsmen and farmers.

History

Prehistory

The site of the citadel may have been occupied as early as the Neolithic period, as pottery fragments possibly dating to that period have been found on the slopes of the mound. Clear evidence for occupation comes from the Chalcolithic period, with sherds resembling pottery of the Ubaid and Uruk periods in the Jazira and southeastern Turkey, respectively.[2] Given this evidence for early occupation, the citadel has been called the oldest continuously occupied town in the world.[1][3]

Earliest historical records

Erbil appears for the first time in literary sources around 2300 BC in the archives of Ebla. According to Giovanni Pettinato, it is mentioned in two tablets as Irbilum.[4]

The city was first largely under Sumerian domination from c. 3000 BC, until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) which united all of the Akkadian Semites and Sumerians of Mesopotamia under one rule.

Later, Erridupizir, king of Gutium, captured the city in 2200 BC.[5]

At the end of the 3rd millennium BC, Erbil is mentioned in historical records of the Ur III period as Urbilum. King Shulgi destroyed Urbilum in his 43rd regnal year, and during the reign of his successor Amar-Sin, Urbilum was incorporated into the Ur III state. In the 18th century BC, Erbil appears in a list of cities that were conquered by Shamshi-Adad of Upper Mesopotamia and Dadusha of Eshnunna during their campaign against the land of Qabra. Shamshi-Adad installed garrisons in all the cities of the land of Urbil. During the 2nd millennium BC, Erbil was incorporated into Assyria. Erbil served as a point of departure for military campaigns toward the east.[6][7]

From the Neo-Assyrian period to the Sassanids

Erbil was an important city during the Neo-Assyrian period. The city took part in the great revolt against Shamshi-Adad V that broke out over the succession of Shalmaneser III. During the Neo-Assyrian period, the name of the city was written as Arbi-Ilu, meaning 'Four Gods'. Erbil was an important religious centre that was compared with cities such as Babylon and Assur. Its goddess Ishtar of Erbil was one of the principal deities of Assyria, often named together with Ishtar of Nineveh. Her sanctuary was repaired by the kings Shalmaneser I, Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. Inscriptions from Assurbanipal record oracular dreams inspired by Ishtar of Erbil. Assurbanipal probably held court in Erbil during part of his reign and received there envoys from Rusa II of Urartu after the defeat of the Elamite ruler Teumman.[6]

After the end of the Assyrian Empire, Erbil was first controlled by the Medes and then incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire before it became part of the empire of Alexander the Great after the Battle of Gaugamela, which was fought near Erbil in 331 BC.[8] Subsequently, after the partition of Alexander the Great's Empire by his generals (known as Diadochoi), the city was called Arabella or Arbela and it was part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Kingdom. After the 1st century BCE, the Roman and Parthian Empire fought over control of Erbil, or Arbira as it was known in that period. After the 1st century AD, Arbela became an important Christian center. During the Sassanid period, Erbil was the seat of a satrap (governor). In 340 AD, Christians in Erbil were persecuted and in 358, the governor became a martyr after he converted to Christianity.[9] A Nestorian school was founded in Erbil by the School of Nisibis in c. 521.[10] During this period, Erbil was also the site of a Zoroastrian fire temple.[11]

Muslim conquest until the Ottomans

Erbil was conquered by the Muslims in the 7th century. It remained an important Christian center until the 9th century, when the bishop of Erbil moved his seat to Mosul. In the middle of the 10th century, Erbil came under the rule of Hadhabani Kurds until 1063 when it was taken over by the Seljuks. From the first half of the 12th century until 1233, Erbil was the seat of the Begteginids, a Turcoman dynasty that rose to prominence under the reign of Zengi, the atabeg of Mosul. In 1183, Zain ad-Din Yusuf, ruler of Erbil, shifted his allegiance to the Ayyubid Sultanate. In 1190 when Zain ad-Din Yusuf died, his older brother Muzaffar al-Din Gökböri, who was previously governor of Edessa, became the new governor of Erbil. He created a lower town around the city on the citadel mound and founded hospitals and madrasahs. When Gökburi died in 1233 without an heir, control of Erbil shifted to the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustansir after he had besieged the city.[9][12]

When the Mongols invaded the Near East in the 13th century, they attacked Erbil for the first time in 1237. They plundered the lower town but had to retreat before an approaching caliphal army and had to put off the capture of the citadel.[13] After the fall of Baghdad to Hülegü and the Mongols in 1258, they returned to Erbil and were able to capture the citadel after a siege lasting six months.[14] Hülegü then appointed a Christian governor to the town and there was an influx of Jacobite Christians, who were allowed to build a church.

As time passed, persecutions of Christians, Jews and Buddhists throughout the Ilkhanate began in earnest in 1295 under Oïrat amir Nauruz.[15] This manifested early on in the reign of the Ilkhan Ghazan. In 1297, after Ghazan had felt strong enough to overcome Nauruz' influence, he put a stop to the persecutions.

During the reign of the Ilkhan Öljeitü some of the Christian inhabitants retreated to the citadel to escape persecution. In the spring of 1310, the Malek (governor) of the region attempted to seize it from them with the help of the Kurds. Despite Mar Yahballaha's best efforts to avert the impending doom, the citadel was at last taken by Ilkhanate troops on 1 July 1310, and all the defenders were massacred, as were all the Christian inhabitants of the lower town.[9][16]

After Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, Erbil came under control of Soran emirate, a semi-independent Emirate under the Ottomans. In the 18th century Baban Emirate took the city but it was retaken by Soran ruler Mir Muhammed Kor in 1822. The Soran emirate continued ruling over Erbil until it was retaken by the Ottomans in 1851. Erbil became part of the Musul Vilayet in Ottoman Empire until World War I, when the Ottomans were defeated by the British Empire. The town had approximately 3,200 inhabitants, including a sizeable Jewish minority.[3]

Modern period

During the 20th century, the citadel witnessed significant urban and social changes. A 15-metre (49 ft) high steel water tank was erected on the citadel in 1924, providing the inhabitants with purified water, but also causing water damage to the foundations of the buildings due to increased water seepage. The number of inhabitants gradually declined over the 20th century as the city at the foot of the citadel grew and wealthier inhabitants moved to larger, modern houses with gardens.[17] In 1960, over 60 houses, a mosque, and a school were demolished to make way for a straight road connecting the southern gate with the northern gate.[18] Some reconstruction works were carried out in 1979 on the citadel's southern gate and the hammam. In 2007, the remaining 840 families were evicted from the citadel as part of a large project to restore and preserve the historic character of the citadel. These families were offered financial compensation. One family was allowed to continue living on the citadel to ensure that there would be no break in the possible 8,000 years of continuous habitation of the site, and the government plans to have 50 families live in the citadel once its renovated.[19] In 2004, the Kurdish Textile Museum opened its doors in a renovated mansion in the southeast quarter of the citadel.[20]

The Citadel and the Bazaar

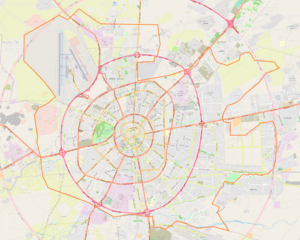

The city of Erbil is defined by the central circular mound that is the citadel, 102,000 square metres of land raised 26 metres above the surrounding city, presumed to have been started in antiquity as a tell. Around and beneath it to the south sprawl a maze of alleyways where the ancient commercial heart of the city beats strongly to this day. The citadel dwellings still stand, although they are now vacated as part of the UNESCO development project to renovate the buildings. Former resident Mahmoud Yasim, who grew up with his seven siblings in the 8000-year-old network of alleyways alongside some 830 other families, describes the community they enjoyed: 'Everyone used to know each other back then. We were living in houses without permission and they were very old and partially collapsed – but our lives were good. We were close to everything – the bazaar, the hospital and schools as well.' A great many of the inhabitants were sad to leave when the authorities relocated them in 1997 – largely to Qalai New (the 'New Citadel') – but it has afforded the opportunity to start work on rebuilding the crumbling structures, restoring wherever possible the intricate plasterwork and distinctively carved lintels. The market area below is thought to have been created in the time of Sultan Muzafferddin Kokberi (1190–1233). This period, the only time in its long history when Erbil flourished as an independent city state, also saw the creation of the minaret recently restored in downtown Erbil, and was also the time when the Muzafferddin madrassahs (schools) were founded.

The area around the southern base of the citadel has received the attention of modern town planners, with the large open-air Lana market where once market stalls sold leather crafts now and replaced by a large modern shopping mall. The covered market, known as Qasariyah, still stands largely unchanged: A labyrinth of small alleyways protected from sun and rain by a latticework of corrugated iron. Beneath these eaves are the numerous shopkeepers selling wares largely imported from the Far East interspersed with craftsmen plying a trade they inherited from their forefathers in the late nineteenth century when the bazaar was restored: Jewellers, cobblers, carpenters, tinsmiths and butchers. Where possible, tradesmen gather alongside others who trade in the same wares, giving each alleyway a specialism such as the passageway towards the north-east corner where honey and dairy products are sold – yoghurts and cheeses piling the highly valued local honey. Another highly prized tradition is the creation of Klash shoes – an ancient uniquely Kurdish craft when white cloth is beaten on small anvils to create hardwearing footwear. These, and the traditional fabrics sold in the textile souk, are ever-popular in the run-up to the annual Newroz celebrations when the townspeople assume traditional attire.[21]

Architecture and layout

The citadel is situated on a large tell – or settlement mound – of roughly oval shape that is between 25 and 32 metres (82 and 105 ft) high. The area on top of the mound measures 430 by 340 metres (1,410 ft × 1,120 ft) and is 102,000 square metres (1,100,000 sq ft) large. Natural soil has been found at a depth of 36 metres (118 ft) below the present surface of the mound.[22] The angle of the citadel mound's slopes is c. 45°.[3] Three ramps, located on the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the mound, lead up to gates in the outer ring of houses. The southern gate was the oldest and was rebuilt at least once, in 1860, and demolished in 1960. The current gate house was constructed in 1979. The eastern gate is called the Harem Gate and was used by women. It seems unclear when the northern gate was opened. One source claims that it was opened in 1924,[17] while another observes that there were only two gates in 1944 – the southern and eastern gates.

During the early 20th century, there were three mosques, two schools, two takyas and a hammam on the citadel.[23] The citadel also housed a synagogue until 1957.[22] The only religious structure that currently survives is the Mulla Afandi Mosque, which was rebuilt on the location of an earlier 19th-century mosque.[24] The hammam was built in 1775 by Qassim Agha Abdullah. It went out of service during the 1970s and was renovated in 1979, although many original architectural details were lost.[22][25]

When it was still occupied, the citadel was divided in three districts or mahallas: from east to west the Serai, the Takya and the Topkhana. The Serai was occupied by notable families; the Takya district was named after the homes of dervishes, which are called takyas; and the Topkhana district housed craftsmen and farmers. A 1920 inventory showed that at that time the citadel was divided into 506 house plots. Since then the number of houses and inhabitants has gradually declined. For example, in 1984 4,466 people lived in 375 houses, whereas a 1995 census showed that the citadel had only 1,631 inhabitants living in 247 houses.[23] Until the opening-up of the main north–south thoroughfare, the streets on the citadel mound radiated outward from the southern gate like the branches of a tree. Streets were between 1 and 2.5 metres (3 ft 3 in and 8 ft 2 in) wide and ranged in length from 300 metres (980 ft) for major alleyways to 30–50 metres (98–164 ft) for cul-de-sacs.[26]

The perimeter wall of the citadel is not a continuous fortification wall, but consists of the façades of approximately 100 houses that have been built against each other. Because they have been built on or near the steep slope of the citadel mound, many of these façades were strengthened by buttresses to prevent their collapse or subsidence.[27] There were circa 30 city-palaces; most of them located along the perimeter of the citadel.[28] The oldest surviving house that can be securely dated through an inscription was built in 1893. The oldest houses can be found on the southeastern side of the mound, whereas houses on the northern perimeter date to the 1930s–1940s.[29][30] Before the introduction of modern building techniques, most houses on the citadel were built around a courtyard. A raised arcade overlooking the courtyard, a flat roof and a bent-access entrance to prevent views of the courtyard and the interior of the house were characteristic elements of the houses on the citadel.[28]

Research and restoration

In 2006 and 2007, a team from the University of West Bohemia, together with Salahaddin University in Arbil, carried out an extensive survey and evaluation of the entire citadel. As part of this project, geodetic measurements of the citadel were taken and these were combined with satellite imagery, regular photographic imagery and aerial photographs to create a map and digital 3D model of the citadel mound and the houses on top of it. Geophysical prospection was carried out in some areas of the citadel to detect traces of older architecture buried under the present houses. Archaeological investigations included an archaeological survey on the western slope of the citadel mound, and the excavation of a small test trench in the eastern part of the citadel.[31]

in 2012, the Higher Committee for the Maintenance and Rehabilitation of the Erbil Citadel decided to identify seven areas inside the Citadel to conduct excavations, and to search for the remains of the wall and the historical fortifications of the citadel, the commission chose point E because it is on the northwest edge of the citadel, west of the main gate (Bab Ahmadi), which facilitated the process of finding the historic wall of the citadel. The excavations took place in four seasons 2013-2014-2015 under the chairmanship of Dr. Abdullah Khurshid and many foreign consultants, including Dr. John McCains from Cambridge University in Britain. A part of the citadel wall of Erbil has been discovered, which was not visible, we didn't know much about it only passing references in historical writings, which mentions that the wall was surrounding the citadel, which enabled the inhabitants of the citadel to defend it against the attacks of enemies and invaders.[32]

A Neo-Assyrian chamber tomb was found at the foot of the citadel mound during construction activities in 2008. It was subsequently excavated by the local Antiquities Service and archaeologists from the German Archaeological Institute (DAI). The tomb was plundered in antiquity but still contained pottery dating to the 8th and 7th centuries BC.[33] The cooperation between the Antiquities Service and the DAI was continued later that year with a further investigation of the tomb and with a small excavation nearby and geophysical survey of the surrounding area, in which also students from Salahaddin University participated. These investigations revealed the presence of architecture probably dating to the Neo-Assyrian period, as well as more burials belonging to subsequent centuries.[34]

In 2007, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) established the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) to preserve and restore the citadel with the help of UNESCO.[1] Among other things, the HCECR advocates the establishment of a zone extending up to 300–400 metres (980–1,310 ft) from the citadel in which building height should be restricted to approximately 10 metres (33 ft). This would ensure the visual dominance of the citadel over its surroundings.[35]

On 2 April 2019, NASA has described the historic citadel as possibly the oldest continuously occupied human settlement on Earth.[36][37]

UNESCO World Heritage status

On 8 January 2010, the HCECR and the Iraqi State Board for Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) submitted the Citadel of Erbil to the Iraqi Tentative List of sites that are considered for nomination as World Heritage Site. The submission states that "The Citadel is today one of the most dramatic and visually exciting cultural sites not only in the Middle East but also in the world."[1] Two further agreements between the HCECR and UNESCO were signed in March 2010, and it was disclosed that Arbil Governorate will finance the restoration project with US$13 million.[38] The first restoration works were carried out in June 2010.[39] The Citadel was inscribed on the World Heritage List on 21 June 2014. In January 2017, UNESCO indicated that the site could be removed from the list due to the slow progress being made in the restoration program.[40]

Places to visit at the Citadel

- The Kurdish Textile and Ethnographic (Cultural) Museum

- The French Institute of the Near East (French: Institut français du Proche-Orient, IFPO)

- Erbil Citadel Cultural Center

- Traditional Hammam (public bath)

- Great Mosque (Mulla Effendi Mosque)

- Erbil Stones and Gems Museum

- Citadel Antiques (souvenirs)

- High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR), head office

- Turkmen Heritage House

- Exhibition of Miniature of Kurdistan Costumes

- Kurdistan Music Archive

- Kurdish Tourism Association

- Barzani Museum

- Erbil Citadel Visitor Center

- Erbil Citadel Interpretation Center

- Exhibition of Handmade Carpets

- Mulla Ibrahim Dogramachi Mosque

-

Erbil Citadel Visitor Center

-

Kurdish Textile and Ethnographic (Cultural) Museum

-

The French Institute of the Near East

-

Exhibition of Miniature of Kurdistan Costumes (left) and Kurdistan Music Archive (right)

-

A panoramic photo of Erbil Citadel

-

Gate street

Gallery

Some photos of the Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work, 2014.

-

An alley, Citadel of Erbil, during the restoration work in 2014

-

Citadel during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Citadel of Erbil during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Wall of the Citadel during the restoration work in 2014. Hawler, Erbil, Kurdistan Region.

-

Courtyard in a traditional house in Erbil Citadel.

-

Courtyard in a traditional house in Erbil Citadel.

-

Ornaments and details in a traditional house in Erbil Citadel.

-

Ornaments and details in a traditional house in Erbil Citadel.

-

A balcony in a traditional house in Erbil Citadel with ornamented hand-railing.

-

Erbil Citadel wall

-

Dilapidated old houses around the Citadel

-

Old houses around the Citadel

-

Dilapidated old houses around the Citadel

-

Old houses around the Citadel

-

Old houses around the Citadel

-

One of the houses around Erbil Citadel

References

- ^ a b c d "Erbil Citadel – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 276

- ^ Martha A. Morrison, David I. Owen, eds, General Studies and Excavations at Nuzi 9/1; Volume 2 In Honor of Ernest R. Lacheman. Eisenbrauns, 1981 ISBN 0931464080

- ^ Timeline Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine ErbilCitadel.orq

- ^ a b Villard 2001

- ^ Eidem 1985, p. 83

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 260

- ^ a b c Sourdel 2010

- ^ Morony 1984, p. 359

- ^ Morony 1984, p. 132

- ^ Cahen 2010

- ^ Woods 1977, pp. 49–50

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 261

- ^ Grousset, p. 379

- ^ Grousset, p. 383

- ^ a b "History". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Historical Evolution". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Qassim Khidhir Hamad. "The pride of erbil needs urgent care". niqash.org. Archived from the original on 8 May 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Ivan Watson. "Kurds Displaced in Effort to Preserve Ancient City". NPR. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Fryer, Jonathan (2010). Kurdistan. London: Stacey international. p. 16.

- ^ a b c Nováček et al. 2008, p. 262

- ^ a b "Mahallas". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "The Mosque". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "The Hammam". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Alleyways". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Perimeter Wall". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Houses". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE 01". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Urban Growth". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008

- ^ Sherko, Jehan. "Erbil Citadel and Its Lost Wall". Academia.edu. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Kehrer 2009

- ^ Kehrer 2010

- ^ "The Citadel & The City". erbilcitadel.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "NASA: Kurdistan's Erbil Citadel oldest human-occupied settlement on Earth". Kurdistan24.

- ^ "History on a Hill". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 1 April 2019.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Erbil Citadel". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ McDermid 2010

- ^ "Kurdistan's Erbil Citadel at risk of being removed from UNESCO World Heritage list". Ekurd.net. 21 January 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Sources

- Cahen, Cl. (2010), "Begteginids", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam (second ed.), Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Eidem, Jesper (1985), "News from the eastern front: the evidence from Tell Shemshāra", Iraq, 47: 83–107, doi:10.2307/4200234, ISSN 0021-0889, JSTOR 4200234

- Kehrer, Nicole (2009), "Deutsche Experten untersuchen assyrische Grabstätte in Arbil", Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (in German), archived from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 8 July 2010

- Kehrer, Nicole (2010), "Deutsche Archäologen arbeiten wieder im Irak", Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (in German), archived from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 8 July 2010

- McDermid, Charles (29 July 2010), "A Facelift for an Ancient Kurdish Citadel", Time, archived from the original on 31 July 2010, retrieved 2 August 2010

- Morony, Michael G. (1984), Iraq after the Muslim conquest, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-05395-0

- Naval Intelligence Division (1944), Iraq and the Persian Gulf, Geographical Handbook Series, OCLC 1077604

- Nováček, Karel; Chabr, Tomáš; Filipský, David; Janiček, Libor; Pavelka, Karel; Šída, Petr; Trefný, Martin; Vařeka, Pavel (2008), "Research of the Arbil Citadel, Iraqi Kurdistan, First Season", Památky Archeologické, 99: 259–302, ISSN 0031-0506, retrieved 13 July 2010

- Sourdel, D. (2010), "Irbil", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam (second ed.), Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Villard, Pierre (2001), "Arbèles", in Joannès, Francis (ed.), Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Bouquins (in French), Paris: Robert Laffont, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-2-221-09207-1

- Woods, John E. (1977), "A note on the Mongol capture of Isfahān", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 36 (1): 49–51, doi:10.1086/372531, ISSN 0022-2968, JSTOR 544126

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Translated from the French by Naomi Walford), New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press (1970)

Further reading

- Nordland, Rod (10 October 2017). "After 6,000 Years of Human Habitation, One Family and Lots of Mice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

- Citadel of Arbil on the World Heritage List

- High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR)

- Citadel Documentation Project[permanent dead link]

- Research of the citadel at Arbil, Kurdistan Region

- Pictures of houses in the vicinity of Erbil Citadel

http://www.academia.edu/119028755/Pictures_of_houses_in_the_vicinity_of_Erbil_Citadel