Palais des Papes

| Palais des Papes | |

|---|---|

View from the Tour Philippe-le-Bel | |

| Location | Avignon, France |

| Coordinates | 43°57′03″N 4°48′27″E / 43.9508°N 4.8075°E |

| Architectural style(s) | Gothic |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Avignon: Papal Palace, Episcopal Ensemble and Avignon Bridge |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 1995 (19th session) |

| Reference no. | 228 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

The Palais des Papes (English: Palace of the Popes; lo Palais dei Papas in Occitan) in Avignon, Southern France, is one of the largest and most important medieval Gothic buildings in Europe.[1] Once a fortress and palace, the papal residence was a seat of Western Christianity during the 14th century. Six papal conclaves were held in the Palais, leading to the elections of Benedict XII in 1334, Clement VI in 1342, Innocent VI in 1352, Urban V in 1362, Gregory XI in 1370 and Benedict XIII in 1394. In 1995, the Palais des Papes was classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its outstanding architecture and historical importance for the papacy.[2]

Description

[edit]The Palais is actually two joined buildings: the old palais of Benedict XII, which sits on the impregnable rock of Doms, and the new palais of Clement VI, the most extravagant of the Avignon popes. Together they form the largest Gothic building of the Middle Ages. It is also one of the best examples of the International Gothic architectural style. The construction design was the work of two of France's best architects, Pierre Peysson and Jean de Louvres, and the lavish ornamentation was the work of two of the best students of the School of Siena (Italy), Simone Martini and Matteo Giovanetti.

In addition, the papal library housed in the Palais (the largest in Europe at the time with over 2,000 volumes), attracted a group of clerics passionate in the study of "belles-lettres", amongst them the founder of humanism, Petrarch. At the same time, composers, singers and musicians were drawn to the Great Chapel of the Palais. It was there that Clement VI used the Mass of Notre-Dame of Guillaume de Machaut, there that Philippe de Vitry at the pope's invitation presented his Ars Nova, and there that Johannes Ciconia came to study.

Due to its immense size, the Palais was also the place where the general organisation of the Church began to change. It facilitated the centralisation of services and the adaptation of operations in order to suit the needs of the papacy, creating a truly central administration for the Church.[3] The manpower of the Curia (Church administration), while 200 at the end of the 13th century, surpassed 300 at the beginning of the 14th century and reached 500 people in 1316. To this were added over 1,000 lay officials working within the Palais.[4]

Despite this, the Palais became obsolete when the papacy found it necessary to return to Rome. The hope of reuniting Latin and Orthodox Christians, along with the achievement of peace in the Papal States in Italy, made the case for returning stronger. Added to that was the strong conviction of both Urban V and Gregory XI that the seat of the papacy could only be the tomb of St Peter. Despite strong opposition from the Court of France and the College of Cardinals, both popes found the means to return to Rome, the first, on 30 April 1362, the second on 13 September 1370. This time, the return was absolute.[4]

In the following centuries, the Palais lost all of its former glory, despite serving as the seat of two anti-popes and many cardinals. It retained, however, a "work of destruction" aspect that French poets and writers such as Charles Forbes René de Montalembert have referred to over the centuries, with its powerful sense of beauty, simplicity, grandeur and immortality.[5]

History

[edit]

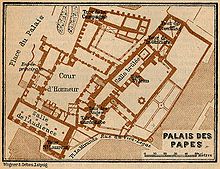

The palace's groundbreaking began in AD 1252. Under Philip IV of France who had conflict with Pope Boniface VIII which ended in his death and Pope Benedict XI a mere puppet of Philip who only lasted eight months, Avignon would become the residence of succeeding pontiffs in 1309, when the Gascon Bertrand de Goth, as Pope Clement V, unwilling to face the violent chaos of Rome after his election (1305), moved the Papal Curia to Avignon during the "Avignon Papacy". Clement lived as a guest in the Dominican monastery at Avignon, and his successor Pope John XXII set up a magnificent establishment there, but the reconstruction of the old bishops' palace was begun in earnest by Pope Benedict XII (1334–42) and continued by his successors to 1364. The site, on a natural rocky outcrop at the northern edge of Avignon, overlooking the river Rhône, was that of the old episcopal palace of the bishops of Avignon. The Palais was built in two principal phases with two distinct segments, known as the Palais Vieux (Old Palace) and Palais Neuf (New Palace). By the time of its completion, it occupied an area of 11,000 m2 (118,403 sq ft). The building was enormously expensive, consuming much of the papacy's income during its construction.

The Palais Vieux was constructed by the architect Pierre Poisson of Mirepoix at the instruction of Pope Benedict XII. The austere Benedict had the original episcopal palace razed and replaced with a much larger building centred on a cloister, heavily fortified against attackers. Its four wings are flanked with high towers.

Under Popes Clement VI, Innocent VI and Urban V, the building was expanded to form what is now known as the Palais Neuf. An architect, Jean de Louvres, was commissioned by Clement VI to build a new tower and adjoining buildings, including a 52-metre (171 ft) long Grand Chapel to serve as the location for papal acts of worship. Two more towers and a bridge were built under Innocent VI. Urban V completed the main courtyard (known as the Court of Honor) with further buildings enclosing it. The interior of the building was sumptuously decorated with frescos, tapestries, paintings, sculptures, and wooden ceilings.

The popes departed Avignon in 1377, returning to Rome, but this prompted the Papal Schism during which time the antipopes Clement VII and Benedict XIII made Avignon their home until 1403. The latter was imprisoned in the Palais for five years after being besieged in 1398 when the army of Geoffrey Boucicaut occupied Avignon. The building remained in the hands of antipapal forces for some years – it was besieged from 1410 to 1411 – but was returned to the authority of papal legates in 1433.

Although the Palais remained under papal control (along with the surrounding city and Comtat Venaissin) for over 350 years afterward, it gradually deteriorated despite a restoration in 1516. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789 it was already in a bad state when it was seized and sacked by revolutionary forces. In 1791 it became the scene of a massacre of counter-revolutionaries, whose bodies were thrown into the Tour des Latrines in the Palais Vieux.

The Palais was subsequently taken over by the Napoleonic French state for use as a military barracks and prison. Although it was further damaged by the military occupation, especially under the anti-clerical Third Republic when the remaining interior woodwork was cleared away for use of the structure as a stables – the frescos were covered over and largely destroyed – this ensured the shell of the building's physical survival. It was vacated in only 1906, when it became a national museum. It has been under virtually constant restoration ever since.

Charles Dickens describes a tour around this building in his book, Pictures from Italy. He describes his guide as a she-devil with flashing black eyes who glories in the gory past when the building was used as a torture chamber.[6]

Present

[edit]

The Palais today is a historical and architectural landmark and primarily a tourist attraction, drawing around 650,000 visitors per annum, putting it regularly in the top ten most visited attractions in France.[7] It also houses a large convention centre and the archives of the département of Vaucluse, which include a research centre on the papacy of Avignon, organised jointly by the École française de Rome and the institut de recherche et d'histoire des textes.

The Palais regularly serves as an exhibition centre. The first major exhibition was initiated by René Char, in the Grand Chapel between 27 and 30 June 1947. Entitled "Exposition de peintures et sculptures contemporaines" (Exposition of contemporary painters and sculptors), it was the starting point for what would later become the Festival d'Avignon.[8]

The courtyard of the Palais des Papes is a central performance location during the Festival d'Avignon, which is held every year in July. It is also the site of many cultural and economic events including exhibitions, shows, and conventions.

The Palais is also home to the International Congress Centre,[9] which was established in 1976 and today hosts a large number of events annually. These include congresses, parliaments, symposia, reunions and other gatherings, with the largest room, the 'Grande Audience', able to hold up to 700 guests.

Architecture

[edit]With 15,000 square metres (160,000 sq ft) of floor space, the Palais is the largest Gothic palace in all of Europe[10] and, due to its many architectural merits, one of the most important in the world. These merits were highlighted by Viollet-le-Duc, author of "Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle" (Dictionary of French architecture from the 11th to the 16th century), who referred extensively to the Palais, including the thickness and height of its towers, the strength of its crenelated walls, the use of arches for support on its façades and its ability to withstand heavy and drawn-out sieges.

The towers

[edit]

1 – "tour de Trouillas" (tower of Trouillas, a village in the Pyrenees frequented by the Knights Templar)

2 – "tour des Latrines" (lavatory tower) or "de la Glacière" (icehouse tower)

3 – "tour des Cuisines" (kitchen tower)

4 – "tour Saint-Jean" (Saint John tower)

5 – "tour de l'Étude" (study tower)

6 – "tour des Anges" (angels' tower) or "tour du pape" (Pope's tower)

7 – "tour du Jardin" (garden tower)

8 – "tour de la Garde-Robe" (wardrobe tower)

9 – "tour Saint-Laurent" (Saint Lawrence tower)

10 – "tour de la Gache" (waste tower) (behind the palace)

11 – "tour d'angle" (angle tower) or "tour des Grands Dignitaires" (great dignitaries' tower) (underneath the roofline)

12 – "tour de la Campane" (bell tower)

Clément VI studium

[edit]

The studium, or private study of Clement VI, is commonly called the chambre du cerf (room of the stag), on account of the celebrated 14th-century frescoes, depicting courtly hunting scenes, that decorate the walls and vaults. The subject matter, while common in contemporary secular art, is as unexpected in a room supposedly dedicated to study as it is for a room in a papal apartment. The frescoes were probably painted by French artists, who were either highly influenced by Sienese art or assisted by Simone Martini and/or Matteo Giovanetti, both of whom served as Clement's court painter.

The Great Tinel

[edit]This room was used primarily as a reception room. Covered with tapestries on starry blue background, there is actually nothing left of these decorations. Indeed, a fire destroyed the palace in the 14th century: many parts have been restored or rebuilt.

During conclaves, it was in this room that the cardinals met to elect a new pope. For the occasion, the room was walled and only a small aperture was left open to provide all the necessary food. After each conclave, the temporary walls were destroyed, revealing a vaulted room opening to the rest of the palace.

The chapels

[edit]Saint-Martial chapel

[edit]

Located on the second level of the Saint-Jean tower, the Saint-Martial chapel relates through painting the main parts of Saint Martial's life. Matteo Giovanetti worked there in 1344 and 1345. The reading direction of the painting should be made from top to bottom.[11]

-

4 angels

-

Saint Martial Chapel – west wall and door

Saint-Jean chapel

[edit]

From 1347 to 1348, Matteo Giovannetti was in charge of the Saint-Jean chapel, located under the Saint-Martial chapel.[12] In contrast to the local holy figure Martial this chapel is dedicated to John the Baptist as well as John the Evangelist and is sometimes even implied to be a link back to Rome and Rome´s St. John Lateran. In this chapel painted by Matteo Giovannetti complex architecture in "perspective construction and developed fictitious rooms and places that are more illusionistic than any pictures before them" according to Dieter Blume an art historian and professor at the university of jena.[13]

Since the chapel is quite limited in space just like the one of Staint Martial, the painter used all available space to make the stories of the two saints known. This is why on the ceiling you can see both holy men and their parents, grandmothers who are half-sisters according to the bible and therefore ad strong familiar bonds between the two saints. The north and east walls are filled with the stories of John the Baptist while John the Evangelist resides over the south and west walls of the 5,6 m x 5,3 m and 10 m high chapel.[13][14]

Art exhibitions at the Palais des Papes

[edit]The Palais des Papes regularly hosts art exhibitions. The tradition began in 1947, when the art critic Christian Zervos and the poet René Char organised an exhibition of the likes of Matisse, Picasso, Braque and Mondrian.[15] The exhibitions shown since then include two exhibitions of Picasso (in 1970 and 1973), the comprehensive 2000 exhibition "La beauté in fabula"[16] and, more recently, the exhibition "Les Papesses" (2013) and single exhibitions of Miquel Barceló (2010) and Stefan Szczesny (2014).

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Historic Centre of Avignon: Papal Palace, Episcopal Ensemble and Avignon Bridge". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Centre historique d'Avignon: Palais des papes, ensemble épiscopal et Pont d'Avignon" [Historic Centre of Avignon: Palais des papes together with the Pont d'Avignon] (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 6 May 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Yves Renouard, La Papauté à Avignon, p. 7.

- ^ a b Raymond Dugrand et Robert Ferras, article Avignon, in La Grande Encyclopédie, T. III, p. 1354–1355, Éd. Larousse, Paris, 1972, ISBN 2-03-000903-2 (pour le T. III).

- ^ Du vandalisme en France – Lettre à M. Victor Hugo, Charles de Montalembert, Revue des Deux Mondes, tome 1, janv. – mars 1833

- ^ Charles Dickens: Pictures From Italy, 1846

- ^ "Palais des Papes – Avignon". Palais-des-papes.com. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Le Centre International des Congrès du Palais des Papes". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "The Pope's Palace | welcome". Palais-des-papes.com. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ "Saint-Martial chapel". Culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ "Saint-Jean chapel". Culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ a b Blume, Dieter (2015). Prof. Dr [Rom im Exil. Die fiktiven Räume des Matteo Giovanetti in Avignon translated to Rome in Exile. The fictional rooms of Matteo Giovanetti in Avignon] (in German). pp. S. 36–49.

- ^ Jacobs, Hanna Christine (2019). MA [Transformationen des Erzählraums. Matteo Giovannettis Fresken in der Johanneskapelle des Papstpalastes in Avignon translated to Transformation in the space of storytelling. Matteo Giovannettis Frescos in St. Johns chapel] (in German). Regensburg: Lukas Verlag. pp. S. 123–131.

- ^ See "Szczesny. Métamorphoses méditerranéennes", p. 7 (preface by Cécile Helle)

- ^ Millet, Bernard (30 November 2001). "La beauté in fabula". La pensée de midi (2): 112–113. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in English)

- The Popes Palace, visit and report

- (in Polish) Photos of the Popes Palace in Avignon

- World Heritage Sites in France

- Museums in Avignon

- Buildings and structures in Avignon

- Former palaces

- Avignon Papacy

- Gothic architecture in France

- Gothic palaces

- Tourist attractions in Avignon

- Museums in Vaucluse

- Historic house museums in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur

- Art museums and galleries in France

- Episcopal palaces

- 1309 establishments in Europe

- 14th-century establishments in the Papal States

- Palaces in France