Fort Ala Nova

Kastell Schwechat | |

| Alternative name | Schwechat Fort |

|---|---|

| Location | Schwechat |

| Region | Pannonia Superior |

| Coordinates | 48°8′38.1″N 16°28′11.7″E / 48.143917°N 16.469917°E |

| Altitude | 170 m (558 ft) |

| Type | Cavalry (alae) fort |

| Part of | Pannonian Limes |

| Length | 206 m |

| Width | 170 m |

| Area | 3.5 ha |

| History | |

| Material | a) Wood/soil fort b) Stone fort |

| Periods | a) Domitian 100–200 CE b) Severus 200 CE onward |

| Associated with | a) Ala I Thracum Victrix (?) b) Equites Dalmatae |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Not visible above ground |

| |

Fort Ala Nova, or also Schwechat Fort, is a former Roman cavalry fort (alae fort for 500 horsemen) situated within the Austrian section of the Upper Pannonian Limes. The fort was situated in the municipality of Schwechat, Lower Austria, a few kilometres east of Vienna. The area of the former cavalry fort encompassed the site of today's Alanovaplatz, the cemetery and the brewery grounds in the Klein-Schwechat district. The deployment of a mobile cavalry unit was a strategic necessity to more effectively secure the expansive plain between Vindobona and Carnuntum along the Danube and to facilitate rapid response in case of an emergency.

It is likely that Ala Nova was built in the late 2nd century, with the current Alanova Square initially comprising fortifications constructed from wood and earth. At the beginning of the 3rd century, the fort was rebuilt in the form of a rectangular, fortified structure enclosed by stone walls. It is evident that the fort underwent several phases of remodelling during its occupation, extending up to the 5th century. Based on the evidence of individual finds, it can be postulated that at least one civilian settlement (vicus) existed in the area surrounding the fort. Burial grounds have been discovered in the vicinity of Schwechat's main square and to the south of the fort, at Frauenfeld. Since 2021, the archaeological monument has been part of the Danubian Limes UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Location

[edit]

Schwechat is located on the north-eastern edge of the Vienna Basin at the outlet of the Schwechat river into the Danube and was named after this river. In the north-west, the city has grown together with Vienna in recent decades and borders directly on the 11th district of Vienna (Simmering).

The town is situated in a favourable location in terms of transport at the intersection of two important routes. In Schwechat, the route along the Danube is intersected by a route coming from the Leitha near Deutsch Brodersdorf, via Moosbrunn and Himberg and further along the Danube and its neighbouring floodplains to the north to Groß-Enzersdorf. There is evidence of settlement in the region since the Neolithic period. Over a period of around 6000 years, a conurbation with 16 large settlement areas developed over a length of just five kilometres. This is evidenced by archaeological sites on both sides of the Schwechat bottomlands.[1]

Schwechat is crossed by a total of five streams:

- the Liesing, which merges into the Schwechat river here,

- the Schwechat river, following the natural riverbed,

- the Schwechat-Mühlbach near Rothmühle Castle, which was drained and filled in the 1950s,

- the Mitterbach or Wildbach or "Wildes Wasser", an artificial relief channel of the Schwechat, which begins at Achau and takes in the majority of the water, and

- the Kalter Gang.

This divides the urban area into two parts, Klein-Schwechat in the west and Groß-Schwechat on the right bank of the Kalten Gang.[2] It can be assumed that bridges were built at this location since early times, which were most likely converted into stone bridges with the arrival of the Romans and the expansion of the Limes road. However, no evidence of this has yet been found.[3]

The former auxiliary fort was located in Klein-Schwechat on the site of today's Alanovaplatz, the cemetery and the brewery grounds just a few hundred metres south of the ancient steep bank of the Danube (today called am Grund). The stationing of a mobile cavalry unit was necessary in order to better secure the wide and flat plain between Vindobona and Carnuntum and to be able to intervene quickly in an emergency. The river crossings and the bridges over the three rivers in Schwechat also had a certain strategic importance, which can be deduced from the accumulation of archaeological traces (pointed ditches) of two to possibly three wood-earth camps in the immediate vicinity of these rivers. In the fort chain of the Limes, Ala Nova was located about six Roman miles (nine kilometres) south-east of the legionary camp of Vindobona and 21 Roman miles (31.1 km) west of the metropolis of (Upper) Pannonia, Carnuntum (Petronell).[3]

Name

[edit]

Ala Nova means newly established cavalry division (Latin ala = cavalry division, nova = new).

Ala Nova is mentioned twice in ancient literature. The Itinerarium Antonini, a newly edited road directory from around 300 CE, mentions Ala Nova near Aequinoctio (Fischamend), a post that was located almost exactly halfway between Vindobona and Carnuntum ("Aequinoctio et Ala Nova in medio Vindobona"). The Itinerarium gives the distance between Carnuntum and Vindobona as 27 Roman miles, which corresponds to around 40.5 kilometres.[4]

The Notitia Dignitatum, an administrative handbook from the 5th century, also mentions an Alanoua[5] or an Ala nova, together with the last unit to be stationed there, the equites Dalmatae Ala nova.[6]

In 98 CE, the Ala I Flavia Britannica in Vindobona/Vienna was replaced by the Legio XIII Gemina. It may have been an endeavour to additionally secure the new legionary base at Vindobona on its south-eastern flank. A fort was built in Schwechat for this purpose. The Roman place name Ala Nova can probably be traced back to a (possibly completely newly established) cavalry unit stationed in Schwechat. The name could also derive from the fact that the new cavalry camp was built north of an existing wood-earth camp on the west bank of the Schwechat river. According to Hannsjörg Ubl (1980), the question arises whether the ancient name Ala or Ala Nova could actually be traced back to this older camp.[7]

Research history

[edit]Early findings

[edit]The first indications of Schwechat's Roman past were provided in the "Antike Reise" by F. F. Wächter from 1821, in which he mentions "... old walls in the cemetery of Schwechat".[8] Records of the Schwechat notary Franz Schranzhofer show that remains of Roman walls were still visible in the seventies of the 19th century.[9] In 1843 and 1844, six Roman milestones were found in a well on the western edge of the town, which originally stood 21 Roman miles from Carnuntum.[10] In 1879, during fieldwork near the Schwechat cemetery on Frauenfeld, a 60 cm high bulbous clay pot was discovered containing a coin hoard with around 12,000 silver-plated copper coins from the 4th century (306 to 361 CE).[11]

Excavations 1910-1937

[edit]As part of the lively building activity at the turn of the 20th century, many coins, masonry and numerous bricks with Legio X Gemina stamps were once again found. In most cases, however, the finds ended up in the hands of private collectors without any scientific documentation.[12]

In spring 1910, Johann Ableidinger, former mayor and local historian of Schwechat, discovered the profile of the fort moat and the foundations of the enclosing wall during excavation work for a beer canal on the Dreher Brewery site.[13] The subsequent investigations carried out by Josef Nowalski de Lilia led to the reconstruction of the course of the rampart and the remains of a barracks could be determined. In autumn 1910, the archaeologist of the Limes Commission, Eduard Nowotny, succeeded in uncovering and subsequently documenting a considerable part of the western fortifications on the brewery site.[14] However, these excavation results did not yet allow the extent of the camp to be determined. In 1937, Roman masonry was again discovered during excavation work in the vicinity of the cemetery. During the construction of a drainage channel at Alanovaplatz, the south-eastern front of the fort was then cut into, which meant that the dimensions of the camp were known around 40 years after its discovery.[15]

Excavations 1979-2009

[edit]In the years following the Second World War, several smaller excavations took place, particularly around Saint Jacob's Church on Schwechat's main square and during reconstruction work on the numerous war-damaged buildings in the area of this square and on the grounds of the district administration.[16][17] It was not until 1979 that another important archaeological find was made. During the construction of a new residential complex on Frauenfeld, Hannsjörg Ubl from the Federal Monuments Office was able to identify cut pointed ditches at the north-east corner of the excavation pit.[18] The discovery of fortification and beam trenches was an indication of a possible wood-earth complex at this location, around 400 metres south of the previously known fort Ala Nova. Ubl suspects that this wood-earth complex is older than the fort. This was confirmed by Ursula Langenecker from the Federal Monuments Office in 1994 with the discovery of further pointed ditches in the immediate vicinity of the first site.[19] Unfortunately, the area where the early wood-earth camp is thought to have been located has been largely destroyed by intensive residential development.

A small-scale archaeological investigation in the area of the Alanovaplatz under the direction of Krista Süss from the AUSINA association in 2000 provided evidence of two stone construction phases of the fort and a presumed early wooden construction phase of the camp.[20]

Investigations since 2010

[edit]Since the excavation in 1910, there has been no systematic investigation of the Roman fort in Schwechat. The history of the camp and the associated questions therefore remained largely unanswered for a long time. A new turning point in the history of research into Roman Schwechat came in 2010, when two large-scale excavations were carried out on the site of the former fort between Alanovaplatz and Wiener Straße and in the Frauenfeld district, at the junction of Gladbeckstraße and Klederinger Straße. Both excavations were commissioned by the Federal Monuments Office and were carried out by the company AS-Archäologie Service.[21]

At Frauenfeld, under the direction of Mag. Igl and Mag. Leingartner, an extensive civilian Roman cemetery was discovered and investigated alongside several Lombard graves, most of which had been looted. Numerous cremation graves, some with rich grave goods, and a number of inhumations were uncovered. Preliminary analyses allow the finds to be dated to the 2nd to 4th century CE. The location of the graves suggested the course of a burial route, which, however, could no longer be verified due to the relatively shallow location of the finds.[22]

The excavation work at Alanovaplatz under the direction of Mr Scholz provided fundamental new findings. Two barracks buildings were almost completely recorded, and several repair phases were identified. However, a first Roman timber construction phase could not be confirmed. However, there are clear indications of an earlier settlement on the site. Of particular interest were finds from a late remodelling phase from the 4th/5th century, with which the conversion of a military camp into a civilian settlement area in stone construction could be clearly documented. Of almost sensational value is the first Austrian evidence of an Avar-era settlement within a Roman camp. These excavations, which were completed at the beginning of November 2010, provided numerous new findings that would shed new light on the size, location and history of Ala Nova.[23]

These two stratigraphic excavations and their numerous finds have been comprehensively analysed since 2012 as part of a research project by the Austrian Archaeological Institute, led by Stefan Groh.[24][25]

In November 2011, a geophysical prospection was carried out by the Central Institution for Meteorology and Geodynamics on behalf of the municipality of Schwechat and Asset One Immobilienentwicklung AG on the former site of the Schwechat brewery west of the Klein-Schwechat cemetery, where further remains of the Roman cavalry fort are suspected. In particular, the georadar measurements show a rectangular structure (9 × 35 m) with an apparently preserved stone floor and internal subdivisions at a depth of around 0.75 metres. Other parallel structures and a ditch are also recognisable.[26]

Wood-earth camp and stone fort

[edit]Early wood-earth camp

[edit]The existence of an early wood-earth camp in Schwechat has not yet been clearly established. The most recent excavations in 2010 at Alanovaplatz were unable to provide evidence of an extensive timber construction phase. In the south-east area of the excavation site, some indications of an early construction phase could be identified, but no structures or buildings could be deduced from the findings. The finds from this possible early storage phase can be dated to the second half of the 2nd century. Another indication of an early wood-earth camp, albeit south of the stone fort at the junction of Gladbeckstraße and Brauhausstraße, in the immediate vicinity of the Mühlbach stream that ran at this point at the time, where H. Ubl[18] in 1979 and U. Langenecker in 1994[19] were able to identify moats. In the immediate vicinity to the east, barrows could also be seen in the topsoil. Hannsjörg Ubl believes to have discovered an early wood-earth camp at this site and assumes a dating to the Flavian period (Hannsjörg Ubl, 1980). Among other things, Roman pottery and fragments of relief-decorated terra sigillata bowls were recovered from this area in 1976.[27] In the 1994 investigation report, the excavated trench is described as a precisely excavated, pointed ditch. Its depth was 1.8 m (2.6 m below the top of the humus), the maximum width 3.8 m. However, the finds from the lowest layers were no longer suitable for exact dating due to their poor state of preservation or heavy wear. The finds from the upper backfill of the ditch cannot be dated before the second half of the 2nd century.[19] In order to determine the extent, orientation and dating of the camp, further excavations would be necessary in the few areas of this site that have not yet been destroyed.

As part of an excavation campaign in June 1950 in connection with the reconstruction of the war-damaged St James' Church in Groß Schwechat, the profiles of two pointed ditches were again cut at Hauptplatz 21a, the Roman origin of which was proven. However, a more precise dating was not possible.[16] Strangely enough, this evidence was not recognised in later literature and scientific discussions. Whether these pointed ditches indicate an early marching camp or wood-earth camp on the eastern bank of the river in Schwechat, or served as an enclosure or demarcation of a grave of the Roman cemetery located at this site, cannot be answered at present.

Ala Nova Fort

[edit]

The investigations by E. Nowotny and J. Ableidinger between 1910 and 1937 made it possible to determine the exact size and position of the stone fort. The excavation in spring 1910 by the k&k Limes Commission under the direction of E. Nowotny led to the discovery of a considerable part of the camp fortification on the former site of the Dreher brewery.[14] In the area of Alanovaplatz and the cemetery, it was possible to confirm the existence of the camp front (left principle side) extending from north-east to south-west along a line of 153 metres, which was pierced in the northern section by a 19-metre-wide gateway. The south-western fort front joined the north-western front after a rounded corner at an angle of 88.5 degrees, the course of which could be observed up to a length of 160 metres.

Two finds by J. Ableidinger (a water pipe trench in June 1928 in the house at Wiener Straße 35 and canal work at Alanovaplatz in 1937) were thought to have determined the exact dimensions of the camp.[28] An ancient wall 30 to 40 metres behind the wall alignment of the houses at Wiener Strasse 33 and 35 was interpreted as the camp wall, and the side length of the camp was determined to be 206 metres. The most recent excavation in 2010 at Alanovaplatz was able to identify the northern pointed ditch directly along Wienerstraße, so that the camp wall, even if no artefacts are detectable, must lie around 20 m further north than previously assumed. The cutting of the south-eastern long side in 1937 revealed the width of the camp: the inner width was 168 metres and the wall was two metres thick. The Schwechat camp covered an area of approx. 225 × 170 metres, i.e. 3.8 hectares; this size was quite usual for an auxiliary force of 500 men. The south-west corner of the fort was rounded and additionally reinforced with a relatively small square tower with a side length of six metres that was only slightly offset inwards. In the centre of the line between the south-western corner of the camp and the porta principalis sinistra there was an intermediate tower attached to the inside. This had the same dimensions as the south-west corner tower, only the wall was slightly thinner.[14]

Two construction phases were identified in the western weir ditch:[14]

- Ditch I: The enclosure wall was adjoined by a 1.65 to 1.80 metre wide berm, followed by a ditch about six metres wide, with a trapezoidal cross-section water drainage groove (cunette) in the centre of the ditch.

- Ditch II: The earlier ditch was overlaid by a second, larger one, which had a width of 9.55 metres according to Nowotny, 11.40 metres according to Ableidinger and was about four metres below the present ground level. A berm about two metres wide was found between the wall and the ditch. The moat widened near the gate and was slightly bulged at this point.

The foundation pit of the rampart wall was about five Roman feet (1.46 to 1.65 metres). The foundation walls appeared to be made of white concrete mortar. The rising masonry was probably made of Sarmatian shell-bearing sandstone from Atzgersdorf. Parts of a wall were found in the trench, which had obviously collapsed during the destruction of the fort. Judging by the amount of rubble, the wall must have been at least five to six metres high.[29] Inside the enclosing wall were the battlements, which were three metres wide and could be recognised by the postholes that supported the battlements on the inside.[14]

The discovery of the west gate, the porta principalis sinistra, was particularly remarkable. As with the fort wall, its dimensions could only be reconstructed from the foundation pits. It was a vaulted double gate with a width of 19 metres, flanked by two rectangular towers. There was a walkway between the towers.[14] During the excavation of the gate, a hollow brick was found in a niche in the wall, which was probably part of the heating system for the upper guardrooms. By locating the west gate, the relatively coarse paving of the via principalis and two wall remains around 60 cm high were uncovered. The width of the via principalis was 17.23 metres (60 Roman feet).

On the western perimeter wall, the intervallum (gap) could be traced to 9.95 metres through a 60-centimetre-wide wall pit and an inwardly adjoining screed. On the decuman front (the rear part, the half of the camp not facing the enemy), the paving of the camp road could be traced to a length of 16.65 metres. A small section of the concreted embankment could be seen at the western intermediate tower.[14]

The administrative centre of every larger fort was the staff building, the principia with the camp or flag sanctuary. Today, a cemetery chapel stands on the site of the principia of Ala Nova. It is the last remnant of the parish church of Maria am Anger, which had to be demolished in 1815 due to dilapidation. It is striking that the foundations of the chapel and the former church run parallel to the enclosing walls of the fort and are therefore most likely connected to them.[29] J. Ableidinger assumed that the interior buildings of the camp were mainly made of wood, whereas the staff building (principia) and the flag sanctuary were built of stone. This is also suggested by the discovery of two columns within the cemetery, on the former fort site, in the 19th century[29]

In 2000, an excavation was carried out by the AUSINA association (led by Krista Süss).[20] The excavation revealed that the Middle Imperial period building finds manifested themselves in two stone periods. Worth mentioning is the discovery under the oldest wall courses of a strongly profiled fibula with a perforated pin holder, which can probably be dated to the 1st century. The three different find horizons reflect the intensive use of the camp area and are attributed to stone construction periods I and II.[20] However, it remains unclear whether the remains of the walls found were part of a barracks or a stable. The discovery of post settings under the Ala Nova stone fort deserves attention. What is surprising is the orientation of this post line, which was clearly distinguished from the stone construction by its exact north-south alignment and also by its elevation.[20]

The 2010 excavation provided completely new findings. The initial findings from the 2000 excavation regarding the existence of an early wood-earth camp could not be confirmed. Instead, it has now been recognised that the Roman fort was built on an already inhabited area. The current findings show that the cavalry camp is larger than previously assumed. Barracks were found where the eastern fort wall and ditch were expected. The ditch could be identified in the north, albeit much further north than expected. The discovery of a civilian settlement on the area camp in the late 4th or early 5th century shows that a similar development took place in Ala Nova as in the neighbouring camps or forts.[23]

Occupation

[edit]The occupation of the early wood-earth camp is not known. The name of the cavalry unit that was stationed there after the expansion of Stone Fort I is also unknown. For the 2nd century, the Ala I Thracum Victrix was initially under discussion, but new finds of brick stamps prove with great certainty the location of this troop near Petronell-Carnuntum. It has also already been postulated that Ala Nova had no troops of its own and that the camp was possibly only an ‘outpost’ of one of the neighbouring legionary fortresses, Vindobona or Carnuntum.[30] For late antiquity, however, a cavalry unit of the Equites Dalmatae for Ala Nova (also for the neighbouring fort of Aequinoctium/Fischamend) can still be clearly assigned - in connection with the records from the Notitia dignitatum.[6]

Vicus

[edit]The exact location of the civilian settlement of Ala Nova has remained unknown to date. Settlement features have only been documented in a few places in Schwechat. A pit with finds from the 2nd to 3rd centuries was found south of the fort area. The backfill of the fort ditch contained artefacts that could be related to a settlement.[19] Over the last 200 years, numerous stray artefacts, mainly pottery, have been found within the brewery site. It is highly probable that the vicus, which was probably built at the same time as the fort, was located to the south of the camp, but its exact extent has not yet been determined due to heavy overbuilding. However, it is questionable whether this can ever be clarified beyond doubt, as the vicus was probably largely located on the site of the brewery, where large-scale earthworks were carried out at the end of the 19th century for the construction of large beer cellars. This also explains the many barely documented finds from this period. Roman finds on the right bank of the Schwechat, where an ancient oven was discovered in Sendnergasse, for example, are further traces of Roman settlement.[31]

Burial grounds

[edit]

The records of J. Ableidinger show that a cadaver field was found on the brewery site as early as the 19th century, and numerous other finds were also unearthed.[29] However, they were stolen by collectors and therefore not scientifically recorded. Further graves were discovered to the south of the fort area. In 1929, for example, an early imperial cremation grave was identified among the burials from the Migration Period in the Ried Frauenfeld burial grounds.[32] To the right of Brauereistraße, in the direction of the cadastral district of Rannersdorf, probably still in the Frauenfeld area, three further body graves from the Roman period were unearthed in 1968.[33]

Another burial site is located in the area of Schwechat's main square, as a number of late antique burials were secured there. One of the oldest documented finds is a Roman skeleton grave, which was discovered in 1923 at Hauptplatz 5.[34] A further four Roman graves were described by M. Müllner in 1927 (also on the main square).[35] In the same year, a Roman grave with various vessels was found in the courtyard of the former district court (now the district administration).[32] On 31 March 1933, J. Ableidinger uncovered a Roman stone slab grave in the south-eastern corner of the Hammerbrothütte. It was probably an equestrian grave from the early 4th century, at least according to the grave goods found next to the skeleton of a 35-year-old man, a horseshoe, an iron buckle, a knife and some horse teeth. A gravestone from the 2nd half of the 3rd century had been used as a cover for this grave.[36] The equestrian grave was restored and conserved and placed in the entrance hall of the Bundesgymnasium/Bundesrealgymnasium. In 1950, E. Neumann reported the discovery of several graves and golden earrings during a basic excavation in the course of repairing war damage at Hauptplatz 21 and 21a. In this context, a late Roman sarcophagus was also recovered at Hauptplatz 23.[37]

During the removal of war damage at Hauptplatz 6, three sarcophagi with body burials and a vessel were found, as well as two earth burials (without grave goods). At the corner plot of Hauptplatz, Bruck-Hainburgerstraße, formerly Neckam (Hauptplatz 3), a twisted gold earring was found despite the destruction of the child's grave there.[38] In 1958, Hans Walter uncovered a skeleton with its head facing east during earthworks for a new road within the grounds of the Schwechat brewery between Flaschenhalle and the former Soma plant. The upper body was raised at an angle of 70 degrees. A bronze coin (reduced follis of Constantius Chlorus, 293-306, minted in Ticinum) was found on the left hand. The skeleton was handed over to the Landesmuseum Niederösterreich (since 2015: Museum Niederösterreich), the coin is owned by the Schwechat brewery.[39] In 1963, skeletal remains and Roman pottery shards were discovered in the excavation of a 2.50 metre deep trench in Sendnergasse/corner of Hauptplatz, where some body graves had apparently been destroyed.[40] During the excavation of the foundations for the district administration building at Hauptplatz 3 in 1964, a body burial that was aligned parallel to the pavement was destroyed.[40] The extent of the burial grounds on Hauptplatz is unknown, all that is known is that it is located in the area of the Limes Road, which once ran through this area.

The 2010 excavations at Frauenfeld revealed extensive civilian burial grounds to the south of the camp area. The graves were largely unplundered. Some of the cremation graves and inhumations were very richly furnished with grave goods.[41] The position and concentration of the burials suggest an east-west burial route. Due to the relatively shallow depth of the finds - no walking horizon could be determined - this burial route could no longer be proven.

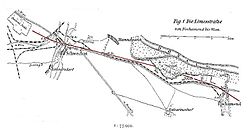

Limes road and milestones near Ala Nova

[edit]

Part of the Limes road of the Carnuntum-Schwechat section is located near the Mannswörth railway stop. Its further course eastwards could be traced for around 1.5 kilometres along a break in the banks of the Danube into the Poigenau and in some gravel pits. To the west of the Mannswörth stop, the former Limes road runs about 1.5 kilometres under the present railway embankment and emerges again where the present parallel road turns away from the railway. The Limes road from Schwechat to Vienna probably did not run directly through the camp area,[14] but probably southwest of today's cemetery towards the Klein-Schwechat railway station, where it made a bend and continued to the eastern wall of the central cemetery, under whose administrative buildings it appears to continue along Simmeringer Hauptstraße in the direction of the former Vindobona legionary camp.[42][43]

The location of the assumed road junction to the Ala Nova camp remains unknown. It can be assumed that the junction of the Limes road leading to Ala Nova was only constructed after the crossings over the Schwechat rivers, probably to the south-west of the fort; this is because the vicus is also assumed to be there and no evidence has yet been found that the former Limes road was located at the site of today's Wienerstraße.[14]

An accumulation of milestones such as the six,[44] which presumably originally stood on the eastern bank of the Schwechat and indicated the distance from Carnuntum, leads to the conclusion that this point was also the boundary to the city and camp territory of Carnuntum. For this reason, the Schwechat was assumed to be the border between the territories of Carnuntum and Vindobona. However, the reason for the erection of six milestones within a few years around the middle of the 3rd century near Schwechat, and thus on a main east-west traffic route, may not only have been road and bridge repairs, but certainly also political propaganda, as the emperors currently reigning were usually immortalised on such milestones with their full titles to emphasise their achievements for the respective province duly.[45]

Monument protection and location of finds

[edit]All the sites described here are archaeological monuments within the meaning of the Austrian Monument Protection Law. Excavating and collecting artefacts and finds without the permission of the Federal Monuments Office is a punishable offence. Accidental finds of archaeological objects (walls, ceramics, coins, bones, etc.) and all measures interfering with the ground must be reported to the Federal Monuments Office.[46]

Many of J. Ableidinger's finds are kept in the Lower Austria Museum in St. Pölten (Ableidinger Collection).[47] The finds from the smaller excavation in 2000 are currently stored by the municipality of Schwechat. Some of the finds from both excavations in 2010 (fort and cemetery) were shown to the public following their restoration as part of an exhibition in 2011 ("Spuren der Zeit" exhibition in the Schwechat municipal library). Unfortunately, the finds are currently no longer accessible to the public and are mainly stored in the Kulturfabrik Hainburg.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ Sauer (2006, p. 61)

- ^ Adamec, Friedrich (1986). Schwechats Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (in German). Schwechat: Stadtgemeinde Schwechat.

- ^ a b Groller von Mildensee, Maximilian (1904). "Straßenforschung". Der römische Limes in Österreich (in German). Vol. 5. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ Itinerarium Antonini, vol. 2, p. 246.

- ^ Notitia dignitatum Occidentis, 34, 7.

- ^ a b Notitia dignitatum Occidentis, 34, 18.

- ^ Ubl (1980, p. 602)

- ^ Kubitschek (1906, p. 107): "… alte Mauern im Gottesacker von Schwechat" (original).

- ^ Ableidinger (1929, p. 30)

- ^ Weber, Ekkehard (1968–1971). "Die römischen Meilensteine aus dem österreichischen Pannonien". Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien (in German). 49: 121–145.

- ^ Ableidinger (1929, p. 32)

- ^ Ableidinger (1929, p. 31)

- ^ Ableidinger (1929, p. VI)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nowotny (1911, p. 44)

- ^ Genser (1986, p. 536)

- ^ a b Neumann (1950, p. 24)

- ^ Neumann (1950, p. 9)

- ^ a b See Ubl (1980).

- ^ a b c d Langenecker, Ursula (1994). "Ein mittelbronzezeitlicher Blechgürtel vom Typ Sieding-Szeged aus Margarethen am Moos, Niederösterreich". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 33: 269–272.

- ^ a b c d Krenn, Martin (2000). "Bericht zu den Ausgrabungen des Vereins ASINOE im Projektjahr 2000". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 39: 181–337.

- ^ "Willkommen". www.archaeologie-service.at (in German). Retrieved 2024-08-14.

- ^ Igl, Roman; Leingartner, Bernhard (2009). "Götter - Gräber - Kalkbrennöfen. Neue Befunde aus Lauriacum/Enns". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 48.

- ^ a b Scholz, Ute (2009). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 48: 317–319.

- ^ "Forschungen im Kastell und Gräberfeld Ala Nova-Schwechat am nordwestpannonischen Limes (Niederösterreich)". Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut (in German). Archived from the original on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ "Forschungen zum norisch-pannonischen Donaulimes - Schwechat-Ala Nova" (PDF). Wissenschaftlicher Jahresbericht des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts (in German): 63–65. 2013.

- ^ Seren, Sirri; Totschnig, Ralf (2011). "KG Schwechat, SG Schwechat". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 50: 294.

- ^ Nowak, Heinz (1976). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 15: 273.

- ^ Kandler, Manfred (1980). "Eine unpublizierte Beobachtung zum Kastell Schwechat – Ala Nova". Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft der Freunde Carnuntums (in German). 4: 3.

- ^ a b c d Ableidinger (1929)

- ^ Fitz, Jenö (1962). "A MILITARY HISTORY OF PANNÓNIA FROM THE MARCOMANN WARS TO THE DEATH OF ALEXANDER SEVERUS (180—235)" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 16.

- ^ Hetzer, Kurt (1930–34). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 1.

- ^ a b Wimmer, Friedrich (1930–34). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 1.

- ^ Engelhardt, Kristin (1966). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 9.

- ^ Ableidinger, Johann (1930–34). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 1: 59.

- ^ Müllner, M. (1930–34). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German) (1).

- ^ Ableidinger, Johann (1930–34). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 1: 238.

- ^ Neumann, Alfred (1946–50). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 5: 135.

- ^ Neumann, Alfred (1951–55). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 6: 100.

- ^ Walter, Hans (1956–60). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 7: 111.

- ^ a b Moßler, Gertrud (1961–65). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 8: 101.

- ^ Krenn, Martin (2009). "?". Fundberichte aus Österreich (in German). 48: 428.

- ^ Groller von Mildensee, Maximilian (1904). "Straßenforschung". Der römische Limes in Österreich (in German). Vol. 5. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. p. 3.

- ^ Groller von Mildensee, Maximilian (1904). "Straßenforschung". Der römische Limes in Österreich (in German). Vol. 4. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. p. 5.

- ^ CIL III, 04641; CIL III, 04642; CIL III, 04643; CIL III, 04644; CIL III, 04645; CIL III, 04646.

- ^ Weber, Ekkehard (1968–1971). "Die römischen Meilensteine aus dem österreichischen Pannonien". Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien (in German). 49: 126.

- ^ "FRE Österreich - Schwechat / ALA NOVA". limes.univie.ac.at (in German). Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ Wastyn, Marnik M. (2022). Archäologische Funde aus Schwechat: Fundkatalog von der Urgeschichte bis in die Neuzeit (in German). Wien: Phoibos Verlag. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-3-85161-281-3.

- ^ "SPUREN DER ZEIT". Volkspartei | (in German). Retrieved 2024-08-20.

Literature

[edit]- Ableidinger, Johann (1929). Geschichte von Schwechat (in German). Schwechat: Stadtgemeinde Schwechat.

- Genser, Kurt (1986). Der österreichische Donaulimes zur Römerzeit. Ein Forschungsbericht. Der römische Limes in Österreich (in German). Vol. 33. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Kandler, Manfred, ed. (1989). Der römische Limes in Österreich: ein Führer (in German) (2. ed.). Wien: Verl. d. Österreich. Akad. d. Wiss. ISBN 978-3-7001-0785-9.

- Kubitschek, Wilhelm (1906). "Carnuntina". Österreich. Zentral-Kommission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und Historischen Denkmale: Jahrbuch der K. K. Zentral-Kommission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und Historischen Denkmale (in German). 4 (1): 105–144. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.47869.8.

- Neumann, Alfred (1950). Ausgrabungen und Funde im Wiener Stadtgebiet 1949/1950 (in German). Vienna: Veröff. d. Hist. Mus. d. Stadt Wien 3.

- Nowotny, Eduard (1911). "Die Grabung in Schwechat". Anzeiger der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Phil.-hist. Klasse (in German). 48.

- Sauer, Franz (2006). Fundstelle Rannersdorf. Die archäologischen Grabungen auf der Trasse der S1 (in German). Vienna: Bundesdenkmalamt.

- Ubl, Hannsjörg (1980). "Der österreichische Abschnitt des Donaulimes. Ein Forschungsbericht (1970–1979)". In Hanson, William; Keppie, Lawrence (eds.). Roman frontier studies 1979: papers presented to the 12th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. British Archaeological Reports. Oxford: BAR. ISBN 0-86054-080-4.