Church of the Jacobins

| Church of the Jacobins (Toulouse) | |

|---|---|

Church of the Jacobins | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Province | Archdiocese of Toulouse |

| Region | Midi-Pyrénées |

| Status | Museum |

| Location | |

| Location | Toulouse, France |

| State | Haute-Garonne |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°36′14″N 1°26′24″E / 43.6039°N 1.4400°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church |

| Style | Southern French Gothic |

| Website | |

| http://www.jacobins.toulouse.fr/anglais | |

The Church of the Jacobins is a deconsecrated Roman Catholic church located in Toulouse, France. It is a large brick building whose construction started in 1230, and whose architecture influenced the development of the Gothique méridional (Southern French Gothic) style.[1] The relics of Thomas Aquinas are housed there. In the two centuries following the dissolution in France of the Dominican Order at the time of the French Revolution, it served various different purposes before undergoing major restoration in the 20th century. In the early 21st century, it was partially converted into a museum.

Toulouse being the city where the Dominican order was founded in 1215, the Convent of the Jacobins of Toulouse is sometimes considered the mother church of the order, although it was not the first convent built by the Dominican friars.[2] Other churches such as Santa Sabina in Rome also claim this title.

Name

[edit]The name Jacobins is the nickname that was given to the Dominican Order in the Middle Ages in France. Their first convent in Paris was located in the rue Saint-Jacques, (Latin Jacobus), and that name came to be attached to the order itself.[3]

The building complex is called a convent, although nowadays this term usually refers to a community of women, because in its historical usage the term convent was applied to communities of mendicant orders to differentiate them from the monasteries of monastics.

History

[edit]First church

[edit]In Languedoc in the early 13th century, Catharism, which the Catholic Church considered a heresy, was strong and growing.[4] In 1215, the future Saint Dominic founded in Toulouse a small community of monastic preachers to combat the heresy, and starting in 1230, the friars began the construction of a small church in which to preach.[5] Built entirely of pink Roman brick, this first building was half as long and half as high as the present church, and very simple in design, in line with the order's vow of poverty. It consisted of a double nave, one side for the friars, and one for the congregation, separated by pillars and screens.[6]

Expansion

[edit]

Over the next century, as congregations grew, the church was enlarged and embellished. Between 1245 and 1252, it was extended with the addition of a choir with side chapels. Between 1275 and 1292, the height of the choir was increased, and a vaulted roof constructed. In response to the technical difficulty posed by creating a vaulted roof for the new space, the builders installed one oversized column in the centre from which the ribs radiated outwards in all directions. This feature has come to be known as Le Palmier des Jacobins, the palm tree of the Jacobins.[1]

Between 1275 and 1315, the height of the choir was increased, and high windows created above the chapels. The seven-storey bell tower was also added at this time. Starting in 1325, a new, higher vaulted roof was constructed for the nave in order to bring it into line with the choir. The last component of the century-long expansion of the church was the construction of the chapel of Saint Antonin (separate from the church itself), between 1335 and 1341.[6]

Relics

[edit]

Thomas Aquinas, author of the Summa Theologiae and canonised in 1323, was a member of the Dominican order. In 1368 Pope Urban V decreed that his remains be transferred from Italy where he died to the Jacobins, the mother church of the order. When they arrived in 1369, they were placed in a stone reliquary beside the altar. After being moved to Saint Sernin at the time of the Revolution, they were returned to the Jacobins in 1974 when the restoration of the church was complete.[7]

Dissolution

[edit]Following the French Revolution of 1789, the Dominican order was banned, and the friars forced to leave. In 1804 the conventual complex including the church became the property of the city of Toulouse, and in 1810 the emperor Napoleon requisitioned the church and converted it into a barracks. Floors were installed to create upper storeys for dormitories, while stables and an armoury occupied the ground floor. During the period the building served as a barracks, the stained glass windows were destroyed, and the medieval paintings in the choir were painted over with whitewash.[8]

Monument and museum

[edit]Citizens who were appalled at the destruction succeeded in 1861 in convincing the army to move to new barracks. In succeeding years, the building housed an exhibition of Arts and Industries (1865), served as a playground for the pupils of the nearby Lycée Fermat starting in 1872, and as a place to safely store treasures from the museums of Paris during World War I.[8]

Several periods of restoration work were undertaken over the course of the 20th century. In 1905 the floors installed by the army were removed; starting in 1923 blocked windows were uncovered and stained glass installed; between 1953 and 1963 the chapels were reconstructed; and between 1965 and 1974 the whitewash covering the medieval murals was removed. Today the building functions as a museum.[8]

Architecture

[edit]The round arch at the base of the south side is a vestige of the original romanesque church, while the three solid buttresses correspond to the double-nave layout of the interior which was retained as the church grew. Otherwise the Jacobins is considered a leader in the development of the Gothique méridional (Southern French Gothic) style. One of the most typical characteristics is the fact that it is constructed entirely of brick. Also characteristic is the style of the south wall between the buttresses. Each section consists of a tall Gothic ogival (pointed) arch with a small rose window at the top, and below that a lancet window. The spaces between the buttresses of the nave also show the same ogival arch, in which is set a tall, narrow triple-lancet window. There is hardly any decoration, which is considered to have been a conscious choice aimed at differentiating this church from the highly elaborate Gothic of northern France.[1][9]

The nave also served as a model in the development of Southern French Gothic architecture in presenting a very unified space. The double-nave layout, however, one side for the friars and the other for the congregation, turned out to be inconvenient and was not imitated, whereas the choice of columns to support the Gothic vaulted roof was. Each slender column, only 1.4 metres (4 feet 7 inches) in diameter for a height of 28 metres (92 feet), including 22 metres for the stone shaft (72 feet), supports eight of the ribs of the vaulted ceiling, and the six columns divide the nave into six bays. A seventh column continuing the same line supports the 22 ribs of the vaulted roof of the choir, the famous Palm Tree. This masterpiece is considered a precursor to the complex structures of the later Gothic.[1][9]

- Pictures

-

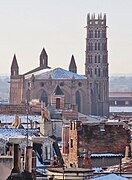

Southern French Gothic architecture (13th c.)

-

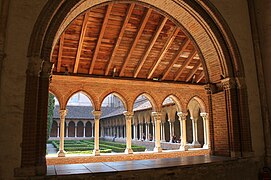

The cloister (14th c.)

-

The galleries of the cloister

-

The nave and its pillars (13th c.)

-

Vault of the church, 28 metres high (1275-1292)

-

The Palm Tree of the Jacobins (13th c.)

-

Reliquary of Thomas Aquinas

-

A keystone

-

The chapter hall

-

Chapel of Saint Antonin

-

The refectory

-

The bell tower

-

The church over the roofs

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Toulouse Église des Jacobins de

- ^ "Maison Pierre Seilhan". Retrieved 2022-09-05.

- ^ Le couvent des Jacobins Archived 2016-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cathar country", "About France"

- ^ Guiraud, Jean (1913). Saint Dominic. Digitized by Google Books 16 August 2007. Duckworth. Full text at archive.org

- ^ a b "La construction du couvent". Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Les reliques de Saint Thomas D´Aquin". Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ a b c "Un monument en peril; la période noire". Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ^ a b Couvent des Jacobins de Toulouse, Historique