Comic book convention

A comic book convention or comic con is a fan convention emphasizing comic books and comic book culture, in which comic book fans gather to meet creators, experts, and each other. Commonly, comic conventions are multi-day events hosted at convention centers, hotels, or college campuses. They feature a wide variety of activities and panels, with a larger number of attendees participating with cosplay than for most other types of fan conventions. Comic book conventions are also used as a method by which publishers, distributors, and retailers represent their comic-related releases. Comic book conventions may be considered derivatives of science-fiction conventions, which began during the late 1930s.

Comic-cons were traditionally organized by fans on a not-for-profit basis,[1] though nowadays most events catering to fans are managed by commercial interests for profit. Many conventions have award presentations relating to comics (such as the Eisner Awards, which have been presented at San Diego Comic-Con since 1988; or the Harvey Awards, which have been presented at a variety of venues also since 1988).

At commercial events, comic book creators often sign autographs for the fans, sometimes in exchange for a fixed appearance fee, and may sometimes draw illustrations for a per-item fee. Commercial conventions are usually quite expensive and are hosted in hotels. This represents a change for comic book conventions, which were traditionally more oriented toward comic books as a mode of literature, and maintained less differentiation between professional and fan.

The first official comic book convention was held in 1964 in New York City and was named New York Comicon.[2][3] Early conventions were small affairs, usually organized by local enthusiasts (such as Jerry Bails, known later as the "Father of Comic Fandom", and Dave Kaler of the Academy of Comic-Book Fans and Collectors), and featuring a few industry guests. The first recurring conventions were the Detroit Triple Fan Fair, which ran from 1965 to 1978, and Academy Con, which ran from 1965 to 1967. Many recurring conventions begin as single-day events in small venues, which as they grow more popular expand to two days, or even three or more every year. Many comic-cons which had their start in church basements or union halls now fill convention centers in major cities.[4]

Nowadays, comic conventions are big business, with recurring shows in every major American city. Comic book conventions in name only, the biggest shows include a large range of popular culture and entertainment elements of virtually all genres, including horror, animation, anime, manga, toys, collectible card games, video games, webcomics, and fantasy novels.

San Diego Comic-Con, a multigenre entertainment and comic convention held annually in San Diego since 1970, is the best known of U.S. comic-cons. According to Forbes, the convention is the "largest convention of its kind in the world";[5] and is also the largest convention held in San Diego.[6] According to the San Diego Convention and Visitor's Bureau, the convention has an annual regional economic effect of $162.8 million,[7][8] with a $180 million economic impact in 2011.[9] However, in 2017, SDCC lost its record of the largest annual multigenre convention to São Paulo's Comic Con Experience (first held in 2014).[10]

Internationally, the world's largest comic book convention, in terms of attendees, is Japan's Comiket (first held in 1975), which boasts an annual attendance of more than half a million people.[11] Italy's Lucca Comics & Games (first held in 1965) and France's Angoulême International Comics Festival (first staged in 1974) are the world's second and third largest comic festivals, respectively.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]In 1961 or 1962, Jerry Bails was vital for the formation of the Academy of Comic-Book Fans and Collectors (ACBFC), the first official organization of comic book enthusiasts and historians. The ACBFC brought fans of the medium together, administered the first industry awards, and assisted with the establishment of the first comic book conventions.

The academy's first order of business was to administer the Alley Awards, which traced their origin to "a letter to Jerry dated October 25, 1961", by fellow enthusiast (and future comics professional) Roy Thomas, in which he suggested to Bails that his fanzine Alter-Ego create its own awards to reward fandom's "favorite comic books in a number of categories" in a manner similar to the Oscars.[12] The first Alley Awards, given for the calendar year 1961, were reported in Alter Ego No. 4 (Oct. 1962).

Alley Talley and other gatherings of 1964

[edit]On March 21–22, 1964, the first annual "Alley Tally" by ACBFC members was organized by Bails at his house in Detroit, with the purpose of counting "the Alley Award ballots for 1963".[12] This became notable in retrospect as the first major gathering of comics fans, predating the earliest comic book conventions, which were held later in the year.[13] Attendees included Ronn Foss, Don Glut, Don and Maggie Thompson, Mike Vosburg, and Grass Green. Comics historian Bill Schelly notes that the Alley Tally and "even larger fan meetings in Chicago ... helped build momentum" for these earliest conventions.[12] (The Chicago gathering occurred May 9–10, 1964; it featured "several dozen" attendees, a dealer room, and film showings.)[14]

In addition, an unnamed convention held May 24, 1964, in the Hotel Tuller, Detroit, Michigan, was organized by teenagers Robert Brusch and Dave Szurek,[13][15] with assistance from Bails[12] and members of the Michigan Science Fiction Society.[16] This gathering featured about 80 fans of the comic book medium.[17]

New York Comicon

[edit]The first recorded "official" comic book convention occurred in 1964 in New York City. Known as the "New York Comicon",[2][3][18][19] it was held July 24, 1964,[14] at the Workman's Circle Building.[15] A one-day convention organized by 16-year-old Bernie Bubnis[20] and fellow enthusiast Ron Fradkin,[15] official guests of the Tri-State Con included Steve Ditko,[21] Flo Steinberg,[20] and Tom Gill.[15][22] Reports were of over 100 attendees.[22] A 16-year-old George R. R. Martin attended the convention and claimed to be the first person who signed up for the event.[23]

1965: The first recurring conventions

[edit]Continuing the momentum from the previous year, Bails, Shel Dorf, and the members of the Michigan Science Fiction Society formed the "organizing committee" of the multigenre convention Detroit Triple Fan Fair (DTFF),[24] which was held July 24–25, 1965 at the Embassy Hotel, in Detroit, Michigan.[12] The DTTF was held annually in Detroit until 1978.

Meanwhile, in New York City, teacher/comics enthusiast Dave Kaler[25] had taken over as ACBFC Executive Secretary; the organization produced Academy Con I (officially known as "Comi Con: Second Annual Convention of Academy of Comic-Book Fans and Collectors"),[26] held July 31 – August 1, 1965, at the Broadway Central Hotel.[27] With Kaler's management, the academy produced three successful "Academy Con" shows in New York during the summers of 1965–1967,[28][29][30] attracting industry professionals such as Otto Binder, Bill Finger, Gardner Fox, Mort Weisinger, James Warren, Roy Thomas, Gil Kane,[20] Stan Lee, Bill Everett, Carmine Infantino, and Julius Schwartz.[29] As befitting a convention run by the Academy of Comic-Book Fans and Collectors, the Alley Awards were presented at all three Academy Cons.[31] The 1965 Academy Con also featured one of the first recorded "superhero masquerades", or costume contests.

1965 also saw the genesis of what became the annual Italian comic book convention Lucca Comics & Games. Rinaldo Traini and Romano Calisi (forming the International Congress of Cartoonists and Animators) held the Salone Internazionale del Comics ("International Congress of Comics") in Bordighera.[32] In 1966, it was relocated to a small piazza in the center of Lucca, and has grown in size and importance over the years.

Expansion and growth

[edit]In 1966, comic book conventions continued to evolve and expand, The July 23–24 New York Comicon (not to be confused with the later New York Comic Con) was held at the Park Sheraton Hotel, in New York. Produced by John Benson,[29] guests included Jack Kirby, Jim Steranko, Otto Binder, Len Brown, Larry Ivie, Jack Binder, Roy Thomas, Gil Kane, Archie Goodwin, Bhob Stewart, Klaus Nordling, Sal Trapani, Rocke Mastroserio, and Ted White. (There were four women in attendance: Pat Lupoff, Lee Hoffman, Flo Steinberg, and Maggie Thompson.)[33] Featured events included a keynote speech by Kirby, a discussion about censorship between Don Thompson and Comics Code Authority acting administrator Leonard Darvin, a panel about the Golden Age of Comics, and one on the "so-called 'Forgotten '50s", particularly EC Comics. Bhob Stewart, on a panel with Archie Goodwin and Ted White, predicted that there would soon be "underground comics" just as there were already "underground films".[34]

That same summer (August 12–14) in New York, Dave Kaler produced Academy Con II at the City Squire Inn.[29]

Meanwhile, also in 1966, the first Southwesterncon was held in Dallas, Texas. Organized by Larry Herndon (of the fanzine Star Studded Comics), the official guest was Dave Kaler;[35] about 70 attendees participated. Later Southwesterncons rotated between Houston ("Houstoncon")[36] and Dallas ("D-Con"), adding Oklahoma City ("Multicon") to the mix in 1970.[37] The Southwesterncon partnership lasted roughly until 1971, with Houstoncon, D-Con, and Multicon continuing separately until 1982.

In 1966, a new convention, Gateway Con, was inaugurated in St. Louis.[38]

In 1968, two important conventions had their start. Taking over for the Academy Con, Brooklyn native and school teacher Phil Seuling hosted the International Convention of Comic Book Art at the Statler Hilton Hotel in New York City on July 4–7. The guests of honor were Stan Lee and Burne Hogarth[39] This annual convention, which later became known as the Comic Art Convention (CAC), hosted the presentation of the Alley Awards from 1968 to 1970.[31] CAC ran annually (occasionally in Philadelphia) over Independence Day weekend, until 1983. In England, Phil Clarke produced Comicon '68 (British Comic Art Convention) at the Midland Hotel, Birmingham, from August 30 to September 2, 1968. "Member"-guests include Alan Moore, Paul Neary, Jim Baikie, Steve Moore, and Nick Landau; there were 70 attendees.[13] The British Comicon ran annually, variously in Birmingham, London, and Sheffield, until 1981.

The 1970s and explosive growth

[edit]Comic book conventions increased dramatically during the 1970s, with many of the largest conventions of the modern era being established during the decade. During the early 1970s, conventions were initiated in almost every major American city (and some minor ones), as well as in London, with Comic Mart, a bimonthly trade show which ran regularly until the mid-1980s. Comic book creators, editors, and publishers began to make it part of their routine to attend conventions as official guests. Major comics-related news events were often revealed at annual conventions: examples include the news that Jack Kirby was defecting from Marvel to DC, and DC's announcement that it was reviving Captain Marvel.[40]

On August 1–3, 1970, Shel Dorf produced the Golden State Comic-Con, held at the U.S. Grant Hotel, in San Diego. Official guests were Forrest J. Ackerman, Ray Bradbury, Jack Kirby, Bob Stevens, and A. E. van Vogt, and it drew 300 people.[41] The three-day show evolved into San Diego Comic-Con, and now attracts 130,000 or more attendees.[42]

The Creation Convention debuted in 1971, organized by 14-year-old Queens schoolboys Adam Malin and Gary Berman,[43] and held over Thanksgiving weekend at the New Yorker Hotel, in New York City.[44][45] The guest of honor was Jim Steranko.[46] From that time until the late 1980s, Creation Entertainment continued producing large annual conventions in New York City, usually occurring the weekend after Thanksgiving.[47] A popular venue for the Thanksgiving cons was the Statler Hilton Hotel.[48] In the mid-1970s, attendance at the New York Creation conventions averaged around 5,000 fans; the admission was around $5/day.[49]

The 1971 Comic Art Convention (held July 2–4 at the Statler Hilton Hotel, New York City) was notable for being the convention credited by Will Eisner for his return to comics:

I came back into the field because of [convention organizer Phil Seuling]. I remember [him] calling me in New London, [Connecticut], where I was sitting there as chairman of the board of Croft Publishing Co. My secretary said, 'There's a Mr. Seuling on the phone and he's talking about a comics convention. What is that?' She said, 'I didn't know you were a cartoonist, Mr. Eisner.' 'Oh, yes,' I said, 'secretly; I'm a closet cartoonist.' I came down and was stunned at the existence of the whole world. ... That was a world that I had left, and I found it very exciting, very stimulating".[50]

Nostalgia '72, held July 22–23, 1972, at the Pick-Congress Hotel, was the first Chicago-area comics and collectibles convention.[45] Produced by Nancy Warner, the show had about 2,000 attendees.[51] That show evolved into the Chicago Comicon (now known as Fan Expo Chicago), and has been known to attract as many as 70,000 attendees annually.[52]

The Angoulême International Comics Festival debuted in Angoulême, France, in January 1974. 10,000 attendees[53] made it the most successful inaugural comic book festival to that date.[citation needed] 1974 also saw the first OrlandoCon, organized by regional chairman of the National Cartoonists Society Jim Ivey; guests included C. C. Beck, Roy Crane, Hal Foster, Ron Goulart, and Les Turner. OrlandoCon ran annually for 20+ years until 1994.

In 1976, there were 20 comic book conventions held throughout the United States; many of them attracted thousands of attendees. About this time specialized shows began being organized, emphasizing on such topics as so-called "underground comics",[13] EC Comics,[54] women in comics, and individual creators like Frank Frazetta.

In August 1979, FantaCo Enterprises publisher Thomas Skulan produced FantaCon '80 at The Egg convention center, Empire State Plaza, in Albany, New York. The first annual Albany-area horror and comic book convention,[55] FantaCon ran annually until 1990.

Creation Entertainment spreads its wings

[edit]Beginning about 1980, Creation Entertainment expanded its conventions beyond New York, producing cons in San Francisco[56] and Washington, D.C.[57] By 1983, the company was the main producer of comic book conventions nationwide.[58] For instance, in 1986, Creation produced large-scale comics conventions in at least six cities, including Philadelphia, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and New Brunswick, New Jersey. (The New York show featured a special tribute to Marvel Comics' 25th anniversary; guests included Stan Lee and Jim Shooter.)[59]

During this time, Creation branched out from comics and began producing conventions for the genres of horror and science fiction; it was known particularly for its Doctor Who conventions. After 1988, the company stopped producing comic book conventions to emphasize its other, more profitable, fan conventions.

The 1980s

[edit]Both the Heroes Convention and the multigenre Dallas Fantasy Fair debuted in 1982. HeroesCon is one of the largest independent comic book conventions still operating; during the heyday of the Dallas Fantasy Fair, it was one of the largest comics conventions in the country, third in attendance behind San Diego Comic-Con and the Chicago Comicon.[citation needed] (The Dallas Fantasy Fair went defunct in 1995.)

Comic book conventions spread to Canada and Switzerland in 1985; also debuting that year was the United Kingdom Comic Art Convention (UKCAC), first held September 21–22, 1985, at the University of London Union. Guests included such U.K. stars as Steve Bissette, Bill Sienkiewicz, Dave Sim, Marv Wolfman, Brian Bolland, John Bolton, Eddie Campbell, Alan Davis, Hunt Emerson, Brett Ewins, Dave Gibbons, Ian Gibson, Denis Gifford, Alan Grant, Garry Leach, David Lloyd, Mike McMahon, Alan Moore, Steve Moore, Paul Neary, Kevin O'Neill, Ron Smith, Dez Skinn, Bryan Talbot, and John Wagner. Admission was £7.50 for both days. UKCAC ran annually until 1998.

A number of still-extant conventions debuted in 1987, beginning with the Wonderful World of Comics Convention, held at the Oakland Convention Center, in Oakland, California. Later to be known as WonderCon, the convention was founded by San Jose native John Barrett, co-owner of the retail chain Comics and Comix. The multigenre Dragon*Con also debuted that year, hosted by the Pierremont Plaza Hotel, in Atlanta, Georgia. Official guests were Michael Moorcock (his first convention appearance in twelve years), Robert Asprin, Lynn Abbey, Robert Adams, Richard "Lord British" Garriott, Gary Gygax, and Toastmaster Brad Strickland; and there were 1,400 attendees.

In 1988, in commemoration of Superman's 50th anniversary, the Cleveland Convention Center hosted the International Superman Expo. Held June 16–19, official guests include Curt Swan, Jerry Ordway, George Pérez, Marv Wolfman, and Julius Schwartz.[60][61]

By the end of the 1980s, comic book conventions were evolving into sprawling affairs that promoted movies, television shows, celebrity performers, video games, toys, and cosplay as much as (if not more than) comic books. Many historians date this shift to the release of Tim Burton's movie Batman in 1989, which began the convention circuit's newfound enthusiasm for movies.[4]

Great Eastern fills a gap

[edit]Great Eastern Conventions produced comic book conventions for almost 20 years, but most actively during the years 1987–1996. In New York City, the Great Eastern shows filled the gap after the mid-1980s demise of the annual Comic Art Convention and Creation Conventions. From 1993 to 1995, Great Eastern hosted two New York City shows annually at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center. (The 1995 show was the last comic book convention held at the Javits Center until the New York Comic Con in 2006.)[citation needed] Great Eastern also ran shows in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts,[62] Oregon, Minnesota, Texas, and South Florida. Despite their large fan attendance and expansive venues, however, Great Eastern's large shows were criticized by many within the industry for pandering to dealers and spectacle. As frequent participant Evan Dorkin stated, "The New York shows are extremely unfriendly to both creators and fans. ... There is limited programming, limited professional appearances at these shows."[63]

In March 1996, Great Eastern, at a very late time, cancelled what had been advertised as a larger-than-usual New York show, scheduled to be held at the New York Coliseum on 59th St. & Columbus Circle.[63] As a substitute event, comic book retailer Michael Carbonaro and others quickly organized the first Big Apple Comic Con,[63] now a long-running show. Greenberg and Great Eastern Conventions disappeared from the fan convention circuit from that time.

Small press conventions and comic book "festivals"

[edit]In response to the big conventions' shifting of emphasis away from comic books themselves, a number of small conventions were organized during the mid-1990s that emphasized comics, particularly those not published by the big mainstream companies DC Comics and Marvel Comics. Many of these "indy cons" were inspired by Cerebus creator Dave Sim. In 1992, Sim partnered with Great Eastern Conventions in promoting small conventions in more than 20 U.S. locations,[64] including Indiana, Oregon, Texas, as well as in South Florida. And in 1995, Sim toured the country in a self-styled nine-stop "Spirits of Independence" tour.[65]

The antecedent to these new "comic festivals" may have been Berkeleycon 73, held April 20–22, 1973, at the Pauley Ballroom, ASUC Building, University of California, Berkeley. Berkeleycon was the first convention devoted to underground comix[45] (which had their unofficial mecca in the San Francisco Bay Area).

The first exclusively small press conventions were CAPTION, which debuted in Oxford, England, in 1992; the Alternative Press Expo (APE), which debuted in San Jose, California, in 1994; and the Small Press Expo (SPX), which premiered in Bethesda, Maryland in 1994.

Wizard dominates the 2010s; con wars

[edit]Wizard Entertainment purchased the Chicago Comicon in 1997 to expand from its core publishing business into trade/consumer conventions.[66] The renamed "Wizard World Chicago" was the template for a new kind of convention that shifted its emphasis from actual comic books to ancillary elements of popular culture fandom: celebrity performers, movies, television, video games, and toys – "comic conventions" almost in name only.[4] By 2006, Wizard World Chicago boasted a weekend attendance of more than 58,000 people.[67]

In 2002, Wizard produced "Wizard World East" in Philadelphia,[68] a still-ongoing show (now known as "FanExpo Philadelphia"). The company added ongoing shows in Texas in 2003, Los Angeles in 2004,[69] and Boston in 2005. In 2007–2008, Wizard held conventions in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Texas.[70]

Beginning in 2009, Wizard made a concerted push to dominate the North American convention circuit. The company began by starting new shows in various cities, and then by acquiring existing conventions,[71] such as New York City's longest-running multigenre popular culture convention, the Big Apple Convention,[72][73] and the Paradise Comics Toronto Comicon.[74][75][76]

Wizard's 2010 "North American Comic Con" tour included shows in Toronto, Anaheim,[77] Philadelphia,[78] Chicago, New York City, Austin, and Boston.[79] As part of a "major offensive against Reed Exhibitions' New York Comic Con," Wizard scheduled "three East Coast shows in a row — the New England Comic-Con in Boston on October 1-3, Big Apple the same weekend, and the new New Jersey Comic-Con the weekend after, on October 15-17."[80] This was the beginning of what came to be known as the "Con Wars": in fact, Wizard originally scheduled the 2010 Big Apple Comic Con for October 7–10, the exact same dates as the previously scheduled 2010 New York Comic Con.[81][82] After a public outcry, Wizard moved the dates of its 2010 New York convention to October 1–3.[80][82] (Ultimately, the "Wizard World New York Experience" conventions were not successful; the company omitted New York entirely in 2012 and gave up the New York market after 2013.)

In 2013, Wizard produced conventions in 13 cities,[83] expanding to 20 in 2014.[84]

This increase of Wizard-produced conventions resulted in accusations that the entertainment behemoth was deliberately trying to cause its competitors to fail.[85][86] However, many praised Wizard's professional and standardized method of producing conventions.[4]

In 2015, however, Wizard lost $4.25 million in revenue and cut back from 25 to 19 convention events in 2016.[87] By 2018, the company was producing thirteen annual conventions around the U.S.[88]

The COVID-19 pandemic harmed the convention business worldwide. Most 2020 conventions scheduled for after mid-March of that year were canceled,[89] and many were displayed online only in 2021. Wizard World had only six in-person conventions in 2021,[90] and that August the company announced it would be selling the convention events business to FanExpo, with the final Wizard World Chicago show occurring in October.[91][92][90]

Conventions as big business

[edit]Starting during the mid-2000s, ongoing comic book conventions were organized in most major U.S. cities, most of which are still ongoing. [See List of comic book conventions] These pop-cultural gatherings attract tens of thousands of fans and generate millions of dollars in revenue every year.[4] In addition to the Wizard-run conventions, Comic-Con International runs San Diego Comic-Con, WonderCon, and formerly ran the Alternative Press Expo; while Reed Exhibitions runs the New York Comic Con and the Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo.

Types

[edit]Since the first conventions during the mid-1960s, hundreds of local and regional comic book conventions have been organized around the world either as one-time or annual events. At these conventions, fans of comic books come together with the professional writers, artists, editors, and publishers of the business to discuss its many aspects. Increasingly, comic conventions have expanded in scope to encompass the gamut of popular culture phenomena relating to comics, from movies, television, and animation to gaming and collectibles. Some cities have a number of comic-cons. Nearly every weekend of the year now has at least one convention somewhere, and some conventions are held on holiday weekends where four or more days can be devoted to events.

Commercial shows vs. volunteer conventions

[edit]An important distinction can be made between commercial events (often called "shows") – those managed by dedicated companies who specialize in convention organization, or by local for-profit businesses – and volunteer-run conventions.

Usually run for profit, commercial events tend to charge for "tickets" or "admission" rather than having "memberships". A primary emphasis of commercial events is meeting celebrities, such as actors of television shows and movies, professional wrestlers, glamour models, etc. There are frequently very long lines of people waiting for autographs at commercial events. While famous actors like William Shatner of Star Trek are paid tens of thousands of dollars per convention, minor and obscure bit players pay to set up booths to sell autographs and memorabilia.[93] Commercial events also tend to have less small-scale programming; panels will more often be composed of famous actors, directors, etc. on press junkets, where the panels are held in very large rooms with very high attendance. The largest conventions (in terms of attendance) tend to be commercial ones. Commercial events are more likely to be about popular visual media than volunteer cons, and they also tend to attract many younger people, but this is not absolute by any means. Some commercial conventions have been known to harass fan-run conventions via their legal teams.[86]

Volunteer conventions, however, tend to be smaller in scope and more intimate in character. Although there are frequent autograph sessions, they tend to be less of an attraction for volunteer cons. Admission to volunteer cons is usually termed "membership", thus emphasizing that the fans themselves are the ones who compose the convention, rather than the staff who manage commercial cons. A community of fans who run such conventions has developed, and many of them share their best practices and keep convention-running traditions alive.[40]

Comics festivals and "indy shows"

[edit]So-called "comics festivals" are based on a European model started by such long-running conventions as Lucca Comics & Games and the Angoulême International Comics Festival. Festivals emphasize the art and literature of the comics form, and only minimally related popular culture and merchandising. In the U.S., comics festival and "indy shows" tend to emphasize the "alternative comics" genre, not the work of "mainstream" publishers like DC Comics and Marvel Comics. Cosplaying is rarely if ever a feature of these conventions. Some notable North American small press conventions include:

- Alternative Press Expo (APE), San Jose, California (1994–2017) – produced in San Francisco for 15 years

- Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC), Columbus, Ohio (2015–present)

- Chicago Alternative Comics Expo (CAKE), Chicago, Illinois (2012–present)

- Comic Arts Brooklyn (CAB) (formerly known as Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Fest [BCGF]), Brooklyn, New York (2009–present) – produced by the retailer Desert Island Comics

- Comic Expo (Bristol International Comic & Small Press Expo), Bristol, England (2004–2014) – produced by retailer Mike Allwood

- East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention (ECBACC), Philadelphia (2002–present) – focuses on black creators and characters

- Massachusetts Independent Comics Expo (MICE), Boston, Massachusetts (2010–present)

- MoCCA Festival, New York City (2002–present) – originally produced by the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art; now produced by the Society of Illustrators

- Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (SPACE), Columbus, Ohio (2000–present) – Produced by small-press publisher Back Porch Comics

- Small Press Expo (SPX), Bethesda, Maryland (1994–present)

- STAPLE!, Austin, Texas (2005–present)

- Stumptown Comics Fest, Portland, Oregon (2004–2013)

- Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF), Toronto (2003–present) – produced by the retailer The Beguiling

- Legion Comic Book, Toy and Art Convention Smyrna, Georgia (2019–present) produced by Urbnpop Productions

"Comics-only" shows

[edit]Comics-only conventions emerged in response to the sprawling popular culture-emphasizing conventions epitomized by Wizard Entertainment, San Diego Comic-Con, and the New York Comic Con. "Comics-only" shows tend to hearken back to the comic book conventions of the 1970s and 1980s: still emphasizing the genres of superhero, fantasy, horror, and crime; as well as dealers selling back issues and other collectibles, but without the domineering presence of the mainstream publishers, or movie and television producers. Notable "comics-only" conventions include:

- Baltimore Comic-Con (est. 2000 in Baltimore, Maryland)

- Big Apple Comic Con (est. 1996 in New York City)

- Heroes Convention (est. 1982 in Charlotte, North Carolina)

Organization and staffing

[edit]Comic book conventions were traditionally managed and staffed by volunteers,[94] though venues may require certain activities to be contracted out. Event funding typically relies on convention registrations.[95] Nowadays, many of the larger conventions are incorporated as non-profit organizations, usually to achieve tax-exempt status and safeguard the organizers' personal assets – in the USA, some are 501(c)(3) charities, while others are registered as recreational clubs. The largest events may require as many as a hundred volunteers.[citation needed] Volunteers often receive T-shirts or other benefits.

Timing and duration

[edit]Most comic book conventions occur during a weekend, with events scheduled between Friday evening and Sunday afternoon. Saturday is typically the busiest day, as most fans must return home on Sunday. One-day passes are sometimes sold at a reduced price.

Reasons for this include:

- Most fans would have to take a vacation from work or study to attend an event held during the workweek.

- Transportation costs are often lower for weekend travelers.

- Hotels have few business travelers during the weekend, making it much easier to reserve a block of rooms and secure space for programming at a reduced price. Many fans are students and have little discretionary income, so hotel and convention fees are important factors.[96][97]

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, both WonderCon and Dragon Con were canceled, and San Diego Comic-Con moved its programming online.[98]

Anatomy of a typical convention

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2016) |

Although wide variations exist between different conventions, there is a general pattern to which most adhere.

Attendees

[edit]Attendees include artists and dealers offering products and services for sale to fans, and those who wish to buy them. Others come for the programming, or to meet friends or other comic book fans in general. Many attend for all of these reasons. Some later publish a "con report" detailing their experiences.

Attendees of major conventions receive a bag with the convention program, a lavishly illustrated volume featuring themed artwork, articles submitted by members and the official guests, along with a description of the event's programming, staff, rules, guests, and any charity being supported by the convention.[99][100] Local restaurant information and a combination pocket schedule and map may also be included. Sponsors often receive additional items such as T-shirts, pins, or ribbons, as well as faster registration badge pick-up and on-site meals.[101] They may also be displayed prominently in convention publications.

Official guests

[edit]Comic book conventions typically feature official guests or guests of honor. A convention may have as many guests of honor as the convention committee wishes. A guest can be an industry person – some notable and frequently appearing examples of industry guests include Stan Lee, George Pérez, and John Byrne. More and more, guests also can include movie and television directors and actors, as more of these cultural products are based on comic books. Examples of this sort of guest, participating frequently with the convention circuit, include William Shatner, Bruce Campbell, and Norman Reedus. Comic conventions represent an opportunity for fans to interact with such individuals that may not be possible outside the event.[4]

Professionals at conventions

[edit]Conventions provide a forum for fans to see first-hand and meet their favorite authors and artists. They also serve the interests of authors, editors, and other publishing professionals, providing opportunities for networking, promotion, and a convenient location for contract negotiations and other business meetings.

A number of cons include a category for "Attending Professionals": professionals who pay a (possibly reduced) price to enter but also get a special name badge that proclaims them to be professionals in the field.[citation needed]

During the early days of comic book conventions, there was little or no distinction made between the "pros" and the "fans". (After all, many professionals began as fans, and may still consider themselves fans; and more than a few fans have also worked professionally or semi-professionally in the field.) Nowadays, other than in the so-called "Artist Alleys", there is more of a caste system among professionals and enthusiasts.

Artist Alley

[edit]Artist Alley is a fixture at most comic conventions. It is an area where creators display and sell their work (including original art), take commissions, sign autographs, and interact with fans. These areas may also include crafts, drawn art, self-published books or video, fanzines, and more.

Con suite

[edit]At North American conventions, a hospitality suite is often provided as a room reserved for minor refreshments, quiet conversation, and a place to rest briefly. The refreshments typically include coffee, tea, juice or soda, and light meals appropriate for the time of day. Depending on local liquor distribution and liability laws, the suite may serve alcohol. At conventions in the rest of the world, the hotel or convention center bar typically offers the same social function. At conventions in the United Kingdom, the provision of cask ale is generally considered essential.

Cosplay

[edit]Traditionally, conventions held a costume contest called a masquerade, where persons go on stage and compete for nominal prizes based on their skill in assembling and presenting genre-inspired outfits. This, however, would be more accurately labelled a "talent show" rather than the "fancy dress ball" that the term suggests (although British fandom sometimes uses the term "fancy dress").

From press coverage of comic book and anime conventions has arisen the widespread tendency of fans in general attendance at the con to dress as their favorite characters in elaborate costumes (known as cosplay) that are time-consuming and/or expensive to assemble.

Weapons policies

[edit]At some conventions, attendees carry costume props that appear to be weapons. To forestall concerns about misuse of real weapons at such events, the security team "peace-bonds" anything that might look like a weapon.[102] (Peace-bonding is a conspicuous lock, tie, or mark which makes or identifies something unusable, such as a weapon, and shows that the owner's intentions are purely peaceful.)

The event's "weapons policy" may offer objective criteria to determine what looks like a weapon. For example, a weapons policy may require a peace-bond for anything that a reasonable person might recognize as a weapon from a short distance in dim light. Real weapons, if allowed, are disabled, secured, and marked. For example, bright orange zip ties may be used to hold a sword in a scabbard or to hold a pistol in a holster. Simulated or costume props may require conspicuous marks, such as bright ribbons or zip ties, to show that security has deemed them safe to be carried. Simulated weapons or props which can be used as a weapon may be disabled or secured in the way as real weapons. Peace-bonding helps security control the use or abuse of real weapons at a convention or other event: anything that looks like a weapon but which is not peace-bonded is immediately deemed to be suspicious.

Programming

[edit]

Panel-led discussions, or Panels, usually fill up the daytime hours of most conventions with typically one-hour discussions involving some pre-determined topic, usually related in at least some way to comics. Panels usually come in two segments: the host puts on a presentation or does an interview with a guest, and then the fans are asked to give questions. The topic scope for panels is varied and can include things from new releases to author spotlights.

There are also workshops, that are like panels but are more geared towards instructions through a major or specific task such as how to draw comics, or use industry-specific software. Another event at most comic book conventions include screenings of movies and TV shows that can last through the day.

Panel members (even professionals) are not customarily paid for their appearance, although many North-American conventions waive membership fees for program participants or rebate them after the convention.

Special events

[edit]Some conventions feature award ceremonies, in which the best works and most notable individuals are recognized for their contributions to the field. [See Awards, below]

A convention may have one or more auctions. The Art Auction is an event where the most popular items from the art show are sold to the most interested buyers at the convention. Many conventions also have auctions for charities.

Evening entertainment often includes a combination of official and unofficial events, including formal invitational dinners, and fandom-themed room parties.

A few conventions and festivals have a closing ceremony to formally mark the end of the convention. Depending on the convention, this can be a major gathering of most of the membership, or it may be lightly attended or dispensed with entirely as members are occupied with packing up and checking out of the hotel.

Exhibits and fixed functions

[edit]An exhibit hall or dealers' room is a popular feature at comic book conventions. Publishing companies, distributors, and other proprietors often arrive to exhibit and/or sell their newest products to fans. Wares can include back issues of comic books, graphic novels and trade paperbacks, manga and anime media, action figures, apparel or pre-made costumes, music CDs, software, decorations, toys, art books, specialty foods, and many more.

Many conventions have video rooms in which genre-related audiovisual presentations occur, typically commercial Hollywood movies, genre television show episodes, and anime. If there are multiple media rooms, each one may have themed content. Larger conventions may also have a genuine movie room, for presentation of actual movies on film instead of video.

Game rooms are also available at some conventions for attendees to play a variety of genre games, including collectible card games, role-playing games board games, and video games.

Thematic Areas

[edit]

Thematic areas are set up in the comics fairs where cosplayers and visitors can take photographs in an environment that imitates that of a specific comic, anime or video game or participate in various themed activities. These areas are set up by not for profit associations or sometimes by video game developers or Anime producers. Some examples of these areas are those dedicated to Star Wars, Fallout or to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Idiosyncrasy

[edit]Many con-goers take pride in being interesting and unusual, and many conventions are idiosyncratic. Cons often have activities, running jokes, organizational methods, and other features that not only differentiate them from other cons but are often a point of pride. Most cons vary from the above outline in one or more important ways, and many have their own unique characteristics. Most cons will tend to evolve many of their own idiosyncrasies in this manner. To fans, these are often part of the charm each convention offers.[citation needed]

Awards

[edit]Almost since their inception, comic book conventions have hosted comic awards. Two of the longest-running and most prestigious awards are the Eisner Award and the Harvey Award, both of which began in 1988 after the dissolution of the Kirby Awards. The Eisner Award has been presented at San Diego Comic-Con since 1988; while the Harvey Awards, also inaugurated in 1988 and after being presented at many different venues for much of their life, have been presented at the Baltimore Comic-Con since 2006. The following is a list of conventions and the award presentations they host (or formerly hosted):

Angoulême International Comics Festival (France)

- Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême (1974–present) – formerly known as the "Alfreds" (1974–1988) and "Alph-Art Awards" (Prix Alph-Art) (1989–2003). In addition, the Angoulême festival presents a number of other awards called "The Official Awards of the International Comics Festival" (le Palmarès Officiel du Festival international de la bande dessinée). from a pool of 40–60 albums, called "official selections." From these are awarded the "Best Album" prize, five "Angoulême Essentials," one "Revelation Essential" (given to new talent), and one Essential chosen by the public. The Heritage Essential (for reprinted material) and Youth Essential are selected from separate nominee pools.

Baltimore Comic-Con (U.S.)

- Harvey Award (2006–2016)

- Ringo Award (2017–present)

Barcelona International Comics Convention (Spain) – Gran Premi del Saló (1988–present)

Chicago Comicon (U.S.) – Harvey Award (1988)

Comics Fest India (India) – Kalpana Lok Awards (2010–present)

Dallas Fantasy Fair (U.S.) – Harvey Award (1989–1995)

East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention (U.S.) – Glyph Comics Awards (2006–present)

Festival de la BD francophone de Québec (Canada) – Prix Bédéis Causa (1988–present)

Forest City Comic Con (Canada) – Joe Shuster Awards (2015)

Heroes Convention (U.S.) – Inkwell Awards (2011–present)

International Comics Show of Erlangen (Germany) – Max & Moritz Prize (1984–present)

Lucca Comics & Games (Italy) – Gran Guinigi Award (1967–present)

MoCCA Festival (U.S.)

- Harvey Award (2004–2005)

- MoCCA Arts Festival Awards of Excellence (2012–present)

Pittsburgh Comicon (U.S.) – Harvey Award (2000–2002)

Salón Internacional del Cómic del Principado de Asturias (Spain) – Haxtur Award (1985–present)

San Diego Comic-Con (U.S.)

- Inkpot Award (1974–present)

- Russ Manning Award (1982–present)

- Kirby Award (1985–1987)

- Eisner Award (1988, 1991–present)

- Bill Finger Award (2005–present)

Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (U.S.) – Day Prize/SPACE Prize (2001–present)

Small Press Expo (U.S.) – Ignatz Award (1997–present)

Strip Turnhout (Belgium) – Bronzen Adhemar (1972–present)

Supanova Pop Culture Expo (Australia) – Ledger Award (2005–present)

Toronto Comic Arts Festival (Canada) – Doug Wright Award (2005–present)

Toronto Comic Con (Canada) – Joe Shuster Awards (2005)

WonderCon (U.S.) – Harvey Award (1997–1999)

Defunct awards

[edit]United States

[edit]- Alley Award – presented at Academy Con (1965–1967)[31] and Comic Art Convention (1968–1970)[21]

- Comics Buyer's Guide Fan Awards – presented at Chicago Comicon (1983–1996)[103]

- Don Thompson Award – presented at Motor City Comic Con (1992–1998)

- Goethe Awards/Comic Fan Art Awards – presented at Comic Art Convention (1971–1974)

- Howard E. Day Prize – presented at Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (S.P.A.C.E.) (2001–2007)

- Ignatz Award (not the same Ignatz Award presented at the Small Press Expo) – presented at OrlandoCon (1975–1994)

- Klein Award – presented at MoCCA Festival (2002–2012)

- Lulu Award – presented at San Diego Comic-Con (1997–2007),

MoCCA Festival (2008–2009), and the Long Beach Comic Con (2010)

- Wizard Fan Awards – presented at Dragon Con (1993), Philadelphia Comic Book Spectacular (1994),[104] and Wizard World Chicago (1995–2006)

United Kingdom

[edit]- Ally Sloper Award – presented at Comics 101 (1976)

- Eagle Awards – presented at British Comic Art Convention (1977–1979), London Comic Mart (1983), Birmingham Comic Art Show (1984, 1986), United Kingdom Comic Art Convention (UKCAC) (1987–1990), Comic Festival (2000, 2002), Comic Expo (2004, 2006–2008), London MCM Expo (2010–2012), and London Film and Comic Con (Eagles rebranded as "True Believer Comic Awards") (2014)

- National Comics Awards – presented at United Kingdom Comic Art Convention (UKCAC) (1997–1998) and Comic Festival (1999, 2001–2003)

- British Comic Awards – presented at the Thought Bubble Festival (2012–2016)

Italy

[edit]- Lucca Comics & Games – Yellow Kid Awards (1970–2005)

Timeline of New York City comic book conventions

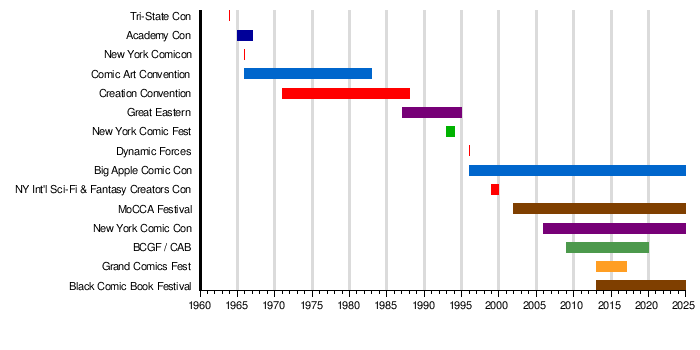

[edit]New York City has had a checkered history with comic book conventions. It was the first U.S. city to host a convention (the 1964 "Tri-State Con"), but was poorly served for conventions from the late 1980s until the mid-to-late 1990s – despite both major mainstream comic publishers, DC Comics and Marvel Comics, being headquartered in New York during that time. Presently, New York is flush with comic book conventions, with at least five annual shows being produced. The following is a timeline of New York City comic book conventions.

Timeline of British comic book conventions

[edit]England has hosted comic book conventions since 1968 (the British Comic Art Convention), but until the early 2000s had trouble sustaining any one recurring show. As of 2024, England is host to four long-running, large annual conventions – the MCM Comic Con London (est. 2002), the London Film and Comic Con (est. 2004), the Thought Bubble Festival (est. 2007), and The Lakes International Comic Art Festival (est. 2013).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Siegel, Howard P. "Made in America," BEM #16 (Dec. 1977): "These early conventions were run by purists for panelologists, and not meant to be commercially overbearing or expensive to go to."

- ^ a b Ballman, "The 1964 New York Comicon: The True Story Behind the World's First Comic Book Convention (The 1960s: The Silver Age of Comic Conventions) (Volume 1)"

- ^ a b History Channel, "Superheroes Decoded: Comic-Con | History"

- ^ a b c d e f Babka, Allison. "Wizard World Inc.: A roving comic con looks to corner the geek market," The Riverfront Times (April 3, 2014).

- ^ David M. Ewalt (July 25, 2011). "The Coolest Costumes of Comic-Con". Forbes. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Peter Rowe (July 16, 2009). "Invasion of the comic fanatics". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

While the Con's impact is global, it's San Diego's single largest convention, drawing more than 100,000 people who will rent hotel rooms, order meals and buy bagfuls of whatnots, all to the tune of $32 million.

- ^ "Comic-Con kicks off with freaks, fans, famous people". The Baltimore Sun. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Tom Blair (July 15, 2011). "Comic-Con is truly one in the millions". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Peter Rowe (April 22, 2013). "Beer is big, bubbly business in SD, new study confirms". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

That same year, the direct economic impact of Comic-Con – a five-day pop culture celebration that is the county's largest convention – was pegged at $180 million.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Rosario, Mariana; Rosset, Tatiane (December 1, 2017). "Comic Con Experience se firma como maior evento do tipo no mundo". VEJA SÃO PAULO (in Portuguese).

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Schelly, Bill. "Jerry Bails' Ten Building Blocks of Fandom," Alter Ego vol. 3, No. 25 (June 2003), pp. 5–8.

- ^ a b c d Skinn, Dez. "Early days of UK comics conventions and marts," Archived February 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine DezSkinn.com. Accessed March 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Gabilliet 2010, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 183.

- ^ Cooke, Jon B. "Rich Buckler Breaks Out! The Artist on Deathlok, T'Challa, and Other Marvel Tales," Comic Book Artist Collection, Volume 3 (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2005).

- ^ "Historian Collects Comics: They Are Works of Art," Detroit News (1965).

- ^ Schelly, Bill. "1966: The Year of THREE* New York Comicons!," Alter-Ego No. 53 (Oct. 2005).

- ^ Schelly 2010, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Schelly 2010.

- ^ a b Gabilliet 2010.

- ^ a b Q, Shathley. "The History of Comic Conventions," PopMatters (June 17, 2009).

- ^ "George R.R. Martin was the first person to sign up for the first ever Comic Con". Sky HISTORY TV channel. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Fantasy literature, fantasy films, and comic art,": Detroit Triple Fan Fair program book (Detroit Triple Fan Fair, 1972).

- ^ Newsday (November 4, 1965).

- ^ White, Wallace (August 13, 1965). "ComiCon". Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. p. 23.

- ^ Thomas, Roy. "Splitting the Atom: More Than You Could Possibly Want to Know About the Creation of the Silver Age Mighty Mite!" The Alter Ego Collection, Volume 1 (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2006), p. 99.

- ^ Schelly 2010, p. 8, "Introduction".

- ^ a b c d Schelly, Bill. "The Kaler Con: Two Views: Bigger And Better Than The Benson Con Just Three Weeks Before?? (Part VIII of '1966: The Year Of (Nearly) Three New York Comics Conventions')," Alter-Ego #64 (Jan. 2007).

- ^ RBCC Rocket's Blast Comicollector #52 (1967).

- ^ a b c Gabilliet 2010, p. 250–251.

- ^ "Lucca 9," Bang! No. 11 (1974), p. 55.

- ^ Helioscope PDX (March 27, 2021). Women who made a huge impact in comics - Friends of Lulu. YouTube.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (November 2005). "1966: The Year of THREE (Or Maybe 21/2) New York Comicons!: Part 2: The 1966 New York 'Benson' Con". Alter Ego. No. 54.

- ^ Schelly 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Rouner, Jef (June 12, 2014). "Comicpalooza: How Houston's Comics Convention Came Back from the Dead to Become One of the Best in the Country". Houston Press.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (September 2019). "Comic Fandom Archive: BART BUSH, Then And Now – Part 2: Continuing Our Talk With The Co-Founder of OAF: (The Oklahoma Alliance Of Fans)". Alter Ego. No. 160. p. 69.

- ^ "Nation Wide St. Louis' Comic Art Con (advertisement)". Rocket's Blast Comicollector. No. 45. 1966.

- ^ Schelly 2010, p. 107.

- ^ a b Siegel, Howard P. "Made in America," BEM #17 (Feb. 1978).

- ^ Comic-Con Souvenir Book No. 40 p.61 (2009).

- ^ Hill, Kyle (July 21, 2014). "San Diego Comic-Con: By The Numbers". Nerdist. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ "The Comic Book Conventions: The humble beginnings...continued...," Creation Entertainment website. Accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ Pinaha, Bob. "Creation '71 No Turkey!" Comic Fandom Monthly (Jan. 1971), pp. 4–7.

- ^ a b c Beerbohm, Robert. "Update to Comics Dealer Extraordinaire Robert Beerbohm: In His Own Words," Comic-Convention Memories (June 24, 2010).

- ^ "The Comic Book Conventions: The humble beginnings...," Creation Entertainment website. Accessed June 4, 2012.

- ^ Grant, Steven. "Permanent Damage: Issue #43," Comic Book Resources (July 10, 2002).

- ^ Fratz, Doug. "TNJ Listings," The New Nostalgia Journal No. 28 (Aug. 1976), p. 39.

- ^ Cummings, Judith. "Comic Book Collectors Take Funnies Seriously," The New York Times (November 26, 1977).

- ^ Groth, Gary (May 2005). "Will Eisner: Chairman of the Board". The Comics Journal. No. 267. Archived from the original on March 20, 2011.

- ^ Yates, Ronald (July 23, 1972). "Nostalgia Show Here a Pageant of the Past". Chicago Tribune. p. a14.

- ^ Isaacs, Deanna (April 15, 2010). "Clash of the Comic Cons: Wizard World and the new C2E2 battle it out for the hearts and minds of local comics fans". Chicago Reader.

- ^ Jennings, Dana. "The Angouleme Convention," The Comics Journal No. 89 (Mar. 1984), p. 100.

- ^ Ayres, Bruce. "The EC Convention Report," The Vault of Mindless Fellowship No. 2. (Wildwood Press, Ltd., 1972), pp. 8–10, 28.

- ^ Green, Roger. "FantaCon 2013: the Tom Skulan interview," Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine "Information Without The Bun," TimeUnion.com (February 7, 2013).

- ^ Cooke, Jon B. (January 2002). "The Art of Arthur Adams". Comic Book Artist (17). TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013.

- ^ Mastrangelo, Joseph P. "Browsing for Comic Books," The Washington Post (June 29, 1981).

- ^ Thomas, Michael "Reining in a Dark Horse: An Interview with Diana Schutz". Comic Book Resources. December 20, 2001. Accessed March 17, 2008

- ^ "Comic Book Conventions 1986," Star Brand No. 2 (Nov. 1986), p. 18.

- ^ "Summer Comic Conventions," The Comics Journal No. 122 (June 1988), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Myers, Greg W. "It Was 10 Years Ago: Cleveland's International Superman Expo — June 16–19, 1988," Comics Buyer's Guide (July 17, 1998), p. 8, 10.

- ^ Doten, Patti. "Comics convention a real draw," The Boston Globe (Jan 21, 1995), p. 23.

- ^ a b c "Newswatch: NYC Comics Convention Cancelled, Fans Irate," The Comics Journal #185 (Mar. 1996), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hibbs, Brian. "Blood & Thunder: Who Bears the Burden: Retailer or Publisher," The Comics Journal #148 (Feb. 1992), p. 7.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi. "Have your CAKE in Chicago next June," The Beat (Aug, 18, 2011): "Chicago being one of the original stops** on the Spirits of Independence tour that launched the entire indie comics show experience."

- ^ "Wizard Magazine Buys Chicago Comicon". News Watch. The Comics Journal. No. 195. April 1997. p. 24.

- ^ "Wizard World Chicago Sets Attendance Records". Raving Toy Maniac - The Latest News and Pictures from the World of Toys (Press release). Congers, New York: www.toymania.com. August 7, 2006.

- ^ Atchison, Lee (June 2002). "Wizard World East". Sequential Tart.

- ^ "Wizard Announces Successful Debut for Wizard World Los Angeles". Diamond Comic Distributors, Inc. (Press release). 2004. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (November 1, 2006). "Wizard World 2007 and 2008 Tour Schedule". The Beat.

- ^ Kwan, Steven (November 3, 2010). "Third annual Tucson Comic Con". Arizona Daily Wildcat. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (April 8, 2009). "Shamus buys Big Apple Con". The Beat.

- ^ "April 9: Wizard Entertainment CEO Acquires Big Apple Con". The Comics Journal. No. 299. August 2009. p. 22.

- ^ Armitage, Hugh (June 25, 2009). "Wizard CEO buys Toronto Comicon". Digital Spy.

- ^ "Wizard's Gareb Shamus Buys Toronto Comicon". Comic Book Resources. June 24, 2009.

- ^ "GAREB SHAMUS, WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CEO, BUYS TORONTO COMICON" (Press release). Paradise Comics. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010.

- ^ CBR News Team, ed. (July 16, 2009). "Wizard Announces Anaheim Comic-Con for 2010". comicbookresources.com (Press release).

- ^ "Philly Wizard World Photo Gallery Now Open!". Dread Central. October 4, 2012.

- ^ Pate, Brian (January 7, 2010). "Wizard World Comic Con Tour Plans Return to Texas in 2010". Convention Scene. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi (May 18, 2010). "Con wars: Shamus retreats, moves Big Apple". The Beat.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (October 16, 2009). "Breaking: Big Apple to go head to head with New York Comic-Con next year". The Beat. Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on February 20, 2010.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi (October 19, 2009). "Big Apple/Con Wars wrap-up". The Beat.

- ^ "Wizard World Comic Cons". Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (September 17, 2013). "Wizard World adds seven cities including Tulsa, Sacramento, and San Antonio". The Beat.

- ^ "Matt Fraction on HeroesCon/Wizard World". Comic Book Resources. July 22, 2005.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi (August 13, 2013). "Con Wars in Minneapolis as Wizard World schedules show two weeks before Spring Con". The Beat.

- ^ Griepp, Milton (April 19, 2016). "WIZARD WORLD LOSES $4.3 MILLION IN 2015". ICv2.

- ^ "Form 10-K: WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT, INC". United States Securities and Exchange Commission. Washington, D.C. December 31, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (September 11, 2020). "New York Comic Con Goes Metaverse: With in-person events on hold for the past six months, virtual conventions are evolving". The Beat. Publishers Weekly.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi (August 10, 2021). "Fan Expo acquires six Wizard World comic cons for 2022: Fan Expo will take over Chicago, Philadelphia, Portland and three other shows". The Beat.

- ^ Ridgely, Charlie (August 10, 2021). "Wizard World Sells Its Comic Con Events to Fan Expo". ComicBook.com. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Salkowitz, Rob (August 10, 2021). "Fan Expo Acquires 6 Wizard World Events Including Chicago, Building Global Fan Con Juggernaut". Forbes. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Reitman, Valerie (April 8, 2005). "'Star Trek' Bit Players Cling On". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ Evanier, Mark (July 8, 2007). "Report from Pittsburgh". Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2007.

- ^ Guidestar.org – see Anthrocon, Anthropomorphic Arts and Education, Midwest Furry Fandom and the Oklahoma Association of Anthropomorphic Arts

- ^ University of California, Davis Department of Psychology (May 5, 2007). "Furry Survey Results". Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ Parry, Laurence "GreenReaper" (May 5, 2007). "UC Davis posts furry survey results". WikiFur News. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ Lyman, Paige (July 25, 2020). "Comic-Con Is Online, and So Is the Artist Alley". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Anthrocon (March 29, 2006). "Anthrocon Convention Book Submission Guidelines". Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2006.

- ^ Anthrocon 2006 convention book

- ^ Anthrocon (March 29, 2006). "Anthrocon Registration". Archived from the original on January 12, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2006.

- ^ Rogow, Roberta (1991), Futurespeak: A Fan's Guide to the Language of Science Fiction, New York: Paragon House, p. 244, ISBN 9781557783479.

- ^ "Comic Buyers Guide Fan Awards". Hahn Library. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "Greenhill Sues Great Eastern and Wizard". Newswatch. The Comics Journal. No. 172. November 1994. p. 40.

Sources

[edit]- Duncan, Randy; Smith, Matthew J (2009). The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul (2010). Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Translated by Bart Beaty; Nick Nguyen. University of Mississippi Press.

- McCarthy, Helen (2006). 500 Manga Heroes & Villains. Chrysalis Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7641-3201-8.

- Schelly, Bill (2010). Founders of Comic Fandom: Profiles of 90 Publishers, Dealers, Collectors, Writers, Artists and Other Luminaries of the 1950s and 1960s. McFarland.

External links

[edit] Wikinews attends ComiCon in Tyler, Texas at Wikinews

Wikinews attends ComiCon in Tyler, Texas at Wikinews- 1960s Comic Conventions from the pages of Rocket's Blast Comicollector — comic convention news and advertisements from the 1960s