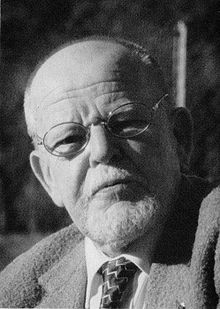

Claude Ballif

Claude Ballif | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 22, 1924 Paris, France |

| Died | July 24, 2004 (aged 80) Saint-Dizier, France |

| Era | Modernist, Western avant-garde |

Claude Ballif (22 May 1924 – 24 July 2004) was a French composer, writer, and pedagogue.[1] He worked at a number of institutions throughout more than 40 years of teaching, one of which he had attended as a student.[2] Among his pupils were Raynald Arseneault, Nicolas Bacri, Gérard Buquet, Joseph-François Kremer, Philippe Manoury, Serge Provost, Mehmet Okonsar,[citation needed] Simon Bertrand,[3] Alexandre Desplat,[4] and Claude Abromont.[5] He was described as a French modernist and as "the product of the exciting and turbulent post World War II years of the Western avant-garde" alongside composers Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[6][7]

Biography

[edit]Ballif was born in Paris on 22 May 1924, the fifth of ten children.[8][9][10][2] He grew up in a bourgeois family but did not recognize the privilege of his childhood as a rarity until much later.[11] His mother Odette was from the Festugière family, forgemasters and owners of the Château de Poissons in Haute-Marne.[12][11] Her brother was André-Jean Festugière and her first cousin was George Desvallières.[11] Ballif's father, Colonel Laurent Ballif, was a senior military officer who served in the Tibesti War, World War I, and World War II.[11] Laurent was of Swiss descent.[11] Ballif started music at an early age; though the piano was his first love, he was told piano was for girls and that his fingers would never be able to make the right positions, so he learned violin.[11][10][2]

When Ballif was 13, his father was assigned to a base in Madagascar and the family moved to Antananarivo.[11][13] While in Madagascar, "Captain Durand," an artillery director on base, taught Ballif music theory; he took violin lessons from a beggar.[11] He also learned the play the djembe, the valiha, and the flute.[11] The family returned to France while Ballif was still in high school and he started at the Conservatoire de Bordeaux in 1942 at 18.[13][2][11] He left in 1948 to attend the Conservatoire de Paris with Aubin and Messiaen as his teachers and Alain Weber, Michel Fano, and Jean-Michel Defaye as his classmates.[11] He dropped out in 1951 before finishing his degree because he did not feel that he could properly express himself with the academic constraints on the students' music.[2][11][13][8] In 1954, he was awarded a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) grant that allowed him to study at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin.[1][13] Blacher and Rufer were among his teachers.[13][1][11] He spent three summers in Germany, particularly at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, where he met Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono, and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[9][13] He also interpreted the Darmstadt Summer Courses for John Cage, who did not speak German.[1][11]

He performed the music for film advertisements for a while and in 1959 started at the Groupe de Recherche Musicale with Pierre Schaeffer.[11][1][2] Ballif's friend Hélène Boschi worked at École Normale de Musique de Paris and told him of an opening for a teacher of music history, analysis, and pedagogy.[11][8] Not long after, he married Elisabeth,[citation needed] the daughter of an army general.[11] In 1965, he helped establish the music department at Paris 8 University Vincennes-Saint-Denis and in 1971 was appointed to succeed Messaien, his former teacher, at the Conservatoire de Paris.[12][9] He also taught at the Regional Conservatory of Reims and as a visiting professor at McGill University in Montréal.[6][2][8] He left the Conservatoire de Paris in 1990.[2] He subsequently taught in Sevran for ten years before visiting Venezuela with Williams Montesinos and Austin Marianu in July 2000.[11] What was intended to be a short trip stretched out for months and Ballif settled there because he was "able to do what I dreamed of when I was 16... just be a composer".[11] He taught lessons on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, and spent the rest of his time at his piano.[2][13][11]

During his career, he published the following books: Introduction à la métatonalité (1956), Berlioz (1969), Voyage de mon oreille (1979), Souhaits etre Symboles (1988; published only in Canada), and L'Habitant du labyrinthe : entretiens avec Alain Galliari (1992).[14][9] He also founded the Ivan Wyschegradsky Association in 1983.[15]

Ballif spent the final years of his life living in Haute-Marne at the Château de Riaucourt, which had been passed down to him by his maternal grandfather.[10] He died on 24 July 2004 in Saint-Dizier and is buried in Poissons.[8][2] His mother died two days later, age 104.[12]

Metatonality

[edit]Metatonality, "a fusion of diatonic scales with the chromatic one, which form[s] an 11-element metatonal scale", was invented by Ballif in 1949.[8][12][2] He struggled in his early years of music study with balancing his need for independent creation and the university's regimented music lessons.[1] This is what led him to leave the Conservatoire de Paris without a completed degree in 1951.[12][1] Ballif published his first book about metatonality (Introduction à la métatonalité) in 1956.[1] He credits his "deep friendship" with Jean Wahl, Josef Rufer, Andréas Rónaï, and Pierre Schaeffer for solidifying the concept and practice of metatonality very early on.[2] He added referential and orient concepts to his theory as well.[16] He became interested in microtonal theory after meeting Ivan Wyschnegradsky for the first time; Wyschnegradsky and Alois Hába "launched [him] into the ultrachromatic universe."[16][6][1]

Ballif wrote his doctoral dissertation on metatonality.[8] His music was also deeply influenced by his staunch Catholicism.[6]

Awards

[edit]| Year | Award | Awarding body | Country | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | Composition Competition | Geneva International Music Competition | Switzerland | [9] |

| 1974 | Arthur Honegger Prize | Fondation de France | France | [12][9] |

| 1975 | Prix Florent Schmitt | Académie des Beaux-Arts | France | [17][12] |

| 1984 | Chevalier | Ordre des Arts et des Lettres | France | [14][12] |

| 1986 | SECAM Grand Prix | Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique | France | [12][14] |

| 1991 | Officier | Ordre national du Mérite | France | [14] |

| 1994 | Commandeur | Ordre national du Mérite | France | [14][12] |

| 1999 | Grand prix national de la musique | The City of Paris | France | [14][12][18] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tosi, Michèle (2005-03-25). "Claude Ballif [1924–2004]" (in French). ResMusica. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Claude Ballif, l'imaginaire à l'œuvre" (PDF) (in French). Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris. 2018. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ "Simon Bertrand (1969–)". QUASAR4. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ Tsioulcas, Anastasia (2011-07-18). "Alexandre Desplat: Creating Color For Harry Potter". wbur. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ Tosi, Michèle (2022-01-20). "L'harmonie en question, par Claude Abromont et Eugène de Montalembert" (in French). ResMusica. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ a b c d "Ode To Gravity: The Music of Claude Ballif". radiOM. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ Kaptainis, Arthur (1992-11-27). "Classical". Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Retrieved 2022-02-06 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The death of Claude Ballif". Times of Malta. 2004-08-12. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ a b c d e f Culver, Andrew (1979-05-19). "Claude Baliff: Excited like a fly". Montreal Star. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Retrieved 2022-02-06 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Juillet 2004 : décès du musicien Ballif". La voix de la Haute-Marne (in French). 2020-02-08. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Claude Ballif" (in French). Institut national de l'audiovisuel. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "De juillet 2004 à décembre 2004" (in French). Le Panthéon des musiciens. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Toutes les actualités portrait: Claude Ballif" (in French). Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Lyon. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f "Claude Ballif (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- ^ Fernández Guerra, Jorge (2014-11-23). "Wyschnegradsky, descubrir a un pionero de la música del siglo XX". Doce Notas (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ a b "« Un délire de dédales », Rencontre avec Claude Ballif". ETVDES Revue de Culture Contemporaine (in French). 2004-05-01. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ "Prix Florent Schmitt: Listing of Prizewinning Composers and Recordings: 1963-2020". FlorentSchmitt.com. n.d. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ "Huit lauréats". Le Monde (in French). 1980-12-10. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- 1924 births

- 2004 deaths

- 20th-century French classical composers

- 20th-century French male musicians

- Academic staff of the Conservatoire de Paris

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Commanders of the Ordre national du Mérite

- Conservatoire de Bordeaux alumni

- Conservatoire de Paris alumni

- French male classical composers

- Microtonal composers

- Composers from Paris

- Sociétaires of the Comédie-Française

- Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin alumni

- Academic staff of the École Normale de Musique de Paris

- Academic staff of McGill University

- People from Haute-Marne

- Educators from Paris