Ottomar Anschütz

Ottomar Anschütz | |

|---|---|

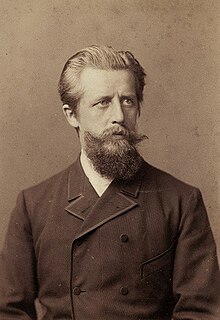

Anschütz, 1886 | |

| Born | 16 May 1846 |

| Died | 20 May 1907 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Photography |

Ottomar Anschütz (16 May 1846, in Lissa – 30 May 1907, in Berlin) was a German inventor, photographer, and chronophotographer.[1]

He is widely seen as an early pioneer in the history of film technology. At the Postfuhramt in Berlin, Anschütz held the first showing of life sized pictures in motion on 25 November 1894.[2]

Career

[edit]Anschütz studied photography between 1864 and 1868 under the well-known photographers Ferdinand Beyrich (Berlin), Franz Hanfstaengl (Munich) and Ludwig Angerer (Vienna). He received recognition for his photograph of John of Saxony on horseback in 1867. He then took over his father's company in Lissa, mainly working as a portrait photographer and as a decorative painter.[3][4]

Anschütz made his first instantaneous photographs in 1881. He developed his portable camera that allowed shutter speeds as short as 1/1000 of a second in 1882. He made a name for himself with sharp photographs of imperial military demonstrations in Breslau in 1882 and gained more fame with pictures of flying white storks (Ciconia ciconia) in 1884 — the first photographs of birds in the wild.[5] He organized exhibitions of his work at the Berlin Kriegsakademie and the Düsseldorf Kunsthalle. In 1885, Anschütz started working on chronophotography, leading to very successful exhibitions of motion pictures with his Electrotachyscope from 1887 onward (see below). Anschütz made pictures of the firing of cannonballs at 76 millionths of a second with a shutter that he patented on 11 November 1888 as the Brennebenen-Verschluß, marketed in cameras by C.P. Goerz & Co for almost 30 years. Anschütz designs at least three different camera models for the company in collaboration with Carl Paul Goerz.[3]

Anschütz moved to Berlin in 1888 and opened a studio at Charlottenstr. 59.[3]

Motion picture work

[edit]Anschütz started making chronophotographs of horses with 12 cameras in 1885, sponsored by the Prussian minister of Culture. He continued the motion studies of horses with 24 cameras under assignment of the Ministry of War at Königlichen Militärreitinstitut (Royal Military Institute) in Hannover during 1886, resulting in over one hundred series of sequential photographs.[3] The quality of his pictures was generally regarded to be much higher than that of the chronophotography works Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey. The works that these pioneers had published by then showed not much more than silhouettes, while Anschütz' pictures had a much more natural gradient.[6]

In 1886, Anschütz developed the Electrotachyscope, an early device that displayed short motion picture loops with 24 glass plate photographs on a 1.5 meter wide rotating wheel that was hand-cranked to the speed of circa 30 frames per second. Each image was illuminated by a sparking spiral Geissler tube and displayed on a small opal glass window in a wall in a darkened room for up to seven spectators. Different versions were shown at many international exhibitions, fairs, conventions and arcades from 1887 until at least 1894. From 1890 onward, Anschütz also demonstrated a coin-operated cylindrical Electrotachyscope with six small viewing screens. Starting in 1891, some 152 examples of a coin-operated peep-box Electrotachyscope model were manufactured by Siemens & Halske in Berlin and sold internationally.[3][9][4] It was used in a public arcade and was displayed at the International Electrotechnical Exhibition in Frankfurt. Nearly 34,000 people paid to see it at the Berlin Exhibition Park in summer 1892. Others saw it in London or at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

On 25 November 1894, Anschütz introduced a Electrotachyscope projector with a 6x8 meter screening in Berlin. Between 22 February and 30 March 1895, a total of circa 7,000 paying customers came to view a 1.5-hour show of some 40 scenes at a 300-seat hall in the old Reichstag building in Berlin.[10]

Awards

[edit]- Bronze medal at the 1883 photographic exhibition in Brussels[3]

- Vermeille medal from the Photografischen Gesellschaft in Wien on 14 January 1887 (for his series of systematic instantaneous photography)[11]

- Silver medal at the 1889 Photographischen Jubiläumsausstellung in Berlin[3]

- Honorary diploma at the July 1891 photographic exhibition in Brussels.[12]

- Gold medal at the 1900 Photographischen Ausstellung in Berlin[3]

Legacy

[edit]Anschütz' 1884 albumen photographs of storks inspired aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal's experimental gliders in the late 1880s.[13]

Anschütz' many international motion picture exhibitions between 1887 and 1894 probably inspired many other pioneers in the history of film technology. Although there's no discrete evidence, Georges Demenÿ most likely saw Anschütz' "Sprechende Porträts" before developing his Phonoscope in 1891. Edison or his employees may have seen the Electrotachyscope (in New York possibly as early as 1887)[3] and their peep-box Kinetoscope machines were probably influenced by the Siemens & Halske type of Electrotachyscope.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ottomar Anschütz". Europeana Collections. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- ^ "Ottomar Anschütz, Kinogeschichte, lebender Bilder, Kino, erste-Kinovorführung, Kinovorführung, Projektion, Kinoe, Bewegungsbilder".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "O. Anschütz". Uni Trier (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ a b "Ottomar Anschütz, Elektrischer Schnellseher, Kino, Vorführgerät,Reihenaufnahmen, lebende Bilder, lebende Photographien, Geißlerische Röhre". www.ottomar-anschuetz.de. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Cox, Rosamund Kidman, ed. (2014). Wildlife Photographer of the Year: Portfolio 24. Firefly Books. p. 13. ISBN 9780565093426.

- ^ Rossell, Deac. "The Exhibition of Moving Pictures before 1896".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Ottomar Anschütz, Kinogeschichte, lebender Bilder, Kino, erste-Kinovorführung, Kinovorführung, Projektion, Kinoe, Bewegungsbilder".

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EArkp5YYTLA

- ^ Rossell, Deac. "The Anschuetz Zoetropes".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Ottomar Anschütz, Kinogeschichte, lebender Bilder, Kino, erste-Kinovorführung, Kinovorführung, Projektion, Kinoe, Bewegungsbilder". www.ottomar-anschuetz.de. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Photographische Korrespondenz. Getty Research Institute. Darmstadt : Helwich. 1887.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Ottomar Anschütz, Trommelschnellseher, Kino, Elektrischer-Schnellsehr, lebende-Bilder, Serienbilder". www.ottomar-anschuetz.de. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Lukasch, Bernd. "Lilienthal and Photography". Otto Lilienthal Museum. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

External links

[edit]- Ottomar Anschütz at Who's Who of Victorian Cinema

- "Schnellseher" and "Electrotachyscope"

- Collections with photographs taken by Ottomar Anschütz

- Photography of storks and moving pictures of the flight of a crane in his "Schnellseher" (quick-viewer)

- Photographs of Lilienthal's flights in 1893/94

- Goerz Photographing Experiments and the first flight of Otto Lilienthal

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.