Ernest Everett Just

Ernest Everett Just | |

|---|---|

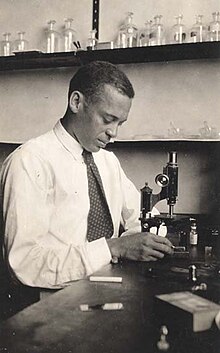

Just in 1925 | |

| Born | 14 August 1883 |

| Died | 27 October 1941 (aged 58) Washington D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Lincoln Memorial Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College University of Chicago |

| Known for | marine biology cytology parthenogenesis |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal (1915) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biology, zoology, botany, history, and sociology |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Frank R. Lillie |

Ernest Everett Just (August 14, 1883 – October 27, 1941) was a pioneering biologist, academic and science writer. Just's primary legacy is his recognition of the fundamental role of the cell surface in the development of organisms. In his work within marine biology, cytology and parthenogenesis, he advocated the study of whole cells under normal conditions, rather than simply breaking them apart in a laboratory setting.

Early life and education

[edit]Born to Charles Just Jr. and Mary (Matthews) Just on August 14, 1883, Just was one of five children. His father and grandfather, Charles Sr., were builders. When Just was four years old, both his father and grandfather died (the former of alcoholism).[1] Just's mother became the sole supporter of Just, his younger brother, and his younger sister. Mary Matthews Just taught at an African-American school in Charleston to support her family. During the summer, she worked in the phosphate mines on James Island. Noticing that there was much vacant land near the island, Mary persuaded several black families to move there to farm. The town they founded, now incorporated in the West Ashley area of Charleston, was eventually named Maryville in her honor.[2]

When Just was young, he became severely sick for six weeks with typhoid. Once the fever passed, he had a hard time recuperating, and his memory had been greatly affected. He had previously learned to read and write, but now had to relearn. His mother had been very sympathetic in teaching him, but after a while she gave up.[3]

Hoping Just would become a teacher, at the age of 13 his mother sent him to the "Colored Normal Industrial Agricultural and Mechanical College of South Carolina", the only 1890 land grant school for the education of Negroes in South Carolina, later known as South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Believing that schools for blacks in the south were inferior, Just and his mother thought it better for him to go north. At the age of 16, Just enrolled at the Meriden, New Hampshire, college-preparatory high school Kimball Union Academy. During Just's second year at Kimball, he returned home for a visit only to learn that his mother had been buried an hour before he arrived.[3] Despite this hardship, Just completed the four-year program in only three years and graduated in 1903 with the highest grades in his class.[4]

Just went on to graduate magna cum laude from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, class of 1907.[5] There, Just developed an interest in biology after learning about fertilization and egg development.[6] Just won special honors in zoology, and distinguished himself in botany, history, and sociology as well. He was also honored as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[4]

Just was a candidate to deliver a commencement speech, but was not chosen because the faculty "decided it would be a faux pas to allow the only black in the graduating class to address the crowd of parents, alumni, and benefactors. It would have made too glaring the fact, that Just had won just about every prize imaginable,"[3] including honors in botany, sociology, and history.[6] While teaching at Howard University, Just earned a PhD in 1916 from the University of Chicago, becoming the first African American to do so.[7]

Founding of Omega Psi Phi

[edit]On November 17, 1911, Ernest Just and three Howard University students (Edgar Amos Love, Oscar James Cooper, and Frank Coleman), established the Omega Psi Phi fraternity on the campus of Howard. Love, Cooper, and Coleman had approached Just about establishing the first black fraternity on campus. Howard's faculty and administration initially opposed the idea of establishing the fraternity, fearing that it could pose a political threat to Howard's white administration. However, Just worked to mediate the controversy and, despite the initial doubts, Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Chapter, was chartered on Howard's campus on December 15, 1911. Omega Psi Phi was incorporated under the laws of the District of Columbia on October 28, 1914.[1]

Career

[edit]When he graduated from Dartmouth, Just faced the same problems all black college graduates of his time did: no matter how brilliant they were or how high their grades were, it was almost impossible for black people to become faculty members at white colleges or universities. Just took what seemed to be the best choice available to him and accepted a teaching position at historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1907, Just first began teaching rhetoric and English, fields somewhat removed from his specialty. By 1909, however, he was teaching not only English but also Biology.[8] In 1910, he was put in charge of a newly formed biology department by Howard's president, Wilbur P. Thirkield and, in 1912, he became head of the new Department of Zoology, a position he held until his death in 1941.

Not long after beginning his appointment at Howard, Just was introduced to Frank R. Lillie, the head of the Department of Zoology at the University of Chicago. Lillie, who was also director of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, invited Just to spend the summer of 1909 as his research assistant at the MBL. During this time and later, Just's experiments focused mainly on the eggs of marine invertebrates. He investigated the fertilization reaction and the breeding habits of species such as Platynereis megalops, Nereis limbata, and Arbacia punctulata. For the next 20 or so years, Just spent every summer but one at the MBL.

While at the MBL, Just learned to handle marine invertebrate eggs and embryos with skill and understanding, and soon his expertise was in great demand by both junior and senior researchers alike.[9] In 1915, Just took a leave of absence from Howard to enroll in an advanced academic program at the University of Chicago. That same year, Just, who was gaining a national reputation as an outstanding young scientist, was the first recipient of the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, which he received on February 12, 1915. The medal recognized his scientific achievements and his "foremost service to his race."[3]

He began his graduate training with coursework at the MBL: in 1909 and 1910 he took courses in invertebrate zoology and embryology, respectively, there. His coursework continued in-residence at the University of Chicago. His duties at Howard delayed the completion of his coursework and his receipt of the Ph.D. degree.[9] However, in June 1916, Just received his degree in zoology, with a thesis on the mechanics of fertilization. Just thereby became one of only a handful of blacks who had gained the doctoral degree from a major university. By the time he received his doctorate from Chicago, he had already published several research articles, both as a single author and a co-author with Lillie.[8] During his tenure at Woods Hole, Just rose from student apprentice to internationally respected scientist. A careful and meticulous experimentalist, he was regarded as "a genius in the design of experiments."[10] He had explored other areas including: experimental parthenogenesis, cell division, cell hydration and dehydration, UV carcinogenic radiation on cells, and physiology of development.[6]

Just, however, became frustrated because he could not obtain an appointment at a major American university. He wanted a position that would provide a steady income and allow him to spend more time with his research. Just's scientific career involved a constant struggle for an opportunity for research, "the breath of his life". He was condemned by racism to remain attached to Howard, an institution that could not give full opportunity to ambitions such as the ones Just had due to budgetary constraints of the era.[9] Nevertheless, Just was able to make significant contributions to his field during this period, including co-authoring the textbook General Cytology, first published in June 1924, with other pioneers in cell biology, including Clarence Erwin McClung, Margaret Reed Lewis, Thomas Hunt Morgan and Edmund Beecher Wilson.[11] In 1929, Just traveled to Naples, Italy, where he conducted experiments at the prestigious zoological station "Anton Dohrn".

Then, in 1930, he became the first American to be invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin-Dahlem, Germany, where several Nobel Prize winners carried out research. Altogether from his first trip in 1929 to his last in 1938, Just made ten or more visits to Europe to pursue research. Scientists treated him like a celebrity and encouraged him to extend his theory on the ectoplasm to other species.[9] Just enjoyed working in Europe because he did not face as much discrimination there in comparison to the U.S. and when he did encounter racism, it invariably came from Americans.[3] Beginning in 1933, when the Nazis began to take the control Germany, Just ceased his work there. He moved his European-based studies to Paris and to the marine laboratory at the French fishing village of Roscoff, located on the English Channel.

Just authored two books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Animals (1939) and The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939), and he also published at least seventy papers in the areas of cytology, fertilization and early embryonic development.[12] He discovered what is known as the fast block to polyspermy; he further elucidated the slow block, which had been discovered by Fol in the 1870s; and he showed that the adhesive properties of the cells of the early embryo are surface phenomena exquisitely dependent on developmental stage.[13] He believed that the conditions used for experiments in the laboratory should closely match those in nature; in this sense, he can be considered to have been an early ecological developmental biologist.[14] His work on experimental parthenogenesis informed Johannes Holtfreter's concept of "autoinduction"[15] which, in turn, has broadly influenced modern evolutionary and developmental biology.[16] His investigation of the movement of water into and out of living egg cells (all the while maintaining their full developmental potential) gave insights into internal cellular structure that is now being more fully elucidated using powerful biophysical tools and computational methods.[17][18][19][20] These experiments anticipated the non-invasive imaging of live cells that is being developed today. Although Just's experimental work showed an important role for the cell surface and the layer below it, the "ectoplasm," in development, it was largely and unfortunately ignored.[3][21] This was true even with respect to scientists who emphasized the cell surface in their work. It was especially true of the Americans; with the Europeans, he fared somewhat better.[9]

Personal life

[edit]On June 12, 1912, he married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel. The two divorced in 1939.[6] That same year, Just married Hedwig Schnetzler, who was a philosophy student he met in Berlin.[6]

In 1940, Just was imprisoned by German Nazis, but was easily released thanks to the help of his wife's father.[6]

Death

[edit]At the outbreak of World War II, Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, researching the paper that would become Unsolved Problems of General Biology. Although the French government requested foreigners to evacuate the country, Just remained to complete his work. In 1940, Germany invaded France, and Just was briefly imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp. With the help of the family of his second wife, a German citizen, he was rescued by the U.S. State Department and he returned to his home country in September 1940. However, Just had been very ill for months prior to his encampment and his condition deteriorated in prison and on the journey back to the U.S. In the fall of 1941, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died shortly thereafter.[22]

Legacy

[edit]Just was the subject of the 1983 biography Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. The book received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.[23][24] In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Just.[25]

Beginning in 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has hosted the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage non-white students to pursue careers in biomedical sciences and health professions.[26] In 2008, a National Science Foundation-funded symposium honoring Just and his scientific work was held on the campus of Howard University, where he was a faculty member from 1907 until his death in 1941. Many of the speakers at the symposium contributed papers to a special issue of the journal Molecular Reproduction and Development dedicated to Just that was published in 2009.

Since 1994, the American Society for Cell Biology has given an award[27] and hosted a lecture in Just's name. At least two of the institutions with which Just was associated have established prizes or symposia in his name: The University of Chicago Archived 2018-09-07 at the Wayback Machine,[28] where Just received his PhD (in zoology, in 1916), and Dartmouth College, where he received his undergraduate degree. In 2013, an international symposium honoring Just was held at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy, where Just had worked starting in 1929.[29][30][31][32]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.[33] A children's book about Just, titled The Vast Wonder of the World: Biologist Ernest Everett Just, written by Mélina Mangal and illustrated by Luisa Uribe, was published by Millbrook Press in November 2018.

Just believed that "life as an event lies in a combination of chemical stuffs exhibiting physical properties; and it is in this combination, i.e., its behavior and activities, and in it alone that we can seek life.".[34] He also wrote: "[L]ife is the harmonious organization of events, the resultant of a communion of structures and reactions",[13] and "We [scientists] have often striven to prove life as wholly mechanistic, starting with the hypothesis that organisms are machines! Living substance is such because it possesses this organization--something more than the sum of its minutest parts"[35] He argued forcefully that the "ectoplasm," the outer region of the cytoplasm, and not the nucleus, constitutes the heart of the dynamic cell. He was convinced that the surface of the egg cell possesses an "independent irritability," which enables the egg (and all cells) to respond productively to diverse stimuli.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b The Capital Region Ques[usurped], accessed March 14, 2013.

- ^ Donna Jacobs, "A BIT ON MARYVILLE - The People, Trials, and Tribulations of one of Charleston's first black enclaves" Archived 2013-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Manning, Kenneth R. (1983). Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195034981.

- ^ a b Ernest Just Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, Black Inventor Museum. Accessed October 11, 2009.

- ^ Kelsey, Elizabeth. "Expansive Vision, Ahead of His Time: Dartmouth celebrates biologist E. E. Just, Class of 1907". Dartmouth Life. Dartmouth College. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ernest Everett Just". Biography. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ "Future Intellectuals: Ernest Everett Just (PhD 1916)". University of Chicago. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Lee, Edward (March 2006). "Ernest Everett Just". Blacfax: 15–16.

- ^ a b c d e Lillie, Frank (1942). "Obituary". Science. 95 (2453): 10–11. doi:10.1126/science.95.2453.10. PMID 17752140.

- ^ Jeffery, William R. (1983), "Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941): a dedication. Biological Bulletin 165: 487.

- ^ Chambers, Robert; Conklin, Edwin G.; Cowdry, Edmund V.; Jacobs, Merkel H.; Just, Ernest E.; Lewis, Margaret R.; Lewis, Warren H.; Lillie, Frank R.; Lillie, Ralph S.; McClung, Clarence E.; Mathews, Albert P.; Morgan, Thomas H.; Wilson, Edmund B. (1925). Cowdry, Edmund V. (ed.). General Cytology: A Textbook of Cellular Structure and Function for Students of Biology and Medicine (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226251257. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Ernest Everett Just". San Jose State University Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b Just, E. E. (1939), The Biology of the Cell Surface. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son and Co., Inc.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; William R. Eckberg (2006). "Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941)--an early ecological developmental biologist". Dev. Biol. 296 (1) (August 1, 2006), pp. 1–11.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm (2009) Ernest Everett Just, Johannes Holtfreter, and the origin of certain concepts in embryo morphogenesis. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 912-921

- ^ Kirschner, M. W.; J. C. Gerhart (2005), The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin's Dilemma. New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ Just, E. E. (1939), "Water" In: The Biology of the Cell Surface. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son and Co., Inc., pp. 124–146.

- ^ Charras, G. T.; T. J. Mitchison; L. Mahedevan (2009), "Animal cell hydraulics". J. Cell Sci. 122 (18): 3233–3241.

- ^ Needleman, D.; J. Brugues (2014), "Determining physical principles of subcellular organization". Dev. Cell 29: 135–138.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; Stuart A. Newman (2014), "Ernest Everett Just: Egg and Embryo as Excitable Systems". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B (Molecular and Developmental Evolution) 322 (4): 191–201.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (1988), "Cellular politics: Ernest Everett Just, Richard B. Goldschmidt, and the attempt to reconcile embryology and genetics". In: Rainer R., D. Benson, J. Maienschein (eds), The American Development of Biology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 311–346.

- ^ Byrnes, W. Malcolm; Eckberg, William R. (2006). "Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941)—An early ecological developmental biologist". Developmental Biology. 296 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.445. PMID 16712833.

- ^ "Pulitzer for Fiction Won by Author of 'Ironweed'". The Spokesman-Review. April 16, 1984. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Garland E. Allen (November 1998). "Life Sciences in the Twentieth Century". History of Science Society. Archived from the original on 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Dr. Ernest E. Just Honored on New Black Heritage Stamp". Jet. February 26, 1996. p. 19.

- ^ Shantae D. James (March 20, 2003). "Summary Statement of the 3rd Annual Ernest E. Just Symposium". Medical University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on September 15, 2006. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ "E.E. Just Lecture Award" Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, ASCB.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ L. Santella & JT. Chun, "International Symposium - The dynamically active egg: The legacy of Ernest Everett Just" Archived 2014-09-04 at the Wayback Machine, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli, 13 maggio 2013.

- ^ Cristina Zagaria, "Just, biologo afroamericano che trovò la libertà a Napoli", La Repubblica, 11-05-2013.

- ^ W. Malcolm Byrnes, "Walking in the Footsteps of Ernest Everett Just at the Stazione Zoologica in Naples: Celebration of a Friendship", Howard University, May 15, 2013.

- ^ W. Malcolm Byrnes, Sulle orme di E.E. Just alla Stazione Zoologica di Napoli: celebrazione di un'amicizia Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, researchitaly, 01/07/2013.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002), 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Just, Ernest Everett (1988). The Biology of the Cell Surface (Facsimile ed.). New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0824013806.

- ^ Just, E. E. (1933), "Cortical cytoplasm and evolution". Am. Nat. 67: 20–29.

- ^ Newman, Stuart A. (2009), "E. E. Just's 'independent irritability' revisited: The activated egg as excitable soft matter" Archived 2016-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 966–974.

Further reading

[edit]- Manning, Kenneth R., Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Manning, Kenneth R. (2009), Reflections on E. E. Just, Black Apollo of Science, and the experiences of African American scientists. Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 897–902.

- Sapp, Jan (2009), "'Just in time': Gene theory and the biology of the cell surface". Molecular Reproduction and Development 76 (11): 903–911.

- Crow, James F. (2008), "Just and Unjust: E. E. Just (1883-1941)". Genetics 179: 1735–1740.

- Grantham, Shelby (1983), "The Greatest Problem in American Biology..." Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Volume 76, No. 3 (November 1983): 24–31.

- Grunwald, Gerald B. (2013), "A Century of Cell Adhesion: From the Blastomere to the Clinic Part 1: Conceptual and Experimental Foundations and the Pre-Molecular Era". Cell Communication and Adhesion 20: 127–138.

- Gilbert, Scott F. (1988), "Cellular politics: Ernest Everett Just, Richard B. Goldschmidt, and the attempt to reconcile embryology and genetics". In: Rainger, R., D. Benson, J. Maienschein (eds), The American Development of Biology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 311–346.

- Esposito, Maurizio (2013), Romantic Biology, 1890–1945. London: Pickering and Chatto. See especially pp. 134–143.

- Gould, S. J. (1985), "Just in the middle: A solution to the mechanist-vitalist controversy". In: The Flamingo's Smile: Reflections in Natural History. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., pp. 377–391.

- Gould, S. J. (1987), "Thwarted genius". In: An Urchin in the Storm: Essays About Books and Ideas. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., pp. 169–179.

- Cohen, S. S. (1986). "Balancing science and history: a problem of scientific biography. "Black Apollo of science: the life of Ernest Everett Just." By Kenneth R. Manning. Essay review". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. Vol. 8, no. 1. pp. 121–8. PMID 3534923.

- Dummett, C O (1985). "Unexpected historical peregrinations". The Journal of the American College of Dentists. Vol. 52, no. 2. pp. 28–31. PMID 3897332.

- Wynes, C E (1984). "Ernest Everett Just: marine biologist, man extraordinaire". Southern Studies. Vol. 23, no. 1. pp. 60–70. PMID 11618159.

- Brown, Mitchell, "Faces of Science: African-Americans in the Sciences" Archived 2006-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, 1996.

- Kessler, James, J. S. Kidd, Renee Kidd, and Katherine A. Morin, Distinguished African-American Scientists of the 20th Century. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1996.

- McKissack, Patrick and Frederick. African-American Scientists. Brookfield, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, 1994.

- Yount, Lisa. Black Scientists. New York: Facts on File, 1991.

External links

[edit]- Profile of Ernest Just Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine - The Black Inventor Online Museum

- Works by or about Ernest Everett Just at the Internet Archive

- Ernest Everett Just at Find a Grave

- American cell biologists

- African-American biologists

- American marine biologists

- 1883 births

- 1941 deaths

- Omega Psi Phi founders

- Howard University faculty

- Dartmouth College alumni

- South Carolina State University alumni

- University of Chicago alumni

- Deaths from pancreatic cancer in Washington, D.C.

- 20th-century American zoologists

- 20th-century African-American scientists

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- People from Charleston, South Carolina

- Scientists from South Carolina