Mario Bros.

| Mario Bros. | |

|---|---|

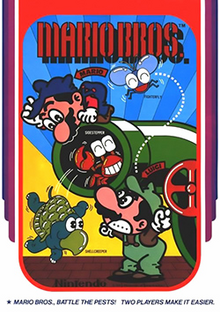

North American arcade flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo R&D1 (Arcade & NES) Intelligent Systems (NES & FDS)[2] Atari, Inc. (2600, 5200) MISA (PC-8001)[3] Choice Software (CPC, Spec) Ocean (C64) ITDC (7800) Sculptured Software (Atari 8-bit) |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Designer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto Gunpei Yokoi |

| Composer(s) | Yukio Kaneoka |

| Series | Mario |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | 1983

|

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Mario Bros.[a] is a 1983 platform game developed and published by Nintendo for arcades. It was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Gunpei Yokoi, Nintendo's chief engineer. Italian twin brother plumbers Mario and Luigi exterminate creatures, like turtles (Shellcreepers) and crabs emerging from the sewers by knocking them upside-down and kicking them away. The Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System version is the first game to be developed by Intelligent Systems. It is part of the Mario franchise, but originally began as a spin-off from the Donkey Kong series.

The arcade and Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System versions were received positively by critics. Elements introduced in Mario Bros., such as spinning bonus coins, turtles that can be flipped onto their backs, and Luigi, were carried over to Super Mario Bros. (1985) and became staples of the series.

An updated version, titled Mario Bros. Classic, is included as a minigame in all of the Super Mario Advance series and Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga (2003). The NES version of Mario Bros. had been re-released through the Wii and Wii U's Virtual Console as well as Nintendo Switch Online; the original arcade version was released by Hamster Corporation on the Nintendo Switch as part of the Arcade Archives series.[4]

Gameplay

[edit]

Mario Bros. features two plumbers,[5] Italian brothers Mario and Luigi, having to investigate the sewers after strange creatures have been appearing down there.[6] The objective of the game is to defeat all of the enemies in each phase. The mechanics of Mario Bros. involve only running and jumping.[7] Unlike future Mario games, players cannot jump on enemies and squash them, unless they were already turned on their back.[8] Each phase is a series of platforms with pipes at each corner of the screen, along with an object called a "POW" block in the center.[7] Phases use wraparound, meaning that enemies and players that go off to one side will reappear on the opposite side.[9] Points are scored for defeating enemies and collecting the bonus coins that emerge from the pipes afterward.[10]

Enemies are defeated by kicking them over once they have been flipped on their back.[11] This is accomplished by hitting the platform the enemy is on directly beneath them.[12] If the player allows too much time to pass after doing this the enemy will flip itself back over and recover.[11]

There are four enemies which emerge from the pipes: the Shellcreeper;[13] the Sidestepper;[7] the Fighter Fly,[12] which moves by jumping and can only be flipped when it is touching a platform; and the Slipice which turns platforms into slippery ice.[14] A fifth enemy, fireballs, floats around the screen instead of sticking to platforms.[15] The "POW" block will flip all enemies touching a platform or the floor when activated, but can only be used three times before disappearing.[14] The game additionally contains bonus rounds.[11] In later rounds, icicles begin to form on the underside of the platforms and fall off.

One life is lost whenever the player touches an un-flipped enemy, fireball, or fully formed icicle. The game ends when all lives are lost.

Development

[edit]

Mario Bros. was created by Shigeru Miyamoto and Gunpei Yokoi, two of the lead developers for the video game Donkey Kong. In Donkey Kong, Mario dies if he falls too far. For Mario Bros., Yokoi suggested to Miyamoto that Mario should be able to fall from any height, which Miyamoto was not sure of, thinking that it would make it "not much of a game". He eventually agreed, thinking it would be okay for him to have some superhuman abilities. He designed a prototype that had Mario "jumping and bouncing around", which he was satisfied with. The element of combating enemies from below was introduced after Yokoi suggested it, observing that it would work since there were multiple floors, but it proved to be too easy to eliminate enemies this way, which the developers fixed by requiring players to touch the enemies after they've been flipped to defeat them. This was also how they introduced the turtle as an enemy, which they conceived as an enemy that could only be hit from below.[16] Because of Mario's appearance in Donkey Kong with overalls, a hat, and a thick moustache, Miyamoto thought that he should be a plumber as opposed to a carpenter, and designed this game to reflect that.[17] Another contributing factor was the game's setting: it was a large network of giant pipes, so they felt a change in occupation was necessary for him.[6] The game's music was composed by Yukio Kaneoka.[18]

A popular story of how Mario went from Jumpman to Mario is that an Italian-American landlord, Mario Segale, had barged in on Nintendo of America (NOA)'s staff to demand rent, and they decided to name Jumpman after him.[19] This story is contradicted by former NOA warehouse manager Don James, who has stated that he and then-NOA president Minoru Arakawa named the character after Segale as a joke because Segale was so reclusive that none of the employees had ever met him.[20][21] Miyamoto also felt that the best setting for this game was New York because of its labyrinthine subterranean network of sewage pipes.[6] The pipes were inspired by several manga, which Miyamoto states feature waste grounds with pipes lying around. In this game, they were used in a way to allow the enemies to enter and exit the stage through them to avoid getting enemies piled up on the bottom of the stage. The green coloring of the pipes, which Nintendo late president Satoru Iwata called an uncommon color, came from Miyamoto having a limited color palette and wanting to keep things colorful. He added that green was the best because it worked well when two shades of it were combined.[16]

Mario Bros. introduced Mario's brother, Luigi, who was created for the multiplayer mode by doing a palette swap of Mario.[17] The two-player mode and several aspects of gameplay were inspired by Joust.[22] To date, Mario Bros. has been released for more than a dozen platforms.[23] The first movement from Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik is used at the start of the game.[24] This song has been used in later video games, including Dance Dance Revolution: Mario Mix[24] and Super Smash Bros. Brawl.[25]

Release

[edit]

The arcade game was released in 1983, but there are conflicting release dates. Game Machine magazine reported that the game made its North American debut at the AMOA show during March 25–27 and entered mass-production in Japan on June 21.[26] The book Arcade TV Game List (2006), authored by Masumi Akagi and published by the Amusement News Agency, lists the release dates as March 1983 in North America and June 1983 in Japan.[1] Former Nintendo president Satoru Iwata said in a 2013 Nintendo Direct presentation that the game was first released in Japan on July 6, 1983.[27][28]

Upon release, Mario Bros. was initially labeled as being the third game in the Donkey Kong series. For home video game conversions, Nintendo held the rights to the game in Japan, while licensing the overseas rights to Atari, Inc.[29]

Ports and other versions

[edit]Mario Bros. was ported by other companies to the Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari 8-bit computers, Atari 7800,[30] Amstrad CPC, and ZX Spectrum. The Commodore 64 has two versions: an Atarisoft port which was not commercially released[31] and a 1986 version by Ocean Software. The Atari 8-bit computer version by Sculptured Software is the only home port which includes the falling icicles. An Apple II version was never commercially released,[32] but copies of it appear to exist.[33]

A port by Nintendo and Intelligent Systems for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was released in North America in June 1986. Another NES port was released in August 1993 exclusively in Germany as part of the Classic Series.[34]

A port for NEC's PC-8001, unrelated to the Hudson Soft-developed Mario Bros. Special and Punch Ball Mario Bros., was developed by MISA and published by Westside Soft House in 1984.[35]

A modified version titled Kaettekita Mario Bros.,[b] was released only in Japan on November 30, 1988, for the Famicom Disk System through the Disk Writer service.[36]

In Taiwan and Mainland China, the game is sometimes nicknamed as Pipeline (管道) or Mr. Mary (瑪莉) due to the fact that pirated copies of this game were distributed widely, and pirate companies could not use the real name of the game and characters to bypass copyright.[citation needed]

The NES version of Mario Bros. was ported via the Virtual Console service in North America, Australia, Europe and Japan for the Wii,[37] Nintendo 3DS, and Wii U.[38][39] The original arcade version of Mario Bros. was released in September 2017 for the Nintendo Switch as part of the Arcade Archives series.[40] The NES version was a launch title for Nintendo Switch Online.[41]

Nintendo included Mario Bros. as a bonus in a number of releases, including Super Mario Bros. 3[42] and the Game Boy Advance's Super Mario Advance series[43] as well as Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga,[44] The NES version is included as a piece of furniture in Animal Crossing for the GameCube, along with many other NES games, though this one requires the use of a Nintendo e-Reader and a North America-exclusive Animal Crossing e-Card.[45]

In 2004, Namco released an arcade cabinet containing Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr. and Mario Bros. The latter was altered for the vertical screen used by the other games, with the visible play area cropped on the sides.[46]

Reception

[edit]| Publication | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atari 2600 | GBA | NES | Wii | |

| AllGame | ||||

| Computer and Video Games | 82%[12] | 83%[12] | ||

| GameSpot | 4.9/10[47] | |||

| IGN | 6/10 (e-Reader)[48] | 4.5/10[11] | ||

| Mean Machines | 80%[49] | |||

| Power Unlimited | 80%[51] | |||

Mario Bros. was initially a modest success in arcades,[52] with an estimated 2,000 arcade cabinets sold in the United States by July 1983.[53] It went on to be highly successful in American arcades.[54][55] In Japan, Game Machine listed Mario Bros. on their July 15, 1983, issue as being the third most-successful new table arcade unit of the month.[56] In the United States, Nintendo sold 3,800 Mario Bros. arcade cabinets.[57] The arcade cabinets have since become mildly rare and hard to find.[58] Despite being released during the video game crash of 1983, the arcade game was not affected. Video game author Dave Ellis considers it one of the more memorable classic games.[59] To date in Japan, the Famicom version of Mario Bros. has sold more than 1.63 million copies, and the Famicom Mini re-release has sold more than 90,000 copies.[60][61] The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) version went on to sell 2.28 million cartridges worldwide.[62] The Atari 2600 version also sold 1.59 million cartridges, making it one of the bestselling games of 1983.[63] This brings total Atari 2600, NES and Famicom Mini cartridge sales to 3.96 million units sold worldwide.

The NES and Atari versions of Mario Bros. received positive reviews from Computer and Video Games in 1989. They said the NES version is "incredibly good fun" especially in two-player mode, the Atari VCS version is "just as much fun" but with graphical restrictions, and the Atari 7800 version is slightly better.[12]

The 2009 Virtual Console re-release of the NES version later received mixed reviews, but received positive reviews from gamers.[11] In a review of the Virtual Console release, GameSpot criticized the NES version for being a poor port of the arcade version and that retains all of the technical flaws found in this version.[47] IGN complimented the Virtual Console version's gameplay, even though it was critical of Nintendo's decision to release an "inferior" NES port on the Virtual Console.[11] IGN also agreed on the issue of the number of ports. They said that since most people have Mario Bros. on one of the Super Mario Advance games, this version is not worth 500 Wii Points.[11] The Nintendo e-Reader version of Mario Bros. was slightly more well received by IGN, who praised the gameplay, but criticized it for lack of multiplayer and for not being worth the purchase because of the Super Mario Advance versions.[48]

The Super Mario Advance releases and Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga all featured the same version of Mario Bros. (titled Mario Bros. Classic). The mode was first included in Super Mario Advance, and was praised for its simplicity and entertainment value.[64] IGN called this mode fun in its review of Super Mario World: Super Mario Advance 2, but complained that it would have been nice if the developers had come up with a new game to replace it.[65] Their review of Yoshi's Island: Super Mario Advance 3 criticizes it more so than in the review of Super Mario Advance 2 because Nintendo chose not to add multiplayer to any of the mini-games found in that game, sticking instead with an identical version of the Mario Bros. game found in previous versions.[66] GameSpot's review of Super Mario Advance 4: Super Mario Bros. 3 calls it a throwaway feature that could have simply been gutted.[43] Other reviewers were not as negative on the feature's use in later Super Mario Advance games. Despite its use being criticized in most Super Mario Advance games, a GameSpy review called the version found in Super Mario Advance 2 a blast to play in multi-player because it only requires at least two Game Boy Advances, one copy of the game, and a link cable.[67]

Legacy

[edit]Related games

[edit]

In 1984, Hudson Soft made two different games based on Mario Bros. Mario Bros. Special[c] is a reimagining with new phases and gameplay. Punch Ball Mario Bros.[d] includes a new gameplay mechanic: punching small balls to stun enemies.[68] Both games were released for the PC-6001mkII,[69] PC-8001mkII,[70] PC-8801, FM-7 and Sharp X1.[68]

A version of the game was announced alongside the Virtual Boy hardware itself at Nintendo Space World 1994. Footage demonstrated showed a faithful recreation of the game, albeit with the Virtual Boy's trademark graphical qualities of monochrome red and black graphics and a slight stereoscopic 3D effect. Its demonstration was generally poorly received by video game publications, which lamented the selection of a decade-old game to demonstrate the technology of the new Virtual Boy hardware. Mario Bros. VB, as demonstrated, was never released, but some gameplay concepts were utilized in Mario Clash (1995), a much more creative reimagining of the original Mario Bros.[71][72][73][74][75]

Super Mario 3D World for the Wii U contains a version of Mario Bros. starring Luigi: Luigi Bros. This version, based on the NES port and included as a part of the Year of Luigi celebrations, replaced Mario with Luigi in his modern color scheme; the second player's sprite retains the original Luigi colors.[76][77]

High score

[edit]On October 16, 2015, Steve Kleisath obtained the world record for the arcade version at 5,424,920 points verified by Twin Galaxies.[78]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sources for the release dates are conflicting. Sources list it as somewhere between March and July 1983.

Japanese titles

References

[edit]- ^ a b Akagi, Masumi (October 13, 2006). アーケードTVゲームリスト国内•海外編(1971–2005) [Arcade TV Game List: Domestic • Overseas Edition (1971–2005)] (in Japanese). Japan: Amusement News Agency. pp. 57, 128. ISBN 978-4990251215.

- ^ "Works | Games | INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS CO., LTD". www.intsys.co.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Video Games Densetsu". Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ Whitehead, Thomas (September 13, 2017). "Mario Bros. to Kick Off 'Arcade Archives' Range on Nintendo Switch". Nintendo Life. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "Mario Bros. at Nintendo – Wii – Virtual Console". Nintendo.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c Sheff, David (1999). Game Over Press Start to Continue. Cyberactive Media Group. p. 56. ISBN 0-9669617-0-6.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Jeff (August 4, 2011). "4- Mario's Early Years". Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-51763-5. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Schartmann, Andrew (May 21, 2015). "1-2 Mario Grows Up". Koji Kondo's Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-62892-855-6. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Altice, Nathan (September 8, 2017). I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-262-53454-3. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ Gach, Ethan (May 6, 2020). "Mario Bros. Masters Set New Arcade High Score While Stuck At Home". Kotaku Australia. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mario Bros. (Virtual Console) Review". IGN. December 8, 2006. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Complete Games Guide" (PDF). Computer and Video Games (Complete Guide to Consoles): 46–77. October 16, 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ Barton, Matt (May 8, 2019). "18". Vintage Games 2.0: An Insider Look at the Most Influential Games of All Time. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-000-00776-3.

- ^ a b Weiss, Brett (November 12, 2012). Classic Home Video Games, 1985-1988: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0141-0.

- ^ Lendino, Jamie (August 17, 2023). "9: Games M-P". Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Steel Gear Press. ISBN 978-1-957932-04-0. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Wii.com – Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros. Wii". Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ a b "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN. November 8, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Famicom 20th Anniversary Original Sound Tracks Vol. 1 (Media notes). Scitron Digital Contents Inc. 2004. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ Zraick, Karen (November 2, 2018). "Mario Segale, Developer Who Inspired Nintendo to Name Super Mario, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (February 17, 2012). "Game Life Podcast: When Jay Mohr Met Tomonobu Itagaki". Wired. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

And so we thought, 'This guy [Segale] is a recluse. No one's ever actually met him.' So we thought, 'Wouldn't it be a great joke if we named this character Mario?' And so we said, 'That's great,' and we sent a telex to Japan, and that's how Mario got his name.

Interview with Don James starts at 51:16. Quotation occurs at 52:00. - ^ "Nintendo Treehouse Live - E3 2018 - Arcade Archives Donkey Kong, Sky Skipper". YouTube. Nintendo Everything. June 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

Mr. Arakawa, who was the president, and myself looked at the character, and we had a landlord that happened to be named Mario as well, and we'd never met the guy, so we thought it'd be funny to name this main character Mario after our landlord in Southcenter. And that's actually how Mario got his name.

Quotation occurs at 2:25. - ^ Fox, Matt (2006). The Video Games Guide. Boxtree Ltd. pp. 261–262. ISBN 0-7522-2625-8.

- ^ Eric Marcarelli. "Every Mario Game". Toad's Castle. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "Dance Dance Revolution: Mario Mix". NinDB. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Full Song List with Secret Songs – Smash Bros. DOJO!!". Nintendo. April 3, 2008. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 216. Amusement Press, Inc. July 15, 1983. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "Nintendo Direct 2.14.2013". Nintendo YouTube. YouTube. February 14, 2013. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Good, Owen (July 6, 2013). "Happy 30th Birthday to Video Gaming's Most Famous Brother". Kotaku. Gizmodo Media Group. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: Nintendo Licensed "Mario Brothers" To Atari Inc. For Home Video" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 218. Amusement Press, Inc. August 15, 1983. p. 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "Listing at GameSpot.com". Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Interview with Gregg Tavares". Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "Interview with Jimmy Huey". Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "Emulation of Apple IIgs port on Internet Archive".

- ^ "Mario Bros". GameFAQs. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ "「スペシャル」「パンチボール」じゃない元祖「マリオブラザーズ」が、パソコンに移植されていた!". akiba-pc.watch.impress.co.jp (in Japanese). June 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Lopes, Gonçalo (May 24, 2016). "Obscure Mario Bros. Famicom Disk System Game Gets Translated Into English". NintendoLife. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ "Mario Bros. (Virtual Console)". IGN. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ "Mario Bros. For Nintendo 3DS – Nintendo Game Details". Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "Mario Bros. For Wii U – Nintendo Game Details". Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ "Why does Mario Bros. cost $8 on the Nintendo Switch eShop?". Polygon. September 27, 2017. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Good, Owen S. (September 13, 2018). "Nintendo Switch Online has these 20 classic NES games". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Nintendo (1988). "pg. 27". Super Mario Bros. 3 manual (PDF). Nintendo Entertainment System. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Super Mario Advance 4: Super Mario Bros. 3 Review for Game Boy Advance". GameSpot. October 17, 2003. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga Guide – Mario Bros. Classic". IGN. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ^ "NES games". The Animal Forest. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Namco's new 3-in-1 retro cabinet featuring Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Mario Bros". Engadget. August 8, 2019. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Mario Bros. (NES)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 6, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

The NES version of Mario Bros. can be fun for a little while with two players, but it doesn't measure up to the seminal arcade hit it's based on.

- ^ a b "Mario Bros.-e Review". IGN. November 15, 2002. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Mean Machines". Computer and Video Games. No. 85 (November 1988). October 15, 1988. pp. 130–1.

- ^ Brett Alan Weiss. "Mario Bros. (NES) Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Power Unlimited Game Database". powerweb.nl (in Dutch). November 1994. Archived from the original on October 19, 2003. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN. November 8, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Fujihara, Mary (July 25, 1983). "Inter Office Memo: Coin-Op Product Sales" (PDF). Atari, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ McGill, Douglas C. (December 4, 1988). "Nintendo Scores Big". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ "News Bulletin: NBA Jam Sets Earnings Mark". Play Meter. Vol. 20, no. 1. January 1994. p. 3.

- ^ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25 – テーブル型新製品 (New Videos-Table Type)". Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 216. Amusement Press, Inc. July 15, 1983. p. 37.

- ^ Fujihara, Mary (November 2, 1983). "Inter Office Memo". Atari. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Ellis, David (2004). "Arcade Classics". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 391. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- ^ Ellis, David (2004). "A Brief History of Video Games". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 9. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- ^ "The Magic Box – Japan Platinum Chart Games". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendojofr". Nintendojo. September 26, 2006. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ CESA Games White Papers. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association.

- ^ Welch, Hanuman (April 23, 2013). "1984: Duck Hunt – The Best Selling Video Game Of Every Year Since 1977". Complex. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "Super Mario Advance Review for Game Boy Color – Gaming Age". Gaming Age. June 13, 2001. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Super Mario Advance 2: Super Mario World Review". IGN. February 11, 2002. Archived from the original on September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Super Mario Advance 3: Yoshi's Island". IGN. September 24, 2002. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Reviews: Super Mario World: Super Mario Advance 2 (GBA)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ a b "Virtually Overlooked: Punch Ball Mario Bros./Mario Bros. Special". GameDaily. September 11, 2008. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Szczepaniak, John (August 2010). "Hudson's Lost Mario Trilogy". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ Hubbard, Dustin+date=13 June 2021. "Mario Bros. Special (NEC PC-8001) Tape Dump and Scans". Gaming Alexandria. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rafferty, Kevin (November 16, 1994). "Super Mario takes leap into three dimensional space". The Guardian. ProQuest 294877556.

- ^ Electronic Gaming Monthly, January 1995, page 6

- ^ Edge, February 1995, pages 10-11

- ^ Electronic Gaming Monthly, January 1995, page 89

- ^ "Mario Clash". IGN. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Luigi Bros. unlockable, Rosalina playable in Super Mario 3D World". Polygon. November 13, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Buffa, Christopher (November 27, 2013). "Super Mario 3D World: How to Unlock Luigi Bros". Prima Games. Random House. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Mario Bros". Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Japanese)

- Official Nintendo Famicom Mini minisite (in Japanese)

- Official Nintendo Wii Virtual Console minisite (in Japanese)

- Official Nintendo 3DS eshop minisite (in Japanese)

- Official Nintendo Wii U eshop minisite (in Japanese)

- Official Nintendo Wii minisite (in English)

- Official Nintendo 3DS minisite (in English)

- Official Nintendo Wii minisite (in English)

- Mario Bros. on the Famicom 40th Anniversary page (in Japanese)

- Mario Bros. can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive (ZX Spectrum version)

- Mario Bros. at the Killer List of Videogames

- 1983 video games

- Amstrad CPC games

- Arcade Archives games

- Arcade video games

- Atari 2600 games

- Atari 5200 games

- Atari 7800 games

- Atari 8-bit computer games

- Atari games

- Commodore 64 games

- Cooperative video games

- Famicom Disk System games

- FM-7 games

- Game Boy Advance games

- Hudson Soft games

- Intelligent Systems games

- Mario video games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- NEC PC-8001 games

- NEC PC-8801 games

- Nintendo arcade games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Nintendo e-Reader games

- Nintendo Research & Development 1 games

- Nintendo Switch Online games

- Platformers

- PlayChoice-10 games

- Sculptured Software games

- Sharp X1 games

- Video games developed in Japan

- Video games directed by Shigeru Miyamoto

- Video games produced by Shigeru Miyamoto

- Video games scored by Fred Gray

- Video games set in New York City

- Virtual Console games

- Virtual Console games for Wii U

- ZX Spectrum games

- Hamster Corporation games