Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin | |

|---|---|

Rafał Lemkin | |

| |

| Born | 24 June 1900 Bezwodne, Volkovyssky Uyezd, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire (now Zelʹva District, Grodno Region, Belarus) |

| Died | 28 August 1959 (aged 59) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Education | University of Lwów |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for |

|

Raphael Lemkin (Polish: Rafał Lemkin; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish Jewish lawyer who is known for coining the term genocide and campaigning to establish the Genocide Convention. During the Second World War, he campaigned vigorously to raise international awareness of atrocities in Axis-occupied Europe. It was during this time that Lemkin coined the term "genocide" to describe Nazi Germany's extermination policies.[1]

As a young law student deeply conscious of antisemitic persecution, Lemkin learned about the Ottoman empire's genocide of Armenians during World War I and was deeply disturbed by the absence of international provisions to charge Ottoman officials who carried out war crimes.[2] Following the German invasion of Poland, Lemkin fled Europe and sought asylum in the United States, where he became an academic at Duke University.[2]

Lemkin coined genocide in 1943 or 1944 from two words: genos (Ancient Greek: γένος, 'family, clan, tribe, race, stock, kin')[3] and -cide (Latin: -cidium, 'killing').[4][5][6] The term was included in the 1944 research-work "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe", wherein Lemkin documented mass-killings of ethnic groups deemed "untermenschen" by Nazi Germany.[7] The concept of "genocide" was defined by Lemkin to refer to the various extermination campaigns launched by Nazi Germany to wipe out entire racial groups, including European Jews in the Holocaust.[8][9]

After the Second World War, Lemkin worked on the legal team of Robert H. Jackson, Chief US prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal. The concept of "genocide" was non-existent in any international laws at the time, and this became one of the reasons for Lemkin's view that the trial did not serve complete justice on prosecuting Nazi atrocities targeting ethnic and religious groups. Lemkin committed the rest of his life to push for an international convention, which in his view, was essential to prevent the rise of "future Hitlers". On 9 December 1948, the United Nations approved the Genocide Convention, with many of its clauses based on Lemkin's proposals.[10][11]

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Lemkin was born Rafał Lemkin on 24 June 1900 in Bezwodne, a village in the Volkovyssky Uyezd of the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus).[12][13][Note 1] He grew up in a Polish Jewish family on a large farm near Wolkowysk and was one of three children born to Józef Lemkin and Bella née Pomeranz.[12][14] His father was a farmer and his mother an intellectual, painter, linguist, and philosophy student with a large collection of books on literature and history.[15] Lemkin and his two brothers (Eliasz and Samuel) were homeschooled by their mother.[12]

As a youth, Lemkin was fascinated by the subject of atrocities and would often question his mother about such events as the Sack of Carthage, Mongol invasions and conquests and the persecution of Huguenots.[14][16] Lemkin apparently came across the concept of mass atrocities while, at the age of 12, reading Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz, in particular the passage where Nero threw Christians to the lions.[16] About these stories, Lemkin wrote, "a line of blood led from the Roman arena through the gallows of France to the Białystok pogrom." In his writings, Lemkin demonstrated a belief central to his thinking throughout his life: the suffering of Jews in eastern Poland was part of a larger pattern of injustice and violence that stretched back through history and around the world.[17]

The Lemkin family farm was located in an area in which fighting between Russian and German troops occurred during World War I.[18] The family buried their books and valuables before taking shelter in a nearby forest.[18] During the fighting, artillery fire destroyed their home and German troops seized their crops, horses and livestock.[18] Lemkin's brother Samuel eventually died of pneumonia and malnutrition while the family remained in the forest.[18]

After graduating from a local trade school in Białystok Lemkin began the study of linguistics at the Jan Kazimierz University of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine). He was a polyglot, fluent in nine languages and reading fourteen.[19] His first published book was a 1926 translation of the Hayim Nahman Bialik Hebrew novella "Behind the Fence"[20] into Polish, with the title Noah and Marinka.[21][22] It was in Białystok that Lemkin became interested in laws against mass atrocities after learning about the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire,[23][24][25][26][27][failed verification] then later the experience of Assyrians[28] massacred in Iraq during the 1933 Simele massacre.[29] He became interested in war crimes upon learning about the 1921 trial of Soghomon Tehlirian for the assassination of Talaat Pasha.[30]

After reading about the 1921 assassination of Talat Pasha, the main perpetrator of the Armenian genocide, in Berlin by Soghomon Tehlirian, Lemkin asked Professor Juliusz Makarewicz why Talat Pasha could not have been tried for his crimes in a German court. Makarewicz, a national-conservative who believed that Jews and Ukrainians should be expelled from Poland if they refused to assimilate, answered that the doctrine of state sovereignty gave governments the right to conduct internal affairs as they saw fit: "Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens. He kills them, and this is his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing." Lemkin replied, "But the Armenians are not chickens". His eventual conclusion was that "Sovereignty, I argued, cannot be conceived as the right to kill millions of innocent people".[31][32]

Lemkin then moved on to Heidelberg University in Germany to study philosophy, returning to Lwów to study law in 1926.[citation needed]

During the 1920s Lemkin was involved in Zionist activities. He was a columnist in the Warsaw based Yiddish Zionist newspaper Tsienistishe velt (The Zionist world).[33][34] Some scholars think that his Zionism had an influence on his conception of the idea of genocide, but there is a debate about the nature of this influence.[33][35][36][37]

Career in inter-war Poland

[edit]

Lemkin worked as an Assistant Prosecutor in the District Court of Brzeżany (since 1945 Berezhany, Ukraine) and Warsaw, followed by a private legal practice in Warsaw.[38] From 1929 to 1934, Lemkin was the Public Prosecutor for the district court of Warsaw. In 1930 he was promoted to Deputy Prosecutor in a local court in Brzeżany. While Public Prosecutor, Lemkin was also secretary of the Committee on Codification of the Laws of the Republic of Poland, which codified the penal codes of Poland. During this period Lemkin also taught law at the religious-Zionist Tachkemoni College in Warsaw,[33][34] and took part in Zionist fund raising.[33] Lemkin, working with Duke University law professor Malcolm McDermott, translated The Polish Penal Code of 1932 from Polish to English.[citation needed]

In 1933 Lemkin made a presentation to the Legal Council of the League of Nations conference on international criminal law in Madrid, for which he prepared an essay on the Crime of Barbarity as a crime against international law. In 1934 Lemkin, under pressure from the Polish Foreign Minister for comments made at the Madrid conference, resigned his position and became a private solicitor in Warsaw. While in Warsaw, Lemkin attended numerous lectures organized by the Free Polish University, including the classes of Emil Stanisław Rappaport and Wacław Makowski.[citation needed]

In 1937, Lemkin was appointed a member of the Polish mission to the 4th Congress on Criminal Law in Paris, where he also introduced the possibility of defending peace through criminal law. Among the most important of his works of that period are a compendium of Polish criminal fiscal law, Prawo karne skarbowe (1938) and a French-language work, La réglementation des paiements internationaux, regarding international trade law (1939).[citation needed]

During World War II

[edit]He left Warsaw on 6 September 1939 and made his way north-east towards Wolkowysk. He was caught between the invaders, the Germans in the west, and the Soviets who then approached from the east. Poland's independence was extinguished by terms of the pact between Stalin and Hitler.[39] He barely evaded German capture, and traveled through Lithuania to reach Sweden by early spring of 1940.[40] There he lectured at the University of Stockholm. Curious about the manner of imposition of Nazi rule he started to gather Nazi decrees and ordinances, believing official documents often reflected underlying objectives without stating them explicitly. He spent much time in the central library of Stockholm, gathering, translating and analysing the documents he collected, looking for patterns of German behaviour. Lemkin's work led him to see the wholesale destruction of the nations over which Germans took control as an overall aim. Some documents Lemkin analysed had been signed by Hitler, implementing ideas of Mein Kampf on Lebensraum, new living space to be inhabited by Germans.[41] With the help of his pre-war associate McDermott, Lemkin received permission to enter[42] the United States, arriving in 1941.[40]

Although he managed to save his own life, he lost 49 relatives in the Holocaust;[40] The only members of Lemkin's family in Europe who survived the Holocaust were his brother, Elias, and his brother's wife and two sons, who had been sent to a Soviet forced labor camp. Lemkin did however successfully help his brother and family to emigrate to Montreal, Quebec, Canada in 1948.[citation needed]

After arriving in the United States, at the invitation of McDermott, Lemkin joined the law faculty at Duke University in North Carolina in 1941.[43] During the Summer of 1942 Lemkin lectured at the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia. He also wrote Military Government in Europe, a preliminary version of what would become, in two years, his magnum opus, entitled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. In 1943 Lemkin was appointed consultant to the US Board of Economic Warfare and Foreign Economic Administration and later became a special adviser on foreign affairs to the War Department, largely due to his expertise in international law.[44]

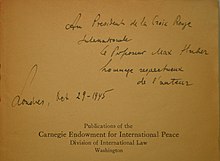

In November 1944, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. This book included an extensive legal analysis of German rule in countries occupied by Nazi Germany during the course of World War II, along with the definition of the term genocide.[45] Lemkin's idea of genocide as an offence against international law was widely accepted by the international community and was one of the legal bases of the Nuremberg Trials. In 1945 to 1946, Lemkin became an advisor to Supreme Court of the United States Justice and Nuremberg Trial chief counsel Robert H. Jackson. The book became one of the foundational texts in Holocaust studies, and the study of totalitarianism, mass violence, and genocide studies.[46]

Postwar

[edit]After the war, Lemkin chose to remain in the United States. Starting in 1948, he gave lectures on criminal law at Yale University. In 1955, he became a Professor of Law at Rutgers School of Law in Newark.[47] Lemkin also continued his campaign for international laws defining and forbidding genocide, which he had championed ever since the Madrid conference of 1933. He proposed a similar ban on crimes against humanity during the Paris Peace Conference of 1945, but his proposal was turned down.[48]

Lemkin presented a draft resolution for a Genocide Convention treaty to a number of countries, in an effort to persuade them to sponsor the resolution. With the support of the United States, the resolution was placed before the General Assembly for consideration. Among his supporters at the UN there were the delegates of Lebanon, and Lemkin is said to have considered Karim Azkoul in particular as an ally.[49] The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was formally presented and adopted on 9 December 1948.[50] In 1951, Lemkin only partially achieved his goal when the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide came into force, after the 20th nation had ratified the treaty.[51]

Lemkin's broader concerns over genocide, as set out in his Axis Rule,[52] also embraced what may be considered as non-physical, namely, psychological acts of genocide. The book also detailed the various techniques which had been employed to achieve genocide.[53]

Although Lemkin was a Zionist through his entire life,[33][35] during this period he downplayed his Zionist sympathies in order to convince the Arab and Muslim delegates in the UN to support the UN genocide convention.[33][54] Between 1953 and 1957, Lemkin worked directly with representatives of several governments, such as Egypt, to outlaw genocide under the domestic penal codes of these countries. Lemkin also worked with a team of lawyers from Arab delegations at the United Nations to build a case to prosecute French officials for genocide in Algeria.[55]

Lemkin also applied the term 'genocide' in his 1953 article "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine", which he presented as a speech in New York City.[56] Although the speech itself does not use the word "Holodomor", Lemkin asserts that an intentional program of starvation was the "third prong" of Soviet Russification of Ukraine, and disagrees that the deaths were simply a matter of disastrous economic policy because of the substantially Ukrainian ethnic profile of small farms in Ukraine at the time.[57][58][59]

Death and legacy

[edit]In the last years of his life, Lemkin was living in poverty in a New York apartment.[60] In 1959, at the age of 59, he died of a heart attack in New York City.[61] Only several close people attended his funeral at Riverside Church.[62] Lemkin was buried in Flushing, Queens, at Mount Hebron Cemetery.[63][64] At the time of his death, Lemkin left several unfinished works, including an Introduction to the Study of Genocide and an ambitious three-volume History of Genocide that contained seventy proposed chapters and a book-length analysis of Nazi war crimes at Nuremberg.[65]

The United States, Lemkin's adopted country, did not ratify the Genocide Convention during his lifetime. He believed that his efforts to prevent genocide had failed. "The fact is that the rain of my work fell on a fallow plain," he wrote, "only this rain was a mixture of the blood and tears of eight million innocent people throughout the world. Included also were the tears of my parents and my friends."[66] Lemkin was not widely known until the 1990s, when international prosecutions of genocide began in response to atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and "genocide" began to be understood as the worst crime of all crimes.[67]

Recognition

[edit]For his work on international law and the prevention of war crimes, Lemkin received a number of awards, including the Cuban Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos Manuel de Cespedes in 1950, the Stephen Wise Award of the American Jewish Congress in 1951, and the Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1955. On the 50th anniversary of the Convention entering into force, Lemkin was also honored by the UN Secretary-General as "an inspiring example of moral engagement." He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize ten times.[68]

In 1989 he was awarded, posthumously, the Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Worship.[69]

Lemkin is the subject of the plays Lemkin's House by Catherine Filloux (2005)[70] and If The Whole Body Dies: Raphael Lemkin and the Treaty Against Genocide by Robert Skloot (2006).[71] He was also profiled in the 2014 American documentary film, Watchers of the Sky.

Every year, The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights (T’ruah) gives the Raphael Lemkin Human Rights Award to a layperson who draws on his or her Jewish values to be a human rights leader.[72]

On 20 November 2015, Lemkin's article Soviet genocide in Ukraine was added to the Russian index of "extremist publications", whose distribution in Russia is forbidden.[73][74]

On 15 September 2018 the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation (www.ucclf.ca) and its supporters in the US unveiled the world's first Ukrainian/English/Hebrew/Yiddish plaque honouring Lemkin for his recognition of the tragic famine of 1932–1933 in the Soviet Union, the Holodomor, at the Ukrainian Institute of America, in New York City, marking the 75th anniversary of Lemkin's address, "Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine".

Works

[edit]- The Polish Penal Code of 1932 and The Law of Minor Offenses. Translated by McDermott, Malcolm; Lemkin, Raphael. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. 1939.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1933). Acts Constituting a General (Transnational) Danger Considered as Offences Against the Law of Nations (5th Conference for the Unification of Penal Law). Madrid.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lemkin, Raphael (1939). La réglementation des paiements internationaux; traité de droit comparé sur les devises, le clearing et les accords de paiements, les conflits des lois. Paris: A. Pedone.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1942). Key laws, decrees and regulations issued by the Axis in occupied Europe. Washington: Board of Economic Warfare, Blockade and Supply Branch, Reoccupation Division.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1943). Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, N.J: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Lemkin, Raphael (April 1945). "Genocide - A Modern Crime". Free World. 9 (4). New York: 39–43.

- Lemkin, Raphael (April 1946). "The Crime of Genocide". American Scholar. 15 (2): 227–30.

- "Genocide: A Commentary on the Convention". Yale Law Journal. 58 (7): 1142–56. June 1949. doi:10.2307/792930. JSTOR 792930.

See also

[edit]- Crimes against humanity

- War crime

- International criminal law

- Cultural genocide

- Gaza Genocide

- Rwandan Genocide

- Armenian genocide

- Holodomor

- The Holocaust

- Porajmos

- Hersch Lauterpacht

Notes

[edit]- ^ When Lemkin was born, the town was part of the Russian Empire. During the Interwar period it was located in Poland. In 1939, it was transferred to Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic and has been part of independent Belarus since 1991.

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention | Facing History & Ourselves". www.facinghistory.org. 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ γένος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Ishay 2008.

- ^ Jenkins 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Hyde, Jennifer (2 December 2008), Polish Jew gave his life defining, fighting genocide, CNN, retrieved 2 December 2008

- ^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

He moved to Washington, DC, in the summer of 1942, to join the War Department as an analyst and went on to document Nazi atrocities in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. In this text, he introduced the word "genocide."

- ^ "What is Genocide?". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

In 1944, Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term "genocide" in a book documenting Nazi policies of systematically destroying national and ethnic groups, including the mass murder of European Jews

- ^ "Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention | Facing History & Ourselves". www.facinghistory.org. 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023.

Lemkin himself had fled to the United States, where he struggled to draw attention to what Nazi Germany was doing to European Jews—massacres that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called "a crime without a name." In 1944, Lemkin made up a new word to describe these crimes: genocide. Lemkin defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or an ethnic group."

- ^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention | Facing History & Ourselves". www.facinghistory.org. 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Kornat 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Dan, Stone (2008). The Historiography of Genocide. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 10.

- ^ a b Power 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Szawłowski 2005, p. 102.

- ^ a b Schaller & Zimmerer 2009, p. 29.

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p.24

- ^ a b c d Power 2002, p. 21.

- ^ "NAPF Programs: Youth Outreach: Peace Heroes: Raphael Lemkin, by Holly A. Lukasiewicz". 10 February 2005. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Yudkin, Leon I. (2001). Bialik, Hayim Nahman; Patterson, David; Spicehandler, Ezra (eds.). "Bialik's Prose, and His Poetry Too". Hebrew Studies. 42: 299–313. ISSN 0146-4094. JSTOR 27913552.

- ^ Fogel, Joshua."Khayim-Nakhmen Byalik (Chaim Nachman, Hayim Nahman Bialik)". Yiddish Leksikon. Quote: "Noyekh un marinke (Noah and Marinka) (Warsaw, 1921)". Posted 7 January 2015, accessed 10 July 2022.

- ^ Sands, Phillipe (2016). East West Street. Penguin Randomhouse.

- ^ Yair Auron. The Banality of Denial: Israel and the Armenian Genocide. — Transaction Publishers, 2004. — p. 9:

...when Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1944 he cited the 1915 annihilation of Armenians as a seminal example of genocide"

- ^ William Schabas. Genocide in international law: the crimes of crimes. — Cambridge University Press, 2000. — p. 25:

Lemkin's interest in the subject dates to his days as a student at Lvov University, when he intently followed attempts to prosecute the perpetration of the massacres of the Armenians

- ^ A. Dirk Moses. Genocide and settler society: frontier violence and stolen indigenous children in Australian history. — Berghahn Books, 2004. — p. 21:"Indignant that the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide had largely escaped prosecution, Lemkin, who was a young state prosecutor in Poland, began lobbying in the early 1930s for international law to criminalize the destruction of such groups."

- ^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Lemkin's memoirs detail early exposure to the history of Ottoman attacks against Armenians (which most scholars believe constitute genocide), antisemitic pogroms, and other histories of group-targeted violence as key to forming his beliefs about the need for legal protection of groups.

- ^ "Genocide Background". Jewish World Watch. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

The Armenian genocide (1915–1923) was the first of the 20th century to capture world-wide attention; in fact, Raphael Lemkin coined his term genocide in reference to the mass murder of ethnic Armenians by the Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire.

- ^ Raphael Lemkin – EuropaWorld, 22 June 2001

- ^ Korey, William (June–July 1989). "Raphael Lemkin: 'The Unofficial Man'". Midstream. pp. 45–48.

- ^ "Operation Nemesis". NPR. 6 May 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2016). Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-8122-9341-8.

- ^ Ihrig, Stefan (2016). Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler. Harvard University Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-674-50479-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Loeffler, James (3 July 2017). "Becoming Cleopatra: the forgotten Zionism of Raphael Lemkin". Journal of Genocide Research. 19 (3): 340–360. doi:10.1080/14623528.2017.1349645. ISSN 1462-3528.

- ^ a b Madajczyk, Piotr (2023). The Biographical Landscapes of Raphael Lemkin. Taylor & Francis. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-000-99009-6.

- ^ a b Moses, A. Dirk (2021), "The Many Types of Destruction", The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression, Human Rights in History, Cambridge University Press, pp. 169–200, ISBN 978-1-107-10358-0

- ^ Moses, A. Dirk (2021). "Raphael Lemkin and the Protection of Small Nations". The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-107-10358-0.

- ^ Bartov, Omer; Moses, Direk; Loeffler, James (3 February 2022). "Discussion: Revision to Genocide". HaZman HaZe (This Time) (in Hebrew). Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p.69

- ^ Philippe Sands, East West Street, p. 159

- ^ a b c Paul R. Bartrop. Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO. 2014. pp. 1301–1302.

- ^ Sands, p.165

- ^ Sands, Philippe (27 May 2016). "69". East West Street: On the Origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity". New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-385-35071-6.

- ^ For more information on this period, see Bliwise, Robert. "The Man Who Criminalized Genocide". Duke Magazine. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Lemkin, Raphael (1944). "IX: Genocide—A New Term and New Conception for Destruction of Nations". Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation – Analysis of Government – Proposals for Redress. 700 Jackson Place, N. W. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Division of International Law. pp. 79–95. ISBN 9781584779018. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p.112

- ^ Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (October 2014). THE LIFE AND WORKS OF RAPHAEL LEMKIN: A POLITICAL HISTORY OF GENOCIDE IN THEORY AND LAW (Dissertation). Rutgers University. p. 363. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Eshet (2007).

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/book/5070/chapter-abstract/147627007. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Winter, Jay (2017). "Citation The Genesis Of Genocide". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. 29 (3). Vienna, Virginia: History.Net: 19.

- ^ "United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect". www.un.org.

- ^ Fussell, Jim. "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, Chapter IX: Genocide, by Raphael Lemkin, 1944 – – Prevent Genocide International". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Fussell, Jim. "Sec. II of Chap. IX from "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe," by Raphael Lemkin, 1944 – – Prevent Genocide International". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Cooper, J. (2008). Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-230-58273-6.

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p.217

- ^ Moses, A. Dirk (18 September 2012). Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). "Raphael Lemkin, Culture, and the Concept of Genocide". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232116.013.0002.

- ^ Raphael Lemkin, "Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine"

- ^ Antonovych, Myroslava (3 November 2015). "Legal Accountability for the Holodomor-Genocide of 1932–1933 (Great Famine) in Ukraine". Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal (1): 159–176. doi:10.18523/kmlpj52663.2015-1.159-176. ISSN 2414-9942.

- ^ Cooper, John (2008), "The United Nations Resolution on Genocide", Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 76–87, doi:10.1057/9780230582736_6, ISBN 978-1-349-35468-9, retrieved 22 October 2021

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p.1

- ^ "Raphael Lemkin Collection". Center for Jewish History.

- ^ "'In the Beginning, There Was No Word …'". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p. 229

- ^ Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (23 May 2017). Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812248647 – via Google Books.

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p. 216

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, pp. 1, 229

- ^ D. Irvin-Erickson, "Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide", University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, pp. 1, 2

- ^ "Nomination Database – Raphael Lemkin". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Four Freedoms Awards | Roosevelt Institute". Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Catherine Filloux – Playwright". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "If The Whole Body Dies: Raphael Lemkin and the Treaty Against Genocide by Robert Skloot". Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "awards | T'ruah". www.truah.org.

- ^ "Федеральный список экстремистских материалов дорос до п. 3152". SOVA Center for Information and Analysis. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "ФЕДЕРАЛЬНЫЙ СПИСОК ЭКСТРЕМИСТСКИХ МАТЕРИАЛОВ". The Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Eshet, Dan et al. (2007). Totally Unofficial: Rafael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention. Facing History and Ourselves Foundation, ISBN 978-0-9837870-2-0.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2017). Raphaël Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812248647.

- Ishay, Micheline R. (2008), The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalization Era, Berkeley (CA): University of California Press

- Jenkins, Bruce (2008). The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia—and How It Died. New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-147280-0.

- Kornat, Marek (2010), "Rafal Lemkin's Formative Years and the Beginning of International Career in Inter-war Poland (1918-1939)", in Zbiorowa, Praca (ed.), Rafał Lemkin: a Hero of Humankind, Polish Institute of International Affairs, ISBN 978-83-89607-85-0

- Power, Samantha (2002). A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-06150-8. (Chapters 2–5). Available at Open Library.

- Schaller, Dominik; Zimmerer, Jürgen (2009). The Origins of Genocide: Raphael Lemkin as a Historian of Mass Violence. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415480260.

- Szawłowski, Ryszard (2005). "Diplomatic File: Raphael Lemkin (1900–1959) – The Polish Lawyer Who Created the Concept of 'Genocide'". Polish Quarterly of International Affairs (2): 98–133.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Lemkin, Raphael, author; Frieze, Donna-Lee, editor (2013). Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin. Yale University Press, ISBN 0300186967.

- Beauvallet, Olivier (2011). Lemkin: face au génocide, with a French translation of "The legal case against Hitler" released in 1945. Paris: Éditions Michalon, "Le bien commun" series, ISBN 9782841865604.

- Bieńczyk-Missala, A. & Dębski, S., red. (2010). Rafał Lemkin: A Hero of Humankind. Warsaw: The Polish Institute of International Affairs.

- Bieńczyk-Missala, Agnieszka, scientific editor (2017). Civilians in contemporary armed conflicts: Rafał Lemkin's heritage (in English). Warsaw: University of Warsaw Publishing House

- Redzik, Adam & Zeman, Ihor. "Masters of Rafał Lemkin: Lwów school of law". pp. 235–240, ISBN 9788323527008.

- Redzik, Adam. "Rafał Lemkin (1900–1959) – co-creator of international criminal law. Short biography". p. 70, ISBN 978-83-931111-3-8.

- Cooper, John (2008). Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention. Palgrave/Macmallin. ISBN 0-230-51691-2.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2017). Raphaël Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812293418.

- Sands, Philippe (2016). East West Street: On the Origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity". New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-385-35071-6.

- Shaw, Martin (2007). What is Genocide? (Chapter 2). Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-3183-5.

Articles

[edit]- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- Totally Unofficial: Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention Archived 12 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine A study guide on Lemkin and his contributions to human rights law and activism, downloadable pdf at facinghistory.org

- Key writings of Raphael Lemkin on Genocide, 1933–1947, at preventgenocide.org

- Acts Constituting a General (Transnational) Danger Considered as Offenses Against the Law of Nations (for definitions of "barbarity" and "vandalism"), at preventgenocide.org

- Lemkin Discusses Armenian Genocide In Newly-Found 1949 CBS Interview, in: armeniapedia.org

- Balakian, Peter (Spring 2013). "Raphael Lemkin, Cultural Destruction, and the Armenian Genocide". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 27 (1): 57–89. doi:10.1093/hgs/dct001. S2CID 145008882. - Published on 1 April 2013

- Bieńczyk-Missala, A. (2020). "Raphael Lemkin's Legacy in International Law", in: M. Odello, P. Łubiński, The Concept of Genocide in International Criminal Law. Developments After Lemkin. Routledge.

- Browning, Christopher R. (24 November 2016). "The Two Different Ways of Looking at Nazi Murder" (review of Philippe Sands, East West Street: On the Origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity", Knopf.

- Elder, Tanya (December 2005). "What you see before your eyes: Documenting Raphael Lemkin's life by exploring his archival Papers,1900–1959" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. 7 (4): 469–499. doi:10.1080/14623520500349910. S2CID 56537572. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Elder, Tanya. Guide to the Papers of Raphael Lemkin. The Center for Jewish History, New York

- Gerlach, Christian (24 November 2016). The Extermination of the European Jews, Cambridge University Press, The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIII, no. 18, pp. 56–58. Discusses Hersch Lauterpacht's legal concept of "crimes against humanity", contrasted with Rafael Lemkin's legal concept of "genocide". All genocides are crimes against humanity, but not all crimes against humanity are genocides; genocides require a higher standard of proof, as they entail intent to destroy a particular group.

- Hartwell, L. (2021). " Raphael Lemkin: The Constant Negotiator". Negotiation Journal.

- Jacobs, Stephen Leonard (2019). "The Complicated Cases of Soghomon Tehlirian and Sholem Schwartzbard and Their Influences on Raphaël Lemkin's Thinking About Genocide". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 13 (1): 33–41. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.13.1.1594. Also here.

- Marrus, Michael R. (20 November 2015). "Three Roads from Nuremberg". Tablet magazine.

- Szawłowski, Ryszard (2015). Rafał Lemkin, warszawski adwokat (1934–1939), twórca pojęcia "genocyd" i główny architekt konwencji z 9 grudnia 1948 r. ("Konwencji Lemkina"). W 55-lecie śmierci (in Polish). [Rafał Lemkin, lawyer from Warsaw (1934–1939), creator of the term "genocide" and chief architect of the convention of December 9, 1948 (the "Lemkin Convention"). On the 55th anniversary of his death.]. Warsaw.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (December 2005). "Hostage of politics: Raphael Lemkin on "Soviet genocide"". Journal of Genocide Research. 7 (4): 551–559. doi:10.1080/14623520500350017. S2CID 144612446.

- Winter, Jay (7 June 2013). "Prophet Without Honors". The Chronicle Review: B14. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

External links

[edit]- Fogel, Joshua. "Rifoel (Raphael) Lemkin". Yiddish Leksikon. Biography with main publications including journalistic contributions. Posted 15 June 2017, accessed 10 July 2022.

- Raphael Lemkin papers, 1931–1947, held by Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library

- Raphael Lemkin papers, 1947–1959, held by the Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library

- Raphael Lemkin Collection, P-154 held by the American Jewish Historical Society, New York NY

- Raphael Lemkin Center for Genocide Prevention at the Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation

- Raphael Lemkin and the Quest to End Genocide Electronic exhibit by the Center for Jewish History at the Google Cultural Institute

- 20th-century Polish lawyers

- Polish legal scholars

- Jewish legal scholars

- International criminal law scholars

- Philosophers of law

- Rutgers School of Law–Newark faculty

- Duke University School of Law faculty

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Genocide prevention

- Armenian genocide and the Holocaust

- Recipients of the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Jewish anti-communists

- Polish anti-communists

- Polish emigrants to the United States

- Polish Zionists

- Polish Jews

- 20th-century Belarusian Jews

- People from Zelva District

- People from Volkovyssky Uyezd

- Jews from the Russian Empire

- Burials at Mount Hebron Cemetery (New York City)

- 1900 births

- 1959 deaths