Staveley, Derbyshire

| Staveley | |

|---|---|

Staveley Miners' Welfare | |

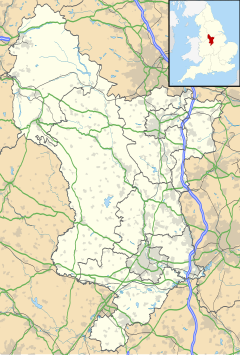

Location within Derbyshire | |

| Population | 18,247 (including Barrow Hill, Beighton Fields, Mastin Moor and Poolsbrook, civil parish, 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SK434749 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHESTERFIELD |

| Postcode district | S43 |

| Dialling code | 01246 |

| Police | Derbyshire |

| Fire | Derbyshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Staveley is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England. Located along the banks of the River Rother. It is (5 miles) northeast of Chesterfield, (5 miles) west of Clowne, (5 miles) northwest of Bolsover, (11 miles) southwest of Worksop and (13 miles) southeast of Sheffield.

History

[edit]

Staveley was formerly a mining town with several large coal mines in and around the area, the closest being Ireland Pit (Ireland Colliery Brass Band is named after the colliery). However, the pit has closed, along with the others in the area.

Staveley Miners Welfare on Market Street was built in 1893 as an indoor market hall by Charles Paxton Markham, for a time owner of Markham & Co. At that time, it was called Markham Hall in memory of his father.[2] Markham played a large role in the industrial development of the area around Staveley. Through his company Markham & Co. and its successor Staveley Coal and Iron Company, Markham owned ironstone quarries, several coal mines (including Markham Colliery), chemical works, ironworks and an engineering works specialising in mining and tunnelling equipment.

Other major local industries in recent history have included Staveley Works foundry and Staveley Chemicals. The nationwide decline in industry has meant that Staveley Chemicals and Staveley Works have now almost entirely closed, with the only section of the chemical plant remaining being the P-aminophenol plant (a key component to making Paracetamol), which is run by American/Irish company Covidien. Notice has been served on the plant, earmarked for closure around June 2012, this closure will mark the end of over 100 yrs. of chemical production at Staveley.[citation needed].

It is also the home town of the Townes Brewery.[3] Modern industry includes a plastic pipe moulding factory for Brett Martin plc. There was also a wood wool production unit on Staveley works.

The New Markham Vale Loop Road has been completed and opens up the former Markham coal field areas to development, linking the town to a new junction (29A) on the M1 motorway, this junction opened in early July 2008. This is part funded by European Union regeneration money. The scheme also reinstates part of the former Chesterfield Canal which crosses the route. There is a long-term project to reinstate the canal from Chesterfield to Kiveton where it currently terminates. Sections from Chesterfield to Brimington were reinstated as part of previous stages of the Chesterfield Bypass and opencast schemes on part of the former Staveley Coal and Iron Company site which was part of British Steel Corporation following Nationalisation. The new Staveley Town Basin was officially opened on 30 June 2012 and forms the centre piece of the imaginative redevelopment of the Chesterfield Canal in Staveley. The basin is designed to provide facilities to enable the economic development of the isolated section in advance of full restoration. It will provide secure short- and long-term moorings, slipway, car parking, cycle racks, toilets and showers as well as a large open play area which can also be used for major waterway events and festivals.[4]

As part of the Markham Vale scheme to regenerate the site of the former Markham Colliery site there was a proposal to build a "Solar Pyramid" to form the world's largest functional timepiece.[5] This project has now been cancelled. However, on the site near Poolsbrook Country Park, a caravan site for tourists has now been built boosting numbers to the country park. The area has several trails for walkers and mountain bikers along former pit railway lines.

Staveley Hall

[edit]

Staveley Hall is situated to the northeast of St John The Baptist Church in Staveley, with vehicular access from the Lowgates traffic island. The Hall in its present form was built in 1604 by Sir Peter Frecheville (c.1571-1634), MP. Before the current building there had been buildings on this site for over 700 years. A brief history of the building and its ownership follows:

- Hascuit de Musard was awarded the Manor of Staveley after the Norman Conquest of 1066.

- In 1306 the Musard family died out and Ralph de Frecheville became the new Lord.

- The Frechevilles lived in the Hall until they died out in 1682. In 1603 Sir Peter de Frecheville was knighted by James I at Worksop and he wished to make Staveley Hall a suitable residence for a knight and Justice of the Peace.

- The architect of Sir Peter de Frecheville's house is not known but may well be Huntingdon Smithson – the architect employed by the Cavendishes at Bolsover Castle.

- In 1682 and the house was sold to the Cavendish family. James Cavendish died in 1751 and the Hall and Park reverted to the Duke of Devonshire.

- In 1756 the Rector of Staveley managed to persuade the Duke of Devonshire to allow his son (and then a series of clerics) to live there.

- It remained as a rectory until bought by Staveley Urban District Council in 1967.

- The Hall was designated by English Heritage as a listed building (grade II) in 1974.

- Upon Local Government reorganisation in 1974 ownership passed to Chesterfield Borough Council and it was eventually bought by Staveley Town Council.[2][9][10][11][12]

Transport

[edit]Staveley was formerly served by four railway stations on two separate lines.

- Staveley Central was on the Great Central Main Line and Chesterfield Loop. It opened in 1892 as "Staveley Town" until being renamed as "Staveley Central" in 1950. It closed to passengers in 1964 and to freight in the 1980s. The platforms survived until the 2000s when a road, "Ireland Close", was built through the site. Nothing remains of the station other than the bridge carrying the road over the former railway.[13]

- Staveley Works was on the former Great Central Main Line and was the next stop north after Staveley Central. The station served the former Staveley Works. It opened in 1892 and closed in 1963. The platforms still survive although the site is now undeveloped land.[14]

- Barrow Hill was on the Doe Lea branch line from Chesterfield to Mansfield Woodhouse and the Old Road line from Chesterfield to Rotherham. The station opened in 1841 as "Staveley", only to then be renamed as "Barrow Hill and Staveley Works" in 1900 and finally renamed as "Barrow Hill" in 1951. It closed to passengers in 1954 and to all traffic in 1981. The site was cleared after closure and the line between Rotherham and Chesterfield still runs through the site. The Doe Lea Branch closed in the 1990s and the track has since been lifted. There have been proposals to reopen the station to serve the town of Staveley and surrounding areas.[15][16][17]

- Staveley Town was on the former Doe Lea and Clowne branch lines which connected the town to nearby towns of Bolsover and Clowne. The station opened in 1888 as "Netherthorpe" with the opening of the Clowne Branch Line. The line to Mansfield Woodhouse was then opened in 1890 and the station was renamed "Netherthorpe for Staveley Town" in 1893. The station was then finally renamed "Staveley Town" in 1900. The Doe Lea Branch closed to passengers in 1930 and the station was served by services on the Clowne Branch only until 1952. The station was demolished and the line was still in use until the 1990s when the branch lines were closed to both Creswell and Bolsover and Mansfield Woodhouse (after 1974). The site is now an unmarked footpath and there have been proposals to reuse this section of the railway for a possible Chesterfield to Rotherham line.[18][19][20]

Proposed Bypass

[edit]A road bypass of Staveley and Brimington has been proposed since 1927.[21] When the A61 Rother Way (also known as the Chesterfield Bypass) was constructed in the 1980s, a short dual carriageway spur was constructed over the River Rother and the Canal, terminating at a large roundabout which has an access road to a supermarket and the single carriageway A619 continuing to Brimington. The dual carriageway was planned to continue, heading northwards through Wheeldon Mill Greyhound Stadium (since demolished) before crossing the Canal twice and following the course of the Rother through Staveley Works. There would have likely been a grade separated junction between Mill Green and Hall Lane to serve the town and the nearby village of Barrow Hill. Then the dual carriageway would have curved eastward and run north of Mastin Moor, connecting to Junction 30 of the M1 at Barlborough. The plans caused controversy as the crossing of the Canal would have divided it into five linear ponds, and a petition put a halt to the bypass plans, but not before digging of a cutting had commenced.[22]

In 2009, the A6192 Ireland Close was built, connecting a small roundabout on Hall Lane to several more roundabouts near Poolsbrook, then to Junction 29A.

As part of regeneration proposals for Staveley Works, there is a 'spine road' proposed to run from the superstore roundabout off Rother Way to Hall Lane. However it is planned to be low speed single carriageway with several roundabouts or signal controlled junctions, which may create even more congestion.[23]

In July 2019, the MP for North East Derbyshire, Lee Rowley, gained support for a proper Staveley Bypass from the government.[24]

Media

[edit]Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC Yorkshire and ITV Yorkshire. Television signals are received from the Emley Moor TV transmitter and the Chesterfield TV transmitter.[25]

Radio stations are BBC Radio Sheffield, Hits Radio South Yorkshire, Greatest Hits Radio Yorkshire and local radio stations that broadcast from Chesterfield: S41 Radio, Elastic FM, Chesterfield Radio and Spire Radio.

The Derbyshire Times is the weekly local newspaper that serves the town.

Notable people

[edit]- Robert Keyes, participant in the Gunpowder Plot for which he was executed, was born about 1565, son of the then Rector of Staveley.

- John Frescheville, 1st Baron Frescheville, who family seat was in Staveley was elected a member of parliament 1628–9 and 1661–9. He was a Deputy Lieutenant for the county in 1639–42 and 1660, a Justice of the Peace from 1660, and a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber in 1639–45.

- William Hallam, President of the Derbyshire Miners' Association served as the clerk to Staveley Parish Council.

- Francis Rodes, judge, was born here and built the nearby Barlborough Hall as well as helping to found Netherthorpe School.[26]

- Thomas Rawson Birks, Cambridge Professor was born here 1810.

- William Young, cricketer born here in 1861.

- Harry and Will Lilley, footballers who played for Sheffield United were born here in 1868 and 1885 respectively.

- Sam Raybould, Liverpool striker, born here 1875.

- Nicholas Richard Ainger, a member of parliament, was educated here, at Netherthorpe School. The school was established in 1572 by four local notable families; Frecheville, De Rodes and Sitwell, which today comprise the school houses, and Cavendish.

- Chris Spedding, rock and roll and jazz guitarist, born here 1944.

- W.M. Hodgkins, artist and activist.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Neighbourhood Statistics". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Staveley Town Centre Trail". Staveley Town Council. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Real Ales @ Townes Brewery". townesbrewery.com. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Richardson, Christine, Lower John (2010). Chesterfield Canal – A Richlow Guide. Richlow. ISBN 978-0-9552609-4-0

- ^ "UK | England | First glimpse of giant pyramid". BBC News. 15 October 2002.

- ^ "The plaque over the front door shows the date, 1604 , his status as a Knight of the Realm and the coats of arms of his parents, Peter Frecheville and Margaret Kaye"[1]

- ^ Lyson, Magna Britannia, Derbyshire, 1817, p.lx

- ^ Arms of Kay per: Newton, William, A Display of Heraldry, London, 1846, p.50 [2]; Guillim, John, A Display of Heraldry, 1724 (6th ed.), p.194, gives the arms of Sir John Kay of Woodsom, Yorkshire as Argent, two bendlets sable[3]. The arms are not, as might be expected, for Fleetwood (Party per pale nebuly azure and or, six martlets, 2, 2 and 2 counterchanged), for the first wife of the builder, Joyce Fleetwood, whom he married in 1604)

- ^ "Staveley Hall Listing". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Staveley Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). Chesterfield Borough Council. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). The Buildings of England – Derbyshire. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09591-0.

- ^ Craven, Maxwell; Stanley, Michael (1982). The Derbyshire Country House. Derbyshire Museum Service. ISBN 0-906753-01-5.

- ^ "Disused Stations: Staveley Central Station". disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Disused Stations: SB-Staveley Works Station". disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Step forward for plans to reopen Barrow Hill Line from Chesterfield to Sheffield, through North Derbyshire". www.thestar.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Plan to reopen Barrow Hill rail line enters next stage". www.derbyshiretimes.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Plan to bring back passenger trains for Derbyshire villages". DerbyshireLive. 25 April 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "These 'lost' stations on historic Chesterfield to Sheffield railway could reopen as campaign gathers momentum". www.derbyshiretimes.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Staveley Developments and Regeneration - Chesterfield". Destination Chesterfield. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Disused Stations: Staveley Town Station". www.disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Tackling congestion and improving roads". Lee Rowley. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Staveley Regeneration Route" (PDF). 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Norcliffe, Liam (25 July 2019). "North East Derbyshire MP gains support for Staveley bypass project". Derbyshire Times. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Chesterfield (Derbyshire, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Whites 1857 Directory of Derbyshire p. 770-780

External links

[edit]- Various related information but in particular documenting the 2006 Archaeological dig that took place in the grounds of Staveley Hall

- Official Town Guide to Staveley

- Spire and District Online – Community Website originated in Staveley and run for the local area

- Photographs of the Last Remaining parts of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company (Last used as a Pipe Foundry)