Augustus FitzGeorge

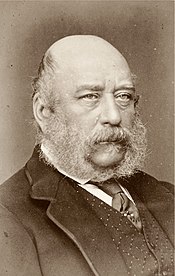

Sir Augustus FitzGeorge | |

|---|---|

Photograph of FitzGeorge (between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915) | |

| Birth name | Augustus Charles Frederick FitzGeorge |

| Born | 12 June 1847 London, UK |

| Died | 30 October 1933 (aged 86) 31 Queen's Gate, South Kensington, London, UK |

| Buried | Kensal Green Cemetery, London |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1864–1900 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 37th Regiment of Foot Rifle Brigade 11th Hussars |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath (1895) Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (1904) |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Relations | Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (father) Sarah Fairbrother (mother) George FitzGeorge (brother) Sir Adolphus FitzGeorge (brother) Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (grandfather) Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel (grandmother) King George III (great-grandfather) Queen Mary (first cousin) |

Colonel Sir Augustus Charles Frederick FitzGeorge, KCVO, CB (12 June 1847 – 30 October 1933) was a British Army officer and a relative of the British royal family. FitzGeorge was born in 1847 to Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, and his wife Sarah Fairbrother. His parents' marriage contravened the Royal Marriages Act 1772 and therefore invalid, thus FitzGeorge was ineligible to inherit the Dukedom of Cambridge.

FitzGeorge graduated from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in 1864, and served as an officer in the British Army until his retirement in 1900. He served as an aide-de-camp, accompanied Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) during his visit to India (1875–1876), and served as private secretary and equerry to his father, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces. In his later years, FitzGeorge served as the chairman of the Cobalt Townsite Silver Mining Company and the Casey Cobalt Mining Company, and as president of the National Health League.

Early life and family

[edit]FitzGeorge was born on 12 June 1847 at 31 Queen's Gate, South Kensington, London.[1][2][3] He was the third and youngest son of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, a member of the British royal family, by Sarah Fairbrother.[4][5][6] FitzGeorge's two older brothers were George FitzGeorge and Adolphus FitzGeorge.[2][4][6]

His parents had gone through a form of marriage several months before his birth, at St John Clerkenwell, London, on 8 January 1847. However Prince George had not sought and received Queen Victoria's consent to the marriage. Without the Queen's consent, the wedding ceremony was in contravention of the 1772 Royal Marriages Act, rendering the marriage void.[7] This meant the Duke's wife was not titled Duchess of Cambridge or accorded the style Her Royal Highness, while Augustus was, like his older brothers, illegitimate and ineligible to inherit the Dukedom of Cambridge from his father.[4] Through his father, FitzGeorge was a male-line grandson of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, and great-grandson of King George III.[5][8][9] As a descendant of George III, he was a first cousin once-removed of Queen Victoria and a first cousin of Queen Mary, who was the daughter of his paternal aunt, Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge.[3][5][10]

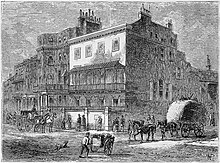

The three sons were raised by their mother at a house at 6 Queen Street in Mayfair, while their father lived nearby at his official residence, Gloucester House at Piccadilly and Park Lane.[3][11] FitzGeorge received his early education at private schools in England and Brussels.[3][12]

Military career

[edit]

FitzGeorge followed in his father's footsteps by serving in the British Army.[5] He attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and was gazetted in December 1864 as an ensign into the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot.[3][11] On 24 January 1865, FitzGeorge transferred from the 37th Regiment of Foot to become ensign in the Rifle Brigade.[3][13] While serving in the Rifle Brigade, he was stationed in Montreal with the 1st Battalion for five years, from 1865 to 1870.[3][5][14] On 14 July 1869, he was promoted to a lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade.[15]

In 1870, FitzGeorge was appointed aide-de-camp to General Robert Napier, 1st Baron Napier of Magdala, Commander-in-Chief of India and served in this position from 1870 until 1875.[3][5][11] While in India, he was part of the suite that accompanied Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) during his visit there from September 1875 until May 1876.[3][5][12]

FitzGeorge was promoted to captain in the Rifle Brigade in November 1877,[3] and on 20 March 1878, he transferred as a captain to the 11th Hussars, which were then stationed at Colchester Garrison.[3][11][16] He served with the 11th Hussars at Aldershot Garrison, Cavalry Barracks, Hounslow, and Birmingham.[3] While FitzGeorge was stationed at Aldershot, his regiment was ordered to embark for service at the Cape of Good Hope following the outbreak of the First Boer War.[3] However, this order was cancelled soon after, and he missed his first and only opportunity for active service.[3] In July 1881, FitzGeorge was promoted to major in the 11th Hussars.[17][18] He became extra aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Alison, 2nd Baronet, who was in command of troops at Aldershot Garrison on 1 December 1883.[3][18] FitzGeorge served Alison for two years.[3] In May 1886, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the 11th Hussars.[3][19] The Duke of Cambridge appointed FitzGeorge to serve as his equerry-in-waiting and private secretary on 11 August 1886.[3][19] In 1888, he attained the military rank of brevet colonel in the 11th Hussars.[3]

While his father continued to reside officially at Gloucester House,[20][21] his mother lived at nearby 6 Queen Street, which FitzGeorge inherited, along with all of its furniture, following her death in 1890.[3][22][23][24] By 1895, he had moved into Gloucester House to live with his father and manage his affairs.[20] When the Duke of Cambridge relinquished his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces on 1 November 1895, FitzGeorge was reverted to half-pay, as he was no longer private secretary to the commander-in-chief position.[25] However, he continued to serve as his father's private secretary and equerry.[26][27][28] FitzGeorge retired from the military on 1 November 1900.[2][3]

As equerry to the Duke of Cambridge, FitzGeorge accompanied his father as an attendant to significant British royal engagements, including: the funeral of his grandmother, Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, on 13 April 1889;[29] the wedding of his cousin Princess Mary of Teck and Prince George, Duke of York, at Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, on 6 July 1893;[30] the funeral of his aunt, Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, on 3 November 1897;[31] and the funeral and funeral procession for his uncle Francis, Duke of Teck, at St George's Chapel, Windsor, on 27 January 1900.[32]

His father served as the head of the British Army as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces from 1856 to 1895, spanning most of FitzGeorge's military career.[5] Regarding his career in the British Army, FitzGeorge remarked, "Throughout my life, I found my parentage rather a hindrance than a help."[5] He said that his father was so concerned with being accused of favouritism that when FitzGeorge was up for an appointment against another officer, the other officer received the appointment.[5] Following his many travels throughout his military career, FitzGeorge claimed to have hunted every type of big-game in the world.[12][33]

Later life

[edit]The Duke of Cambridge died on 17 March 1904, and FitzGeorge and his brother Adolphus travelled by carriage in his funeral procession.[34][35] Despite being the sons of the Duke of Cambridge, royal protocol relegated them to the ninth carriage in the procession, following the British royal family, official mourners, and foreign diplomats.[34][35]

Following their father's death, FitzGeorge and Adolphus became active in civic and charitable activities in London. FitzGeorge was appointed the same year Knight Commander in the Royal Victorian Order (K.C.V.O.).

In December 1904, they were involved with the development of a golf course on their father's Coombe estate in Kingston Hill.[36] The Crown had granted the estate to their father.[37] In 1911, FitzGeorge and his brother served on an honorary committee for the Ancient Art Exhibition at Earls Court in the summer of that year.[38] He and Adolphus also attended the dedication of an extension of the Wimbledon and Putney Commons in July 1911.[39] FitzGeorge and Adolphus continued a longstanding family tradition of distributing gifts of blankets and flannels to the employees of the former Duke of Cambridge's Coombe estate at Christmas.[40][41][42][43] When the FitzGeorge family's Coombe estate was sold in December 1932, it consisted of over 700 acres (280 ha) between Kingston Hill and New Malden, and included three golf courses: Coombe Hill, Coombe Wood, and Malden.[37]

FitzGeorge was also engaged in several business pursuits. He served as the executive chairman of the Cobalt Townsite Silver Mining Company of Canada, which had a silver mine in Cobalt, Ontario, during the Cobalt silver rush.[44] By the company's first annual meeting in December 1907, its mine had already shipped 117 tonnes (115 long tons; 129 short tons) of ore carrying 40,000 ounces (1,100,000 g) of silver.[44] He also served as the chairman for the Casey Cobalt Mining Company.[45]

In November 1913, the brothers were named as godparents (along with their cousin Queen Mary) to their great-nephew Victor FitzGeorge-Balfour, and attended his christening at Savoy Chapel.[46][47] FitzGeorge-Balfour was the son of FitzGeorge's niece, Mabel Iris FitzGeorge and her husband Robert Shekelton Balfour.[46][47]

On 1 February 1924, FitzGeorge sustained injuries in a vehicle accident in Kingston Hill while being driven in a taxicab.[48] The accident occurred after the driver became ill and lost control of the vehicle, causing it to turn over onto a sidewalk.[48] FitzGeorge was wounded by broken glass in the accident.[48]

By 1933, FitzGeorge served as the president of the National Health League, an organization that claimed a membership of approximately 2,000 British physicians.[49] The league was organised after ten years of planning, and in July 1933, it took issue publicly with the British Medical Association and with germ theory as the sole cause of disease.[49] The National Health League contended that environmental factors also played a role in illness, emphasised the importance of preventive healthcare and accused the British medical establishment of operating for profit.[49] At a meeting of health experts, FitzGeorge claimed that the British Army rejected 75 per cent of recruits for having preventable medical conditions.[49]

Death

[edit]FitzGeorge remained active into his later years and continued to play golf past the age of 80.[5][33] He resided at 6 Queen Street in Mayfair until near his death.[3] He died on 30 October 1933, at age 86, at a nursing home at 31 Queen's Gate in South Kensington, London.[3][50] He was the last surviving son of the Duke of Cambridge,[21][51] and the last surviving member of the suite that accompanied King Edward VII (then Prince of Wales) to India.[3][5] FitzGeorge never married.[3] At 86, he would have been one of the longest-living members of the British royal family, had he been recognized with the title and style of a male-line descendant of George III.

His funeral was held on 2 November 1933.[52][53] The first part of the funeral service was held at Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, with the permission of King George V.[52][53] King George and Queen Mary were represented by Edward Colebrooke, 1st Baron Colebrooke; Edward, Prince of Wales by his equerry Lieutenant Colonel Piers Legh; Prince Albert, Duke of York by Lieutenant Colonel Dermot McMorrough Kavanagh; and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Malcolm Donald Murray.[52][53][54] FitzGeorge was interred at Kensal Green Cemetery in Kensal Green, London.[52]

Honours

[edit]On 17 December 1895, Queen Victoria appointed FitzGeorge a Companion of the Order of the Bath.[26][28] On 28 March 1896, she sanctioned the publication of members of the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, in which FitzGeorge was named as an Esquire of the order.[26][55]

After King Edward VII assumed the British throne in 1901, the Duke of Cambridge requested that FitzGeorge and his brothers be given the rank of a British peer's younger sons.[21] King Edward did not honour this request;[21] however, he did confer the honour of Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order on FitzGeorge and his brother Adolphus the day after their father's funeral on 23 March 1904.[27][56][57]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Augustus FitzGeorge[58][59][60] |

|---|

References

[edit]- ^ Weir 1989, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Cokayne 1912, p. 499.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Colonel Sir Augustus FitzGeorge". The Times. London. 31 October 1933. p. 9. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c Stock 1904, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Sir Augustus FitzGeorge". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 31 October 1933. p. 10. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Cambridge 1906, p. 210.

- ^ Lyon, Ann (2016). Constitutional History of the UK. Taylor and Francis. p. 432. ISBN 978-1317203988.

- ^ Stock 1904, pp. 5–6.

- ^ St. Aubyn 1964, p. xiii.

- ^ St. Aubyn 1964, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ a b c d "Canadian Mine Owner Royally Descended". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. 5 September 1913. p. 5. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Sir A. FitzGeorge, Noted Soldier, Dead: British Colonel, a Big Game Hunter, Was Great-Grandson of King George III". The New York Times. New York. 31 October 1933. p. 21. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ "No. 22932". The London Gazette. 24 January 1865. p. 318.

- ^ "King's Cousin Here". The New York Times. New York. 4 September 1913. p. 20. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ "No. 23516". The London Gazette. 13 July 1869. p. 3957.

- ^ "No. 24564". The London Gazette. 19 March 1878. p. 2068.

- ^ "No. 24999". The London Gazette. 26 July 1881. p. 3678.

- ^ a b "No. 25322". The London Gazette. 26 February 1884. p. 968.

- ^ a b "No. 25616". The London Gazette. 13 August 1886. p. 3955.

- ^ a b St. Aubyn 1964, p. 325.

- ^ a b c d "A Great-Grandson of George III". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 31 October 1933. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cambridge 1906, p. 209.

- ^ "No. 34016". The London Gazette. 19 January 1934. p. 492.

- ^ "Probate of the will, dated Oct. 16th, 1889, of the late Mrs Sarah Farebrother". The Era. London. 5 April 1890. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Command-in-Chief of the Army". The Times. London. 2 November 1895. p. 5. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c Stock 1904, p. 7.

- ^ a b "No. 27661". The London Gazette. 25 March 1904. p. 1945.

- ^ a b "No. 10737". The Edinburgh Gazette. 20 December 1895. p. 1657.

- ^ "No. 25927". The London Gazette. 25 April 1889. p. 2333.

- ^ "No. 26424". The London Gazette. 18 July 1893. p. 4120.

- ^ "No. 26909". The London Gazette. 11 November 1897. p. 6225.

- ^ "Funeral of the Duke of Teck". The Times. London. 29 January 1900. p. 13. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b "Queen's Cousin Dead: Col. Sir Augustus Fitzgeorge Was 86 Years Old". Montreal Gazette. Montreal. 31 October 1933. p. 15. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Duff 1938, p. 283.

- ^ a b "The Late Duke of Cambridge". The Times. London. 22 March 1904. p. 8. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "New Course at Kingston-Hill". The Times. London. 19 December 1904. p. 12. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b "700 Acres Sold". The Times. London. 16 December 1932. p. 19. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "Ancient Art Exhibition". The Times. London. 21 January 1911. p. 9. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "Extension of Wimbledon Common". The Times. London. 26 July 1911. p. 13. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "Court News". The Times. London. 23 December 1911. p. 9. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. London. 23 December 1913. p. 11. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "The Christmas Holidays". The Times. London. 24 December 1910. p. 7. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. London. 21 December 1912. p. 9. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b Murray 1908, p. 700.

- ^ "Casey Cobalt Mining". The Standard. London. 18 January 1913. p. 4. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "The Queen as Godmother". The Times. London. 8 November 1913. p. 11. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b "Court Circular". The Times. London. 7 November 1913. p. 9. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c "Colonel Fitz George Injured. Cab Accident Due to Driver's Illness". The Times. London. 2 February 1924. p. 10. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c d "2000 British Doctors Ready for Medical Revolt". Vancouver Sun. Vancouver. 25 July 1933. p. 3. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cokayne 1998, p. 137.

- ^ "Sir Augustus FitzGeorge". The Times. London. 31 October 1933. p. 14. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c d "Funerals: Colonel Sir Augustus FitzGeorge". The Times. London. 3 November 1933. p. 17. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ a b c "The Late Sir Augustus FitzGeorge". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 3 November 1933. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. London. 3 November 1933. p. 17. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ "No. 26725". The London Gazette. 27 March 1896. p. 1959.

- ^ St. Aubyn 1964, pp. 350–351.

- ^ "The Late Duke of Cambridge". The Times. London. 26 March 1904. p. 14. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via The Times Archive.

- ^ Stock 1904, pp. 5–9.

- ^ Weir 1989, pp. 285–297.

- ^ Duff 1938, p. 284.

- ^ a b Camp 2007, pp. 330–338.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cambridge, George, Duke of (1906). Sheppard, Edgar (ed.). George Duke of Cambridge: A Memoir of his Private Life. Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. OCLC 604626 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Camp, Anthony J. (2007). Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction 1714–1936. London: Anthony J. Camp. ISBN 978-0-9503308-2-2. OCLC 260200087.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1912). Gibbs, Vicary (ed.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. Vol. II. London: St Catherine Press. OCLC 1114291328 – via Internet Archive.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1998). Hammond, Peter W. (ed.). The Complete Peerage, or a History of the House of Lords and All Its Members From the Earliest Times, Volume XIV: Addenda & Corrigenda. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 9780750901543. OCLC 695728820.

- Duff, Ethel M. Bailey (1938). The Life Story of H.R.H. The Duke of Cambridge. London: Stanley Paul. OCLC 71881864 – via Internet Archive.

- Murray, J. C., ed. (1908). "Cobalt Townsite Silver Mining Company of Canada, Limited". Canadian Mining Journal. 29. Toronto: Mines Publishing Company, Limited; Canadian Mining Institute: 700. OCLC 1041553997 – via Internet Archive.

- St. Aubyn, Giles (1964). The Royal George, 1819–1904: The Life of H.R.H. Prince George, Duke of Cambridge. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 4122129 – via Internet Archive.

- Stock, Elliot, ed. (May 1904). "The Genealogical Magazine: A Journal of Family Heraldry & Pedigrees". Vol. 7–8. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 173399016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2017 – via Google Books.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Weir, Alison (1989). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-370-31310-8. OCLC 1008227480.

External links

[edit] Media related to Augustus FitzGeorge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Augustus FitzGeorge at Wikimedia Commons- National Portrait Gallery: Sir Augustus Charles Frederick FitzGeorge

- 1847 births

- 1933 deaths

- 11th Hussars officers

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- 20th-century English businesspeople

- British mining businesspeople

- British nonprofit executives

- Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery

- Businesspeople from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

- Businesspeople from the City of Westminster

- Companions of the Order of the Bath

- Equerries

- Esquires of the Order of St John

- FitzGeorge family

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- Illegitimate children of British princes

- Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

- Military personnel from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

- People from Mayfair

- People from South Kensington

- Rifle Brigade officers

- Private secretaries

- British Army colonels

- Military personnel from the City of Westminster