Macedonian language

| Macedonian | |

|---|---|

| македонски makedonski | |

| Pronunciation | [maˈkɛdɔnski] |

| Native to | North Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Serbia |

| Region | Balkans |

| Ethnicity | Macedonians |

Native speakers | 1.6 million (2022)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Macedonian Language Institute "Krste Misirkov" at the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mk |

| ISO 639-2 | mac (B) mkd (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | mkd |

| Glottolog | mace1250 |

| Linguasphere | (part of 53-AAA-h) 53-AAA-ha (part of 53-AAA-h) |

The Macedonian-speaking world:[image reference needed] regions where Macedonian is the language of the majority regions where Macedonian is the language of a minority | |

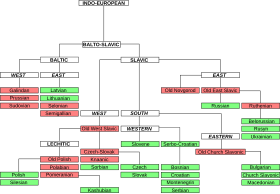

Macedonian (/ˌmæsɪˈdoʊniən/ MASS-ih-DOH-nee-ən; македонски јазик, translit. makedonski jazik, pronounced [maˈkɛdɔnski ˈjazik] ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around 1.6 million people, it serves as the official language of North Macedonia.[1] Most speakers can be found in the country and its diaspora, with a smaller number of speakers throughout the transnational region of Macedonia. Macedonian is also a recognized minority language in parts of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, and Serbia and it is spoken by expatriate communities predominantly in Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Macedonian developed out of the western dialects of the Eastern South Slavic dialect continuum, whose earliest recorded form is Old Church Slavonic. During much of its history, this dialect continuum was called "Bulgarian",[5][additional citation(s) needed] although in the late 19th century, its western dialects came to be known separately as "Macedonian".[citation needed] Standard Macedonian was codified in 1945 and has developed modern literature since.[6] As it is part of a dialect continuum with other South Slavic languages, Macedonian has a high degree of mutual intelligibility with Bulgarian and varieties of Serbo-Croatian.

Linguists distinguish 29 dialects of Macedonian, with linguistic differences separating Western and Eastern groups of dialects. Some features of Macedonian grammar are the use of a dynamic stress that falls on the ante-penultimate syllable, three suffixed deictic articles that indicate noun position in reference to the speaker and the use of simple and complex verb tenses. Macedonian orthography is phonemic with a correspondence of one grapheme per phoneme. It is written using an adapted 31-letter version of the Cyrillic script with six original letters. Macedonian syntax is the same as of all other modern Slavic languages, i.e. of the subject-verb-object (SVO) type and has flexible word order.[7][8]

Macedonian vocabulary has been historically influenced by Turkish and Russian. Somewhat less prominent vocabulary influences also came from neighboring and prestige languages. The international consensus outside of Bulgaria is that Macedonian is an autonomous language within the Eastern South Slavic dialect continuum, although since Macedonian and Bulgarian are mutually intelligible and are socio-historically related, a small minority of linguists are divided in their views of the two as separate languages or as a single pluricentric language.[9][10][11]

5 May, the day when the government of Yugoslav Macedonia adopted the Macedonian alphabet as the official script of the republic, is marked as Macedonian Language Day.[12] This is a working holiday, declared as such by the government of North Macedonia in 2019.[13]

Classification and related languages

Macedonian belongs to the eastern group of the South Slavic branch of Slavic languages in the Indo-European language family, together with Bulgarian and the extinct Old Church Slavonic. Some authors also classify the Torlakian dialects in this group. Macedonian's closest relative is Bulgarian followed by Serbo-Croatian and Slovene, although the last is more distantly related.[14][15] Together, South Slavic languages form a dialect continuum.[16][17]

Macedonian, like the other Eastern South Slavic idioms has characteristics that make it part of the Balkan sprachbund, a group of languages that share typological, grammatical and lexical features based on areal convergence, rather than genetic proximity.[18] In that sense, Macedonian has experienced convergent evolution with other languages that belong to this group such as Greek, Aromanian, Albanian and Romani due to cultural and linguistic exchanges that occurred primarily through oral communication.[18]

Macedonian and Bulgarian are divergent from the remaining South Slavic languages in that they do not use noun cases (except for the vocative, and apart from some traces of once productive inflections still found scattered throughout these two) and have lost the infinitive.[19] They are also the only Slavic languages with any definite articles (unlike standard Bulgarian, which uses only one article, standard Macedonian as well as some south-eastern Bulgarian dialects[20] have a set of three deictic articles: unspecified, proximal and distal definite article). Macedonian, Bulgarian and Albanian are the only Indo-European languages that make use of the narrative mood.[21]

According to Chambers and Trudgill, the question whether Bulgarian and Macedonian are distinct languages or dialects of a single language cannot be resolved on a purely linguistic basis, but should rather take into account sociolinguistic criteria, i.e., ethnic and linguistic identity.[22] This view is supported by Jouko Lindstedt, who has suggested the reflex of the back yer as a potential boundary if the application of purely linguistic criteria were possible.[23][24]

As for the Slavic dialects of Greece, Trudgill classifies the dialects in the east Greek Macedonia as part of the Bulgarian language area and the rest as Macedonian dialects.[25] According to Riki van Boeschoten,[26] dialects in eastern Greek Macedonia (around Serres and Drama) are closest to Bulgarian, those in western Greek Macedonia (around Florina and Kastoria) are closest to Macedonian, while those in the centre (Edessa and Salonica) are intermediate between the two.[27][28]

History

The Slavic people who settled in the Balkans during the 6th century CE, spoke their own dialects and used different dialects or languages to communicate with other people.[29] The "canonical" Old Church Slavonic period of the development of Macedonian started during the 9th century and lasted until the first half of the 11th century. It saw translation of Greek religious texts.[30][31][32] The Macedonian recension of Old Church Slavonic also appeared around that period in the Bulgarian Empire and was referred to as such due to works of the Ohrid Literary School.[33] Towards the end of the 13th century, the influence of Serbian increased as Serbia expanded its borders southward.[34] During the five centuries of Ottoman rule, from the 15th to the 20th century, the vernacular spoken in the territory of current-day North Macedonia witnessed grammatical and linguistic changes that came to characterize Macedonian as a member of the Balkan sprachbund.[35][36] This period saw the introduction of many Turkish loanwords into the language.[37]

The latter half of the 18th century saw the rise of modern literary Macedonian through the written use of Macedonian dialects referred to as "Bulgarian" by writers.[35] The first half of the 19th century saw the rise of nationalism among the South Slavic people in the Ottoman Empire.[38] This period saw proponents of creating a common church for Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs which would use a common modern Macedo-Bulgarian literary standard.[39][40]

The period between 1840 and 1870, saw a struggle to define the dialectal base of the common language called simply "Bulgarian", with two opposing views emerging.[37][39] One ideology was to create a Bulgarian literary language based on Macedonian dialects, but such proposals were rejected by the Bulgarian codifiers.[35][39] That period saw poetry written in the Struga dialect with elements from Russian.[41] Textbooks also used either spoken dialectal forms of the language or a mixed Macedo-Bulgarian language.[42] Subsequently, proponents of the idea of using a separate Macedonian language emerged.[43]

Krste Petkov Misirkov's book Za makedonckite raboti (On Macedonian Matters) published in 1903, was the first attempt to formalize a separate literary language.[44] With the book, the author proposed a Macedonian grammar and expressed the goal of codifying the language and using it in schools. The author postulated the principle that the Prilep-Bitola dialect be used as a dialectal basis for the formation of the Macedonian standard language; his idea however was not adopted until the 1940s.[35][41] On 2 August 1944 at the first Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) meeting, Macedonian was declared an official language.[35][45] With this, it became the last of the major Slavic languages to achieve a standard literary form.[32] As such, Macedonian served as one of the three official languages of Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1991.[46]

Geographical distribution

Although the precise number of native and second language speakers of Macedonian is unknown due to the policies of neighboring countries and emigration of the population, estimates ranging between 1.4 million and 3.5 million have been reported.[47][14] According to the 2002 census, the total population of North Macedonia was 2,022,547, with 1,344,815 citizens declaring Macedonian their native language.[48] Macedonian is also studied and spoken to various degrees as a second language by all ethnic minorities in the country.[14][49]

Outside North Macedonia, there are small ethnic Macedonian minorities that speak Macedonian in neighboring countries including 4.697 in Albania (1989 census),[50] 1,609 in Bulgaria (2011 census)[51] and 12,706 in Serbia (2011 census).[52] The exact number of speakers of Macedonian in Greece is difficult to ascertain due to the country's policies. Estimates of Slavophones ranging anywhere between 50,000 and 300,000 in the last decade of the 20th century have been reported.[53][54] Approximately 580,000 Macedonians live outside North Macedonia per 1964 estimates with Australia, Canada, and the United States being home to the largest emigrant communities. Consequently, the number of speakers of Macedonian in these countries include 66,020 (2016 census),[55] 15,605 (2016 census)[56] and 22,885 (2010 census), respectively.[57] Macedonian also has more than 50,000 native speakers in countries of Western Europe, predominantly in Germany, Switzerland and Italy.[58]

The Macedonian language has the status of an official language only in North Macedonia, and is a recognized minority and official language in parts of Albania (Pustec),[59][60] Romania, Serbia (Jabuka and Plandište)[4] and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2] There are provisions to learn Macedonian in Romania as Macedonians are an officially recognized minority group.[3] Macedonian is studied and taught at various universities across the world and research centers focusing on the language are found at universities across Europe (France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Russia) as well as Australia, Canada and the United States (Chicago and North Carolina).[61]

Dialects

During the standardization process of the Macedonian language, the dialectal base selected was primarily based on the West-Central dialects, which spans the triangle of the communities Makedonski Brod, Kičevo, Demir Hisar, Bitola, Prilep, and Veles. These were considered the most widespread and most likely to be adopted by speakers from other regions.[62] The initial idea to select this region as a base was first proposed in Krste Petkov Misirkov's works as he believed the Macedonian language should abstract on those dialects that are distinct from neighboring Slavic languages, such as Bulgarian and Serbian.[63]

| |

| Dialect divisions of Macedonian per Macedonian dialectology.[24][64] | |

Lower Polog / Tetovo Crna Gora Kumanovo / Kratovo (Torlakian dialects)

Central Drimkol / Golo Brdo Reka Debar Small Reka / Galičnik Upper Polog / Gostivar Vevčani / Radοžda Upper Prespa / Ohrid

|

Mariovo / Tikveš Štip / Strumica Maleševo / Pirin

Solun / Voden Ser / Drama

Lower Prespa Korča Kostur Nestram

|

Based on a large group of features, Macedonian dialects can be divided into Eastern, Western and Northern groups. The boundary between them geographically runs approximately from Skopje and Skopska Crna Gora along the rivers Vardar and Crna.[29] There are numerous isoglosses between these dialectal variations, with structural differences in phonetics, prosody (accentuation), morphology and syntax.[29] The Western group of dialects can be subdivided into smaller dialectal territories, the largest group of which includes the central dialects.[65] The linguistic territory where Macedonian dialects were spoken also span outside the country and within the region of Macedonia, including Pirin Macedonia into Bulgaria and Aegean Macedonia into Greece.[18]

Variations in consonant pronunciation occur between the two groups, with most Western regions losing the /x/ and the /v/ in intervocalic position (глава (head): /ɡlava/ = /ɡla/: глави (heads): /ɡlavi/ = /ɡlaj/) while Eastern dialects preserve it. Stress in the Western dialects is generally fixed and falls on the antepenultimate syllable while Eastern dialects have non-fixed stress systems that can fall on any syllable of the word,[66] that is also reminiscent of Bulgarian dialects. Additionally, Eastern dialects are distinguishable by their fast tonality, elision of sounds and the suffixes for definiteness. The Northern dialectal group is close to South Serbian and Torlakian dialects and is characterized by 46–47 phonetic and grammatical isoglosses.[67]

In addition, a more detailed classification can be based on the modern reflexes of the Proto-Slavic reduced vowels (yers), vocalic sonorants, and the back nasal *ǫ. That classification distinguishes between the following 6 groups:[68]

- Macedonian

- Western dialects

- Ohrid-Prespa Group: Ohrid dialect, Struga dialect, Vevčani-Radožda dialect, Upper Prespa dialect and Lower Prespa dialect.

- Debar Group: Debar dialect, Reka dialect, Drimkol-Golo Brdo dialect, Small Reka dialect (Galičnik dialect), Skopska Crna Gora dialect and Gora dialect

- Polog Group: Upper Polog dialect (Gostivar dialect), Lower Polog dialect (Tetovo dialect), Prilep-Bitola dialect, Kičevo-Poreče dialect and Skopje-Veles dialect

- Kostur-Korča Group: Korča dialect, Kostur dialect and Nestram-Kostenar dialect

- Eastern dialects

- Northern Group: Kumanovo dialect, Kratovo dialect, Kriva Palanka dialect and Ovče Pole dialect

- Eastern Group: Štip - Kočani dialect, Strumica dialect, Tikveš-Mariovo dialect, Maleševo-Pirin dialect, Solun-Voden dialect and Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect.

- Western dialects

Phonology

The phonological system of Standard Macedonian is based on the Prilep-Bitola dialect. Macedonian possesses five vowels, one semivowel, three liquid consonants, three nasal stops, three pairs of fricatives, two pairs of affricates, a non-paired voiceless fricative, nine pairs of voiced and unvoiced consonants and four pairs of stops. Out of all the Slavic languages, Macedonian has the most frequent occurrence of vowels relative to consonants with a typical Macedonian sentence having on average 1.18 consonants for every one vowel.[69]

Vowels

The Macedonian language contains 5 vowels which are /a/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /o/, and /u/. For the pronunciation of the middle vowels /е/ and /о/ by native Macedonian speakers, various vowel sounds can be produced ranging from [ɛ] to [ẹ] and from [o] to [ọ]. Unstressed vowels are not reduced, although they are pronounced more weakly and shortly than stressed ones, especially if they are found in a stressed syllable.[70][71] The five vowels and the letter р (/r/) which acts as a vowel when found between two consonants (e.g. црква, "church"), can be syllable-forming.[66]

The schwa is phonemic in many dialects (varying in closeness to [ʌ] or [ɨ]) but its use in the standard language is marginal.[72] When writing a dialectal word and keeping the schwa for aesthetic effect, an apostrophe is used; for example, ⟨к’смет⟩, ⟨с’нце⟩, etc. When spelling words letter-by-letters, each consonant is followed by the schwa sound. The individual letters of acronyms are pronounced with the schwa in the same way: ⟨МПЦ⟩ ([mə.pə.t͡sə]). The lexicalized acronyms ⟨СССР⟩ ([ɛs.ɛs.ɛs.ɛr]) and ⟨МТ⟩ ([ɛm.tɛ]) (a brand of cigarettes), are among the few exceptions. Vowel length is not phonemic. Vowels in stressed open syllables in disyllabic words with stress on the penultimate can be realized as long, e.g. ⟨Велес⟩ [ˈvɛːlɛs] 'Veles'. The sequence /aa/ is often realized phonetically as [aː]; e.g. ⟨саат⟩ /saat/ [saːt] 'colloq. hour', ⟨змии⟩ - snakes. In other words, two vowels appearing next to each other can also be pronounced twice separately (e.g. пооди - to walk).[66]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | ɛ | (ə) | ɔ |

| Open | a |

Consonants

The consonant inventory of the Macedonian language consists of 26 letters and distinguishes three groups of consonants (согласки): voiced (звучни), voiceless (безвучни) and sonorant consonants (сонорни).[71] Typical features and rules that apply to consonants in the Macedonian language include assimilation of voiced and voiceless consonants when next to each other, devoicing of vocal consonants when at the end of a word, double consonants and elision.[71][74] At morpheme boundaries (represented in spelling) and at the end of a word (not represented in spelling), voicing opposition is neutralized.[71]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n̪1 | ɲ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t̪ | c3 | k | |

| voiced | b | d̪ | ɟ3 | ɡ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | t̪͡s̪ | t͡ʃ | |||

| voiced | d̪͡z̪ | d͡ʒ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s̪ | ʃ | x2 | |

| voiced | v | z̪ | ʒ | |||

| Approximant | ɫ̪1 | l | j | |||

| Trill | r1 | |||||

^1 The alveolar trill (/r/) is syllabic between two consonants; for example, ⟨прст⟩ [ˈpr̩st] 'finger'. The dental nasal (/n/) and dental lateral (/ɫ/) are also syllabic in certain foreign words; e.g. ⟨њутн⟩ [ˈɲutn̩] 'newton', ⟨Попокатепетл⟩ [pɔpɔkaˈtɛpɛtɫ̩] 'Popocatépetl', etc. The labiodental nasal [ɱ] occurs as an allophone of /m/ before /f/ and /v/ (e.g. ⟨трамвај⟩ [ˈtraɱvaj] 'tram').[citation needed] The velar nasal [ŋ] similarly occurs as an allophone of /n/ before /k/ and /ɡ/ (e.g. ⟨англиски⟩ [ˈaŋɡliski] 'English').[75] The latter realization is avoided by some speakers who strive for a clear, formal pronunciation.[citation needed]

^2 Inherited Slavic /x/ was lost in the Western dialects of Macedonian on which the standard is based, having become zero initially and mostly /v/ otherwise. /x/ became part of the standard language through the introduction of new foreign words (e.g. хотел, hotel), toponyms (Пехчево, Pehčevo), words originating from Old Church Slavonic (дух, ghost), newly formed words (доход, income) and as a means to disambiguate between two words (храна, food vs. рана, wound). This explains the rarity of Х in the Macedonian language.[75]

^3 They exhibit different pronunciations depending on dialect. They are dorso-palatal stops in the standard language and are pronounced as such by some native speakers.[75]

Stress

The word stress in Macedonian is antepenultimate and dynamic (expiratory). This means that it falls on the third from last syllable in words with three or more syllables, and on the first or only syllable in other words. This is sometimes disregarded when the word has entered the language more recently or from a foreign source.[77] To note which syllable of the word should be accented, Macedonian uses an apostrophe over its vowels. Disyllabic words are stressed on the second-to-last syllable: дéте ([ˈdɛtɛ]: child), мáјка ([ˈmajka]: mother) and тáтко ([ˈtatkɔ]: father). Trisyllabic and polysyllabic words are stressed on the third-to-last syllable: плáнина ([ˈpɫanina]: mountain) планѝната ([pɫaˈninata]: the mountain) планинáрите ([pɫaniˈnaritɛ]: the mountaineers).[77] There are several exceptions to the rule and they include: verbal adverbs (i.e. words suffixed with -ќи): e.g. викáјќи ([viˈkajci]: shouting), одéјќи ([ɔˈdɛjci]: walking); adverbs of time: годинáва ([godiˈnava]: this year), летóво ([leˈtovo]: this summer); foreign loanwords: e.g. клишé ([kliˈʃɛ:] cliché), генéза ([ɡɛˈnɛza] genesis), литератýра ([litɛraˈtura]: literature), Алексáндар ([alɛkˈsandar], Alexander).[78]

Linking occurs when two or more words are pronounced with the same stress. Linking is a common feature of the Macedonian language. This linguistic phenomenon is called акцентска целост and is denoted with a spacing tie (‿) sign. Several words are taken as a single unit and thus follow the rules of the stress falling on the antepenultimate syllable. The rule applies when using clitics (either enclitics or proclitics) such as the negating particle не with verbs (тој нé‿дојде, he did not come) and with short pronoun forms. The future particle ќе can also be used in-between and falls under the same rules (не‿му‿јá‿даде, did not give it to him; не‿ќé‿дојде, he will not come).[79] Other uses include the imperative form accompanied by short pronoun forms (дáј‿ми: give me), the expression of possessives (мáјка‿ми), prepositions followed by a noun (зáд‿врата), question words followed by verbs (когá‿дојде) and some compound nouns (сувó‿грозје - raisins, киселó‿млеко - yoghurt) among others.[79]

Grammar

Macedonian grammar is markedly analytic in comparison with other Slavic languages, having lost the common Slavic case system. The Macedonian language shows some special and, in some cases, unique characteristics due to its central position in the Balkans. Literary Macedonian is the only South Slavic literary language that has three forms of the definite article, based on the degree of proximity to the speaker, and a perfect tense formed by means of an auxiliary verb "to have", followed by a past participle in the neuter, also known as the verbal adjective. Other features that are only found in Macedonian and not in other Slavic languages include the antepenultimate accent and the use of the same vocal ending for all verbs in first person, present simple (глед-a-м, јад-а-м, скок-а-м).[80] Macedonian distinguishes at least 12 major word classes, five of which are modifiable and include nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numbers and verbs and seven of which are invariant and include adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections, particles and modal words.[74]

Nouns

Macedonian nouns (именки) belong to one of three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter) and are inflected for number (singular and plural), and marginally for case. The gender opposition is not distinctively marked in the plural.[81] Masculine nouns usually end in a consonant or a vowel (-a, -o or -e) and neuter nouns end in a vowel (-o or -e). Virtually all feminine nouns end in the same vowel, -a.[79]

The vocative of nouns is the only remaining case in the Macedonian language and is used to address a person directly. The vocative case always ends with a vowel, which can be either an -у (јунаку: hero vocative) or an -e (човече: man vocative) to the root of masculine nouns. For feminine nouns, the most common final vowel ending in the vocative is -o (душо, sweetheart vocative; жено, wife vocative). The final suffix -e can be used in the following cases: three or polysyllabic words with the ending -ица (мајчице, mother vocative), female given names that end with -ка: Ратка becomes Ратке and -ја: Марија becomes Марије or Маријо. There is no vocative case in neuter nouns. The role of the vocative is only facultative and there is a general tendency of vocative loss in the language since its use is considered impolite and dialectal.[82] The vocative can also be expressed by changing the tone.[79][83]

There are three different types of plural: regular, counted and collective. The first plural type is most common and used to indicate regular plurality of nouns: маж - мажи (a man - men), маса - маси (a table - table), село - села (a village - villages). There are various suffixes that are used and they differ per gender; a linguistic feature not found in other Slavic languages is the use of the suffix -иња to form plural of neuter nouns ending in -е: пиле - пилиња (a chick - chicks).[80] Counted plural is used when a number or a quantifier precedes the noun; suffixes to express this type of plurality do not correspond with the regular plurality suffixes: два молива (two pencils), три листа (three leaves), неколку часа (several hours). The collective plural is used for nouns that can be viewed as a single unit: лисје (a pile of leaves), ридје (a unit of hills). Irregular plural forms also exist in the language: дете - деца (child - children).[79]

Definiteness

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Unspecified | мажот | жената | детето | мажите/жените | децата | |

| Proximate | мажов | женава | детевo | маживе/жениве | децава | |

| Distal | мажон | женана | детенo | мажине/женине | децана | |

A characteristic feature of the nominal system is the indication of definiteness. As with other Slavic languages, there is no indefinite article in Macedonian. The definite article in Macedonian is postpositive, i.e. it is added as a suffix to nouns. An individual feature of the Macedonian language is the use of three definite articles, inflected for gender and related to the position of the object, which can be unspecified, proximate or distal.

- Definite articles -ов, -ва, -во, -ве are used for objects located close to the speaker (човеков: - this person here)

- Definite articles -он, -на, -но, -не are used for objects located further away from the speaker that can still be perceived (женана: - that woman there)

- Definite articles -от, -та, -то, -те are most commonly used as general indicators of definiteness regardless of the referred object's position (детето: the child). Additionally, these suffixes can be used to indicate objects referred to by the speaker that are in the proximity of the listener, e.g. дај ми ја книгата што е до тебе - give me the book next to you.[74]

Proper nouns are per definition definite and are not usually used together with an article, although exceptions exist in the spoken and literary language such as Совчето, Марето, Надето to demonstrate feelings of endearment to a person.

Adjectives

Adjectives accompany nouns and serve to provide additional information about their referents. Macedonian adjectives agree in form with the noun they modify and are thus inflected for gender, number and definiteness and убав changes to убава (убава жена, a beautiful woman) when used to describe a feminine noun, убаво when used to describe a neuter noun (убаво дете, a beautiful child) and убави when used to form the plural (убави мажи, убави жени, убави деца).[79]

Adjectives can be analytically inflected for degree of comparison with the prefix по- marking the comparative and the prefix нај- marking the superlative. Both prefixes cannot be written separately from the adjective: Марија е паметна девојка (Marija is a smart girl), Марија е попаметна од Сара (Marija is smarter than Sara), Марија е најпаметната девојка во нејзиниот клас (Marija is the smartest girl in her class). The only adjective with an irregular comparative and superlative form is многу which becomes повеќе in the comparative and најмногу in the superlative form.[84] Another modification of adjectives is the use of the prefixes при- and пре- which can also be used as a form of comparison: престар човек (a very old man) or пристар човек (a somewhat old man).[74]

Pronouns

Three types of pronouns can be distinguished in Macedonian: personal (лични), relative (лично-предметни) and demonstrative (показни). Case relations are marked in pronouns. Personal pronouns in Macedonian appear in three genders and both in singular and plural. They can also appear either as direct or indirect object in long or short forms. Depending on whether a definite direct or indirect object is used, a clitic pronoun will refer to the object with the verb: Јас не му ја дадов книгата на момчето ("I did not give the book to the boy").[85] The direct object is a remnant of the accusative case and the indirect of the dative. Reflexive pronouns also have forms for both direct and indirect objects: себе се, себе си. Examples of personal pronouns are shown below:

- Personal pronoun: Јас читам книга. ("I am reading a book")

- Direct object pronoun: Таа мене ме виде во киното. ("She saw me at the cinema")

- Indirect object pronoun: Тој мене ми рече да дојдам. ("He told me to come")

Relative pronouns can refer to a person (кој, која, кое - who), objects (што - which) or serve as indicators of possession (чиј, чија, чие - whose) in the function of a question or a relative word. These pronouns are inflected for gender and number and other word forms can be derived from them (никој - nobody, нешто - something, сечиј - everybody's). There are three groups of demonstrative pronouns that can indicate proximate (овој - this one (mas.)), distal (онаа - the one there (fem.)) and unspecific (тоа - that one (neut.)) objects. These pronouns have served as a basis for the definite article.[74][79]

| Person | Singular | Direct object | Indirect object | Plural | Direct object | Indirect object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | јас | мене ме | мене ми | ние | нас нѐ | нам ни |

| 2. | ти вие (formal) |

тебе те вас ве (formal) |

тебе ти вас ви (formal) |

вие | вас ве | вас ви |

| 3. | тој (masculine) таа (feminine) тоа (neuter) |

него го (masc./neut.) неа ја (fem.) |

нему му (masc./neut.) нејзе ѝ (fem.) |

тие | нив ги | ним им |

Verbs

Macedonian verbs agree with the subject in person (first, second or third) and number (singular or plural). Some dependent verb constructions (нелични глаголски форми) such as verbal adjectives (глаголска придавка: плетен/плетена), verbal l-form (глаголска л-форма: играл/играла) and verbal noun (глаголска именка: плетење) also demonstrate gender. There are several other grammatical categories typical of Macedonian verbs, namely type, transitiveness, mood, superordinate aspect (imperfective/perfective aspect).[86] Verb forms can also be classified as simple, with eight possible verb constructions or complex with ten possible constructions.[79]

Macedonian has developed a grammatical category which specifies the opposition of witnessed and reported actions (also known as renarration). Per this grammatical category, one can distinguish between минато определено i.e. definite past, denoting events that the speaker witnessed at a given definite time point, and минато неопределено i.e. indefinite past denoting events that did not occur at a definite time point or events reported to the speaker, excluding the time component in the latter case. Examples: Но, потоа се случија работи за кои не знаев ("But then things happened that I did not know about") vs. Ми кажаа дека потоа се случиле работи за кои не знаев ("They told me that after, things happened that I did not know about").[87]

Tense

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | сум, бев, сум бил, ќе бидам | сме, бевме, сме биле, ќе бидеме |

| 2. | си, беше, си бил, ќе бидеш | сте, бевте, сте биле, ќе бидете |

| 3. | е, беше, бил, ќе биде | се, беа, биле, ќе бидат |

The present tense in Macedonian is formed by adding a suffix to the verb stem which is inflected per person, form and number of the subject. Macedonian verbs are conventionally divided into three main conjugations according to the thematic vowel used in the citation form (i.e. 3p-pres-sg).[74] These groups are: a-group, e-group and и-group. Furthermore, the и-subgroup is divided into three more subgroups: а-, е- and и-subgroups. The verb сум (to be) is the only exception to the rule as it ends with a consonant and is conjugated as an irregular verb.

The perfect tense can be formed using both to be (сум) and to have (има) as auxiliary verbs. The first form inflects the verb for person and uses a past active participle: сум видел многу работи ("I have seen a lot of things"). The latter form makes use of a clitic that agrees in number and gender with the object of the sentence and the passive participle of the verb in its uninflected form (го имам гледано филмот, "I have seen that movie").[41][86] Another past form, the aorist is used to describe actions that have finished at a given moment in the past: одев ("I walked"), скокаа ("they jumped").[79]

Future forms of verbs are conjugated using the particle ќе followed by the verb conjugated in present tense, ќе одам (I will go). The construction used to express negation in the future can be formed by either adding the negation particle at the beginning не ќе одам (I will not go) or using the construction нема да (нема да одам). There is no difference in meaning, although the latter form is more commonly used in spoken language. Another future tense is future in the past which is formed using the clitic ќе and the past tense of the verb inflected for person, таа ќе заминеше ("she would have left").[79]

Aspect, voice and mood

Similar to other Slavic languages, Macedonian verbs have a grammatical aspect (глаголски вид) that is a typical feature of Slavic languages. Verbs can be divided into imperfective (несвршени) and perfective (свршени) indicating actions whose time duration is unknown or occur repetitively or those that show an action that is finished in one moment. The former group of verbs can be subdivided into verbs which take place without interruption (e.g. Тој спие цел ден, "He sleeps all day long) or those that signify repeated actions (e.g. Ја бараше книгата но не можеше да ја најде, "He was looking for the book but he could not find it"). Perfective verbs are usually formed by adding prefixes to the stem of the verb, depending on which, they can express actions that took place in one moment (чукна, "knocked"), actions that have just begun (запеа, "start to sing"), actions that have ended (прочита, "read") or partial actions that last for short periods of time (поработи, "worked").[79]

The contrast between transitive and intransitive verbs can be expressed analytically or syntactically and virtually all verbs denoting actions performed by living beings can become transitive if a short personal pronoun is added: Тоj легна ("He laid down") vs. Тоj го легна детето ("He laid the child down"). Additionally, verbs which are expressed with the reflexive pronoun се can become transitive by using any of the contracted pronoun forms for the direct object: Тој се смее - He is laughing, vs. Тој ме смее - "He is making me laugh"). Some verbs such as sleep or die do not traditionally have the property of being transitive.[88]

Macedonian verbs have three grammatical moods (глаголски начин): indicative, imperative and conditional. The imperative mood can express both a wish or an order to finish a certain action. The imperative only has forms for the second person and is formed using the suffixes -ј (пеј; sing) or -и (оди, walk) for singular and -јте (пејте, sing) or -ете for plural (одете, walk). The first and third subject forms in singular and plural express indirect orders and are conjugated using да or нека and the verb in present tense (да живееме долго, may we live long). In addition to its primary functions, the imperative is used to indicate actions in the past, eternal truths as is the case in sayings and a condition. The Macedonian conditional is conjugated in the same way for all three persons using the particle би and the verbal l-form, би читал (I/you/he would read).[79]

Syntax

Macedonian syntax has a subject-verb-object (SVO) word order which is nevertheless flexible and can be topicalized.[71] For instance, the sentence Марија го сака Иван (Marija loves Ivan) can become of the object–verb–subject (OVS) form as well, Иван го сака Марија.[89] Topicalization can also be achieved using a combination of word order and intonation; as an example all of the following sentences give a different point of emphasis:

- Мачката ја каса кучето. – The dog bites the cat (the focus is on the object)

- Кучето мачката ја каса. – The dog bites the cat (the focus is on the object)

- Мачката кучето ја каса. – The dog bites the cat (the focus is on the subject)

- Ја каса кучето мачката. – The dog bites the cat (the focus is on both the subject and the verb)

- Ја каса мачката кучето. – The dog bites the cat (the focus is on the verb and the object)[90]

Macedonian is a null-subject language which means that the subject pronoun can be omitted, for instance Што сакаш (ти)? (what do you want?), (јас) читам книга (I am reading a book), (ние) го видовме (we saw him).[89] Macedonian passive construction is formed using the short reflexive pronoun се (девојчето се уплаши, the girl got scared) or a combination of the verb "to be" with verbal adjectives (Тој е миен, he is washed). In the former case, the active-passive distinction is not very clear.[88] Subordinate clauses in Macedonian are introduced using relativizers, which can be wh-question words or relative pronouns.[91] A glossed example of this is:

човек-от

person-DEF

со

with

кого(што)

whom(that)

се

ITR

шета-ше

stroll-3SG.IM

вчера

yesterday

the person with whom he walked yesterday[91]

Due to the absence of a case system, Macedonian makes wide use of prepositions (предлози) to express relationships between words in a sentence. The most important Macedonian preposition is на which can have local ('on') or motional meanings ('to').[92] As a replacement for the dative case, the preposition на is used in combination with a short indirect object form to denote an action that is related to the indirect object of a sentence, Му давам книга на Иван (I am giving a book to Ivan), Им велам нешто на децата (I am saying something to the children).[89] Additionally, на can serve to replace the genitive case and express possession, таткото на другар ми (my friend's father).[92]

Vocabulary

Macedonian exhibits lexical similarities with all other Slavic languages, and numerous nouns are cognates, including those related to familial relations and numbers.[80] Additionally, as a result of the close relationship with Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian shares a considerable amount of its lexicon with these languages. Other languages that have been in positions of power, such as Ottoman Turkish and, increasingly, English have also provided a significant proportion of the loanwords. Prestige languages, such as Old Church Slavonic—which occupies a relationship to modern Macedonian comparable to the relationship of medieval Latin to modern Romance languages—and Russian also provided a source for lexical items. Other loanwords and vocabulary also came from Greek and Albanian as well as prestige languages such as French and German.[93][94]

During the standardization process, there was deliberate care taken to try to purify the lexicon of the language. Words that were associated with the Serbian or Bulgarian standard languages, which had become common due to the influence of these languages in the region, were rejected in favor of words from native dialects and archaisms. This is not to say that there are no words associated with the Serbian, Bulgarian, or even Russian standard languages in the language, but rather that they were discouraged on a principle of "seeking native material first".[95]

The language of the writers at the turn of the 19th century abounded with Russian and, more specifically, Old Church Slavonic lexical and morphological elements that in the contemporary norm have been replaced by native words or calqued using productive morphemes.[96] New words were coined according to internal logic and others calqued from related languages (especially Serbo-Croatian) to replace those taken from Russian, which include известие (Russ. известие) → извештај 'report', количество (Russ. количество) → количина 'amount, quantity', согласие (Russ. согласие) → слога 'concord, agreement', etc.[96] This change was aimed at bringing written Macedonian closer to the spoken language, effectively distancing it from the more Russified Bulgarian language, representing a successful puristic attempt to abolish a lexicogenic tradition once common in written literature.[96] The use of Ottoman Turkish loanwords is discouraged in the formal register when a native equivalent exists (e.g. комшија (← Turk. komşu) vs. сосед (← PSl. *sǫsědъ) 'neighbor'), and these words are typically restricted to the archaic, colloquial, and ironic registers.[97]

| English | Macedonian | Bulgarian | Serbian | Croatian | Slovenian | Russian | Belarusian | Ukrainian | Polish | Czech | Slovak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dream | сон son |

сън sŭn |

сан san |

san | sen | сон son |

сон son |

сон son |

sen | sen | sen |

| day | ден den |

ден den |

дан dan |

dan | dan | день den' |

дзень dzień |

день den |

dzień | den | den |

| arm | рака raka |

ръка rŭka |

рука ruka |

ruka | roka | рука ruka |

рука ruka |

рука ruka |

ręka | ruka | ruka |

| flower | цвет cvet |

цвят tsvyat |

цвет cvet |

cvijet | cvet | цветок tsvetok |

кветка kvietka |

квітка kvitka |

kwiat | květ/květina | kvet/kvetina |

| night | ноќ nokj |

нощ nosht |

ноћ noć |

noć | noč | ночь noch' |

ноч noč |

нiч nich |

noc | noc | noc |

Writing system

Alphabet

The official Macedonian alphabet was codified on 5 May 1945 by the Presidium of the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (abbreviated as ASNOM in Macedonian) headed by Blaže Koneski.[99] There are several letters that are specific for the Macedonian Cyrillic script, namely ѓ, ќ, ѕ, џ, љ and њ,[61] with the last three letters being borrowed from the Serbo-Croatian phonetic alphabet adapted by Serbian linguist Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, while the grapheme ѕ has an equivalent in the Church Slavonic alphabet.[100] Letters љ and њ were previously used by Macedonian writer Krste Petkov Misirkov written as л' and н'.[99] The Macedonian alphabet also uses the apostrophe sign (') as a sound. It is used to mark the syllable forming /р˳/ , at the beginning of the word ('рж - rye, 'рбет - spine) and to represent the phoneme schwa in some literary words or Turkish loanwords ('к'смет - fortune). А grave accent (`) diacritic is used over three vowels in orthography: ѝ - her, different from и - and, нè - us, different from не - no and сѐ - everything different from сe - short reflexive pronoun accompanying reflexive verbs.[61] The standard Macedonian alphabet contains 31 letters. The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Macedonian alphabet, along with the IPA value for each letter:

| Cyrillic IPA |

А а /a/ |

Б б /b/ |

В в /v/ |

Г г /ɡ/ |

Д д /d/ |

Ѓ ѓ /ɟ/ |

Е е /ɛ/ |

Ж ж /ʒ/ |

З з /z/ |

Ѕ ѕ /d͡z/ |

И и /i/ |

| Cyrillic IPA |

Ј ј /j/ |

К к /k/ |

Л л /ɫ, l/[101] |

Љ љ /l/[101] |

М м /m/ |

Н н /n/ |

Њ њ /ɲ/ |

О о /ɔ/ |

П п /p/ |

Р р /r/ |

С с /s/ |

| Cyrillic IPA |

Т т /t/ |

Ќ ќ /c/ |

У у /u/ |

Ф ф /f/ |

Х х /x/ |

Ц ц /t͡s/ |

Ч ч /t͡ʃ/ |

Џ џ /d͡ʒ/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ |

Orthography

Similar to the Macedonian alphabet, Macedonian orthography was officially codified on 7 June 1945 at an ASNOM meeting.[99] Rules about the orthography and orthoepy (correct pronunciation of words) were first collected and outlined in the book Правопис на македонскиот литературен јазик (Orthography of the Macedonian standard language) published in 1945. Updated versions have subsequently appeared with the most recent one published in 2016.[102] Macedonian orthography is consistent and phonemic in practice, an approximation of the principle of one grapheme per phoneme. This one-to-one correspondence is often simply described by the principle, "write as you speak and read as it is written".[71] There is only one exception to this rule with the letter /л/ which is pronounced as /l/ before front vowels (e.g. лист (leaf); pronounced as [list]) and /j/ (e.g. полјанка (meadow); pronounced as [poljanka]) but velar /ł/ elsewhere (e.g. бела (white) pronounced as [beła]). Another sound that is not represented in the written form but is pronounced in words is the schwa.[71]

Political views on the language

Politicians and scholars from North Macedonia, Bulgaria and Greece have opposing views about the existence and distinctiveness of the Macedonian language. Through history Macedonian has been referred mainly to as a variant of Bulgarian,[103] but especially during the first half of the 20th century also as Serbian,[104] and as a distinct language of its own.[105][106] Historically, after its codification, the use of the language has been a subject of different views and internal policies in Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece.[35][107] Some international scholars also maintain Macedo-Bulgarian was a single pluricentric language until the 20th century and argue that the idea of linguistic separatism emerged in the late 19th century with the advent of Macedonian nationalism and the need for a separate Macedonian standard language subsequently appeared in the early 20th century.[108] Different linguists have argued that during its codification, the Macedonian standard language was Serbianized with regards to its orthography[109][110][111][112][113] and vocabulary.[114]

The government of Bulgaria, Bulgarian academics, the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and the general public have and continue to widely consider Macedonian part of the Bulgarian dialect area.[1][115][116] During the Communist era, Macedonian was recognized as a minority language in Bulgaria and utilized in education from 1946 to 1948. Subsequently, it was described as a dialect of Bulgarian.[117] In 1956 the Bulgarian government signed an agreement on mutual legal defense with Yugoslavia, where the Macedonian language is named as one of the languages to be used for legal purposes, together with Bulgarian, Serbo-Croatian and Slovenian.[118] The same year Bulgaria revoked its recognition of Macedonian nationhood and language and implicitly resumed its prewar position of their non-existence.[119] In 1999 the government in Sofia signed a Joint Declaration in the official languages of the two countries, marking the first time it agreed to sign a bilateral agreement written in Macedonian.[120] Dialect experts of the Bulgarian language refer to the Macedonian language as македонска езикова норма (Macedonian linguistic norm) of the Bulgarian language.[9] As of 2019, disputes regarding the language and its origins are ongoing in academic and political circles in the two countries.

The Greek scientific and local community opposed using the denomination Macedonian to refer to the language in light of the Greek-Macedonian naming dispute. Instead, the language is often called "Slavic", "Slavomacedonian" (translated to "Macedonian Slavic" in English), makedonski, makedoniski ("Macedonian"),[121] slaviká (Greek: "Slavic"), dópia or entópia (Greek: "local/indigenous [language]"),[122] balgàrtzki (Bulgarian) or "Macedonian" in some parts of the region of Kastoria,[123] bògartski ("Bulgarian") in some parts of Dolna Prespa[124] along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old").[121] However, with the Prespa agreement signed in June 2018 and ratified by the Greek Parliament on 25 January 2019, Greece officially recognized the name "Macedonian" for the language.[125] Additionally, on 27 July 2022,[126] in a landmark ruling, the Centre for the Macedonian Language in Greece was officially registered as a non-governmental organization. This is the first time that a cultural organization promoting the Macedonian language has been legally approved in Greece and the first legal recognition of the Macedonian language in Greece since at least 1928.[127][128][129][130]

Sample text

The following is the Lord's Prayer in standard Macedonian.

|

|

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Macedonian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ a b "Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 – European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ a b "European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b Nikolovski, Valentin (30 October 2016). "Македонците во Србија ги уживаат сите малцински права, како и србите во Македонија" [Macedonians in Serbia have all the minority rights just as Serbians in Macedonia] (in Macedonian). Sitel. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. (1995). Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 143. ISBN 0312121164.

The obviously plagiarized historical argument of the Macedonian nationalists for a separate Macedonian ethnicity could be supported only by linguistic reality, and that worked against them until the 1940s. Until a modern Macedonian literary language was mandated by the communist-led partisan movement from Macedonia in 1944, most outside observers and linguists agreed with the Bulgarians in considering the vernacular spoken by the Macedonian Slavs as a western dialect of Bulgarian

- ^ Thornburg & Fuller 2006, p. 213.

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/topic/Slavic-languages/Grammatical-characteristics

- ^ Siewierska, Anna, and Ludmila Uhlirova. "An overview of word order in Slavic languages." Empirical approaches to language typology 20 (1998): 105-150.

- ^ a b Reimann 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Trudgill 1992.

- ^ Raúl Sánchez Prieto, Politics shaping linguistic standards: the case of Dutch in Flanders and Bulgaro-Macedonian in the Republic of Macedonia, in: Exploring linguistic standards in non-dominant varieties of pluricentric languages, ISBN 3631625839, pp.227-244; Peter Lang, with Carla Amoros Negre et al. as eds.

- ^ "5 мај – Ден на македонскиот јазик". Филолошки факултет "Блаже Конески" – Скопје (in Macedonian). Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "Од 130-тата седница на Владата на РСМ: 5 Мај прогласен за Ден на македонскиот јазик". Влада на Република Северна Македонија (in Macedonian). 16 April 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Friedman, Garry & Rubino 2001, p. 435.

- ^ Levinson & O'Leary 1992, p. 239.

- ^ Dedaić & Mišković-Luković 2010, p. [page needed].

- ^ Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011, p. 420.

- ^ a b c Topolinjska 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Fortson 2009, p. 431.

- ^ Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 245.

- ^ Campbell 2000, pp. 274, 1031.

- ^ Chambers, J.K.; Trudgill, Peter (1998), Dialectology (2nd ed., Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 169–170, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511805103, ISBN 9780521593786

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi, Catherine Gibson as ed., The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, Springer, 2016; ISBN 1137348399, p. 436.

- ^ a b Lindstedt, Jouko (2016). "Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area". The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. pp. 429–447. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-34839-5_21. ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3.

Macedonian dialectology... considers the dialects of south-western Bulgaria to be Macedonian, despite the lack of any widespread Macedonian national consciousness in that area. The standard map is provided by Vidoeski.(1998: 32) It would be futile to tell an ordinary citizen of the Macedonian capital, Skopje, that they do not realise that they are actually speaking Bulgarian. It would be equally pointless to tell citizens of the southwestern Bulgarian town of Blagoevgrad that they (or at least their compatriots in the surrounding countryside) do not 'really' speak Bulgarian, but Macedonian. In other words, regardless of the structural and linguistic arguments put forth by a majority of Bulgarian dialectologists, as well as by their Macedonian counterparts, they are ignoring one, essential fact – that the present linguistic identities of the speakers themselves in various regions do not always correspond to the prevailing nationalist discourses.

- ^ Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- ^ Riki van Boeschoten is a retired professor of the University of Thessaly and director of the Laboratory of Social Anthropology and the Oral History Archive dialects in eastern Greek Macedonia. Riki van Boeschoten - My CV. , Her work (2013)

- ^ Boeschoten, Riki van (1993): Minority Languages in Northern Greece. Study Visit to Florina, Aridea, (Report to the European Commission, Brussels) "The Western dialect is used in Florina and Kastoria and is closest to the language used north of the border, the Eastern dialect is used in the areas of Serres and Drama and is closest to Bulgarian, the Central dialect is used in the area between Edessa and Salonica and forms an intermediate dialect"

- ^ Ioannidou, Alexandra (1999). Questions on the Slavic Dialects of Greek Macedonia. Athens: Peterlang. pp. 59, 63. ISBN 9783631350652.

In September 1993 ... the European Commission financed and published an interesting report by Riki van Boeschoten on the "Minority Languages in Northern Greece", in which the existence of a "Macedonian language" in Greece is mentioned. The description of this language is simplistic and by no means reflective of any kind of linguistic reality; instead it reflects the wish to divide up the dialects comprehensibly into geographical (i.e. political) areas. According to this report, Greek Slavophones speak the "Macedonian" language, which belongs to the "Bulgaro-Macedonian" group and is divided into three main dialects (Western, Central and Eastern) - a theory which lacks a factual basis.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Usikova 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Spasov, Ljudmil (2007). "Периодизација на историјата на македонскиот писмен јазик и неговата стандардизација во дваесеттиот век" [Periodization of the history of the Macedonian literary language and its standardization in the twentieth century]. Filološki Studii (in Macedonian). 5 (1). Skopje: St. Cyril and Methodius University: 229–235. ISSN 1857-6060.

- ^ Koneski, Blazhe (1967). Историја на македонскиот јазик [History of the Macedonian Language] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Kultura.

- ^ a b Browne, Wayles; Vsevolodovich Ivanov, Vyacheslav. "Slavic languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Lunt 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Vidoeski 1999, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Friedman, Garry & Rubino 2001, p. 436.

- ^ Usikova 2005, pp. 103, 106.

- ^ a b Friedman, Garry & Rubino 2001, p. 438.

- ^ Kramer 1999, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1999, p. 235.

- ^ Bechev 2009, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Usikova 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Nihtinen 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Nihtinen 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Kramer 1999, p. 236.

- ^ Pejoska-Bouchereau 2008, p. 146.

- ^ "Повелба за македонскиот јазик" [Charter for the Macedonian language] (PDF) (in Macedonian). Skopje: Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Macedonian". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Попис на населението, домаќинствата и становите во Република Македонија, 2002" [Census of the population, households and dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002] (PDF). Book X (in Macedonian and English). Skopje: Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office. May 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Crvenkovska, Emilija; Petroska, Elena. "Македонскиот јазик како втор и странски: терминолошки прашања" [Macedonian as a foreign and second language: terminological questions] (PDF) (in Macedonian). Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Artan Hoxha; Alma Gurraj (2001). "Local Self-Government and Decentralization: Case of Albania. History, Reforms and Challenges". Local Self Government and Decentralization in South - East Europe (PDF). Proceedings of the workshop held in Zagreb, Croatia. 6 April 2001. Zagreb: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. p. 219. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Население по етническа група и майчин език" [Population per ethnic group and mother tongue] (in Bulgarian). Bulgarian Census Bureau. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "2011 Census – Mother tongue". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Hill 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Poulton 2000, p. 167.

- ^ "Language spoken at home - Ranked by size". Profile ID. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Data tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013". United States Census. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Броj на македонски иселеници во светот" [Number of Macedonian immigrants in the world] (in Macedonian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (North Macedonia). Archived from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Naumovski, Jaklina (25 January 2014). "Minorités en Albanie : les Macédoniens craignent la réorganisation territoriale du pays" (in French). Balkan Courriers. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "On the Status of the Minorities in the Republic of Albania" (PDF). Sofia: Albanian Helsinki Committee. 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Usikova 2005, p. 105–106.

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Dedaić & Mišković-Luković 2010, p. 13.

- ^ After Z. Topolińska and B. Vidoeski (1984), Polski-macedonski gramatyka konfrontatiwna, z.1, PAN.

- ^ Topolinjska 1998, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Usikova 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Usikova 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 247.

- ^ Kolomiec, V.T.; Linik, T.G.; Lukinova, T.V.; Meljnichuk, А.S.; Pivtorak, G.P.; Sklyarenko, V.G.; Tkachenko, V.A.; Tkachenko, O.B (1986). Историческая типология славянских языков. Фонетика, слообразование, лексика и фразеология [Historical typology of Slavic languages] (in Ukrainian). Kiev: National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d e f g Friedman 2001.

- ^ a b Friedman 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Lunt 1952, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f Bojkovska et al. 2008, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Friedman 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Lunt 1952, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Usikova 2005, p. 109–110.

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bogdanoska 2008.

- ^ a b c Bojkovska et al. 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Minova Gjurkova, Liljana (1994). Синтакса на македонскиот стандарден јазик [Syntax of the standard Macedonian language] (in Macedonian).

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Friedman, Garry & Rubino 2001, p. 437.

- ^ a b Friedman 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 43.

- ^ a b Usikova 2005, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Usikova 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Friedman 2001, p. 50.

- ^ a b Friedman 2001, p. 58.

- ^ a b Friedman 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. 36.

- ^ Usikova 2005, p. 136.

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c Т. Димитровски. Литературната лексика на македонскиот писмен јазик во XIX в. и нашиот однос кон неа: Реферати на македонските слависти за VI Меѓународен славистички конгрес во Прага, Скопје, 1968 (T. Dimitrovski. The literary vocabulary of the Macedonian written language in the 19th century and our attitude to it. Abstracts of Macedonian Slavists for the 6th International Slavic Studies Congress in Prague. Skopje, 1968)

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Bojkovska et al. 2008, p. 44.

- ^ a b c "Со решение на АСНОМ: 72 години од усвојувањето на македонската азбука" [With the declaration of ASNOM: 72 years of the adoption of the Macedonian alphabet]. Javno (in Macedonian). 5 May 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Friedman 1993, p. 251.

- ^ a b ⟨л⟩ is pronounced /l/ before /e, i, j/, and /ɫ/ otherwise. ⟨љ⟩ is always pronounced /l/ but is not used before /e, i, j/. Cf. how the final љ in биљбиљ /ˈbilbil/ "nightingale" is changed to a л in the plural form биљбили /ˈbilbili/.

- ^ "Правописот на македонски јазик од денес бесплатно на интернет" [The orthography of the Macedonian language for free on the Internet from today]. sdk.mk. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Institute of Bulgarian Language (1978). Единството на българския език в миналото и днес [The unity of the Bulgarian language in the past and today] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. OCLC 6430481.

- ^ Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 251.

- ^ Adler 1980, p. 215.

- ^ Seriot 1997, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Kramer 1999, pp. 237–245.

- ^ Fishman 1993, p. 161–162.

- ^ Friedman 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Marinov, Tchavdar (25 May 2010). "Historiographical Revisionism and Re-Articulation of Memory in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (PDF). Sociétés Politiques Comparées. 25: 7. S2CID 174770777. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Voss C., The Macedonian Standard Language: Tito—Yugoslav Experiment or Symbol of 'Great Macedonian' Ethnic Inclusion? in C. Mar-Molinero, P. Stevenson as ed. Language Ideologies, Policies and Practices: Language and the Future of Europe, Springer, 2016, ISBN 0230523889, p. 126.

- ^ De Gruyter as contributor. The Slavic Languages. Volume 32 of Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science (HSK), Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2014, p. 1472. ISBN 3110215470.

- ^ Lerner W. Goetingen, Formation of the standard language - Macedonian in the Slavic languages, Volume 32, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, 2014, ISBN 3110393689, chapter 109.

- ^ Voß 2018, p. 9.

- ^ "Bulgarian Academy of Sciences is firm that "Macedonian language" is Bulgarian dialect". Bulgarian National Radio. 12 November 2019. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Jakov Marusic, Sinisa (10 October 2019). "Bulgaria Sets Tough Terms for North Macedonia's EU Progress". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Ranko Bugarski, Celia Hawkesworth as editors, Language in the Former Yugoslav Lands, Slavica Publishers, 2004, ISBN 0893572985, p. 201.

- ^ "Agreement between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia for mutual legal defense". Държавен вестник No 16. 22 February 1957. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ Raymond Detrez, (2010) The A to Z of Bulgaria, Issue 223 of A to Z Guides, Edition 2, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 0810872021.

- ^ Kramer 1999.

- ^ a b Whitman 1994, p. 37.

- ^ "Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities". Greek Helsinki Monitor. Archived from the original on 23 May 2003. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Danforth 1995, p. 62.

- ^ Shklifov, Blagoy; Shklifova, Ekaterina (2003). Български деалектни текстове от Егейска Македония [Bulgarian dialect texts from Aegean Macedonia] (in Bulgarian). Sofia. pp. 28–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Republic of North Macedonia with Macedonian language and identity, says Greek media". Meta.mk. Meta. 12 June 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Judicial victory for the Macedonian language in Greece: The court in Lerin rejected the lawsuits to ban the Macedonian Language Center in Greece". Sloboden Pečat. 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Грција го регистрираше центарот за македонски јазик" [Greece Registered the Macedonian-language Center] (in Macedonian). Deutsche Welle. 29 November 2022.

- ^ ""Центарот на македонскиот јазик во Грција" официјално регистриран од судските власти" ["The Center of Macedonian language in Greece" officially registered by court laws] (in Macedonian). Sloboden Pecat. 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Εγκρίθηκε «Κέντρο Μακεδονικής Γλώσσας» στην Φλώρινα: Ευχαριστίες Ζάεφ σε Τσίπρα - Μητσοτάκη" ["Centre for Macedonian Language" was approved in Florina: Zaev thanks Tsipras - Mitsotakis] (in Greek). Ethnos. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Mavrogordatos, George. Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922–1936. University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 9780520043589, p. 227, 247

References

- Books

- Adler, Max K. (1980), Marxist Linguistic Theory and Communist Practice: A Sociolinguistic Study, Buske Verlag, ISBN 3871184195

- Bechev, Dimitar (13 April 2009), Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1

- Bogdanoska, Biljana (2008), За матуранти македонски јазик и литература [Macedonian language and literature for matura students] (in Macedonian), Skopje: Bomat Grafiks

- Bojkovska, Stojka; Minova-Gjurkova, Liljana; Pandev, Dimitar; Cvetanovski, Živko (2008), Општа граматика на македонскиот јазик [Grammar of the Macedonian language] (in Macedonian), Skopje: Prosvetno Delo, ISBN 9789989006623

- Campbell, George L. (2000), Compendium of the World's Languages, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415202965

- Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville (2002), "The Macedonian language", The Slavonic Languages, New York: Routledge Publications

- Dedaić, Mirjana N.; Mišković-Luković, Mirjana (2010), South Slavic Discourse Particles, Pragmatics & Beyond New Series, vol. 197, Amsterdam: Benjamins, doi:10.1075/pbns.197, ISBN 978-90-272-5601-0

- Danforth, Loring M. (1995), The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- Fishman, Joshua A. (1993), The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: The "First Congress" Phenomenon, Mouton De Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-013530-2

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (31 August 2009), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction Blackwell textbooks in linguistics, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-1-4051-8896-8

- Friedman, Victor (1993), "Macedonian", in Comrie B.; Corbett G. (eds.), The Slavonic Languages, London, New York: Routledge, pp. 249–305, ISBN 0-415-04755-2

- Friedman, Victor (2001), Macedonian, Slavic and Eurasian Language Resource Center (SEELRC), Duke University, archived from the original on 28 July 2014, retrieved 3 February 2006

- Friedman, Victor (2001), Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.), Macedonian: Facts about the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the Worlds Major Languages, Past and Present (PDF), New York: Holt, pp. 435–439, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2019, retrieved 18 March 2020

- Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan (27 July 2011), Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide, Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, ISBN 978-3-11-022025-4

- Levinson, David; O'Leary, Timothy (1992), Encyclopedia of World Cultures, G.K. Hall, ISBN 0-8161-1808-6

- Lunt, Horace G. (1952), A Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language, Skopje: Državno knigoizdatelstvo

- Lunt, Horace Gray (2001), Old Church Slavonic Grammar, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110162849

- Poulton, Hugh (2000), Who Are the Macedonians?, United Kingdom: C. Hurst & Co., ISBN 0-253-34598-7

- Reimann, Daniel (2014), Kontrastive Linguistik und Fremdsprachendidaktik Iberoromanisch (in German), Gunter Narr Verlag, ISBN 978-3823368250

- Thornburg, Linda L.; Fuller, Janet M. (2006), Studies in contact linguistics: Essays in Honor of Glenn G. Gilbert, New York: Peter Lung Publishing Inc., ISBN 978-0-8204-7934-7

- Topolińska, Zuzanna (1984), Polski-macedoński, gramatyka konfrontatywna: Zarys problematyki [Polish-Macedonian, confrontational grammar] (in Polish), Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, ISBN 978-8304016682

- Usikova, Rina Pavlovna (1994), О языковой ситуации в Республике Македонии [About the language situation in the Republic of Macedonia] (in Russian), Moscow: Nauka, pp. 221–231, ISBN 5-02-011187-2

- Usikova, Rina Pavlovna (2005), Языки мира. Славянские языки: Македонский язык [Languages of the world. Slavic languages: Macedonian language] (in Russian), Moscow: Academia, pp. 102–139, ISBN 5-87444-216-2

- Vidoeski, Bozhidar (1999), Дијалектите на македонскиот јазик: том 1 [The dialects of the Macedonian language: Book 1] (in Macedonian), MANU, ISBN 9989649634

- Whitman, Lois (1994), Denying ethnic identity: The Macedonians of Greece, New York: Helsinki Human Rights Watch, ISBN 1564321320

- Journal articles

- Hill, P. (1999), "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A comparative study of recent developments", Nationalities Papers, 27 (1): 17, doi:10.1080/009059999109163, S2CID 154201780

- Friedman, Victor (1998), "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results", International Journal of the Sociology of Language (131): 31–57, doi:10.1515/ijsl.1998.131.31, S2CID 143891784

- Kramer, Christina (1999), "Official Language, Minority Language, No Language at All: The History of Macedonian in Primary Education in the Balkans", Language Problems and Language Planning, 23 (3): 233–250, doi:10.1075/lplp.23.3.03kra

- Nihtinen, Atina (1999), "Language, Cultural Identity and Politics in the Cases of Macedonian and Scots", Slavonica, 5 (1): 46–58, doi:10.1179/sla.1999.5.1.46

- Pejoska-Bouchereau, Frosa (2008), "Histoire de la langue macédonienne" [History of the Macedonian language], Revue des études slaves (in French), pp. 145–161

- Seriot, Patrick (1997), "Faut-il que les langues aient un nom? Le cas du macédonien" [Do languages have to have a name? The case of Macedonian], in Tabouret-Keller, Andrée (ed.), Le nom des langues. L'enjeu de la nomination des langues (in French), vol. 1, Louvain: Peeters, pp. 167–190, archived from the original on 5 September 2001

- Topolinjska, Z. (1998), "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language", International Journal of the Sociology of Language (131): 1–11, doi:10.1515/ijsl.1998.131.1, S2CID 143257269

- Trudgill, Peter (1992), "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe", International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2 (2): 167–177, doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.1992.tb00031.x

- Voß, C (2018), "Linguistic emancipation within the Serbian mental map: The implementation of the Montenegrin and Macedonian standard languages", Aegean Working Papers in Ethnographic Linguistics, 2 (1): 1–16, doi:10.12681/awpel.20021

External links

- Институт за македонски јазик, "Крсте Петков Мисирков" – Institute for Macedonian language "Krste Misirkov", the main regulatory body of the Macedonian language (in Macedonian)

- Дигитален речник на македонскиот јазик – Online dictionary of the Macedonian language

- Institute for Macedonian language "Krste Misirkov" (2017), Правопис на македонскиот јазик [Orthography of the Macedonian language] (PDF) (2 ed.), Skopje: Kultura AD

- Kramer, Christina; Mitkovska, Liljana (2003), Macedonian: A Course for Beginning and Intermediate Students. (2nd ed.), University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-18804-7

Macedonian travel guide from Wikivoyage

Macedonian travel guide from Wikivoyage The dictionary definition of Macedonian language at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Macedonian language at Wiktionary Macedonian at Wikibooks

Macedonian at Wikibooks