Baltimore–Washington Parkway

| Baltimore–Washington Parkway | ||||

MD 295 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by NPS, MDSHA, Baltimore DOT | ||||

| Length | 32.52 mi[1][2] (52.34 km) | |||

| Existed | 1950–present | |||

| Component highways | ||||

| Tourist routes | ||||

| Restrictions | No trucks south of MD 175[a] | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | ||||

| ||||

| North end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Maryland | |||

| Counties | Prince George's, Anne Arundel, Baltimore, City of Baltimore | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

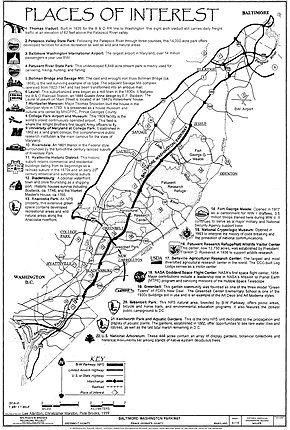

The Baltimore–Washington Parkway (also referred to as the B–W Parkway) is a controlled-access parkway in the U.S. state of Maryland, running southwest from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. The road begins at an interchange with U.S. Route 50 (US 50) near Cheverly in Prince George's County at the Washington, D.C., border, and continues northeast as a parkway maintained by the National Park Service (NPS) to MD 175 near Fort Meade, serving many federal institutions. This portion of the parkway is dedicated to Gladys Noon Spellman, a representative of Maryland's 5th congressional district, and has the unsigned Maryland Route 295 (MD 295) designation. Commercial vehicles, including trucks, are prohibited within this stretch. This section is administered by the NPS's Greenbelt Park unit.[3] After leaving park service boundaries the highway is maintained by the state and signed with the MD 295 designation. This section of the parkway passes near Baltimore–Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport.

Upon entering Baltimore, the Baltimore Department of Transportation takes over maintenance of the road and it continues north to an interchange with Interstate 95 (I-95). Here, the Baltimore–Washington Parkway ends and MD 295 continues north unsigned on Russell Street, which carries the route north into downtown Baltimore. In downtown Baltimore, MD 295 follows Paca Street northbound and Greene Street southbound before ending at US 40.

Plans for a parkway linking Baltimore and Washington date back to Pierre Charles L'Enfant's original layout for Washington, D.C. in the 18th century but did not fully develop until the 1920s. Major reasons surrounding the need for a parkway included high accident rates on adjacent US 1 and defense purposes before World War II. In the mid-1940s, plans for the design of the parkway were finalized and construction began in 1947 for the state-maintained portion and in 1950 for the NPS-maintained segment. The entire parkway opened to traffic in stages between 1950 and 1954.

Following completion of the B–W Parkway, suburban growth took place in both Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. In the 1960s and the 1970s, there were plans to give the segment of the parkway owned by the NPS to the state and make it a part of I-295 and possibly I-95; however, they never came through and the entire road is today designated as MD 295, despite only being signed on the state-maintained portion. Between the 1980s and the 2000s, the NPS portion of the road was modernized. MD 295 is in the process of being widened from four to six lanes, with more widening and a new interchange along this segment planned for the future.

Route description

[edit]NPS segment

[edit]The parkway begins at a large hybrid cloverleaf just outside the Washington, D.C., boundary at Tuxedo, Maryland, that is maintained by the Maryland State Highway Administration.[1] Two other routes cross through the interchange. US 50 west of the interchange heads into Washington, D.C., to become New York Avenue, and to its east becomes the John Hanson Highway, a freeway. MD 201, which begins just south of the interchange at the D.C. line as a continuation of D.C. Route 295, continues north on Kenilworth Avenue, an arterial road that closely parallels to the east of the B–W Parkway for some distance.[1][4]

The portion of the B–W Parkway between the southern terminus and MD 175 is maintained by the National Park Service (NPS). From its southern terminus, the road continues north as a six-lane freeway with the unsigned MD 295 designation, containing brown signs featuring the Clarendon typeface.[1][4] Along this section of the parkway, commercial vehicles such as trucks are prohibited; however, buses and limousines are allowed.[5][1] The parkway heads through wooded surroundings near industrial areas and passes over the Alexandria Extension of CSX's Capital Subdivision railroad line and MD 201, where there is a ramp from southbound MD 201 to the southbound B–W Parkway. It continues northeast, passing near Prince George's Hospital Center, to interchanges with MD 202 (Landover Road) in Cheverly and with MD 450 (Annapolis Road) in Bladensburg and Landover Hills and the former Capital Plaza Mall.[4] Bladensburg itself is a historical waterfront town that consists of houses dating back to the mid-18th century.[6]

It continues north as a four-lane freeway with a wide, tree-filled median, and passes through woodland, skirting residential neighborhoods hidden by the trees. The road has a junction with MD 410 (Riverdale Road) west of New Carrollton.[1][4] This route provides access to the towns of Riverdale Park, which features an 1801 mansion named Riversdale surrounded by suburban development, and Hyattsville, which has buildings dating back to the railroad days of the 1870s and the streetcar and automobile days of the early 20th century.[6] North of here, the route runs near more residences before entering Greenbelt, a suburban garden community built as a model "green town" during the New Deal program in the 1930s, and Greenbelt Park, a park under the jurisdiction of the NPS that has the nearest public camping area to Washington, D.C.[4][6] In the northeastern corner of the park, the Baltimore–Washington Parkway comes to an interchange with I-95 and I-495 (the Capital Beltway).[4] This interchange is the only place where the park service has used green signs compliant with the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD).[1][4]

Just past the Capital Beltway, the route heads into the heart of the city of Greenbelt, having an interchange with MD 193 (Greenbelt Road).[1][4] The headquarters of the U.S. Park Police, which patrol this portion of the parkway, is located off this exit along MD 193.[7] MD 193 provides access to College Park, which is home to the College Park Airport, a 1909 airport where the Wright Brothers taught the U.S. Army how to fly an airplane, and the University of Maryland, College Park, a public educational institution established in 1862.[6] At the northern edge of the town, the route has employee-only access to the Goddard Space Flight Center, the first NASA space flight center opened in 1958 that has contributed to many space missions; from here, the route then enters the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, the largest agricultural research center in the world, owned by the United States Department of Agriculture.[4][6] The parkway's only interchange in the center is at Powder Mill Road, south of Capitol College.[1][4]

Outside the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, the parkway comes to MD 197 (Laurel–Bowie Road) south of Laurel.[1][4] Near this exit of the parkway is the Montpelier Mansion, a Georgian mansion built by Major Thomas Snowden in 1783.[6] Past MD 197, the road passes through the western edge of the Patuxent National Wildlife Research Refuge, a wildlife center established in 1936 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, crossing the Patuxent River into Anne Arundel County.[4][6] Here the parkway continues northeast through dense woodland and comes to the exit for MD 198 (Fort Meade Road) to the east of Laurel, which itself is a suburb that originated in the 1830s as a mill town that contains many historical sites, such as the Laurel Railroad Station (still used today by MARC Train), an 1844 Queen Anne house, and an 1840s millworkers house that is home to the Laurel Museum.[6]

Continuing north, the parkway encounters MD 32 (Savage Road) near Fort Meade.[1][4] MD 32 offers northbound travelers direct access into the fort and to the National Security Agency, while the next interchange, another employee-only access road into Fort Meade, features only a southbound exit and northbound entrance.[4] Fort Meade itself is a military installation opened in 1917 that trained 3.5 million troops during World War II and is still a major fort. To the west of the parkway off MD 32 is the Savage Mill, which was an operating cotton mill from 1822 to 1947 and is currently an antique mall, and the Bollman Truss Railroad Bridge, an 1869 cast and wrought iron bridge along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which is now CSX's Capital Subdivision, line between Baltimore and Washington D.C.[6] After this interchange, the road continues to a cloverleaf interchange with MD 175 (Jessup Road), where NPS maintenance of the parkway comes to an end at the south end of the interchange.[1][4]

MDOT segment

[edit]

Past the MD 175 junction, MD 295 signage begins and the road continues north as a four-lane grade-separated freeway maintained by the Maryland State Highway Administration, where the truck ban ends. This permits trucks to serve into Fort Meade from Baltimore and BWI Airport. This section of the road features standard MUTCD green signage. It heads through wooded areas and comes to a diverging diamond interchange with MD 713F (Arundel Mills Boulevard), which provides access to the Arundel Mills shopping mall and the Live! Casino & Hotel. Past this interchange, MD 295 comes to a cloverleaf interchange with MD 100. Continuing northeast, the route curves to the northwest of Baltimore–Washington International Airport (the largest airport in Maryland), passing near an industrial park before reaching I-195, the main access road to the airport.[1][4][6] Within this interchange, before passing under I-195, the road crosses over Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.[4] I-195 westbound provides access from the Baltimore–Washington Parkway to the Thomas Viaduct, which carries the B&O railroad line over the Patapsco River, and Patapsco Valley State Park, a 14,000-acre (57 km2) state park that preserves the valley of the Patapsco River for recreational purposes.[6]

Still on a northeast track, the route widens to six lanes and intersects West Nursery Road near Linthicum, adjacent to the BWI Hotel District. Past West Nursery Road, the road meets I-695 (the Baltimore Beltway) at a full cloverleaf interchange. Turning north, the route passes under MD 168 (Nursery Road) before crossing the Patapsco River into Baltimore County.[1][4] Upon crossing into Baltimore County, MD 295 reaches a partial interchange with I-895 (Harbor Tunnel Thruway), with access from northbound MD 295 to northbound I-895 and from southbound I-895 to southbound MD 295. Past I-895, the road continues through wooded surrounding with residential developments behind the trees, before entering the city of Baltimore.[1][4]

Baltimore segment

[edit]In Baltimore, MD 295 continues as a limited-access freeway maintained by the Baltimore Department of Transportation, still surrounded by trees with urban residential and industrial neighborhoods nearby, passing under the Curtis Bay Branch of CSX's Baltimore Terminal Subdivision railroad line and coming to an interchange with MD 648 (Annapolis Road) and Waterview Avenue just beyond the city line. Now running due north, the parkway heads over CSX's Hanover Subdivision railroad line before it reaches its northern terminus at I-95. At the I-95 interchange, there are also ramps connecting to Monroe Street. MD 295 downgrades from a limited-access freeway to a six-lane divided city street called Russell Street.[2][4]

MD 295 continues northeast on Russell Street, where it is unsigned for the remainder of the route, through a mix of industrial and commercial areas, heading to the northwest of the Baltimore Greyhound Terminal at Haines Street and the Horseshoe Casino Baltimore. Farther north, the street passes over CSX's Baltimore Terminal Subdivision railroad line before it heads to the west of M&T Bank Stadium, where the Baltimore Ravens of the National Football League play. Past here, the road features an interchange with Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, which becomes I-395 south of Russell Street.[4] After this interchange, MD 295 runs west of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, home to Major League Baseball's Baltimore Orioles, as a four-lane divided street.[4] Immediately after Camden Yards, MD 295 splits into a one-way pair at the intersection with Washington Boulevard with northbound traffic following Eislen Street northeast briefly before heading north on Paca Street and southbound traffic following Greene Street.[2][4] Along the one-way pair, the route intersects many major streets in downtown Baltimore, including Pratt Street, Lombard Street, Baltimore Street, Fayette Street, and Saratoga Street.[4]

Greene Street passes the University of Maryland Medical Center between Lombard Street and Baltimore Street, the Baltimore VA Medical Center between Baltimore Street and Fayette Street, and Westminster Hall and Burying Ground at the corner of Fayette Street. Paca Street passes by the Sonneborn Building north of Pratt Street; the Heiser, Rosenfeld, and Strauss Buildings north of Lombard Street; the historic Paca Street Firehouse and Sanitary Laundry Company Building just north of the intersection with Fayette Street; and Lexington Market at the intersection with Lexington Street.[4] MD 295 reaches its northern terminus at US 40, which follows Mulberry Street eastbound and Franklin Street westbound, in downtown Baltimore. MD 129 continues north from the northern terminus of MD 295, following Paca Street northbound and Pennsylvania Avenue southbound.[2][4]

History

[edit]

Planning

[edit]Plans for a parkway connecting Baltimore and Washington date back to the 1920s as a part of a system that was initially included in Pierre Charles L'Enfant's layout of Washington, D.C., from the 18th century.[8] In 1924, Harry W. Nice, who would later become governor of Maryland, called for the parkway to be constructed.[9]

Early proposals made by the National Capital Park and Planning Commission involved a route that followed US 1 north to MD 198, then east to Fort Meade, but lack of funding led to simpler plans to widen US 1 instead. During the 1930s, the New Deal programs promulgated by President Franklin Roosevelt led to a heightened awareness of the parkway proposals; a 1937 report by the Maryland State Planning Commission increased awareness further.[10] Increasing accident levels on US 1 (which was called one of the deadliest roads in the world at the time) along with awareness of the need to mobilize national defense before World War II provided additional motivation for construction of the parkway.[8][11]

In 1942, the Bureau of Public Roads began the process to start the construction design for the parkway.[12] Federal and state officials commissioned the J. E. Greiner Company to create designs for the parkway, which included a large Y-junction at the southern terminus to connect with New York Avenue and the proposed Anacostia Freeway. Meanwhile, the northern end included a similar wye, with one end running to US 40 (Franklin Street) and the other end crossing the Inner Harbor, but this was modified in 1945 to the current configuration.[13]

Construction

[edit]Construction on the northern portion of the highway began in 1947 by the state of Maryland, while construction on the NPS segment started in 1950.[13] The land for the portion that was to be built by the NPS was acquired at the same time as Greenbelt Park, a park that is under the jurisdiction of the NPS.[14] The state-maintained portion was completed in December 1950 between MD 46 (now I-195) and Hollins Ferry Road at the Baltimore city line and in 1952 from MD 175 to MD 46. The portion of the parkway within the city of Baltimore opened in 1951 while the NPS-maintained portion opened in October 1954.[9] The portion of the road not maintained by the NPS was known as the Baltimore–Washington Expressway while the section maintained by the NPS was called the Baltimore–Washington Parkway.[15]

Post-construction

[edit]Around the time the highway was completed, the federal government began to promote suburbanization by moving several federal agencies out of the capital in order to protect them against nuclear attack.[16] As a result, suburban neighborhoods began to appear in Laurel, Severn, Bowie, and Greenbelt. In addition, the road became a prime commuting route into both Washington and Baltimore, leading to suburban growth that would eventually cause the two distinct cities to merge into one large metropolitan area.[17]

In 1963, the State Roads Commission, the National Park Service, and the Bureau of Public Roads (the predecessor of the Federal Highway Administration) (FHWA) created tentative plans to transfer the NPS segment of the parkway to the state of Maryland, who would then rebuild it to modern freeway standards, with trucks and buses permitted throughout.[18] The plan collapsed due to the state's reluctance to spend the money necessary to reconstruct the parkway, which was one of the most dangerous roads in the NPS road system.[19]

In 1965, the Goddard Space Flight Center constructed the interchange for its employee entrance.[20]

In 1968, the State Roads Commission proposed to the FHWA that the parkway be included in the Interstate Highway System and designated Interstate 295 (in anticipation of the completion of the parallel-running I-95 that occurred in 1971). The designation was granted in 1969, but later withdrawn from all except the current portion signed as I-295 due to lack of funds available to modernize the route.[21] As a result of the withdrawal of the Interstate designation, the parkway remained an unnumbered road south of I-695 while the portion north of there became a part of MD 3 by 1975.[15] Despite this setback, however, plans still existed to widen the parkway to six or even eight lanes. Even though the 1970 Federal Highway Act provided $65 million (equivalent to $394 million in 2023[22]) for this purpose, funding was insufficient to execute these projects. The cancellation of the North Central Freeway and the Northeast Freeway (I-95's routing between New York Avenue and the College Park Interchange) offered a chance for modernization, as plans existed to route I-95 via the B–W Parkway; however, this did not happen and trucks were banned from the parkway again.[23][24]

By 1973, MD 3 was designated along the Baltimore–Washington Expressway between I-695 and Monroe Street in Baltimore.[25] MD 295 was designated along the state-maintained portions of the expressway, replacing the MD 3 designation between I-695 and Monroe Street, by 1981.[26] By the 1990s, the portion of the road known as the Baltimore–Washington Expressway became known as the Baltimore–Washington Parkway.[27]

In the mid-1980s, the National Park Service, along with the Federal Highway Administration, began a reconstruction of the NPS segment to modernize the road, including the improvement of several interchanges.[28] Around 2002, the federal government completed the project with the reconstruction of the MD 197 interchange.[28][29]

In 2004, Maryland Governor Robert L. Ehrlich announced plans to widen portions of MD 295 near Baltimore–Washington International Airport.[30] The MDSHA widened the parkway from two lanes on each side to three lanes on each side from I-195 north to I-695. Construction on the $12.4 million project, which began in late 2008, was completed in late 2011.[31] The widening made use of the median as the extra travel lanes were to be added inside of each carriageway.[32]

The Maryland State Highway Administration closed the southbound ramps of the interchange between the Baltimore–Washington Parkway and Arundel Mills Boulevard starting Monday, May 7, 2012. The closure was for the expedited replacement of the existing dumbbell interchange with Maryland's first diverging diamond interchange. The new interchange was part of $5 million in road upgrades being funded by the Cordish Company ahead of the June 6 opening of the company's Maryland Live! development, which features a casino, near Arundel Mills.[33] The new interchange opened on June 11.[34][35]

Dedications

[edit]In 1983, the NPS-maintained section of the Baltimore–Washington Parkway was named in honor of Gladys Noon Spellman, a congresswoman who represented Maryland's 5th congressional district from January 3, 1975, to January 3, 1981, after a bill introduced into the United States Senate by Senator Paul Sarbanes was signed into law.[36] Gladys Noon Spellman was an educator in Prince George's County and chairperson of the National Mental Health Study Center before becoming the first woman to serve on the county's Board of Commissioners. She suffered a heart attack that ended her congressional career on October 31, 1980, leaving her in a coma until her death on June 19, 1988.[37] On May 9, 1991, the Baltimore–Washington Parkway was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[12][38][39][40]

Incidents

[edit]In 1989, an overpass being built at MD 198 over the B–W Parkway just east of Laurel collapsed during rush hour, injuring fourteen motorists and construction workers. The incident was blamed on faulty scaffolding used to support the uncompleted span.[41] On July 9, 2005, a sinkhole opened beneath the parkway at a construction site, leading to the complete closure of the northbound roadway. The sinkhole was filled with concrete to shore up the roadbed and prevent further collapse; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers attempted to expedite repairs, but the route remained closed until the next day.[42] On August 24, 2007, both directions of the parkway were closed when chunks of concrete fell from the overpass at MD 193 (Greenbelt Road) onto the northbound lanes.[43]

Renovation

[edit]

MD 295 is planned to be widened to six lanes between MD 100 and I-195, and a new interchange is planned to be constructed at Hanover Road. The type of interchange has not yet been decided upon with choices including a diamond interchange, a single-point urban interchange, and a modified cloverleaf interchange. Planning for the $24 million project concluded in 2012.[44]

In September 2017, Governor Larry Hogan announced a plan to widen the Baltimore–Washington Parkway by four lanes, adding express toll lanes to the median, as part of a $9 billion proposal to widen roads in Maryland. The project would be a public-private partnership with private companies responsible for constructing, operating, and maintaining the lanes. As part of the proposal, the portion of the parkway owned by the National Park Service would be transferred to the Maryland Transportation Authority.[45]

In 2019, portions of the National Park Service segment of the Baltimore–Washington Parkway experienced significant pavement deterioration, including several potholes. In March 2019, the speed limit was reduced on the section of the parkway between MD 197 and MD 32 due to poor road conditions.[46] After pressure from Governor Hogan and the state's congressional delegation, the National Park Service announced that emergency pothole repairs would take place from MD 197 to MD 198 on the weekend of March 30–31, 2019, with a complete repave to begin in April 2019, several months ahead of schedule. Repaving of the section between MD 198 and MD 175 occurred later in the year.[47]

Exit list

[edit]All exits are unnumbered.

| County | Location | mi [1][2] | km | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince George's | Tuxedo | 0.00 | 0.00 | Southern terminus | |

| Southbound exit and northbound entrance | |||||

| Bladensburg | 1.65 | 2.66 | |||

| 1.97 | 3.17 | ||||

| Riverdale | 3.63 | 5.84 | |||

| Greenbelt Park | 5.99 | 9.64 | |||

| Greenbelt | 6.36 | 10.24 | |||

| 7.53 | 12.12 | Goddard Space Flight Center (employees only) | |||

| South Laurel | 9.65 | 15.53 | Powder Mill Road – Beltsville | ||

| | 11.51 | 18.52 | |||

| Anne Arundel | | 14.86 | 23.91 | ||

| | 16.61 | 26.73 | Exits 10B-C on MD 32; no southbound access to Canine Road; serves National Cryptologic Museum | ||

| | 17.04 | 27.42 | NSA (restricted entrance) | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | |

| | 18.56 | 29.87 | NPS–MDSHA jurisdictional boundary | ||

| | 18.81 | 30.27 | Access to Jessup MARC Station via MD 175 west; all trucks must exit | ||

| | 20.05 | 32.27 | Arundel Mills Boulevard (MD 713F) | Diverging diamond interchange; access to Live! Casino & Hotel | |

| | 21.31 | 34.30 | Exits 10A-B on MD 100 | ||

| | 24.21 | 38.96 | Exits 2A-B on I-195; former MD 46 | ||

| | 25.42 | 40.91 | West Nursery Road – BWI Hotel District | ||

| Linthicum | 26.59 | 42.79 | Exits 7A-B on I-695; access to Key Bridge | ||

| Baltimore | | 27.66 | 44.51 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |

| | 28.88 | 46.48 | Baltimore city line (MDSHA–Baltimore DOT jurisdictional boundary) | ||

| Baltimore City | 29.89 | 48.10 | Southbound exit and entrance | ||

| Waterview Avenue | Northbound exit and entrance; access to Cherry Hill station | ||||

| 30.11 | 48.46 | Westport | Access via Wenburn/Manokin Streets; access to Westport Light Rail station | ||

| 30.53 | 49.13 | Same-directional access only | |||

| 30.53 | 49.13 | ||||

| 30.53 | 49.13 | Transition between Baltimore–Washington Parkway and Russell Street | |||

| 31.52 | 50.73 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 32.45 | 52.22 | ||||

| 32.52 | 52.34 | Northern terminus | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Anne Arundel County, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Prince George's County, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Baltimore County, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Baltimore, Maryland

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Highway Information Services Division (December 31, 2013). Highway Location Reference. Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- Prince George's County (PDF).

- Anne Arundel County (PDF).

- Baltimore County (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e Highway Information Services Division (December 31, 2005). Highway Location Reference. Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- Baltimore City (PDF).[dead link]

- ^ "Baltimore–Washington Parkway Management". National Park Service.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Overview of Maryland Route 295" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ "Baltimore–Washington Parkway: Fees & Reservations". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Map of the Baltimore–Washington Parkway". National Park Service. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ^ "Baltimore–Washington Parkway: United States Park Police". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Parkways of the National Capital Region, 1913 - 1965" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "Major transportation milestones in the Baltimore region since 1940" (PDF). Baltimore Metropolitan Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ McBee, Avery (October 11, 1936). "Baltimore–Washington Parkway: A New Link Is Projected with the Nation's Capital". The Baltimore Sun (Sunday Sun Magazine). p. 3.

- ^ Duensing, Dawn (2000). "Baltimore–Washington Parkway" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 1. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ a b "Baltimore–Washington Parkway". Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Baltimore–Washington Parkway". Baltimore Magazine. August 1950.[page needed]

- ^ "Greenbelt Park". Potomac Appalachian Trail Club. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Exxon; General Drafting (1975). Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia (Map). Exxon.[full citation needed]

- ^ "B.2 History of Suburbanization in Maryland" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "B.3.3 Modern Period (1930-1960)" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "State to Get DC Parkway". Baltimore News-Post. August 16, 1963.[page needed]

- ^ "State Is Found Unwilling to Take Over the Parkway". The Baltimore Sun. April 20, 1969. p. 20.

- ^ "Environmental Statement for Goddard Space Flight Center". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. March 17, 1971. p. 16. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ Ayres, Horace (August 22, 1969). "Parkway Won't Become Part of Interstate". The Evening Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. p. C4.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Dilts, James D. (December 9, 1974). "Battle Brews on Widening of Baltimore-DC Road". The Baltimore Sun. p. C1.

- ^ Rascovar, Barry C. (July 5, 1976). "Parkway Plans Narrowed". The Baltimore Sun. p. C1.

- ^ Exxon; General Drafting (1973). Baltimore and vicinity (Map). Exxon.[full citation needed]

- ^ Exxon; General Drafting (1981). Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia (Map). Exxon.[full citation needed]

- ^ Rand McNally (1996). United States-Canada-Mexico Road Atlas (Map). Chicago: Rand McNally.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b "Reconstruction on Final Segment Of B-W Parkway to Begin Today". United States Department of Transportation. July 6, 1999. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Statement of Mary Peters". United States Department of Transportation. August 8, 2002. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Kosmetatos, Sofia (October 29, 2004). "Counties get details of state plans for divvying up new funds for". Daily Record.[page needed]

- ^ "Lanes To Be Added To Baltimore–Washington Parkway". WJZ-TV. October 23, 2008.

- ^ "MD 0295 Baltimore/Washington Parkway RI- I-695 to I-195". Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ Fuller, Nicole (May 1, 2012). "Temporary Road Closures Planned Around Arundel Mills". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ Wild, Whitney (June 11, 2012). "Interchange opens at 295 and Arundel Mills Boulevard". WJLA-TV. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Drivers Navigate Maryland's First Diverging Diamond Interchange". Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ "S.680 A bill entitled the "Gladys Noon Spellman Parkway."". GovTrack. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "Baltimore–Washington Parkway: History & Culture". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Leach, Sara Amy (March 28, 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Baltimore–Washington Parkway". National Park Service. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Leach, Sara Amy (March 28, 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Baltimore–Washington Parkway". National Park Service. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Leach, Sara Amy (April 1, 1988). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Baltimore–Washington Parkway". National Park Service. Retrieved September 13, 2018. with photos

- ^ Duggan, Paul and Veronica T. Jennings (September 1, 1989). "Overpass Collapses on B-W Parkway, Injuring Fourteen". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Rucker, Philip and Nick Anderson (July 9, 2005). "Rains Open B-W Parkway Sinkhole". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- ^ Harris, Hamil R. (August 25, 2007). "Falling Concrete Shuts Down B-W Parkway". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "MD 0295 Baltimore/Washington Parkway MD 100 to I-695 and Hanover Road". Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Hogan proposes $9B plan to add new lanes to Beltway, 270 and BW Parkway". Washington, DC: WTOP-FM. September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (March 5, 2019). "The potholes are so bad on a stretch of the Baltimore-Washington Parkway that the speed limit was lowered". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (March 27, 2019). "National Park Service to begin emergency repairs on Baltimore-Washington Parkway amid pressure from lawmakers". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

External links

[edit]- MD 295 at MDRoads.com

- MD 295 - Baltimore-Washington Parkway at AARoads.com

- Maryland Roads - MD 295, Balto-Wash Pkwy.

- National Park Service - Baltimore–Washington Parkway

- Steve Anderson's DCroads.net: Baltimore–Washington Parkway (MD 295)

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MD-129, "Baltimore–Washington Parkway, Greenbelt vicinity, Prince George's County, MD", 49 photos, 2 color transparencies, 10 measured drawings, 146 data pages, 5 photo caption pages

- United States federal parkways

- Roads in Prince George's County, Maryland

- Roads in Anne Arundel County, Maryland

- Roads in Baltimore County, Maryland

- Roads in Baltimore

- Roads on the National Register of Historic Places in Maryland

- Limited-access roads in Maryland

- Freeways in the United States

- National Park Service areas in Maryland

- National Capital Parks-East

- Historic American Engineering Record in Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places in Annapolis, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places in Baltimore County, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places in Prince George's County, Maryland

- Parks on the National Register of Historic Places in Maryland